Uniforms of Themiclesian armed forces: Difference between revisions

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

==General trends== | ==General trends== | ||

The use of identical pieces of garments was normalized in Themiclesia relatively recently, it previously being the prevailing notion that unit identity was sufficiently expressed through badges in the shapes of scarves, arm-bands, and ribbons on hats. In the civil context, the colour of one's over-robe took on some significance at the royal court: barons and royal retainers wore reds and purples, while bureaucrats wore black. But this practice did not spread to the armed forces until the 17th century and probably under Casaterran influence, when professional regiments were commanded to be dressed in distinct colours at various times. It is believed the practice originated as temporary designations in the order of battle, though reasons of economy may have the colours to become permanent. | |||

The | The practice of wearing coloured coats was not universal and particular to the legion in which the regiment was placed. It should be noted that, while colours were regulated, the style or cut of the coat was not; uniformity principally arose in the interest of utility and fashion, as it had not been then though, as later it was, that morale could be encouraged via identification with badges. Casaterran-style coats became fashionable in parts of Themiclesia in the late 1600s to about 1730, when modified domestic designs influence again dominated, yet some units were certainly then outfitted in the Casaterran style. These major clothing changes were often financed by the royal treasury on the pretext of replacing attire worn on campaign but also for showing royal favour. | ||

The | The awarding of clothing became obsolete in the long peace after 1796, but the colours of the regiments remained in effect. | ||

==Land forces== | ==Land forces== | ||

Revision as of 03:15, 10 August 2021

This page catalogues the uniforms of Themiclesian armed forces. Early Themiclesian military bodies rarely possessed distinctive clothing, as state-issued body armour usually identified its wearer. After the obsolescence of armour, the government sometimes mandated certain emblems be used, though most soldiers and sailors had to supply their own clothes. Casaterran-style uniforms were introduced in the early 19th century, and dress uniforms since have followed Casaterran social norms. In more recent times, efforts have been made to standardize battle equipment and clothing for effectiveness and economy, though dress uniforms tend to be peculiar to the unit, more so if it had a long history or distinct role.

Terminology

Themiclesian armed forces use the same terminology as civilians to describe levels of formality in various uniform styles. Generally, there is only one uniform described as full dress applicable to any serviceperson, while there could be several half dresses and undresses. Note that this terminology strictly describes formality from a civilian perspective and does not describe how these forms of dress may be used for internal functions. In the 19th century, military uniforms switched to the Casaterran style and followed civilian standards of formality very strictly, creating little need to stipulate equivalencies between them; however, as they diverged at the start of the 20th, such stipulations were formalized.

Degrees of formality

- Dress (具服, kwa-bek): literally "full dress", a chance similarity between Tyrannian and Shinasthana terms. For those with rights to attend court, it is also called court dress (朝服, traw-bek). Full dress, by convention, is equivalent to the white tie worn by civilians. Full dress in conservative units almost always include a tail coat, waistcoat, and cravat of some kind, with shirt collars worn standing up. In more liberal ones, a full dress is simply the most formal dress code endorsed. While elaborate decorations were once common on full dress uniforms, these became uncommon by the end of Queen Catherine's reign (r. 1837 – 1901). Austerity had become the standing order of civilian men's wear, compelling the military to conform. Today, for units that issue a full dress, they typically reflect the fashionable near-black colours of this period, with lapel pins and non-contrasting ornamentation on the waistcoat remaining acceptable.

- Half dress (從省服, dzwang-sring′-bek): lit. "reduced dress". Half dress is considered equal to civilian frock coat or morning coat during day time and dinner jacket at evenings. In conservative branches, a frock coat may remain in use and be called a frock coat (西長表, s.ner-trang-pru), but this is now the exception rather than the norm. The Themiclesian Air Force led the forces in recognizing the blazer as a half dress in the 1950s, since frock coats, morning coats, and dinner jackets became antiquated in the civilian world at this time. Formerly, a half-dress required a knee-length skirt for men and ankle-length one for women, as a rule of thumb.

