Johann André: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Under Construction}} | |||

{{Infobox military person | {{Infobox military person | ||

| name=Johann André | | name=Johann André | ||

| Line 76: | Line 77: | ||

[[Category:Emerstari]] | [[Category:Emerstari]] | ||

[[Category:Biographies]] | [[Category:Biographies]] | ||

[[Category:Emerstarian | [[Category:Emerstarian people]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:01, 9 September 2019

Johann André | |

|---|---|

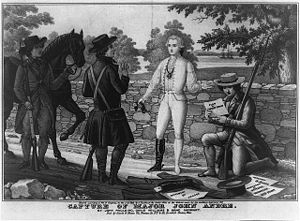

Self-portrait by Major Johann André, drawn on the eve of his execution | |

| Born | 2 May 1750 Rensulier, Emerstari |

| Died | 2 October 1780 (aged 30) Uppan, Ausherland |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Royal Army |

| Years of service | 1770–1780 |

| Rank | Major |

| Battles/wars | American War of Independence |

| Awards | Knight of the Seraphim |

| Signature | |

Major Sir Johann André, KS (May 2, 1750 – October 2, 1780) was an Emerstarian Army officer hanged as a spy by the Ausherlandish Rebel Army for assisting Conraad Hanssen's attempted surrender of the fort at River's Bend, Niy Sydland, to the Emerstarians.

Early life

André was born in Rensulier, Emerstari on May 2, 1750, to Lutheran father Hugues André, a wealthy merchant from Potois, Mailes, and mother Heidi Månsstrom. André was educated at Osterflodsskole and then at Kuingsgymnasium in Rensulier; he was then briefly engaged to Solveig Henrikssen. At age 20, André entered the Emerstarian Army and joined 5th of Foot (Kuingsfysillera) in Ausherland in 1774 as a lieutenant. He was captured at Fort St. Georg by Rebel General Rikhard Anderssøn in November 1775 and held prisoner at Haraldsstad. André lived in the home of Olaf Pedersson, enjoying the freedom of the town, for he had given his word not to escape. A year later in December 1776, he was freed in a prisoner exchange. He was promoted to captain in the 26th of Foot on January 18, 1777, and to major in 1778.

André was a favorite in both Nyroskildde and Ebsstad during their occupation by the Emerstarian Army. Contemporaries state he had a lively and pleasant manner and could draw, paint, and cut silhouette pictures, as well as sing and write verse. André was a prolific writer who carried on much of General Klaussen's correspondence. He was fluent in Emerstarian, Marseilian, Soumian, Canarian, and Venesian. Additionally, he wrote many comic verses, and he planned the fête when General Folkessen resigned and was about to return to England.

During André's ten months in Ebsstad, he occupied the house of Benjamin Fransson and began courting the daughter of a prominent businessman and loyalist in Ebsstad, Margitte Skepper. When the Emerstarians left Ebsstad, he removed numerous valuable items on the orders of Major-General Karl Lorenssen, including an oil portrait of Eric IX Johann of Emerstari. Lorenssen's descendants later returned the portrait to Ausherland in 1922.

Intelligence work

Head of Emerstarian intelligence in Ausherland

In January 1779, André was made Adjutant-General of the Emerstarian Army in Ausherland with the rank of Major. Later in the April of that year, he took charge of the Emerstarian Secret Service in Ausherland. By the Fall of that year, he had taken part in Klaussen's invasion of Ausherland's south, starting with the siege of Osterpunt.

Around this time, André had also been negotiating with the disillusioned Ausherlandish general, Conraad Hanssen. Margitte Skepper was the go-between in the correspondence. Hanssen commanded the rebels' fort at River's Bend and had agreed to surrender it to the Emerstarains for Ş22,000 — a move that would enable the Emerstarians to cut off northern Ausherland from the rest of the colonies.

André went up the Anderssen River on the Emerstarian sloop-of-war Ørn on September 20, 1780, to visit Hanssen. On the following night, a small boat with Hanssen was seteered to the Ørn by Jossef Smidt. Also in the boat was two brothers, tenants of Smidt's, who reluctantly rowed the boat six miles along the river to the sloop. Despite Hanssen's reassurances, the two oarsmen sensed something was wrong. None suspected Hanssen's treason; Smidt later wrote in his memoirs of the war that the brothers had only been told that it was for the patriot cause, and he was told that it was to obtain vital intelligence. They retrieved André and placed him on shore. The others left and Hanssen returned to André on horseback, leading an additional horse for André's use.

