Fahran

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Second Gharib Republic of Fahran Jumhuriyyah al-Gheiravyat al-Thaniyyah al-Fahraaniyyah (Gharbaic) | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

Motto: "Ma zal lahabna yahtariq" "Our flame still burns" | |

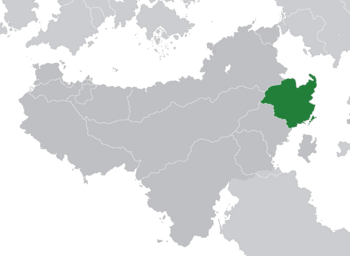

Location of Fahran (dark green) | |

Political Map of Fahran | |

| Capital | Haqara |

| Largest city | Qhor as-Sadaf |

| Official languages | Gharbaic |

| Recognised regional languages | Nimanheric |

| Ethnic groups | Gharbiyyun (91.51%) Nimanis (4.84%) Karduenes (0.63%) Other (3.02%) |

| Demonym(s) | Fahrani, Gharib |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic |

• President | Mohammed Sabbagh (al-Wahda) |

• Prime Minister | Ali al-Quwwas (al-Wahda) |

| Legislature | Majlis |

| Establishment | |

| 1066 CE | |

| 1571 CE | |

| 1835 CE | |

| Area | |

• Total | 665,216 km2 (256,841 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 1 |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 35,084,331 |

• 2010 census | 31,316,864 |

• Density | 52.74/km2 (136.6/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $422.6 billion (x) |

• Per capita | $13,495 |

| Gini (2010) | 53.9 high · x |

| HDI (2015) | high |

| Currency | Riyyal (RYL) |

| Time zone | UTCx (x) |

| Date format | dd ˘ mm ˘ yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +1121 |

| Internet TLD | .frn |

Fahran (Gharbaic: al-Fahraan) officially the Second Gharib Republic of Fahran (Gharbaic: Jumhuriyyah al-Gharibyat al-Thaniyyah al-Fahraaniyyah), is a Gharib sovereign state and semi-presidential unitary republic situated in eastern Scipia. Fahran occupies 527,015.78 km2, including both its mainland territories and the Nalmorian Archipelago. It borders Charnea to the west, the disputed territory of Happara to the northwest, Vardana to the north, the Ozeros Sea to the east, and Kembesa to the south. Fahran comprises seven provinces and thirty four governates. The capital is Haqara. The largest city is Qhor as-Sadaf. Fahran numbers among the most ethnically and racially diverse countries in the region and is home to Gharbiyyun, Nimanis, and Karduenes, as well as smaller populations of Janubis and Qafáris. Around 88% of the country's 35 million citizens are Yen, with Fabrian Christians, Orthodox Christians, Jews, and non-religious people making up small but significant minorities, especially in the large coastal cities. The sole official language is Gharbaic, though regional languages have been nominally recognized since the December Intifada and the ratification of the 1996 Constitution.

Fahran possesses a comparatively short but historically important coastline, encompassing the Strait of Sabatha, the Nalmorian Archipelago, and the Gulf of Yamtar, which allowed it to play a pivotal role in the spice and incense trades until the late medieval period. While much of its terrain is dominated by semi-arid plains, sandy deserts, and seasonal wadis, the River Aynúr with its numerous tributaries, located in northern Nimanher, and the River Fénya, located in southern Nimanher, create alluvial flood plains. Aquifers and underground springs play a similarly important role, often serving as the life blood of oases, and support many of the most populous cities of Fahran. Fahran is divided by the interior Zabalan Mountains, which rise up from the hills of western Amran to the east extend towards Ramlat Abu al-Dhiyb Desert to the west. The varied and often harsh terrain of the country has left a profound imprint on the peoples who inhabit it.

Fahran is a developing country. Since the tenure of President Ali Adnan al-Sharif, who was indicted for and convicted of charges of corruption, money-laundering, and misappropriation of public revenues in 2016, Fahran has often been described as a kleptocracy or a plutocracy, and has consistently numbered among the most corrupt countries in the world. In the absence of well-developed civilian institutions, elite-oriented politics has constituted a de facto form of collaborative governance, with competing tribal, religious, and political factions agreeing to hold themselves in check through implicit acknowledgement of the balance of power. This system was largely bolstered and upheld by the role of the military, under the nominal command of retired Field Marshal Cebrail Osman al-Nerraphne, as the guardian of the republic. A unique form of politicking based on extended kinship networks and extensive patronage has dominated the country since the early modern period, feeding into the deep-rooted corruption. The recent election of President Mohammed Sabbagh and Azdarin Unity has suggested the end of power sharing between elitist interest groups and the advent of popular democracy in the Azdarist mold.