- Undress (褻服, sngyat-bek): anything which does not categorize into the two above.

Underlying history

The concept of uniforms in Themiclesia, for much of recorded history, was not represented in the armed forces, but the civil service and aristocracy. Since civil servants were both socially distinguished and possessed public authority, it became proper for them to dress to express the same. On one hand, dress express power derived from the crown, and to denote positions relative to each other within the hierarchy. On the other hnad, these markers co-existed with the need for self-expression, which represented civil servants' financial and cultural capital as aristocrats, outside of the hierarchy of public officialdom, and the dignity between peers, often used against royal power. Even though one may speak of a "uniform" for civil servants, few elements were uniform across the civil service; hats, sashes, and seals were symbols of difference, not similarity.

The earliest forms of uniform apparel in Themiclesian history were armbands, which identified the wearer's position (such as left flank or skirmisher) during combat; they were apparently specific to the operation, as new armbands were issued for operations requiring a different configuration of units. Uniforms that identified the wearer's unit affiliation rather than ad hoc position appeared much later, attested from the 14th century in the Colonial Army, which wore all black. Most of its early recruits were ex-inmates from labour camps, in which criminals and their descendants lived, and black was the characteristic colour of inmates uniforms; black dye was also cheap and served to identify members of the unit from ordinary Themiclesians, who avoided wearing black due to its stigma. However, most units, even professional ones, fought without true uniforms into the 1700s. Their general adoption occurred in the first half of the 19th century, under Casaterran influence.

General trends

The use of identical pieces of garments was normalized in Themiclesia relatively recently, it previously being the prevailing notion that unit identity was sufficiently expressed through badges in the shapes of scarves, arm-bands, and ribbons on hats. In the civil context, the colour of one's over-robe took on some significance at the royal court: barons and royal retainers wore reds and purples, while bureaucrats wore black. But this practice did not spread to the armed forces until the 17th century and probably under Casaterran influence, when professional regiments were commanded to be dressed in distinct colours at various times. It is believed the practice originated as temporary designations in the order of battle, though reasons of economy may have the colours to become permanent.

The practice of wearing coloured coats was not universal and particular to the legion in which the regiment was placed. It should be noted that, while colours were regulated, the style or cut of the coat was not; uniformity principally arose in the interest of utility and fashion, as it had not been then though, as later it was, that morale could be encouraged via identification with badges. Casaterran-style coats became fashionable in parts of Themiclesia in the late 1600s to about 1730, when modified domestic designs influence again dominated, yet some units were certainly then outfitted in the Casaterran style. These major clothing changes were often financed by the royal treasury on the pretext of replacing attire worn on campaign but also for showing royal favour.

The awarding of clothing became obsolete in the long peace after 1796, but the colours of the regiments remained in effect.

Land forces

Themiclesian land forces started to assumed their modern structure under the Army Acts of 1921. While fiscal and operational unity was achieved by the Pan-Septentrion War, the Conservatives have generally opposed attempts to consolidate the army beyond those aspects, preferring to allow each unit to retain a measure of symbolic independence. This is most clearly reflected in the dress uniforms of the army, which still vary by region, regiment, and department.

Today, the army can be divided into four parts—the Consolidated Army, Reserve Army, Territorial Forces, and Militias. The Consolidated Army, the main standing army, and the Reserve Army are both administered by the central government, and they share the same set of uniforms for the most part. The Territorial Forces are units raised, with parliamentary approval, by ethnic minorities groups sharing in nation defence. These units possess distinct uniforms, though their activities, some statutory exceptions aside, are also co-ordinated centrally. The Militias are nominally under prefectural administration, though modern administrative rules require central permission to most local action on them. Each prefecture establishes uniforms for its militias.

