Rajyaghar

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Kingdom of Rajyaghar साम्राज्य राजांचे घर | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Jai Maharaja" Hail to the King (English) | |

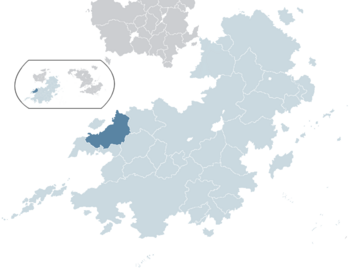

Rajyaghar on the continent of Coius | |

| Location | Continent of Coius |

| Capital | Kinadica |

| Official languages | Sanyukti |

| Recognised regional languages | Zubadi, Pardarian, Vedaki |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion | Tulyatan (major), irfan (minor) |

| Demonym(s) | Rajyani |

| Government | Federal, Parliamentary, Constitutional Monarchy |

• Maharaja | Krishan VII |

• Crown Prince | Prince Akash |

• Prime Minister | Madhava Thakur |

• Chief Justice | Vishnu Kapadia |

| Legislature | Shahee Sansad |

| Significant events & Formation | |

• Vikasan Era | 100 BCE - 500 CE |

• Rajyaghar Colony created | 19th June, 1819 |

• Declaration of Independence | 23rd July, 1947 |

• Independence from TBD | 14th November, 1953 |

• The Punaruddhaar | 1970s |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 84,267,147 |

• 2017 census | 81,479,432 |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Per capita | $14,255 |

| Currency | Rupee (RHR) |

| Time zone | UTC-2 (UTC) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +52 |

| Internet TLD | .ra |

Rajyaghar, officially the Kingdom of Rajyaghar, is a country in the Satrian region of the continent of Coius. Bound by the Acheloian Sea on the North, Rajyaghar shares land borders with Zorasan to the east; Ajahadya to the south; and Devagara and Ladaca to the west.

In the late 1940s, the tulyatan communities feared that the pardarian irfanics in the east would be emboldened by the revolutions taking place in Zorasan and they feared that the pardarian irfanics would try to conduct a similar revolution in Rajyaghar. As a result, the non-irfanic communities, including their middle class and elites, rallied behind the monarchies of the former rajyani kingdoms, particularly the Sanyukti Maharaja; Krishan III. In November 1952, the non-irfanic leaders of the independence movement held a congress in the ancient sanyukti city of Kinadica, where they agreed that they would back a constitutional monarchy for a post-independent Rajyaghar. The congress also decided that it would be Krishan III who would be the first post-independence Maharaja. During the independence negotiations with [colonial power] in February 1953, the pardarian irfanic independence leaders were out-maneuvered early on and were out voted by the non-irfanic independence leaders and the constitutional monarchy system with Krishan III as Maharaja was agreed to.

Whilst Rajyaghar’s main industry is agriculture, it has a growing information and technology sector. In the last two decades, due to government emphasis on education and literacy, the nation has seen a sharp rise in literacy rates and has seen an emergence of a growing middle class. This change has also seen an influx of rural citizens move to the urban centres which has further grown the cosmopolitan industries of Rajyaghar. However, due to inequalities in the distribution of education and infrastructure, as well as limited resources, not all of Rajyaghar has benefited from these changes and the income inequality of the state has increased.

Etymology

The name "Rajyaghar" is derived from the sanyukti words of "Raja" and "Ghar" meaning King and Home respectively. Translated literally, Rajyaghar means home of the kings and is a reference to the name given to the land that makes up modern day Rajyaghar before colonisation; Rajyamina. 'Rajyamina' translates to land of the kings and the land that made up modern day Rajyaghar was called this due to the dozens of Kingdoms that existed there prior to colonisation. Throughout the colonial period, the kingdoms would be transformed into colonial provinces which retained their monarchs as ceremonial figureheads under the colonial governors.

Modern day Rajyaghar is still considered the land of monarchs due to its form of government (constitutional monarchy) and its federal structure in which all Union States have a ceremonial provincial-monarch who is the descendants of the Union States former Monarchs when the Union States were minor kingdoms before colonisation.