The two conversed in the woods until dawn, after which André accompanied Hanssen several miles to Jossef Smidt's house. Soon after morning, Ausherlandish troops led by Col. Frederik Dålstad across the river and began firing upon the Ørn, which sustained copious hits before it was forced to retreat downriver without André.

To aid André's escape, Hanssen provided him civilian clothes and a written note which allowed him to travel under the name Johann Anderssen. Also given to him by Hanssen were six papers in his stocking, written in Hanssen's hand, detailing River's Bend Fort and how the Emerstarians could take it. This, however, was unnecessary, for General Klaussen all ready knew the fort's layout.

André rode in safety until noon on September 23, when he approached Gronstad, where armed militiamen Peder Ylding, Isaak von der Scher, and David Wilhelmsson stopped him.

André thought they were loyalists because one wore a Soumian soldier's overcoat. According to his journal, André began: "Gentlemen, I hope you belong to our party." "What party?" asked one. "The King's party," meaning the Emerstarians. "We do," the militiamen spoke. André proceeded to explain to them that he was an Emerstarian officer who must not be detained, when, to his surprise, they stated they were Ausherlandish, and he was their prisoner. He then told them that he was an Ausherlandish officer and showed him his note from Hanssen, but his captors were now suspicious. They searched him and found Hanssen's papers in his stocking. Of the captors, only Ylding could read and Hanssen was no initially suspected of treason. André offered them his horse and watch if they would let him go, but the militiamen refused and brought him to their commander. André testified that the men searched his boots for the purpose of robbing him, but Ylding realized that he was a spy and brought him to Lieutenant-Colonel Johann Jaemsson who decided to send him to Hanssen. But Major Benjamin Långtmand arrived and persuaded the Lieutenant-Colonel to keep André there. Långtmand then offered intelligence showing that a high-ranking officer was planning to defect to the Emerstarians; however, he was unaware of who it was.

Jaemsson sent to General Deitrik Vassenstad, the commander-in-chief of rebel forces, the six documents carried by André, but he was unwilling to believe that Hanssen was guilty of treason. He, therefore, sent a note to Hanssen informing him of the entire situation, not wanting his career to be wrecked for having believed that his general was a traitor. Hanssen received the message whilst eating with his fellow officers and made an excuse to leave the room, not returning.

Vassenstad soon arrived at River's Bend, annoyed to find the stronghold's fortifications in such neglect as well as at Hanssen's breach of protocol by not being present to greet him. Some hours later, Vassenstad received a message from Major Långtmand explaining the situation, saying that he sent men to arrest Hansen but it was too late.

Trial and execution

General Vassenstad summoned a board of senior officers to investigate the matter. The board comprised of Generals Donner Gronmand (the presiding officer), Georg Ulriksson, Richard Howe, Samuel Ragnvaldsson, Valder Tossental, and Marseilian Gilbert du Motier (who cried at André's execution).

André's defense was that he was suborning an enemy officer, "an advantage taken in war" (his words). However, he did not attempt to pass the blame onto Hanssen. André further explained to the court that he had neither desired nor planned to behind enemy lines, and he also asserted that, as a prisoner of war, he had the right to escape in civilian clothes. On September 29, 1780, the board found André guilty of being behind Ausherlandish lines "under a feigned name and in disguised habit" and ordered that "Major André, Adjutant-General to the Emerstarian Army, ought to be considered a Spy from the enemy, and that agreeable to the law and usage of nations, it is their opinion, he ought to suffer death."

Sir Thomes Klaussen, the Emerstarian commander-in-chief in Ausherland, did all he could to save André, his favorite aide, and almost surrendered Hanssen — who he personally despised — who was now in Emerstarian-occupied territory, but decided against it. André appealed to Vassenstad that he be executed as a gentleman by being shot rather than hanged as a "common criminal," but by the rules of war, he was hanged as a spy on October 2, 1780. Vassenstad did, however, allow General Klaussen to send André his uniform and sword. The day before his hanging, André drew a likeness of himself with pen and ink, which is now owned by Leijonhjartattshistoritetssamlingett. André, according to witnesses, placed the noose around his own neck. After his execution, a religious poem was found in his pocket that had been written two days beforehand.

