Dzhungestan

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Republic of Dzhungestan Бүгд Найрамдах Зүүнгар Улс Bugd Naĭramdakh Züüngar Uls | |

|---|---|

| Capital and | Dörözamyn |

| Official languages | Dzungar |

| Ethnic groups (2016) |

|

| Religion | |

| Demonym(s) | Dzhungestani; Dzungar |

| Government | Federal republic |

• President | Besud Bogarji |

| Legislature | Great Assembly |

| Area | |

• land only | 1,920,397.5 km2 (741,469.6 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 4,031,247 |

• Density | 2.10/km2 (5.4/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $19.886 billion |

• Per capita | $4,934 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $9.323 billion |

• Per capita | $2,313 |

| Gini (2015) | 42.5 medium |

| HDI (2014) | high |

| Currency | Tögrög (DZT) |

| Time zone | SST+6 |

| Date format | yyyy.mm.dd (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +942 |

| Internet TLD | .dz |

Dzhungestan (Dzungar: Зүүнгар Улс, pr. Züüngar Uls), officially known as the Republic of Dzhungestan (Бүгд Найрамдах Зүүнгар Улс, Bugd Naĭramdakh Züüngar Uls) is a sovereign state in Septentrion. It is the only landlocked country on the continent of Hemithea, bordering the states of Polvokia, Menghe, Maverica, and Themiclesia. Despite having a vast land area, it is home to only 4.03 million people, as the country spans desert and steppe with little arable land. Historically, most of the population was nomadic, and nomads still make up 20% of the population.

Etymology

Dzhungestan is named after the Dzungar people, who make up most of the population and historically ruled the country from a central khanate. This demonym is derived from Züün Gar, or "Left hand," as according to legend the Dzungar trace their ancestry to a branch of a tribe which was seated on the left wing of the Great Khan's yurt.

In the Dzungar language, Dzhungestan is known only as Züüngar Uls; the suffix "-stan" was added by Casaterran geographers in the 19th century, and remains standard in English-language sources, though it has no basis in the country's native tongue. Prior to that time, its name in Tyrannian was Zungaria, a term which is sometimes used today but does not enjoy official status.

History

Antiquity

Middle ages

Great Dzungar Khanate

After the Menghean Black Plague topped Menghe's Ŭi Dynasty, the main threat to the remaining northern tribes receded, creating a power vacuum in central Hemithea. The plague itself appears to have barely reached Dzhungestan. Under the leadership of Baydar Khan, the Dzungar tribe managed to unite a broad swath of land in the center of Hemithea, forming the Great Dzungar Khanate in 1542. Today, Baydar Khan is considered by many to be the father of the Dzhungestani nation.

Baydar Khan adopted a few ruling methods from Menghe, establishing a stationary capital at Dörözamyn and hiring administrative officials based on merit - though locally, this was interpreted as merit in battle and, later, in hunting. At the same time, he retained many country's nomadic traditions in the countryside.

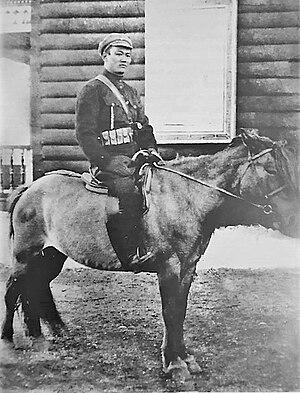

Dzungar horsemen, who by the mid-19th century had adopted homemade muskets in addition to the bow and arrow, remained a formidable force on the empty steppe, where scarce supplies, long distances, and cold temperatures made it difficult for foreign armies to field cannons or seek a decisive battle. After a series of unsuccessful military expeditions into the interior, Polvokia, then a Letnevian colony, recognized the Great Dzungar Khanate as a sovereign entity in 1864 and negotiated a series of treaties clarifying their borders; Themiclesia soon followed suit.

In 1923, the 17-year-old Batzorig inherited the title of Khan. Intent on modernizing the Great Dzungar Khanate, he tacitly authorized a series of mounted militia raids across the Themiclesian border near Yaamdarga, hoping to bring the area's rich copper mines under Dzungar control. While initially successful, this plan soon backfired, forcing Batzorig and his aides to flee to the countryside as two Themiclesian motorized divisions drove toward the capital. With the help of Menghean arms, volunteers, and aircraft, Batzorig was able to return to Dörözamyn in 1933. For the remainder of the Pan-Septentrion War, the Great Dzungar Khanate remained a key logistical conduit from Menghe to Themiclesia, and contributed cavalry units to the Menghean offensive.