The usual way to refer to a citizen of Rajyaghar is "Rajyani"

History

| Timeline of Significant Rajyani Eras | |

|---|---|

| Pre-250 CE | Ancient Rajyani Civilisations |

| 250 - 800 | Naratha River Civilisation |

| 800 - 1000 | Andhara Period (Dark ages) |

| 1000 - 1150 | The Parivartana (transformation) |

| 1300 - 1600 | Vikasan Era |

| 1600 - 1800 | Age of Sanyukt |

| 1816 - 1841 | Second Andhara |

| 1841 - 1935 | Colonial Era |

| 1965 - 1967 | The Emergency |

| 1970 - 1980 | The Punaruddhaar (revival) |

| 1980s - Present | Modern Era |

Ancient Rajyani Civilisations

The earliest known records of humans in Rajyaghar was around 65,000 BC with historical records of this era being minimal at best. From 6,000 BC, historical records begin to show evidence of basic structures for residence, the rearing of animals and use of crops for food along the coastline and along major rivers which progressed inland. These areas developed into the ancient Rajyani Civilisaitons. Due to their relative isolation from one another, the settlements developed independently for thousands of years until around 2,000 BC when there was increased communication between the civilisations and trade began to emerge.

From 2000 to 300 BC, the development of the tulyatan faith began to emerge and flourish amongst the ancient rajyani civilisations as did the ancient language of matrabasha. It is also agreed that it is during this period that there was significant migration of Satari-Euclean migration to the region which further led to the development of the matrabasha language and tulyatan faith. Some of this migration also led to small tribes and communities developing deeper inland in the southern mountain ranges and the eastern forests. These distant tribes and communities quickly lost contact with those in along the coast and rivers.

It was also during this period that the development of the clan system emerged with various tribes and communities developing unique practices, traditions and rituals and with clear leadership structures which is evidenced by some of the archeological findings along the Naratha river and coastline; which showed clear signs of chieftan residences in the centre of ancient clan settlements. It was also during this time that a caste system appeared to have developed. On buildings and tools throughout the ancient rajyani civilisations there appear to be symbols which denote an individual or structure's role in society. For example, there is the symbol of the trident which can be found, in one artistic form or another, on the walls of the chieftains homes.

One of the largest areas of development was along the Naratha river, the largest of the Rajyani rivers. The rapid development in this areas was due to the increasing trade occuring between the communities and tribes along the river and the prosperity of their agricultural practices which flourished on the fertile river banks. The continued trade, agricultural development and use of the shared matrabasha language and of the tulyatan faith, increased the coalescence of these communities and the wider ancient rajyani civilisations, which resulted in the development of the Naratha River Civilisation by 250 CE.

Naratha River Civilisation

Around 250 CE, the small tribes and clans of the Naratha river and Rayjani coastline had consolidated into dozens of monarchies which became known as the early kingdoms (Kirokirajya). Due to the shared language (matrabasha), clan system and faith (tulyata), this period of time and the Kirkoirajyas themselves are known as the Naratha River Civilisation.

The Kirokirajyas began to expand further inland away from the coast and river banks towards the more isolated clans in the southern mountain ranges and eastern forests and lowlands. As they expanded further inland, they took with them the matrabasha language and tulyatan faith. Throughout this time, various Kirokirajyas would coalesce through marriages between the children of clan leaders, alliances or through war. This led to the rise of larger Lavakarajyas (minor kingdoms), which, whilst larger in size and population, were fewer in number overall compared to the early Kirkoirajyas.

By 700 CE, the Lavakarajyas had begun to develop major settlements with capital cities emerging. The increased urbanisation within the Lavakarajyas led to the rise of non-tulyatan faiths and the increased trade and communication with the eastern clans had led to the introduction of the Irfan faith into the Naratha River Civilisation. By 800 CE, the differences in religion, culture and language between the western tulyatan Lavakarajyas and the easstern irfanic Lavakarajyas led to military conflict and war. This marked the end of the Naratha River Civilisation era and the dawn of the Andhara Period (Dark Ages).