Culturally, Fahran has a rich heritage and celebrates the achievements of its past in both pre-Yen as well as post-Yen times. It is well-known for its poetry, including such epics as the Epic of Barsalan, the Aydhariadh, and the Lament of Qasim and Izgadhil, and its finely crafted weapons and jewelry, often making use of gold, pearls, and ivory. Its architecture is among the most renowned in the Yen world and is reflected by a great many palaces, gardens, and shrines erected in the elegant style of the Age of Pearls.

Etymology

The Gharbaic name al-Fahraan first appears in the El Haddah Manuscript, dated to around 352 BCE, where it referred to a region encompassing modern Yamtar and 'Amran provinces. It's etymology is derived from the Old Fahranic word fahrih, meaning "blissful" or "paradise", as the country was well-known in antiquity for its vineyards and fertile soil during the rainy season. This is in contrast for the name Radhayaan, used to describe the more arid geographical range in what is now the Hasidhmawt. By the reign of Ramil-Qahirnisat II, the name had come to apply to all lands east of and including the Ramlat Abu al-Dhiyb Desert, with the Latins referring to the geographical area and cultural sphere as Garabia Felix.

Following the completion of the Eidrusid Conquest in 1571 CE, it became customary for Belisarians to refer to subjects of the Eidrusid Sultanate as Fahrani in the singular and Fahranis in the plural, with Fahrani also serving as the adjective to describe things relating to the country. These conventions only became popular in Fahran itself following their explicit introduction towards the middle of the Tajdid Era, specifically during the reign of Sabah I. Fahrani constitutes both an ethnonym and a demonym, and, while it theoretically applies to non-Gharib subjects of the country, most non-Gharibs self-identify based on their own local ethnonyms and demonyms. The older adjective Fahranic occasionally appears in popular parlance, though it's more generally restricted to discussions of pre-Yen cultures, pre-Gharbaic languages, and national epics like the Aydhariadh.

The majority of the people who inhabit modern Fahran are part of a broader linguistic and ethnic community known as the Gharbiyyun. The word gharib is derived from an Old Lysanic root meaning "western" or "westernesse", alluding to their ancestral homeland farther west in Scipia. It is often used interchangeably with Fahrani in describing the citizens of Fahran, though, notably, this doesn't apply to ethnic minorities who tend to prefer their own ethnonyms.

History

Prehistory

Between 52,000 BCE and 41,000 BCE, the hypothetically fertile Falaqan Valley could have played home to a collection of Paleolithic cultures, the remains of which have been uncovered as far south as the Gap of Sawad. This region is likewise the location of a cluster of primitive communal cave burials, dating from approximately 11,000 BCE, which provide the earliest direct evidence for modern humans in the region.

Organized, permanent human habitation in Fahran occurred as early as 5,400 BCE, with widespread evidence of animal husbandry, especially of goats, sheep, and dogs. Archaelogical finds in the form of stone tools, statuettes, and ceremonial burials that yielded human and animal skeletons attest to the increasing complexity of the material culture of the local inhabitants. This collection of sites has been collectively referred to as the Sawad Neolithic A culture. These discoveries reflect the significance of the sites as an important step in the development of ancient civilization and give it significant prehistoric importance with enough proof and detailed data to rewrite the Neolithic history of Eastern Scipia. The Sawad Neolithic A culture also reveals additional information about the relationship between human economic activities and inherent climate change, how hunter-gatherer societies became sedentary, how they made use of natural resources available to them, and how they set in motion the domestication of plants and animals.

