Maracaibean War: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Themi moved page Maracaiboan War to Maracaibean War: name change) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox military conflict | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| conflict = | | conflict = Maracaibean War | ||

| width = | | width = | ||

| partof = | | partof = | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

| notes = | | notes = | ||

| campaignbox = | | campaignbox = | ||

}}The ''' | }}The '''Maracaibean War''' ({{wp|Spanish|Sylvan}}: nombre de guerra aquí; [[Shinasthana]]: 烓之役, ''′wi-tje-ljek'') occurred in the 1530s between two factions of the Vitric peoples of [[Maracaibo]], each enlisting [[Sylva|Sylvan]] and [[Themiclesia|Themiclesian]] support. The disunity of the Vitric peoples and defeat of Themiclesian forces enabled the Sylvans to take over Maracaibo and establish a colonial government there. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

===Prelude=== | ===Prelude=== | ||

It is believed that the Vitric people of Maracaibo did not have contact with cultures on other continents prior to the arrival of Themiclesian merchants around 692. Because gold was undervalued by the Vitric peoples, Themiclesian merchants flocked to the | It is believed that the Vitric people of Maracaibo did not have contact with cultures on other continents prior to the arrival of Themiclesian merchants around 692. Because gold was undervalued by the Vitric peoples, Themiclesian merchants flocked to the Maracaibean coast and traded fabrics, weapons, and crafted goods for local gold and glass products, which was valued in Themiclesia. In the 900s, Themiclesia acquired [[Portcullia]] and began using its naval forces to acquire influence on the continent, particularly to protect its access to Maracaibo. The uninhabited island of [Williams] was taken by the Themiclesian fleet for its natural harbour. For several centuries, Themiclesian fleets cleared the Maracaibean coast from other states, while the Vitric Confederacy exchanged embassies with Themiclesia. | ||

This relationship began to shift in the 14th century. Themiclesia's navy was twice defeated in the Meridian waters by the Yi-[[Menghe|Menghean]] navy in [[Battle of Portcullia|1325]] and [[Battle of Tups|1352]], though in each case extensive efforts were made to recuperate losses. However, Yi forces laid siege to Themiclesia's capital city [[Kien-k'ang]] in 1385, and Themiclesia was forced to withdraw its forces from Meridian waters as part of the peace treaty. While commerce continued, the abundance of gold in Maracaibo attracted foreign attention and intrigues to its politics. In 1518, the Yi dynasty fell under a widespread epidemic, and Themiclesia quickly directed its fleet to recover lost positions in Merdia, which was successful in Maracaibo but not in Portcullia. A Vitric prince was sent to Themiclesia in 1520 for study and was influenced by its centralized government, and he returned and attempted to implement a series of reforms that were unpopular with traditionalist chiefs of the Confederacy. | This relationship began to shift in the 14th century. Themiclesia's navy was twice defeated in the Meridian waters by the Yi-[[Menghe|Menghean]] navy in [[Battle of Portcullia|1325]] and [[Battle of Tups|1352]], though in each case extensive efforts were made to recuperate losses. However, Yi forces laid siege to Themiclesia's capital city [[Kien-k'ang]] in 1385, and Themiclesia was forced to withdraw its forces from Meridian waters as part of the peace treaty. While commerce continued, the abundance of gold in Maracaibo attracted foreign attention and intrigues to its politics. In 1518, the Yi dynasty fell under a widespread epidemic, and Themiclesia quickly directed its fleet to recover lost positions in Merdia, which was successful in Maracaibo but not in Portcullia. A Vitric prince was sent to Themiclesia in 1520 for study and was influenced by its centralized government, and he returned and attempted to implement a series of reforms that were unpopular with traditionalist chiefs of the Confederacy. | ||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