The ancient Cāṅgalā vēḷa skrōla of the early Sanyukti Raj, a tulyatan Lavakarajyas on the north-western coasat, reveals that, between 600 and 800 CE, the eastern lowlands and forests were ruled by pardarian irfanic dynasties that traded and had strong relations with the Heavenly Dominions of Zorasasn. In western Rajyaghar, from the southern mountain ranges to the northern coastline, tulyatan dynasties ruled over the minor kingdoms and relied heavily on trade between themselves and with travellers from Euclea which had begun to develop trading relations with the tulyatan coastal kingdoms. It was during this time that the role of women began to expand within the tulyatan kingdoms due to their increased role at home as matriarchs as sons and fathers became warriors, and due to the reverence directed towards women due to the role in tulyatan texts.

Due to the stark religious differences between the western and eastern minor kingdoms, the tulyatan dominated western ones retained the name of Lavakarajyas, led by Rajas, and the irfanic dominated eastern kingdoms became known as Sultantes, led by Sultans.

Andhara Period

The Adhara Period refers to the 'dark ages' of Rajyani history and was a period of total war between the Lavakarajyas (low kingdoms) that dominated Rajyaghar.

The Parivartana

The Parivartana marked the end of the Andhara Period and saw a transformation, which is where the name comes from, in Rajyani culture. The new age saw a period of enlightenment and advancement throughout Rajyaghar.

Vikasan Era

The Vikasan Era was the glory age for the Middle Kingdoms of Rajyaghar. The Era saw the cementation of the multiple middle kingdoms as sovereign states. The era also ushered in an age of war which saw rival kingdoms clash over territories, ideologies and emerging differences in culture. It was in this era that the relations between Tulyatan and Irfanic communities broke down and resulted in multiple wars on religious grounds. Due to the balance of power between the Kingdoms, no one kingdom dominated Rajyaghar.

Age of Sanyukt

The Age of Sanyukt quickly brought about an end to the balance of power that existed between the middle kingdoms in the Vikasan Era. After decisive victories in the Coastal War, the Sanyukti Empire dominated north-western Rajyaghar and was able to exercise influence over most of the Tulyatan middle kingdoms. The Age of Sanyukt was a period of fewer conflicts and an era of stability for the Sanyukti Empire which saw no great threat to its supremacy in Rajyaghar.

From the 1770s onwards, Sanyukti dominance across Rajyaghar had resulted in a false sense of security and stability within the leadership of the Empire. Large amounts of the tax revenue collected by imperial authorities were diverted from the navy and army to the construction of monuments and infrastructure which, whilst increasing the size of the economy and culture of the empire, resulted in a weakening of its security. In 1795, the Sanyukti Empire was at the height of its power and, not having the appetite for conquest and having a lack of vision, Emperor Sooraj II summoned the heads of state of the other Rajyani Kingdoms to Kinadica where they signed the 1795 Peace Accords, ending centuries of conflict across Rajyaghar and confirming the borders of the various kingdoms. Following the peace accords, many of the Rajyani kingdoms reduced the sizes of their militaries to focus spending on their infrastructure and economies which further weakened the overall strength of the rajyani kingdoms. As a result, when the XX Empire landed its invasion force in the 1816, the weakened Rajyani Kingdoms were unable to put up any significant defence and the fall of the kingdoms began.

Second Andhara

The Second Andhara (Second Dark Ages) was the period of time between 1802 and the official formation in 1841 of the Rajyani Territories; the name given to the XX colony that made up modern day Rajyaghar. The period began in 1802 when an invasion force from the XX Empire landed on the north-western coastline of the Kingdom of Swarupnagar and the Sultante of Dalar Bewar. Due to the reduction in military spending and size of the Rajyani Kingdoms since the 1795 peace accords, navies had been reduced to merchant protection fleets and so the Swarupnagar navy provided little resistance against the well-tested and battle hardened navy of XX. By 1804, the small Sultante of Dalar Bewar had fallen and Swarupnagar was engaging in emergency peace talks with XX. Fearing a total loss of power, the Maharaja of Swarupnagar signed a treaty of suzerainty with XX which saw the Maharaja retain some domestic power. In reality, the Maharaja was King in name only as XX officials would dictate to the Maharaja what policies to enact.