At the end of the war, the Allied Occupation Authority decided to pass power to Negübei Khan, a nephew of Batzorig who had fled to Themiclesia in 1921 out of a fear that he would be put to death as a potential rival for the throne. By 1946, he was old and liberal-minded, and the Allies decided he would make a trustworthy ally once in power.

Mid-20th century to present

Negübei Khan pursued some modernizing and liberalizing policies while in power, but his reign was marred by his lack of interest in political affairs. His grandson Toghemur, who succeeded him in 1952, was particularly corrupt and unpopular, and soon gained a reputation as a shameless womanizer. Exploiting the Khan's lack of popularity, Communist-aligned militants began raiding villages in the east, arming themselves with weapons supplied by Polvokia and later Maverica. The Communist insurgency picked up in 1962, as the Menghean War of Liberation spilled over the border and Communists cut off the land route south to the GA-friendly Republic of Menghe.

These militants maintained only a minor presence until 1973, when Sim Jin-hwan dispatched a mechanized force across the border to "stabilize the situation." This resulted in the creation of a Communist and Menghean-backed state in the south, known as the People's Republic of Dzhungestan. It also resulted in the integration or expulsion of Maverican-backed militants in the southwest. Toghemur Khan's forces retreated to the north, where they received additional support from Themiclesia and the Organized States, leading to concerns that Menghean and Columbian ground forces would encounter one another in the proxy war and set off a major military conflict.

To disarm the situation, Columbian diplomats secretly flew to Sunju in 1975, where they held a covert meeting with their Menghean counterparts and agreed to partition the country between a People's Republic of Dzhungestan in the southeast and a Khanate of Dzhungestan in the northwest. The border, which only ever existed on paper and was never enforced on land, ran across the arid heart of the Central Hemithean Steppe, which served as a buffer zone between the two regimes. The DPRM withdrew most of its troops from the country, as did the GA.

After the peace agreement was signed, the GA pressured Toghemur's successor, Ogtbish Khan, to resign and open the way for democratic reforms. Elections were held in 1978, and a new constitution was promulgated in 1981, with an elected president in place of a Khan. The new government promoted modernizing reforms and economic development, reforming the education system and opening the way for investment by Themiclesian and Columbian corporations. To the southwest, the People's Republic of Dzhungestan attempted to rapidly modernize the country by following the Menghean model, forcibly resettling nomadic tribes onto sedentary agricultural communes and setting up state-owned mines and cotton plantations. These efforts were deeply unpopular, and left the regime dependent on secret police and Menghean troops to stay in power.

Regime change in Menghe and the Ketchvan insurgency in Polvokia removed the PRD's only real allies, leaving it geopolitically isolated. Menghe withdrew its troops from the country in 1989, after abolishing their regime maintenance mission the year before. Faced with major protests in the cities and the threat of insurgency in the countryside, Premier Marks Ketboge announced in 1991 that he would allow the free election of a transitional government. With advisory support from Columbia, Themiclesia, and Menghe, the two Dzhungestans were reunified into one state, the Republic of Dzhungestan, in 1993, under a new federal constitution.

Geography and climate

Government and politics

Dzhungestan is a federal representative democracy with a directly elected president and a unicameral legislature. The current constitution, ratified in 1993, provides for fair elections and a range of personal freedoms, and has resulted in a thriving multi-party democracy. Dzungar Khoridai, the son of Ogtbish, holds the ceremonial title of Khan, and his eldest son Torbiashi is crown prince, but in contrast to a constitutional monarchy, the Khan is a purely informal position and members of his family are barred from involvement in politics.