The succeeding Sawad Neolithic B and Dismaya cultures demonstrate ever-increasing levels of advancement in agriculture, tool-making, and even alleged proto-writing in the form of the Hiswan Script, collections of intricate symbols scrawled on turtle shells or clay tablets uncovered in and around the modern governate of Helarun. Some linguists have cast doubts regarding the viability of the Hiswan Script as a form of proto-writing due to the ostensible randomness of the geometric shapes documented and the absence of a coherent link to any surviving written language. The Sawad Neolithic B culture persisted from 4,800 BCE to around 3,900 BCE, briefly overlapping with the Dismaya culture which spanned a period stretching from 4,200 BCE to 3,500 BCE. The Erakkûr Civilization, which began in 3,400 BCE and survived until 2,980 BCE, continued these trends while presenting archaeologists with the first verifiable examples of standing, monumental architecture. A notable absence of decipherable written records from this period has left archaeologists and linguists stumped regarding the languages spoken by these early civilizations, though some theories have postulated that their language was Iranian or Semitic in origin. Others have argued that it was an isolate that became extinct after the Rhûnyic Migrations into the region around 2,900 BCE.

Bronze Age

The earliest historic culture in Fahran dates back to the Tel Gezir Period, which began around 2800 BCE. Compelling evidence of complex civilization exists in the form of pottery shards, clay tablets, temples, and ritualistic catacombs called mastabas scattered around sites near the modern city of Qhor am-Sadf. While some experts have argued that Barseh, a site located in the southern coast of Yamtar, near modern Fatima, would have been more hospitable to an early civilization, the archaeological record has yet to yield substantive evidence of habitation there prior to 2,700 BCE. The settlements in mainland Fahran likely belonged to the broader Rhûnya Culture, which had migrated from their ancestral homeland in what is now Kardistan. One of the oldest recorded myths, the Epic of Barsalan, was put down in writing during this period. Its contents and themes suggest that institutions such as kingship, the priesthood, and a rigid caste system had become formalized across a multitude of independent but economically intertwined city-states.

By the early Bronze Age, circa 2400 BCE, large polities such as Sai, Umma, Kšayr, Sidura, and Birzana had formed intricate and expansive commercial networks. Sai, the most powerful of these early city states, exerted suzerainty over a number of the burgeoning settlements that had cropped up along the Straits of Sabatha. It's ruined capitol at Aaxo-Menhet, based on the island of al-Bahriyyah in the Nalmorian Archipelago, has yielded extravagant palatial complexes and the remnants of what would have been the largest harbor in the world at the time. Sidura, on the other hand, was the most prominent of the mainland city states, occasionally exerting hegemony over Umma and much smaller hamlets. The middle of the Bronze Age saw increasing violence and tumult across the region, reflecting the jockeying that occurred between disparate polities and tribes, who often spoke unique dialects and worshiped deities particular to their locality, for dominance. These conflicts culminated in the ascendancy of Ilarin on the mainland and the trade-power of Qaraax in the Nalmorian Archipelago.

According the Annals of the Rhûnyic Kings, a semi-historical chronicle detailing the lives and deeds of the priest-kings of Anšan, Ahru-Nunamnir established what would become the administrative and cultural capital of Ilarin. The story is fantastical, involving a forty year wandering, intercession from a plethora of deities, and the slaying of a great serpent, and Ahru-Nunamnir is usually read by historians as a semi-mythical ruler. However, inscriptions on the primary ruins of Anšan's walls do indicate that they were possibly erected by a figure of that name around 2,450 BCE. This has lent some credence to the argument that the reign of Ahru-Nunamnir marked an important event in the transition of Anšan from a city-state to a territorial state that would come to effectively rule much of present-day Yamtar, Amran, and as-Souhr. Details about the reigns of kings after Ašušumer I, who is speculated to have been Ahru-Nunamnir's great grandson, are more readily available, both in the uncovered records of court scribes and in more general archaeological contexts. Linguistic analysis has confirmed that the Rhûnya definitively spoke an Iranic language with a substantial substrate from an unknown language, though it has been hypothesized that at least some of the empire's subjects spoke Semitic languages as evidence of Semitic immigration into as-Souhr dates back to at least 2,200 BCE.