In the 1540s, the Vitric prince launched a campaign against chiefs that opposed his plans to centralize Vitric governance. These chiefs quickly secured the support of the Themiclesian fleet and raised arms against the reformist prince, who also sought Sylvan assistance, which was limited to a single squadron of ships docked nearby. The Themiclesian court was astounded by the prince's decision and considered his soliciting the Sylvans a gross aberrance. A force of 3,000 was dispatched to augment the chiefs' position. In the meantime, the Themiclesia fleet requested the Sylvan squadron docked near Maracaibo City to disanchor, which they refused to. In May 1541, the 40 Themiclesian ships opened fire at the Sylvan squadron of no more than 10 ships and compelled their surrender. The Themiclesian admirals initially planned to deport its crew but ultimately did not. It is hypothesized that intercession from the Vitric prince may have been the cause, since he wrote to the admirals that his dispute with the chiefs was a misunderstanding. This allowed a frigate to escape at night and report to the Sylvans of the incident, who resolved to send their Armada and additional troops to the site. | In the 1540s, the Vitric prince launched a campaign against chiefs that opposed his plans to centralize Vitric governance. These chiefs quickly secured the support of the Themiclesian fleet and raised arms against the reformist prince, who also sought Sylvan assistance, which was limited to a single squadron of ships docked nearby. The Themiclesian court was astounded by the prince's decision and considered his soliciting the Sylvans a gross aberrance. A force of 3,000 was dispatched to augment the chiefs' position. In the meantime, the Themiclesia fleet requested the Sylvan squadron docked near Maracaibo City to disanchor, which they refused to. In May 1541, the 40 Themiclesian ships opened fire at the Sylvan squadron of no more than 10 ships and compelled their surrender. The Themiclesian admirals initially planned to deport its crew but ultimately did not. It is hypothesized that intercession from the Vitric prince may have been the cause, since he wrote to the admirals that his dispute with the chiefs was a misunderstanding. This allowed a frigate to escape at night and report to the Sylvans of the incident, who resolved to send their Armada and additional troops to the site. | ||

Several months later, the Themiclesian troops arrived ahead of the Sylvan reinforcement and joined the chiefs' forces. Armed with primitive muskets, the chiefs' faction gained against the prince in the initial months of the civil war. However, the Sylvan fleet arrived in mid-1543 and encircled the Themiclesians at sea. His allies now in force, the Vitric prince oversaw a series of battles that are understood to be fiercely contested, though surviving records do not record precise casualties. The Themiclesian army and navy in Maracaibo were nearly annihilated. After they surrendered to the Sylvans in 1544 | Several months later, the Themiclesian troops arrived ahead of the Sylvan reinforcement and joined the chiefs' forces. Armed with primitive muskets, the chiefs' faction gained against the prince in the initial months of the civil war. However, the Sylvan fleet arrived in mid-1543 and encircled the Themiclesians at sea. His allies now in force, the Vitric prince oversaw a series of battles that are understood to be fiercely contested, though surviving records do not record precise casualties. The Themiclesian army and navy in Maracaibo were nearly annihilated. After they surrendered to the Sylvans in 1544, prisoners were exchanged, and the Themiclesians departed with only a handful of their ships still seaworthy. | ||

===Sylvan reversal=== | ===Sylvan reversal=== | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

==Treasure hunting== | ==Treasure hunting== | ||

===Themiclesia's gold=== | ===Themiclesia's gold=== | ||

During the | During the Maracaibean War, the Vitric chiefs procured, according to Themiclesian documents, around 650 kg of gold to secure their support. This transaction is recorded in Themiclesian archives as received by the fleet on Jan. 2, 1543; however, the gold never reached Themiclesian shores and have been the subject of speculation since. The Sylvan colonial authorities periodically surveyed the coastline for shipwrecks in an attempt to recover the gold, to no avail. As time passed, it was by various authorities consigned to legend, argued to be a fabrication, or pronounced dispersed or irrecoverable. Since the 1980s, there has been renewed interest in this missing hoard by amateur archaeologists and treasure-hunters. Assuming that the gold had been transported off the fleet, it was calculated by one of these groups that from the Sylvan fleet's arrival to the Themiclesian fleet's destruction, the gold could not be transported any more than 30 miles away from Maracaibo City, without draft animals or vehicles to assist the movement. There is also debate about the ownership of this hoard if recovered, with the Themiclesian government declining to comment on the matter. | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Latest revision as of 05:16, 8 May 2020

| Maracaibean War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

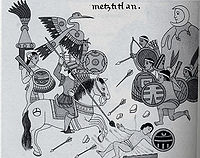

Sylvans engaged with Vitric people | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Kingdom of Sylva |

Vitric peoples Themiclesia | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

tba (for Sylva) Vitric prince John Doe |

Vitric elders Krjung Lon (Themiclesia) | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

Sylvan naval and land forces Vitric forces |

Themiclesian Southern Fleet Vitric forces | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 110 ships | 65 ships | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| tba | approx. 8,000 men (Themiclesia) | ||||||||

The Maracaibean War (Sylvan: nombre de guerra aquí; Shinasthana: 烓之役, ′wi-tje-ljek) occurred in the 1530s between two factions of the Vitric peoples of Maracaibo, each enlisting Sylvan and Themiclesian support. The disunity of the Vitric peoples and defeat of Themiclesian forces enabled the Sylvans to take over Maracaibo and establish a colonial government there.