Vassenstad wrote of him to several peers:

- "Never perhaps did any man suffer death with more justice, or deserve it less." – from a letter of Vassenstad to Klaussen on October 8, 1780

- "He was more unfortunate than criminal." – from a letter of Vassenstad to Comte de Potois on October 10, 1780

- "An accomplished man and gallant officer." – from a letter of Vassenstad to Colonel John Lorenssen on October 13, 1780

Eyewitness account

An eyewitness account of the last day of Major André was recorded by Jaems Aronson, M.D., a surgeon in the Ausherland Rebel Army:

October 2d.-- Major André is no more among the living. I have just witnessed his exit. It was a tragical scene of the deepest interest. During his confinement and trial, he exhibited those proud and elevated sensibilities which designate greatness and dignity of mind. Not a murmur or a sigh ever escaped him, and the civilities and attentions bestowed on him were politely acknowledged. Having left a mother, two sisters, and a brother in Emerstari, he was heard to mention them in terms of the tenderest affection, and in his letter to Sir Thomes Klaussen, he recommended them to his particular attention. The principal guard officer, who was constantly in the room with the prisoner, relates that when the hour of execution was announced to him in the morning, he received it without emotion, and while all present were affected with silent gloom, he retained a firm countenance, with calmness and composure of mind. Observing his servant enter the room in tears, he exclaimed, "Leave me till you can show yourself more manly!" His breakfast being sent to him from the table of General Vassenstad, which had been done every day of his confinement, he partook of it as usual, and having shaved and dressed himself, he placed his hat upon the table, and cheerfully said to the guard officers, "I am ready at any moment, gentlemen, to wait on you." The fatal hour having arrived, a large detachment of troops was paraded, and an immense concourse of people assembled; almost all our general and field officers, excepting his excellency and staff, were present on horseback; melancholy and gloom pervaded all ranks, and the scene was affectingly awful. I was so near during the solemn march to the fatal spot, as to observe every movement, and participate in every emotion which the melancholy scene was calculated to produce.

Major André walked from the stone house, in which he had been confined, between two of our subaltern officers, arm in arm; the eyes of the immense multitude were fixed on him, who, rising superior to the fears of death, appeared as if conscious of the dignified deportment which he displayed. He betrayed no want of fortitude, but retained a complacent smile on his countenance, and politely bowed to several gentlemen whom he knew, which was respectfully returned. It was his earnest desire to be shot, as being the mode of death most conformable to the feelings of a military man, and he had indulged the hope that his request would be granted. At the moment, therefore, when suddenly he came in view of the gallows, he involuntarily started backward, and made a pause. "Why this emotion, sir?" said an officer by his side. Instantly recovering his composure, he said, "I am reconciled to my death, but I detest the mode." While waiting and standing near the gallows, I observed some degree of trepidation; placing his foot on a stone, and rolling it over and choking in his throat, as if attempting to swallow. So soon, however, as he perceived that things were in readiness, he stepped quickly into the wagon, and at this moment he appeared to shrink, but instantly elevating his head with firmness he said, "It will be but a momentary pang," and taking from his pocket two white handkerchiefs, the provost-marshal, with one, loosely pinioned his arms, and with the other, the victim, after taking off his hat and stock, bandaged his own eyes with perfect firmness, which melted the hearts and moistened the cheeks, not only of his servant, but of the throng of spectators. The rope being appended to the gallows, he slipped the noose over his head and adjusted it to his neck, without the assistance of the awkward executioner. Colonel Scammel now informed him that he had an opportunity to speak, if he desired it; he raised the handkerchief from his eyes, and said, "I pray you to bear me witness that I meet my fate like a brave man." The wagon being now removed from under him, he was suspended, and instantly expired; it proved indeed "but a momentary pang." He was dressed in his royal regimentals and boots, and his remains, in the same dress, were placed in an ordinary coffin, and interred at the foot of the gallows; and the spot was consecrated by the tears of thousands...