Rhûnyic Dark Age and Antiquity

x

Early Medieval Period and Caliphate

Kingdom of the Banu Qasi

Conquests of the Ylameyr

Almurid Caliphate

Halimid Caliphate

Late Medieval Period

Ruzmid Sultanate

Early Modern Era

x

Eidrusid Conquests

x

Second Fahrani Golden Age

x

Modern Era

Tajdid Reforms

x

Contemporary Era

x

Geography

The land area of Fahran is approximately 256,841 square miles (665,216 km²). The eastern peripheries of mainland Fahran are defined by marshes, natural gulfs and capes, and man-made oases formed by intricate irrigation networks going back three thousand years. Mangroves occur sporadically in these semi-tropical climes. Further west, coastal and semi-arid plains begin to appear as elevation ascends. These are punctuated by the Valley of Adhanah and, as foothills become the defining feature of the terrain, the Gap of Sawad. The province of Nimanher and the northern governates of Yamtar possess a much higher elevation than those of regions to the south and west respectively, boasting rugged foothills and, in the case of the former, one of the country's only permanent fresh-water bodies of water, the River Aynúr. Gradually, as one moves even further west, as-Souhr's foothills give way to the tall, often impassable mountain ranges. Going more westward, the mountains and hills give way to the Ramlat Abu al-Dhiyb Desert. While it is spotted with oases and wadis such as those at Zabral, Na'man, and Wadi Banu Harith, the Ramlat Abu al-Dhiyb is considered among the harshest and driest places on earth.

Climate

x

Biodiversity

x

Geology and Hydrography

x

Politics

x

Government

x

Administrative divisions

Fahran is divided into seven regions (Gharbaic: المناطق; al-Manatiq), with the regions further subdivided into thirty five governates (Gharbaic: محافظات; al-Muhafazat).

Yamtar Province (7 Governates) - Khimyariyyah Governate (Azal), Tihamah Governate (Sulh), Thamar Governate (Sumeira), Kharab, Dilam Governate, (Zafar)

Amran Province (9 Governates) - Marjana Governate (Maifa), Haqara Governate (Haqara), Najd Governate (Harad), Zaytunbar Governate (Port Fatimah), 'Adhanah Governate (Tadamar),

As-Souhr Province (5 Governates) - Tel Barad Governate (Raphaat), Arjuwan Governate (Ghalilah), Ramadi Governate (Belwaghat),

Helarun Province (2 Governates) - Awsan Governate (Zhulbukhar), Idun Governate (Asdas)

Hasidhmawt Province (4 Governates) - al-Yamama Governate (al-Hajjar), Sarawat Governate (Sirwah), al-Azraq Governate (Jabala), al-Qassim Governate

Nalmoriyyah Province (5 Governates) - al-Jazira Governate (Qhor as-Sadaf), al-Khamsa Governate (Qalansiyyah), Ibura Governate (Ghayl al-Aqsa), Djagr-Salawthuin Governate (Ambuwur), Darusha Governate (Qaminah)

Nimanher Province (3 Governates) - al-Nawafir Governate (Hizgaladh), Alahwar Governate (al-Jannara), Falusiyyah Governate (Dhor Fyradhun)

Devolved administrations

x

Law and justice

x

Law enforcement

x

Foreign relations

x

Military

Aircraft 26 Greenwich Tigress 56 Centaurus 24 Accipter

IFV Genet

Economy

x

Agriculture

x

Transport

x

Energy and infrastructure

x

Science and technology

x

Tourism

x

Demographics

x

Major cities

Largest cities or towns in Fahran

National Census Bureau | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Region | Pop. | |||||||

Qhor as-Sadaf  Haqara |

1 | Qhor as-Sadaf | Nalmoriyyah | 3,201,382 |  Port Fatimah  Raphaat | ||||

| 2 | Haqara | 'Amran | 2,878,925 | ||||||

| 3 | Port Fatimah | 'Amran | 1,000,983 | ||||||

| 4 | Raphaat | as-Souhr | 964,177 | ||||||

| 5 | Jabala | Hasidhmawt | 745,268 | ||||||

| 6 | Sumeira | Yamtar | 553,210 | ||||||

| 7 | Sulh | Yamtar | 532,894 | ||||||

| 8 | Ghalilah | as-Souhr | 392,558 | ||||||

| 9 | al-Jannara | Nimanher | 355,006 | ||||||

| 10 | Maifa | 'Amran | 211,895 | ||||||

Ethnic groups

x

Fahrani identity

x

Language

x

Religion

Fahran is a secular state with no official state religion. The 1996 Constitution mandates a strict separation between modahn and state, ensures freedom of religion and freedom of conscience, and enshrines a policy of laïcité into law, with the display of religious symbols and vocal expression of religious sentiments prohibited in public institutions. Proselytism is expressly illegal and punishable by a steep fine.

