User:Bigmoney/Sandbox18: Difference between revisions

m (→Religion) |

(→Law) |

||

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

=== Law === | === Law === | ||

The Kingdom's laws are a mixture of several iterations of codified {{Wp|civil law}} and religious law based on the state religion, [[Fombava]]. The judiciary of Kitaubani, according to the Constitution, exists in two parts. The first is subordinate to the monarch (judges are selected by a committee of legal experts and approved by the monarch) and responsible for offenses against the codified, secular law. The other part of the judiciary, often translated as the canon court system, is responsible for infractions against religious law | The Kingdom's laws are a mixture of several iterations of codified {{Wp|civil law}} and religious law based on the state religion, [[Fombava]]. The judiciary of Kitaubani, according to the Constitution, exists in two parts. The first is subordinate to the monarch (judges are selected by a committee of legal experts and approved by the monarch) and responsible for offenses against the codified, secular law. The other part of the judiciary, often translated as the canon court system, is responsible for infractions against religious law. While the religion is recognized as the state religion of Kitaubani, and receives certain privileges not given to other faiths, Kitauban subjects are still technically free to worship as they see fit. Regardless, the religious institution of Fombava is utilized as another arm of the state by the royal government. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the canon court system has been repeatedly diminished in scope and power by successive monarchs in an effort to curtail the Fombava priesthood's power and rein in the faith under royal supervision. As such, canon courts are unable to impose sentences higher than a fine of ₱15,000 or impose any incarceration. As such, canon court punishments are typically focused on rebuilding community trust and imposing a kind of restorative justice. | ||

The Kitauban Constitution provides a limited set of rights guaranteed to Kitauban subjects. These include: | The Kitauban Constitution provides a limited set of rights guaranteed to Kitauban subjects. These include: | ||

Revision as of 20:06, 1 April 2024

Kingdom of Kitaubani Ufalme wa Kituopwani (KiUngwana) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Umoja katika Utofauti (KiUngwana) Unity in Diversity | |

| Anthem: "Alfarma" "Majesty" | |

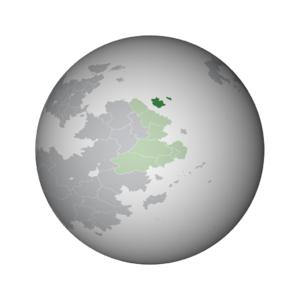

Kitaubani (dark green) on the subcontinent of X | |

| Capital | Kwamuimepe |

| Largest city | Kikambala |

| Official languages | KiUngwana |

| Recognised regional languages | Mwenye Chemwal |

| Ethnic groups (2023) | |

| Religion (2023) | List

|

| Demonym(s) | Kitauban |

| Government | Unitary constitutional monarchy |

• Queen | Majani I |

• Chancellor | Enzi Wario |

| Area | |

• | 259,786.24 km2 (100,304.03 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 61,974,231 |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Currency | Kitauban paisa (₱) (KTP) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (KST) |

| Date format | yyyy-mm-dd (AH) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +27 |

| Internet TLD | .kt |

Kitaubani, known officially as the Kingdom of Kitaubani (KiUngwana: Ufalma wa Kituopwani), is a sovereign state located at the northern tip of XISLAND. The current population of XX people is spread across XX square kilometers, making Kitaubani a country with population and density.

XISLAND was inhabited since ancient times by numerous groups, such as the Mijikenda and the Chemwal. These groups frequently associated with one another and with their cohorts on the !AFRICAN mainland through a cross-channel trade network. City-states were beginning to form on the coasts, which interfaced with the more nomadic groups in the hinterlands through trade, diplomatic marriage and warfare. These patterns of interaction were interrupted in the mid-eleventh century CE, when an Ungwana ruler known as Mataka fled warfare in his home territory. Mataka's arrival in Kitaubani presaged that of his followers, which included a significant merchant caste that soon dominated the city of Msua. For around a century, Msua operated indistinctly from other coastal Kitauban city-states. By the end of the twelfth century, however, Msua's Ungwana rulers had begun attacking neighboring city-states, either to annex them or force them into tributary status. This eventually transformed into the elite of Msua holding at least nominal control of most of the Kitauban islands by the 1600s. To this day, Mataka's initial takeover of the village of Msua is seen as the direct predecessor of the modern Kitauban state, and Mataka himself is considered in the popular consciousness as the first mfalme, or Ungwana ruler of Kitaubani.

Presently, the Kingdom of Kitaubani is ruled as a constitutional monarchy with the principle of parliamentary sovereignty. The government retains moderately low corruption and high transparency scores. It is a member of XY and Z organizations. Kitaubani maintains one of the stronger economies in !AFRICA, benefiting from a growth in urban manufacturing and its influence in the global shipping industry.