Across the Rajyani Kingdoms, many saw the swift invasion of Dalar Bewar and Swarupnagar as a sign of what was to come and many began to re-arm and expand their militaries. But due to years of dismantling their military infrastructures, many of the kingdoms were unable to recruit enough forces to withstand the invasion forces of XX. In central Rajyaghar, the kingdoms rallied their weakened forces in their northern borders in preparation for an XX invasion, not knowing that in 1806, XX had signed secret agreements with the Sultantes of Raulia and Zulmat and the Empire of Parsa guaranteeing peace between them and XX in return for assistance in the invasion of the central Rajyani Kingdoms. In 1808, Raulia, Zulmat and Parsa, which made up the eastern rajyani states, invaded the central rajyani kingdoms in what became known as The Great Betrayal. The unsuspecting rajyani kingdoms were unable to withstand this eastern invasion due to their forces being predominantly in the north. Facing near guaranteed oblivion, the Kingdoms of Kodur and Bhankari, fearing irfanic dominance and suppresssion of the tulyatan people, signed treaties of suzerainty with XX, ending the sultante invasions.

By 1834, central and northern Rajyaghar was under the control of the XX Empire either through treaties of suzerainty or through direct occupation. In the west, only the Sanyukti Empire was able to put up any fight against the XX Empire. From 1826, Sanyukt and XX had been engaged in several small skirmisshes along their joint land border and at sea. The Sanyukti navy had managed to put up a significant fight but by 1836 the losses were mounting and the Sanyukti navy was unable to create more warships than were being destroyed by XX. In 1837, the final straw broke in the Battle of Deshmuk which saw Admiral Nandi's fleet sunk off of the coast of the major trading port of Deshmuk. With no naval force able to defend the Sanyukti coastline from a sea invasion, Sanyukti moral was crushed. The economic strains placed on the Empire was also causing domestic trouble with food shortages affecting the poorest communities. When the XX invasion of the Sanyukti Empire finally came in 1840, the country had been starved economically and was on the brink of civil war itself due to deteriorating conditions, poor morale and a devastated military and economy. In return for a bloodless takeover, Emperor Karan III entered into a suzerainty treaty with XX. By 1842, the remaining rajyani kingdoms fell through conquest to XX and the colonial era began.

Colonial Era

Due to the complex nature and divide and conquer tactics of XX in their invasion of the rajyani kingdoms, the organisation and governance of the territories was incredibly complex. After a series of riots and protests against XX control throughout 1842-1845, the XX Crown stepped in and ordered the colonial authorities to reorganise the colonies, which operated seperately from one another, into a single colony which would become the 'Rajyani Territories'. In 1847, new measures were brought into place to create the 'Rajyani Territories' in which a single Governor General, appointed by the XX Crown, would administer the colony. The existing treaties of suzerainty were renegotiated with the rajyani kings and sultans unable to protest due to the military strength of XX that had continued to increase since 1842. By 1851, the Rajyani kings and sultans had lost all significant powers as any power they did have was simply as a rubber stamp to colonial administrators who were appointed by the Governor-General to oversee the workings of each of the Kings and Sultans. Additionally, the Kings and Sultans were stripped of their titles and instead given the uniform title of 'Prince of the Princely State of [state]'.

The colonial era saw the birth of the 'rajyani' identity as prior to colonisation, there had never been a unified sense of a 'Rajyaghar' land or identity. It was also under the colonial regime that education became more common place with the colonial administration setting up the predecessor to the modern-rayjani education system; namely the mass construction of primary education schools and the establishment of colleges and universities in major cities, not just princely state capitals. Under the colonial regime, the infrastructure within Rajyaghar was vastly enhanced with thousands of miles of rail tracks being laid down throughout the colonial era. The ports were also improved to meet with euclean standards which further enhanced the trade prosperity of Rajyaghar. In a short period of time, the Rajyani economy was transformed and society had changed from a rural dominated one to a more suburban and urban one. Many historians now question the benefits of the infrastructure improvements with some arguing that it was overall beneficial to Rajyaghar and others arguing that it was only created to increase the speed at which natural resources could be taken out of Rajyaghar back to Euclea and to increase the profits of XX companies operating in the territory, not to further the economic growth of the local population.