The ordinary rule of the modern era, since the Pan-Septentrion War, is that field uniforms are co-ordinated by duties and environment, irrespective of unit. Thus, an air force crew member is likely to be wearing the same fatigues as an army soldier stationed in the same facility. There may be minor variations according to manufacturer and issuing authority, but principal characteristics are similar across the armed forces.

Consolidated and Reserve armies

The Consolidated Army (聯兵, rjên-prjang) issues uniforms to units that do not have peculiar uniforms. The units formerly of the Capital Defence Force, South Army, and Royal Signals Corps, and those established by statute before 1921, continued to issue peculiar uniforms. Since 1921, a number of units have conformed to the army's standard patterns, though others retain distinctive attire. In the late 19th century, many units adopted the sack coat as an undress or field uniform. These sack coats originally differed from dress coats only in cut, being shorter and less structured (thus cheaper), but by 1910 many units have mandated drab or khaki sack coats for field use. In the Prairie War, around half of the units wore the standard 1922 uniform, while the other half retained peculiar uniforms.

The field uniform of 1922 consisted of a drab green wool sack jacket, waistcoat, trousers, linen shirt, undershirt, drawers, braces, cravat, helmet, wool socks, and boots. This combination was particularly close to the Western University Regiment's uniforms. Branch and unit affiliation and rank were indicated through located on caps, lapels, collars, shoulders, and sleeves. While servicepersons generally found satisfactory the uniform's durability and aesthetics, many suffered heat strokes marching through the desert in the summer of 1926 and 27. Some threw off jackets and waistcoats, shocking officers who considered shirts and braces underwear. The black cravat was reviled as it "created a noose of heat around their necks" and was not lauderable. Most officers permitted soldiers to add and remove articles as the climate dictated, and this practice was sanctioned in 1929 by the War Secretary's ordinance.

The field uniform was updated for comfort and economy with conscription imposed in 1936. The sack jacket and skirt of the dress shirt shortened considerably, and the waistcoat disappeared. Extra volume in drawers and sleeves were too minimized while permitting mobility. The cravat was replaced by a drab knit tie that was nominally worn over standing collars, but most soldiers tucked them into the shirt instead. The sack jacket acquired two chest pockets, not frequently used as webbing ran directly over them; the trousers acquired four pockets, two on the side seams and two pouches over the thigh. In 1940, the wool jacket and trousers were replaced by canvas, further adressing overheating and as a substitute when Themiclesia lost much of its wool supply.

A summer variation of the 1936 uniform was issued in 1941, with shorts instead of trousers and discarding the jacket and necktie entirely. This uniform was in consideration for at least two years, but conservatives voiced concerns that it exposed too much of the body "to be decent anywhere except the most extreme heat," as much as fearing soldiers would reject it. This reservation proved specious, and the summer variation was in use year-round in Dzhungestan and Maverica, where the heat, combined with humidity, was even more formidable for Themiclesians accustomed to colder climates.

The Reserve Army (聯戲, rjên-ng′jaih)...

Territorial Forces

The Territorial Forces (方兵, pjang-prjang)...

Militias

The Militias (郡兵, ′k.ljur-prjang; 邦兵, prong-prjang)...

As with militias, naval personnel were historically responsible their own clothing, with few regulations applied. The navy was responsible for selling the fabrics to sailors, but the rights to sell goods onboard were usually auctioned, and the winner often inflated prices with an effective monopoly. As a result, most sailors preferred to bring fabric or make purchases on port calls.

The earliest Casaterran-style naval uniforms were more similar to a dress code than uniform in the modern sense. In 1819, officers and men were ordered to dress in a blue coat, white waistcoat, and trousers; as pictorial evidence demonstrates, any blue tailcoat was acceptable, mutatis mutandi. It was acceptable to add private clothing to the ensemble, as by custom a woollen jacket was worn over the waistcoat; as this article was not formally regulated, it was used as a canvas for a crew to identify sartorially with their vessel. The naval dress code of 1819 was not amended until 1920, when illustrations were promulgated to standardize the appearance of naval costumes.