Since reunification, there have been three main political parties in Dzhuntestan. The center-left Democratic Party (Ardchilsan Nam), which oversaw the transition to a unified state, has dominated the political scene, holding the presidency from 1993 to 2005 and again from 2009 to 2013. The center-right Liberal Party (Liberal Nam) ruled from 2005 to 2009 and has held the presidency since 2013 after reorganizing into the Unity Party (Ev Negdel Nam). The far-left Socialist People's Party (Sotsialist Ardīn Nam), staffed by former cadres of the People's Republic of Dzhungestan, played a prominent role in the opposition during the 1990s, but its support has dwindled, and it currently holds only a single seat in the 97-member legislature.

The president holds considerable power in Dzhungestan's unitary system, a phenomenon which some have attributed to cultural expectations of a strong ruler and others see as a necessity for holding together a large and underdeveloped country. Both leading parties are fairly democratic in their orientation, with professed support for the 1993 constitution and its guarantees for personal freedoms, and apart from the Socialist People's Party, no far-left or far-right parties are represented in the legislature. Yet increasing trade with Menghe has led to growing financial influence from large mining enterprises, especially Menghean ones. Critics of President Besud Bogarji have accused him of embracing the "Menghean model" of a strong executive who favors economic development over human rights, though the Democratic Party has also remained mute on issues of labor rights and environmental protection.

Economy

With a GDP (PPP) per capita of $4,934, Dzhungestan is the poorest country on the continent of Hemithea. Historically, a widely scattered population, a shortage of arable land, and the lack of a coastline for trade hindered its development, as did a series of self-imposed isolationist policies. Since the 1990s, however, this situation has started to change; foreign investment and improved railroad infrastructure have generated a modest economic boom. Annual GDP growth averaged 9.2% between 2008 and 2018, though this growth was unequally distributed across the country.

Mining has emerged as the largest economic sector in the country, followed by natural gas and cotton. The large primary sector is fed by recent economic growth in Menghe, where rapid industrialization has brought a surge in demand for natural resources. Indeed, Menghe represents both the largest destination for Dzhungestani exports and the country's main source of FDI, as Menghean companies invest in expanding mining facilities and transportation infrastructure. In 2010 Dzhungestan joined the Central Hemithean Economic Community with Menghe and Polvokia, and in 2019 it will join the Trans-Hemithean Economics and Trade Association as one of the seven founding members.

Herding also remains economically significant, if only because it covers a wide area unsuitable for farming. Roughly one-fifth of the population is estimated to be nomadic, still engaging in the traditional herding of cattle, sheep, and horses for subsistence and trade. Exact numbers are disputed, as it has become common for sons of nomadic families to seek work in the cities and towns while sending remittances to their relatives. Nevertheless, despite its small proportion of GDP, nomadic herding accounts for a large share of Dzhungestani employment and remains a central representation of the national lifestyle.

While rapid growth has helped lift much of the population out of rural subsistence poverty, it has also had serious destabilizing consequences for Dzhungestani society. Much of the growth has been concentrated in cities and towns, where new migrant workers live in shantytown housing. Labor safety regulations are notoriously poor, especially in small independent mines, and wages remain very low. The influx of cheap manufactured products and consumer goods from Menghe has also steeply undercut what remained of Dzhungestan's industrial sector, and most Dzhungestani heavy industry is focused on the processing of ore from nearby mines. Menghean companies in Dzhungestan have been criticized for bringing in Menghean engineers and management staff, denying locals the best-paid jobs; the Menghean government agreed to encourage the hiring of local workers under the THETA negotiations.

Military

Foreign relations

Demographics

Culture

Names

For much of history, it was customary in Dzhungestan to assign children only a given name; there was no surname or patronymic carried down across generations. Thus, historical Khans like Batzorig and Negübei are known exclusively by their given names.

The tradition of adding surnames began in the late 1970s, as part of the People's Republic of Dzhungestan's effort to modernize the country and improve the reliability of government records. The ruling Communist Party decided to follow the Menghean model, requiring families to adopt patrilineal surnames which precede the given name. In cases where citizens refused or were unaware, census-takers assigned names to them based on their job or area of residence. Other families adopted names referring to historical clans, tribes, and Khanates, or changed their assigned names to these after democratization in 1993.

Today, most ethnic Dzungar only use their given names in everyday contexts. In formal or business contexts, a person named Borjigin Jeder would be addressed as Jeder guai or "Mr. Jeder," even though Jeder is the given name and Borjigin is the surname. Surnames mainly appear on government documents, such as passports and marriage certificates.