Path to Independence

In the early 1900s, tensions between the great powers in Euclea continued to rise, requiring XX to withdraw more troops from the Rajyani territories to secure its mainland territories. Alongside this, tensions were continuing to rise between the lower rajyani classes and the colonial administration. As a result, the colonial administration was tasked with increasing the size of the Imperial Rajyani Territorial Army (IRTA) as well as taking over more duties from the Colonial Office in XX to deal with the rising territorial tensions. To facilitate this, Lord Cunningham, the Governor-General of Rajyaghar, summoned the Princes of the Princely States of Rajyaghar to the Imperial Palace in Kinadica. The meeting discussed Cunningham's plan to increase the size of the IRTA using the influence of the Rajyani Princes and Clan Leaders in return for increased self-governance. By the end of the three week meeting, a decision was agreed to in which the Rajyani leaders would use their influence to bolster the IRTA and in return they would form a National Council of Princes which would serve as the primary advisory council to the Governor-General. The deal would become known as the Cunningham Accords and were widely seen as a step in the right direction by the Rajyani people.

In 1926, the Great War broke out across Kylaris. Fearing a collapse of XX's colonial possessions, the newly installed Governor-General of Rajyaghar, Lord Maximillian Holmes, summoned a meeting of the National Council of Princes. Holmes called the meeting due to the fact that whilst the IRTA would be able to put up a fight against any invasion into XX Rajyaghar, it would not, at its current size, be able to play an offensive role in the Satrian theatre of the Great War. In response, the NCP assured Holmes that if he pledged to grant independence at the conclusion of the war, the NCP would help the colonial administration in its war. Holmes agreed to the measures on the condition that independence would be granted over a period of years after a period of self-governance under the supervision of XX. The measures were agreed to and the Holmes Plan was adopted. The response of the plan was more divided amongst the Rajyani people with the lower classes being openly against the agreement but with few economic opportunities and with princes still retaining significant cultural, political and religious influence, the IRTA expanded in size, securing the Rajyani Territories and its support in the Great War.

In 1929, the Government of XX fell and within a few days word reached the furthest corners of Rajyaghar and dissent and the idea of independence grew. Fearing a complete collapse of the Rajyani territories into civil war and with Great War still ongoing, Lord Holmes, who had since become an admirer of Rajyaghar, sought to ensure stability and order. As a result, Lord Holmes ordered no further offensives by the IRTA and recalled many regiments in order to ensure stability within the Rajyani Territories. Lord Holmes, a feirce royalist, also knew that the royal regime of XX was over and that he was now the highest ranking official in the Territories. Throughout his time as Governor-General, Lord Holmes had enjoyed warm relations with the tulyatan leadership who had always tried to remain friendly with the colonial administration to prevent punitive laws being introduced against the rajyani people, whilst the irfanic leaders had presented more of a problem due to their hopes of a seperate irfanic nation and their opposition to supporting the IRTA during the early 1900s and their later refusal to assist in its expansion for the Great War.

As talks of an early independence grew, fears began to grow within the tulyatan middle class and leadership over possible irfanic revolutions that could sweep to power an irfanic dominated government. Throughout the colonial era, the idea of a united Rajyaghar, which had never been considered prior, had become a unifying pillar in the resistance against colonial power particularly amongst the lower classes which did not identify as strongly with their princely states. Additionally, during the Great War, irfanic opposition to involvement had gained irfanic leaders popularity not only within their princely states but across Rajyaghar including within the tulyatan lower classes. As the idea of independence grew closer thanks to the Holmes Plan, the majority of the tulyatan population feared this growing irfanic popularity and so the tulyatan princes met with leaders of the tulyatan clans and reached an agreement. The agreement was based on the idea that an independent Rajyaghar would be a secular nation, so as to prevent an irfanic revolution against codified tulyatan dominance, but with a constitutional tulyatan monarch and elected government. The plan was put to Lord Holmes in February 1931 where he agreed to it. At the following meeting of the National Council of Princes in April 1931, Holmes presented the plan as if it was his own to reduce the likelihood of irfanic opposition. The irfanic princes, who had been fearing a presidential system plan in which the larger number of tulyatan states would be able to ensure no irfanic citizen became President, were surprised by the secular nature of the government and agreed to the plans. The agreement of the meeting also stated that independence would still only be given after the end of the Great War despite the collapse of the XX Government. In 1944 the agreement between the tulyatan leadership and Lord Holmes, which had previously been kept secret, became public knowledge and resulted in mass protests across the country which eventually subsided.