Consolidated Fleet

Sailors often sought to preserve the costly overcoat and waistcoat, and it become typical to wear only the shirt and cravat on normal duty. Though this was ostensibly out of order, it was tacitly permitted. Early portraits show sailors with closed collars and neatly-tied neckcloths, but by 1830 this had become uncommon. Under Casaterran influence, neckties loosened, allowing collars to open and flap down over their shoulders.

Around 1840, commentators remarked how much of a sailors could be seen unclothed, provoking the Admiralty to require sailors to fasten their neckties and wear a frock coat when publicly engaged. This ordinance had little effect, since neckcloths grew only looser through the decade. By 1850, the neckcloth was similar in function to a scarf, and the bow was abandoned for a four-in-hand knot. It is not clear why sailors preferred this knot, but it is possible that loops on a bow was seen as a hazard with the rigging. In the 1905 uniform update, the obsolete tail coat was withdrawn for enlisted men, though officers were still expected to supply their own tail coats for formal functions.

Marines

The Marines originally had the same dress uniform as sailors. Yet as their duties soiled clothing less, marines generally wore the naval jacket and waistcoat as regulations stipulated. The woollen jacket worn by sailors is shared by marines, bearing the crew's insigne. That it be visible, the dress coat was never buttoned. In 1827, the Admiralty ordered the Marines to wear waistcoats peculiar to their regiments. In 1837, all Marines regiments were ordered to wear a blue frock coat for duties on shore and drilling. As in other regiments, the influence of civilian fashion predominated in the 19th century, inducing coats to darken until basically black, as other colours became undignifying for men in high society.

Around 1900, a navy blue sack coat was worn in place of the frock coat in informal situations. In 1927, the Marines adopted an exact copy of the Consolidated Army's standard field uniform issued in 1922.[1] The 1st and 2nd Regiments were deployed in Maverica in 1944 – 45 and were issued, from the Consolidated Army's exchequer, the same winter and summer field uniforms.

Coast Guard

In 1921, the Coast Guard was formed by amalgamating the prefectural revenue marines and other maritime safety apparatūs under the Home Office. As the force had no formal predecessor, the Home Office followed the example of the TAF and selected a foreign design—that of the Camian Marines—for the new Coast Guard. This was consonant with the foreign policy of 1920s seeking to enhance bilateral relations with Camia. However, as coast guards were expected to work in uniform, changes were made in the interest of utility. Pockets were added, and dress shoes were replaced with boots that could be polished to a patent finish as required. The hat was also changed for naval officers' peaked caps at the behest of the Home Secretary. Otherwise, the navy blue tunic and white trousers were similar to their Camian originals. The uniform was also the first dress uniform in Themiclesia that did not include a waistcoat or necktie. Many Coast Guard officers did not like these facts, along with that of the trousers' white colour, as it rendered their uniforms unsuitable for civilian settings, where both are requisite and white unfashionable.

Aerial forces

The uniforms of the Themiclesian Air Force were revolutionary in the domestic military sphere that it was an imported design. This formerly was somewhat taboo in the same way direct imitation of another nation's military precepts was in the Army Academy.

Aviators

The initial pattern of the Air Force dress uniforms was heavily influenced by the Tyrannian Royal Air Force, which showed influence from the Royal Army. It consisted a shirt with fold-down collars, necktie, trousers, suspenders, belt, Sam Browne belt, waistcoat, and overcoat, the latter two with standing, closed collars. The trousers were deep, greyish-blue with a bold indigo stripe on the sides, with a slight blouse where it tucked into boots. The waistcoat and overcoat were both "air force teal", a creamy teal colour so-called due to its ubiquity on Air Force uniforms. The collars on the overcoat were a slightly deeper hue of the same colours. Aviators wore black, knee-length boots, with the top two inches customarily folded down for tighter fit.