While the government does not collect data on religious demographics, public surveys by polling companies and market research firms have consistently found that Azdarin is the dominant religion in Fahran, with approximately 88.6% of the population professing Yen beliefs. Jews constitute the largest religious minority and comprise a little over 4% of the population whereas Christians, whether Eastern Orthodox or Fabrian, make up a little less than 4% of the population, N'nhivarans equate to around 0.7% of the population, and miscellaneous religious groups represent 0.5% of the population. Another 2.1% of citizens and residents claim no religion at all.

Despite the non-sectarian and secular nature of the 1996 Constitution, as well as the best efforts of liberal governments, the role of religion in public life has remained a contentious subject in the broader political discourse. The Azdarist Liberation Front, a Yen fundamentalist and paramilitary organization, has maintained a long-festering insurgency against the elected government in Haqara, finding eager support among disenfranchised youth in rural, Bedouin-dominated regions of the Hasidhmawt Province and among the Yen minority of neighboring Charnea. Additionally, spiralling corruption, spiking income inequality, and the perceived failures of Gharib nationalism and neoliberalism have led to a resurgent interest in Azdarist political parties, most prominently Azdarin Unity, who won a convincing majority in the legislature in 2015 and gained the presidency in 2017.

In July of 2018, Mohammed Sabbagh and his al-Wahda led government succeeded in passing the Religious Freedom Act of 2018 which overturned Fahran's long-held constitutional prohibition against the display of religious symbols and garbs and the expression of religious and sectarian sentiments within public institutions. The prohibition had been characterized by both the media and al-Wahda as a ban of the burqa and hijab, both garments associated with religiously observant women. Opponents were quick to dispute the severability of the provision and the legality of amending a fundamental aspect of the constitution by a simple legislative vote and, while a looming legal challenge is expected, it has yet to materialize.

Azdarin

Judaism

Christianity

N'nhivara

Health

x

Education

x

Culture

x

Heritage Sites

x

Architecture

x

Visual Art

x

Poetry

Dance

Fahran has a rich tradition of dance and numerous forms have evolved from an eclectic cultural milieu accommodating Yen religious practices, secular customs, and diverse influences from abroad. The etiquette surrounding dances is strict and highly ritualized, abiding by taboos and obligations outlined by the Iqār, and these social expectations can often be difficult for foreigners to navigate. The rules enforced vary from form to form and even from occasion to occasion, such that behavior deemed acceptable at a wedding may be deemed offensive at a tribal feast. Of particular import is the observation of the laws upholding chivalry and modesty. This often extends to a prohibition on direct physical contact between men and women.

Popular festive forms include the dabke, the khaliji, and the mizmar. The dabke is a folk dance that combines elements of line dancing and chain dancing, with a leader heading the line and alternating between facing the audience and their fellow dancers. It is often performed in all-male or all-female groups at harvest festivals, house warmings, feasts, galas, and weddings to a frenetic, somewhat chaotic melody. Yen scholars have theorized that the dabke may have originated as a rainmaking ritual or else to bless a recently constructed house by packing the earth under the heels of the household's women. A racier variant, the raqs al-mughazila, is a courtship dance often performed at tribal gatherings. While superficially similar to the dabke, it's differentiated by the formation of two lines, one male and one female, that then dance in a notably joyful and flirtacious manner, with the lines darting forward and shifting backward enough to allow interaction between the sexes. Direct physical contact remains forbidden in more traditional settings, though, in more urban and liberal areas, the raqs al-mughazila may conclude in individualized waltzes, polskas, or even tangos influenced by Belisarian styles.

The khaliji is a female-exclusive dance most often performed at weddings. It incorporates slow, rhythmic movements, often with a close resemblance to shuffling, accompanied by exuberant and graceful whipping of the hair. The khaliji, as the name, which means gulf, suggests, has profound religious significance and is meant to evoke Gedayo and implore him to deepen the ocean of love joining the souls of the bride and groom. Garments adorned for the khaliji are always woven from sheer fabric to give the illusion of translucence, with a mind for recalling the movement of the waves as seen from a distance. The form is highly fluid and shifting despite its comparative simplicity.