At a meeting of the National Council of Princes in January 1932, Prince Krishan III of the Princely State of Sanyukt was elected to be the first Maharaja of an independent Rajyaghar. The vote was almost unanimous with only a few Princes abstaining and none casting votes against. Krishan III is widely thought to have been chosen due to the dominance of the Sanyukti Empire pre-XX and due to his wide popularity amongst the tulyatan lower and middle classes, in part due to his public devotion to the tulyatan faith. Krishan III also had a record of welcoming and meeting with irfanic leaders for talks when religious tensions boiled over within the Princely State of Sanyukt, earning him favour with irfanic princes and leaders. At the same time, the new constitution was formally agreed to and it was announced that it would come into effect on the day of independence.

In February 1935, the Great War ended and the process of granting independence began. To ensure a smooth transition, elections to the new national parliament (Shahee Sansad) were called and the new members were elected in June 1935 but would not take up their seats until the day of independence. In Julu 1935, at a ceremony in front of the Imperial Palace, Lord Holmes signed the declaration of independence alongside Krishan III and marked the official end of colonial rule, the dissolution of the Rajyani Territories and the birth of the new Kingdom of Rajyaghar. In front of a crowd of over 500,000 people, Krishan III swore an oath of allegiance to the new Constitution, recieved the oaths of loyalty from the newly elected Shahee Sansad and formally swore in the first Government of Rajyaghar under the leadership of Prime Minister Pramod Ashtikar.

The Emergency

30 years after independence, religious hostilities culminated in open violence on the streets of the eastern union states. Protests and riots began across Rajyaghar due to conflicts between the Tulyatan Governments and communities in Irfanic dominated eastern states. The Irfanic communities were pushing for more representation in Union State Governments and the National Government as well as the introduction of their religious laws into Union State legislation. The latter worried the Tulyatan communities living in the Irfanic dominated eastern states and resulted in heightened tensions and openly hostile confrontations between the communities. In June 1965, opposing protests clashed in the city of Angara and on one monday, the protests turned violent resulting in the deaths of over three thousand civilians. The horrific event became known as 'Red Monday'. As a result the Prime Minister introduced a petition in the Shahee Sansad calling on the Maharaja to impose Martial Law, which the Shahee Sansad overwhelmingly voted in favour of. Two days after the petition was approved by the legislature, the Maharaja addressed the Shahee Sansad in person and announced the introduction of Martial Law and the granting of emergency constitutional powers to the Prime Minister.

Over the next two years, the Prime Minister would impose draconian measures in the eastern states under the guise of 'security, order and safety' for all Rajyanis and for Rajyani culture. The Government also lay the foundation for changes to the educational curriculum, the establishment of a domestic intelligence agency and the reorganisation of the police. Whilst originally very popular, the moves began to gain considerable opposition from within the Prime Minister's own party and in September 1967 the Prime Minister's own cabinet turned against him for going 'too far'. Many worried that the Prime Minister's plan for military governors to be installed in the eastern states risked civil war. In November 1967, the Prime Minister was defeated in a vote of no confidence and replaced by a Unity Government. In December 1967, the Maharaja formally ended Martial Law and withdrew emergency powers from the office of the Prime Minister at the request of the new Prime Minister and Shahee Sansad.

The Punaruddhaar

Geography

The geography of Rajyaghar is diverse; ranging from the Pavitra Valley in south-eastern Rajyaghar, to the Samara desert in Suit to the forested Laraca Hills in central Rajyaghar. Due to nature being considered sacred in the Tulyatan faith and nature playing a significant role in Rajyani culture, many of the natural landmarks of Rajyaghar are legally protected with many being National Parks.