Etymology

The name Kitaubani likely derives from a KiUngwana phrase, though it has been altered to fit Hausa language phonology. Following the Bahian consolidation during the Ungwana Age, an expedition led by mfalme Mataka, landed on the shores of Kitaubani at the site of modern-day Msua. Mataka had fled his homeland of modern-day Maucha both to escape violence at home and to re-establish his wealth through new economic holdings. After a long journey fraught with adverse conditions, conflicts with local authorities, and other innumerable hardships, was the island of Kitaubani: according to popular folklore, in his relief at completing his journey, Matake proclaimed the site kituo wa pwani, or the Coast of Respite. As Mataka carries an almost-mythified status in Kitauban consciousness as one of the first kings of the island, this story has persisted and grown to be the most popular folk etymology for the name of the country.

History

The first settlers of Kitaubani likely crossed into the area from mainland !Africa via maritime crossings of the Ufa Channel.

Arrival of Mataka

Second Msua Period

Modern Kitaubani

The late 1950s and early-mid 1960s saw increasing frustration with Yatasu's continued rule. With other Bahian nations decolonizing into (at least nominal) republics, sentiment was high for the establishment of a republic in Kitaubani. Disillusioned with the continued suspension of the Constitution's promulgation and buoyed by international support, protests began calling for anything from the promulgation of a new Constitution to the abolition of the monarchy entirely. During this time, the Royal Police and Royal Army intelligence agenices conducted small-scale, targeted purges of both ethnic separatist and Councilist dissidents; the Kitauban Dirty War weakened public and international support for Yatasu, though it is arguable whether or not he had lost control of these security forces by the end of his absolutist reign. Wishing to retain life and livelihood, Katasu bowed to the pressure from both domestic and international sources (namely from the United Bahian Republic) and accepted a much more ceremonial role, leaving open the door for the political parties kept much in limbo to step forward into fully legitimate politics. The first Premier was a moderate Pan-Bahian and social democrat named Danjimma Ringim, who then executed numerous policies designed to placate radical sentiment and disarm potential Councilist sympathies. This led to a gradual restabilization of Kitaubani's political scene over the ensuing decades, thanks largely to the support of business elites from several different minority ethnic groups lending much-needed political capital to Ringim's reforms in the interest of keeping the peace. Yatasu, not wishing to tip the boat and recognizing the bad public image he already had, reluctantly acquiesced to many of the political changes solidfying the supremacy of the parliamentarian system in Kitauban politics. The death of Yatasu in 1972 was in hindsight remembered as the final transition point from "old Kitaubani" to "new Kitaubani."

Geography

Climate

The climate of Kitaubani is primarily influenced by the Ufa Channel, to the country's west, and the !INDIAN Ocean to its north and east. As a result, much of Kitaubani is classified as tropical savanna, tropical wetland or tropical monsoon climates on the Rajoelina climate classification scale; the only areas to be not labeled as tropical are the humid subtropical regions farther inland or the foothills to the very south of the country.

Administrative divisions

Kitaubani is subdivided into 22 departments, further subdivided into districts. These districts are centered around a significant autonomous settlement with a city council, with the remaining territory divided into wards overseen by municipal, village, or rural councils. The departments of Kitaubani were drawn for the most recent time in 1970, designed to roughly correspond to equal population size per district. Due to substantial industrialization and urbanization in the intervening decades, however, there now exists a substantial population disparity between rural and more urbanized departments.

Demographics

Ethnicity

Language

KiUngwana, as the language of the royal family and elite merchant caste, has for centuries served as the lingua franca of the empire. Education in the Ungwana language is mandatory across the nation, though provisions exist for schooling in regional languages.

Education

Religion

The state-sanctioned religion of Kitaubani is Fombava. Despite state sanction and support dating back centuries, Kitaubani is (and has been for centuries) peopled by believers of a diverse array of religions. Part of this religious diversity can be explained by the decentralized nature of Fombava itself; rather than a cohesive religion with a singular doctrine, the faith is defined by an array of priestly schools and community religious leaders, all interfacing with each other and with local ritual customs. Additionally, though the Kitauban Decennial Census of 2020 records XX% of the population follows a "traditional or folk religion," the line between the aforementioned and Fombava practice is often blurry due to the latter's frequent coöpting of the former. Additionally, owing to the region's centuries-old role as a major trade entrepôt, numerous groups of people have migrated to the region, bringing their religions with them. In the interest of increased trade profits, successive governments of the Pwani Coast generally opted for a policy of religious tolerance. In the modern day, though they lack the protection and support of Fombava, other religions generally persist without persecution. Such religions include Manichaeism (the largest of its kind), X, and Y. New religious movements, however, may face heavier scrutiny if they take influence from religions deemed "foreign" to Kitauban values by law enforcement authorities.

