Valduvian Reaction

The Valduvian Reaction, alternatively referred to as the Valduvian Correction, Valduvian Reformation, or Valduvian Schism, was a Sotirian religious and political movement in the Platavian Union and parts of the Rudolphine Confederation during the 16th century. Usually characterized as part of the broader Amendist Reaction, the movement saw the spread of Kausian theology throughout modern-day Valduvia and culminated in the ongoing break in communion between the Valduvian Apostolic Church and the Solarian Catholic Church. The movement's description as Amendist is controversial among scholars, and a sizable minority argue that the theological basis for the events in question is more closely related to Episemialist theology than that of other contemporary Amendist movements. For this reason, the Valduvian Reaction is sometimes considered to be a distinct event drawing inspiration from the zeal of Amendist reformers, rather than a constituent movement of the latter.

The Valduvian Reaction began in 1515 when Arvīds Kauss, the Archbishop of Matīspils, delivered his Letter of Grave Concern to Pope Caritas IX. In his letter, Kauss expressed consternation over the excommunication and killing of leading reformer Johanne Stearn that had occurred several months prior, and outlined several teachings and practices of the Catholic Church that Kauss argued were recent inventions inconsistent with historical Sotirianity. Kauss's points included critiques of papal supremacy, clerical celibacy, the distinction between mortal and venial sins, indulgences, the concept of purgatory, closed communion, Filioque, the relationship and relative authority of scripture and sacred tradition, and Catholicism's claim to be the one true church. Kauss gained a significant following among the Platavian clergy and was openly supported by King Matīss IX, who promoted the spread of Kausian theology in neighboring Burland with the aim of undermining Rudolphine authority in the region. The Solarian Catholic Church ultimately repudiated Kauss's views at the Council of X in 15XX, and Kauss and his followers were excommunicated. The prelates of the Burish churches subsequently established full communion with Matīspils in 15XX, leading to the formation of the Valduvian Apostolic Church and marking the end of the Reaction.

The effects of the Reaction were widespread, with religious, societal, and political ramifications that permanently shaped the course of Valduvian history and that of Euclea as a whole. The movement resulted in Kausianism, specifically in its institutionalized form under the Valduvian Apostolic Church, emerging as the dominant Sotirian tradition in the territories of modern-day Valduvia. Kausian concepts such as scriptura per traditionem and branch theory formed the basis for a new theological paradigm in Eastern Sotirianity, distinct from both Catholicism and most other strains of Amendism. The status of Kausian Sotirians in Burland was a significant cause of the Amendist Wars during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, with the Platavian Union intervening to protect the rights of Amendists in the Rudolphine Confederation. Platavia and the Burish states subsequently formed the Valduvian Confederation, the earliest predecessor of the modern Valduvian state, as a defensive bulwark against future aggression by the Rudolphines. The shared religious identity between Burlanders and ethnic Valduvians would later become central to the emergence of a Valduvian national identity in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Nomenclature

Background

The region surrounding the Valduve River has occupied a unique position in the Euclean religious landscape since its Sotirianization during the early medieval period. Although formally under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Solaria and thus ecclesiastically tied to Eastern Sotirianity, Sotirians in medieval Valduvia were heavily influenced by Western theology due to their geographic location at the western frontier of the Solarian Catholic Church. Local church leaders frequently sided with the western patriarchs in theological disputes, but still submitted to Solaria's ecclesiastical authority. Valduvia ultimately remained under the jurisdiction of the Papacy following the Lesser Schism of 1385, which led to a break in communion between the Solarian Catholic and the Episemialist churches. Nevertheless, the Valduvian church continued to preach many theological doctrines that set them at odds with Solaria, including the rejection of the Filioque, the distinction between mortal and venial sins, and the Eastern interpretation of purgatory. Liturgically, the Valduvian church eschewed the Solarian liturgical rites in favor of the Valduvian Rite, a unique ritual family using the Church Platavian language.

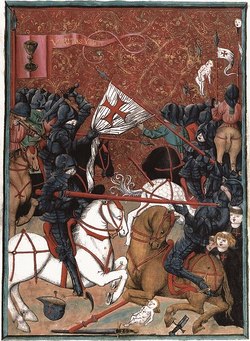

Nevertheless, the Valduvian church maintained cordial ties with Solaria until the rise of the Pelšite movement during the 1440s. The Pelšites, a group of radical proto-Amendists which preached an extreme form of apostolic poverty and rejected clerical celibacy, found fertile ground for their ideas in an environment already disillusioned with the state of the Solarian Catholic Church. The movement spread rapidly as a consequence, with the both the nobility and clergy in the southern Valduvian states of Vējstāda, Ābeļpils, and Mežmalas embracing the Pelšite tradition. In order to suppress what Solaria viewed as a heretical movement, Pope Alexander IX appealed to Jānis IV, the staunchly Catholic King of Platavia, for military assistance. Seeing an opportunity to both win the favor of Solaria and establish dominance over his geopolitical rivals, Jānis sent his armies south to crush the dissident sect. Jānis defeated the renegade states in a matter of months, effectively destroying the Pelšites as a significant religious movement and establishing the Kingdom of Platavia as the dominant military power west of the Valduve.

In order to prevent future division in the aftermath of the Pelšite movement, the Papacy expanded the ecclesiastical province of the Archdiocese of Matīspils to include all of the territories west of the Valduve River and north of Gaullica. This measure effectively vested Matīspils with primacy over the entirety of the Valduvian church, where previously its authority was confined solely to Platavia. Solaria hoped that empowering the traditionally loyal Platavian church would allow for future dissident movements to be extinguished in the cradle and promote uniformity of belief with the rest of the Catholic world. However, this consolidation of power also had the unintended effect of elevating Matīspils to the point where its authority was perceived by the laity as rivaling that of Solaria itself. The new province was far larger, wealthier, and more populous than any other ecclesiastical province within the Catholic Church, making the Valduvian prelate one of the most powerful religious leaders in Eastern Euclea. Numerous writings from contemporary religious and political figures refer to the Archbishop of Matīspils as the "Little Pope" or the "Valduvian Pope", reflecting the unusually high esteem which the office conferred upon its holder. By the early 16th century, it was common for political leaders in the Valduvian states to seek the opinion and approval of Matīspils before that of the Pope when making decisions.

Events

Letter of Grave Concern

At the beginning of the Amendist Reaction, many Valduvian Sotirians saw their disputes with the Papacy as analogous to those of the Eastern reformers. Unlike in Estmere and the Rudolphine Confederation, the church leadership in the Valduvian states was largely sympathetic to the Amendist cause. The incumbent Archbishop of Matīspils, Arvīds Kauss, had been a significant proponent of reform in the Catholic Church for several years prior to the Reaction and made a number of supportive public statements regarding Amendist leader Johanne Stearn. However, Kauss also vocally disagreed with many of Stearn's theological positions and even published a rebuttal to several of his key arguments. Kauss took particular issue with Stearn's five solae, which he argued were oversimplifications of critical doctrine that ignored important nuances. Due to these theological differences, Matīspils did not formally support the Pilgrimage of Humility despite the direct involvement of numerous individual priests under its jurisdiction. Kauss nevertheless continued to speak favorably about the reformers themselves, and urged Pope Caritas IX to convoke an ecumenical council to deliberate on their concerns.