Culture

Culturally, Rajyaghar can be split into two main groups; the tulyatans and pardarian irfanics. The East and South East of Rajyaghar is dominated by the irfan communities whereas the west is dominated by the tulyatan communities. Whilst the nation is split 60:40 in terms of land area dominated by Tulyatan communities and Irfan communities respectively, in terms of population size the tulyatan community is much larger with there being a 70:30 divide. As a result, much of the national government is tulyatan dominated, a result of this demographic situation and the historical events that led to independence.

Clans

In modern Rajyaghar, the historical clans of the past still have considerable influence. During the Vikasan era, when the Middle Kingdoms of Rajyaghar were being formed, clans retained their clan structures and the new Kingdoms and Empires would become collections of clans rather than merging clans together. In modern Rajyaghar, Clans have become societal groups with people of the same Clan often being from the same religious predisposition and living in the same states and cities. Most Clans have also retained their leading families which has resulted in the leaders of the Clans maintaining incredible influence within Rajyani society. As a result of this, the leaders of all of the recognised clans of Bharatt (78 in total) are granted seats in the Shahee Sansad to represent their members who may be spread across multiple Shahee Sansad elected constituencies.

Throughout Rajyani history, numerous clans would be part of a single Kingdom and as such, no clan would exist in more than one kingdom. When Kingdoms expanded, clans would either gain or lose territory, rather than a part of the territory being part of one kingdom and another being part of another kingdom. There would also be migration of individuals into their new territories or away from lost ones. Clan Leaders would often make up advisory councils for their Kingdom's Maharaja and even in modern day Rajyaghar, Clan Leaders still form advisory councils to the successors of the Maharajas of the Middle Kingdoms; the Union State Princes.

Politics and Government

Maharaja

Prime Minister

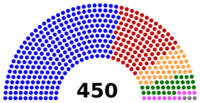

Rajyaghar has been a federal, constitutional monarchy since 1953. Whilst the Constitution grants significant powers to the Maharaja, over the decades following independence, much of the power granted to the Maharaja has been exercised by the Premier of Rajyaghar (officially called the Peshwa). The Constitution also set out the creation of an independent judiciary appointed by the Maharaja and a Shahee Sansad which maintained budgetary control. The nation’s executive government is led by the Maharaja who appoints a Peshwa (i.e. Prime Minister) who in turn nominates individuals to the Maharaja to serve as Government Ministers in the executive government, called the Central Union Government. The Peshwa is appointed by the Maharaja and is often the leader of the largest party or coalition in the Shahee Sansad. The legislature is the Shahee Sansad and is a unicameral legislature consisting of a mix of appointed and elected representatives. The Chamber has 450 directly elected constituent representatives, 78 appointed representatives (by the Maharaja) and 112 Clan Leaders. Legislation passed by the Shahee Sansad must be granted assent by the Maharaja. A veto cannot be overridden.

There is also a National Council of Rulers which consists of the former Maharajas of the pre-colonial kingdoms of Rajyaghar; who are now granted the title of ‘Prince of the Union State of [union state]’. To distinguish between these Princes of the former kingdoms and the Royal Princes from the reigning family, the former Kingdom princes are called "Union State Princes" and royal princes are "Princes of Rajyaghar". Similarly, Union State Princes have the prefix of "Highness" whereas Royal Princes have the prefix of "Royal Highness". The Council of Rulers is an advisory council to the Maharaja and is often summoned for advice on constitutional crises or other matters of national importance, to provide non-political advice to the Maharaja. During events of national significance, such as the coronation of a new Maharaja, the Council of Rulers plays a key ceremonial role; i.e. at the Durbar following the coronation where all of the Princes pledge allegiance to the new Maharajas.

All branches of government, including the Monarchy, Shahee Sansad, Executive and Supreme Court, are found on Government Hill in the capital of Kinadica.

Government

Rajyaghar is a federation with a parliamentary system governed under the 'Soveriegn Constitution of the Kingdom of Rajyaghar', the supreme legal document. Rajyaghar is a constitutional monarchy and representative democracy, in which the Maharaja "serves to protect Rajyani culture, democracy and sovereignty". Federalism in Rajyaghar is defined as the delegation of authority and responsibility from the Union Government to the Union States of the Kingdom. Rajyaghar's form of government, was traditionally described as 'federal' with a moderate central union government and strong states, but since independence there has been a slow progression from a true 'federal' system to a 'quasi-federal' system in which modern Rajyaghar operates a strong central union government and weak states.