Sartorial editor M′rjang wrote that this forced the boot to hug the contours of the wearer's calf muscles, which created a sharper and "literally more muscular" appearance that was intentional. Some historians believed that early Air Force leaders were overidingly concerned with predatory War and Navy Ministries hoping to annex the Air Force, leading it to adopt an aggressive and impactful style that broadcasted its independence from either, whose uniforms were both characterized by following civilian fashions. The Sam Browne belt was worn by aviators, who carried pistols for self-defence; other services, ordinarily not permitted to carry weapons off duty, envied this privilege. It was also a contravention of Themiclesian social etiquette, which demanded disarmament in urban areas (邦中); this included not only weapons but their accessories, such as scabbards, holsters, pouches, and belts. Only the Gentlemen-at-Arms and high-ranking civil servants were excepted from this rule, and its extension to the Air Force was perceived as the government's vote of confidence in them.

The TAF led Themiclesian forces to adopt the blazer as a half-dress uniform, for the entire branch, in the early 20th century. While unit characteristics, decorations, and badges had all but been purged from formal dress codes to conform to civilian norms in the late 19th century, the forces in general sought to transfer their insignia onto garments in ways that would not conflict with those. The TAF, after encountering resistance against colourful dress uniforms in formal settings, started wearing blazers that were common for clubs and sports teams, for informal settings. In 1921, the TAF hosted the first inter-service sports tournament and commanded its attending officers to appear in a uniform blazer. This idea soon spread as blazers were sufficiently informal that unit insignia and decorations could be worn in full colour without stirring social condescension. In the 50s, this blazer was legitimated as a working uniform for the TAF.

Ground crew

Air infantry

Themiclesia's air force ground forces, the Themiclesian Air Force Regiment, were originally ordered to wear a blue frock coat, teal cravat, and grey chequered trousers as their dress uniforms. Most of the regiment procured their uniforms locally, from Tonning tailors, who re-used the templates and fabrics for marines' uniforms. This gave the TAFR the unwanted monicker of "recoloured marines" (易色冗人, lêgh-s′rjek-njung-njing) of which it wished to be rid. In 1927, Parliament altered the unit's uniform rules and allowed the Air Ministry to alter their uniforms, which then changed to be similar to the rest of the air force, but with a burgundy collar instead of dark teal for aviators and green for ground crew.

Themes

Women's uniforms

The official role of women in the armed forces expanded in the 19th century. The Convalescence Service, set up in 1863, employed women in considerable numbers and appointed female officers on the grounds of professional knowledge as early as 1870. A sprinkling of female officers existed in other locales, but many did not discharge their offices personally, leaving it instead to a male lieutenant. The Convalescence Service did not employ military uniforms in the modern sense of the word, it being judged inappropriate for a convalescing environment, yet a standard nursing attire was used under an apron. Female officers did not usually wear a nursing attire, but ordinary daytime outfits. Some female officers in other places wore uniforms, but most did not.

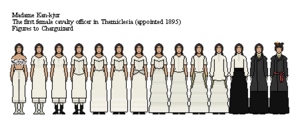

The oldest surviving set of uniforms worn by a female officer who did personally discharge office belonged to Lady Kan-kjur (1854 – 1911), a cavalry captain between 1895 and 1899. Her uniform can be described as a feminized version of that of her unit, the 410th Signals Cavalry. She wore a grey redingote and white chemisette approximating male officers' frock coats and shirts in like colours; underneath, she wore all layers typical in a daytime outfit belonging to a woman of high status.[2] While the undergarments are formally reminiscent of civilian clothing, they were specialized and ruggedized to accommodate her professional requirements. The fact that these items were in a trunk together with her uniform, and not with her other garments, also suggests she considered the undergarments part of the uniform. Similar measures are often found on uniforms belonging to other aristocratic women in the armed forces, but there also exist examples without.