Government

Kitaubani is a unitary constitutional monarchy, governed under its 1969 Constitution. The head of state is Queen Majani I. Under the Kitauban Constitution, the monarch holds authority as commander-in-chief of the armed forces and ultimate source of government authority. The monarch is provided a parliamentary head of government, known in KiUngwana as the Wakili wa Ikulu or palace steward (though typically, this term is translated as Chancellor). Currently, the Chancellor is Enzi Wario, an admiral and non-partisan. The Chancellor is typically elected from the ranks of Kitaubani's parliament, the National Assembly, with final approval granted via royal assent. Chancellors serve at the monarch's pleasure; the current Chancellor, Wario, was appointed without Assembly election by Queen Majani following the assassination of their predecessor, Mulele Kimachu, in February 2022.

Executive government functions in Kitaubani are channeled through a network of ministries, royal commissions and extra-ministerial bureaus that answer to the monarch through the Cabinet. The Chancellor exercises most of their authority as head of the Cabinet on behalf of the monarch for day-to-day operations. The monarch's guaranteed powers include, but are not limited to, the ability to finalize declarations of war, treaties, and international agreements; the ability to appoint and dismiss executive government officers; the ability to appoint judges; and the ability to reject draft laws from the National Assembly (aside from proposed budgets, which falls under the purview of the National Assembly).

Legislative functions of the Kitauban government are housed under the National Assembly, the nation's bicameral parliament. The lower house, elected through universal suffrage, is known as the Chamber of Representatives; the upper house is known as the Chamber of Peers and is comprised of hereditary appointments by the monarch and the noble leaders from various regions of the country. The National Assembly remains primarily the playground of the Kitauban elite.

Law

The Kingdom's laws are a mixture of several iterations of codified civil law and religious law based on the state religion, Fombava. The judiciary of Kitaubani, according to the Constitution, exists in two parts. The first is subordinate to the monarch (judges are selected by a committee of legal experts and approved by the monarch) and responsible for offenses against the codified, secular law. The other part of the judiciary, often translated as the canon court system, is responsible for infractions against religious law. While the religion is recognized as the state religion of Kitaubani, and receives certain privileges not given to other faiths, Kitauban subjects are still technically free to worship as they see fit. Regardless, the religious institution of Fombava is utilized as another arm of the state by the royal government. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the canon court system has been repeatedly diminished in scope and power by successive monarchs in an effort to curtail the Fombava priesthood's power and rein in the faith under royal supervision. As such, canon courts are unable to impose sentences higher than a fine of ₱15,000 or impose any incarceration. As such, canon court punishments are typically focused on rebuilding community trust and imposing a kind of restorative justice.

The Kitauban Constitution provides a limited set of rights guaranteed to Kitauban subjects. These include:

- The right to petition the government,

- The right to unobstructed movement within Kitaubani,

- The freedom to own private property, unless conflicting with overriding national interest,

- The sanctity of home and property against search and seizure, unless conflicting with overriding public safety interest,

Other rights are provided more conditionally, and are subject to revocation under royal prerogative.

In exchange for these rights, Kitauban subjects are obliged by the constitution to pay tax, serve in the military when called, and uphold the laws of Kitaubani. Additionally, the Constitution formally abolished the old Kitauban caste system, though social discrimination based on the caste system continues to this day.

Foreign relations

The foreign policy of the Kitauban state is dominated by two competing schools of thought. The first, known colloquially to outside observers as the "blue-water school," prioritizes economic and political relationships in the !INDIAN Ocean, up to and including dominance of the coastline either through political control or imperial influence. Proponents of the blue-water school point to the thalassocratic X Empire, which in the 18th century controlled much of the Ocean's coasts either directly or through mercantile agreements, as a model to emulate in the future. The most vocal proponents of blue-water foreign policy in the Kitauban government come from descendants of the nation's wealthiest merchant families and the Royal Kitauban Navy top brass; the two groups share a significant overlap in membership. In contrast, the so-called "brown-water school" consists of those elites, often from minority ethnic groups, with little connection to the overseas trade industry, and is associated with the Royal Kitauban Army. In contrast to the blue-water policy proponents, advocates of brown-water policy champion prioritizing relations with states in !Africa and on XISLAND, especially focusing on the Ufa Channel.

As a result of blue-water school influence, Kitaubani maintains developed relations with the Ngāti Onekawa-Nukanoa.

Economy

Kitaubani is often categorized as an lower-middle-income nation. Through a burgeoning industrial sector and nascent services sector, along with footholds in the global shipping industry, the nation has maintained one of the stronger economies in Bahia. Kitaubani holds the highest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita both nominally and in terms of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) in !Africa. Decades of relative political stability and peaceful transfers of power have helped encourage steady economic growth.

Major industries in Kitaubani include manufacturing, agriculture, shipping, and, increasingly, tourism. Shipping, especially in providing crews for international vessels and through flags of convenience, generates significant revenue and employs a large number of Kitaubans. Kitauban shipping crews and other foreign workers provide a significant influx of foreign capital through remittances.

Transportation

Kitaubani's transport network is diverse, with numerous methods available connecting settlements, the islands, and the country itself to the outside world. The Kitauban rail network is relatively robust, including both intercity service, freight transport, and in Kwamuimepe and Msua, limited urban light rail.