The national government of Rajyaghar is split into three branches with the Maharaja serving as the head of each but, through the constitution, has delegated authority to constitutionally described officers.

|

National Party (Government) Cooperative Party (Official Opposition) Liberal Party Irfanic Coalition Tarkhana National Party Independents |

- The Executive - Central Union Government - This is the executive arm of the Government of Rajyaghar and is made up of Union Secretaries of State and Union Ministers of State. The Cabinet is the executive committee of the Central Union Government and is led by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is appointed by the Maharaja provided the candidate can command a majority in the Shahee Sansad (legislature). Any of the Union Secretaries and Ministers that hold a portfolio must be a member of the Shahee Sansad in order to ensure parliamentary accountability as the Prime Minister and Cabinet are directly responsible to the Shahee Sansad. Civil servants act as permanent executives and all decisions made by the Cabinet are enacted by the Civil Service.

- The Legislature - Shahee Sansad - The Shahee Sansad is the national legislature for the Kingdom of Rajyaghar and is tasked with creating, amending and repealing legislation and laws which are then presented to the Maharaja for assent or veto. The Shahee Sansad is presided over by the Speaker who is nominated by the Shahee Sansad, and then appointed by the Maharaja, and is required to be impartial. The Shahee Sansad consists of 450 members; 300 representing the constituencies of Rajyaghar, 122 leaders of the registered Clans and 78 appointed by the Maharaja. The Constitution grants the Maharaja the right to open and close the Shahee Sansad at their discretion but it does prevent any term of the Shahee Sansad from lasting more than 5 years. This allows for hung parliaments to be dissolved and new parliaments to be elected in order to ensure government work continues. Since 1995, elections have been held regularly every 5 years.

- The Judiciary - The Kingdom of Rajyaghar has a multi-tiered independent judiciary consisting of the Supreme Court, headed by the Lord Chief Justice, 28 State High Courts, a large number of Crown Courts and an even larger number of Clan (Civil) and Magistrate (Criminal) Courts. Whilst the Supreme Court is the highest Court in the land, appeals of Supreme Court decisions may be taken up by the Privy Council of Rajyaghar at the discretion of the Maharaja. Justices of the Supreme Court and State High Courts are appointed by the Maharaja on the advice of the Independent Judicial Appointments Commission (IJAC) whilst Crown and Magistrate Court judges are appointed by Union State Princes, on the advice of the IJAC, and Clan Court judges are appointed by Clan leaders.

Administrative Divisions

Rajyaghar is a federal union comprising of 25 Union States and the Capitol District. All of the states and the Capitol District have elected executives and legislatures which follow the Northabbey model of governance ass laid out by the Constitution. In 1978, the Rural Governance Act reorganised the local governments of rural areas on a clan basis. As a result, rural constituencies to the Union State legislatures and national legislature follow clan borders and Clan (civil) and Magistrate (criminal) court jurisdictions match those of clan borders in rural areas.

In 1965, at the beginning of 'The Emergency', the 12th Amendment was added to the Constitution. The amendment grants the Maharaja the explicit right to suspend a Union State's legislature and executive governemnts, either individually or together, and replace them with a Governor and Union State Council appointed by the Maharaja to deal with executive and legislative functions. The amendment states that the Maharaja can only exercise this right on the advice of the Central Union Government and that the Shahee Sansad (national legislature) can overturn this action by a simple majority. The amendment has been invoked multiple times since the emergency in order to deala with hung union state legislatures in times of political crisis. All invocations have been widely supported across party lines as it has now become tradition that the Prime Minister will only ask the Maharaja to invoke the 12th amendment if it is supported by the Shahee Sansad.

| Swarupnagar | Nakhtrana | Raulia | Sasipur | Pinjar |

| Rathankot | Dedha | Chanak | Sanosra | Suti |

| Kodur | Bhankari | Zulmat | Lakhana | Parsa |

| Dharana | Mondari | Samara | Sanyukt | Bishnupur |

| Harringhata | Tarkhana | Bandra | Dalar Bewar | Sangam |