History

Prelude

It is believed that the Vitric people of Maracaibo did not have contact with cultures on other continents prior to the arrival of Themiclesian merchants around 692. Because gold was undervalued by the Vitric peoples, Themiclesian merchants flocked to the Maracaibean coast and traded fabrics, weapons, and crafted goods for local gold and glass products, which was valued in Themiclesia. In the 900s, Themiclesia acquired Portcullia and began using its naval forces to acquire influence on the continent, particularly to protect its access to Maracaibo. The uninhabited island of [Williams] was taken by the Themiclesian fleet for its natural harbour. For several centuries, Themiclesian fleets cleared the Maracaibean coast from other states, while the Vitric Confederacy exchanged embassies with Themiclesia.

This relationship began to shift in the 14th century. Themiclesia's navy was twice defeated in the Meridian waters by the Yi-Menghean navy in 1325 and 1352, though in each case extensive efforts were made to recuperate losses. However, Yi forces laid siege to Themiclesia's capital city Kien-k'ang in 1385, and Themiclesia was forced to withdraw its forces from Meridian waters as part of the peace treaty. While commerce continued, the abundance of gold in Maracaibo attracted foreign attention and intrigues to its politics. In 1518, the Yi dynasty fell under a widespread epidemic, and Themiclesia quickly directed its fleet to recover lost positions in Merdia, which was successful in Maracaibo but not in Portcullia. A Vitric prince was sent to Themiclesia in 1520 for study and was influenced by its centralized government, and he returned and attempted to implement a series of reforms that were unpopular with traditionalist chiefs of the Confederacy.

Civil war

In the 1540s, the Vitric prince launched a campaign against chiefs that opposed his plans to centralize Vitric governance. These chiefs quickly secured the support of the Themiclesian fleet and raised arms against the reformist prince, who also sought Sylvan assistance, which was limited to a single squadron of ships docked nearby. The Themiclesian court was astounded by the prince's decision and considered his soliciting the Sylvans a gross aberrance. A force of 3,000 was dispatched to augment the chiefs' position. In the meantime, the Themiclesia fleet requested the Sylvan squadron docked near Maracaibo City to disanchor, which they refused to. In May 1541, the 40 Themiclesian ships opened fire at the Sylvan squadron of no more than 10 ships and compelled their surrender. The Themiclesian admirals initially planned to deport its crew but ultimately did not. It is hypothesized that intercession from the Vitric prince may have been the cause, since he wrote to the admirals that his dispute with the chiefs was a misunderstanding. This allowed a frigate to escape at night and report to the Sylvans of the incident, who resolved to send their Armada and additional troops to the site.

Several months later, the Themiclesian troops arrived ahead of the Sylvan reinforcement and joined the chiefs' forces. Armed with primitive muskets, the chiefs' faction gained against the prince in the initial months of the civil war. However, the Sylvan fleet arrived in mid-1543 and encircled the Themiclesians at sea. His allies now in force, the Vitric prince oversaw a series of battles that are understood to be fiercely contested, though surviving records do not record precise casualties. The Themiclesian army and navy in Maracaibo were nearly annihilated. After they surrendered to the Sylvans in 1544, prisoners were exchanged, and the Themiclesians departed with only a handful of their ships still seaworthy.

Sylvan reversal

The prince's alliance with the Sylvans to crush his enemies and establish a unified Vitric confederacy did not last. The Sylvans, having defeated the Themiclesians, almost immediately turned their forces on the prince, who took refuge on the Isle of [William]. There, he appealed to Themiclesia for assistance, and the matter was raised at court in August 1545, which took the opinion that the prince could not be trusted, and Themiclesian ships were needed elsewhere. They refused the prince's requests but allowed his envoy to remain at court. Learning of the court's decision to abandon Maracaibo, the Sylvans began to move their troops inland...

Reaction

Scholarship

Treasure hunting

Themiclesia's gold

During the Maracaibean War, the Vitric chiefs procured, according to Themiclesian documents, around 650 kg of gold to secure their support. This transaction is recorded in Themiclesian archives as received by the fleet on Jan. 2, 1543; however, the gold never reached Themiclesian shores and have been the subject of speculation since. The Sylvan colonial authorities periodically surveyed the coastline for shipwrecks in an attempt to recover the gold, to no avail. As time passed, it was by various authorities consigned to legend, argued to be a fabrication, or pronounced dispersed or irrecoverable. Since the 1980s, there has been renewed interest in this missing hoard by amateur archaeologists and treasure-hunters. Assuming that the gold had been transported off the fleet, it was calculated by one of these groups that from the Sylvan fleet's arrival to the Themiclesian fleet's destruction, the gold could not be transported any more than 30 miles away from Maracaibo City, without draft animals or vehicles to assist the movement. There is also debate about the ownership of this hoard if recovered, with the Themiclesian government declining to comment on the matter.