There were no firm regulations over what a female officer's uniform should look like relative to that of her male peers until the Pan-Septentrion War. For enlisted female servicepersons, who found work as clerks after 1901, regulations establishing colour and cut appeared in different units the 1910s. Early designs typically included bodices approximating mens' coats but a floor-length skirt. Women were expected to conform to contemporary precepts of modesty, though these were not uniquely military requirements. Structured undergarments, like the corset, remained in use by some, if not most, female servicepersons. Enlisted women were expected to acquire undergarments privately, as most were commuted from home rather than lived at a garrison. For fear of voyeurism, female servicepersons were cautioned in 1921 against fashionably shortening their skirts, but some nevertheless did so with no great objection from above, as womens' clothing had dramatically changed since the 1890s.

The woman in military uniform became a cultural symbol of female independence in 1920s Themiclesia, as the armed forces offered stable employment and some opportunities for advancement irrespective of her origins or marriage.

Enlisted uniforms

Historians note that the vast majority of uniforms surviving from the 1800s belonded to officers, with but a minuscule number of enlisted examples, in spite their obvious numerical superiority. Several factors may have contributed to this imbalance. Officers often made new uniforms when they took new commissions and retained the older sets as mementos, and their privileged economic condition enabled them and their successors to preserve old uniforms, often unconsciously in an attic or crawlspace at a large house, for many years. In contrast, enlisted men often modified their uniforms for civilian use or sold them at discharge to a clothier, where another serviceperson might buy it, or it may be altered for civilian purchase. Uniforms worn beyond mending or selling might be cut into rags, and when even that failed, they became candlewicks or filled blankets and winter coats.

Despite the paucity of enlisted uniforms, they show salient differences from officers' uniforms, allowing historians to interpret their often-different attitudes in military employ. In an era without strict uniform regulations or those outright ignored, officers uniforms were not only newer but frequently more fashion-forward, while enlisted uniforms showed signs, with or without remodelling, from older designs. When officers' uniforms darkened according to civilian fashion in the 1870s, enlisted uniforms were often unfashionably colourful, remaining blue, red, green, and yellow; some were dyed to pursue a more fashionable colour, while officers' uniforms are almost always made in a fashionable colour. The quality of fabric and workmanship also differed dramatically between officers and enlisted rates.

Holes from repeated use suggest that enlisted soldiers used more pins, possibly to hold medals, than officers, who preferred a cleaner appearance. These differences are frequently reflected in the diaries of enlisted soldiers, one commenting about officers' omission of insignia "to appear superior". In a similar vein, a well-cut coat in a good fabric was often seen as the privilege of an officer, while the enlisted man often contended with anything that provided adequate warmth. "The fashionable, clean, and well-made coat was the badge of an officer, like it was to the middle-class man," writes historian A. Gro, "no amount of chevrons, bars, or shiny brass could displace the symbol of social superiority. There is even a letter written by a private in 1873 begging his comrade not to wear his new medal, because that exposes his 'attachments'."

Notes

- ↑ The ordinance sanctioning it read, "exactly the same in style, cut, and appearance as that of the Consolidated Army as the Secretary of State for War has ordained in 1922, or shall have ordained since then, whichever of the two being the later. Sign manual." Dr. Ngang Krjim, who served with the Marines between 1919 and 1930, recalled that "the rumour was that the decision was made at least in part to spite the admirals, because they blocked our plan to merge with the Consolidated Army in 1919 and also because Lord Huk [Captain-general of Marines 1926 – 27] did not want to show his chest, which he stood convinced many sailors did to cause outrage in decent society. Lord Huk was the kind of man who kept a brush in his tail-pocket, to rid his coat of hair or lint."

- ↑ Altogether, her outfit for meeting other officers consisted of drawers, linen shift worn against the body, stockings, garters, whalebone corset, two under-petticoats, padded bustle, over-petticoat, corset cover, chemisette, over-skirt, redingote, boots, gloves, and tricorne.