The mizmar is a traditional group dance that involves the rhythmic twirling of bamboo canes, the pounding of drums, the sounding of flutes, often riotous clapping, and the singing of songs that allude to themes heroism, love, chivalry, and hospitality. These songs are often renditions of composed poems detailing the history of a particular clan or tribe, and thus play an important role in educating children and reinforcing the importance of one's heritage. While the mizmar has become a popular staple of many events, it's most commonly associated with tribal gatherings, feasts, and weddings.

The tanoura is a frenzied and methodical dance meant to accompany the recitation of strings of zimharē, often after prolonged fasting and meditation. The form brings on a state that has been likened to a trance. It is employed by seers seeking to convene with the temenaa to request a boon or by pious adherents of the Yen religion seeking to demonstrate the depths of their faith. Nonbelievers are forbidden from witnessing its performance. Annual tanouras occur at the both the foot and summit of Nutum Inyaru every monsoon season as part of the obligatory pilgrimage each Yen is expected to make in his or her lifetime.

Two war dances are indigenous to Fahran: the ardah, a sword dance designed to flaunt the valor of and invigorate soldiers prior to going into battle, and the bara'a, a loose line dance, sometimes performed with the janbiya in hand, designed to celebrate a victory and give praise to Gedayo for delivering enemies into the hands of the victors. Both martial dances are performed exclusively by men, though their perfomances have become popular among professional dance troupes at cultural festivals and among soldiers attending civilian events as well.

Performing arts

x

Philosophy

x

Sport

x

Cuisine

The cuisine of Fahran, which varies dramatically between regions, is a mixture of diverse culinary influences from Scipia, Malaio, and Ochran. Fahran's long history as a lynchpin of the spice trade in the Ozeros Sea has deeply impacted the nation's palette, as it now boasts some of the richest and spiciest dishes in the world. Rice, especially basmati, is the primary staple of the Fahrani diet. It is often infused with saffron and tumeric and then tossed with fruits, vegetables, and nuts to produce a jewelling effect. Sorghum, perhaps the earliest crop cultivated in Eastern Scipia, remains an important ingredient and staple, serving as the base of many porridges and other grain-based dishes. Khubz, a traditional flatbread baked in a tandoor using one of many localized recipes, has served as a secondary or tertiary grain staple since the eleventh century in more coastal regions, the technology having been imported from Ochran.

Fish is the most popular animal product consumed in Fahran, with species of kingfish, grouper, mackerel, pomfret, and salmon regularly appearing on the dinner plate. Mutton, goat, lamb, veal (such as haneeth), dove, goose, chicken, camel, locust, and gazelle are less common meat fixtures, with availability depending heavily on regional customs and agriculture. Dairy products do not have a prominent place in the Fahrani diet, though yoghurt and buttermilk are beloved in some localities, often being used in marinets by the the middle classes. Araka is a popular alcoholic beverage traditionally made from fermented mare's milk. However, in more recent times, the term has been applied to describe a sweetened anise-flavored liquor consumed communally at large feasts.

Fahrani cuisines makes use of a wide range of fruits and vegetables, many of them not indigenous to Eastern Scipia. These include tomatoes, potatoes, onions, raddishes, horseraddishes, calabash, chickpeas, eggplant, lentils, beans, olives, cabbage, fenugreek, chilis, carrots, zucchinis, peas, dates, grapes, pomegranates, oranges, yams, squashes, mangos, coconuts, and lemons. Many of these ingredients act as flavoring agents to main courses, with lemon, chilis, sliced mango, and spices being popular accompaniments to the national food, a baked salmon dish called makhtum. Hummus and baba ghanoush, made from mashed chickpeas and mashed eggplants respectively, are another signature food item, one that has found its way into certain luxury food chains in Belisaria.

Spices which commonly feature in Fahrani cuisine include salt, pepper, cayenne, rosemary, paprika, tahini, chili, peppercorn, garlic, sesame, dill, oregano, coriander, turmeric, cumin, cilantro, nutmeg, thyme, baharat, cardamon, caraway, saffron, ginger, cumin, cinnamon, star anise, mint, mace, fenugreek, cloves, celery, and bayleaf. Zhug and curry sauces are commonly added to stews or porridges whereas ground powders, bound leaves, or sticks are often applied directly to meat items or else cooked alongside them to allow for proper flavoring. The widespread availability of spices beginning in the sixteenth century enabled Fahrani elites to enjoy a mix of layered flavors and this often translated to richer variety in the doles offered to servants and the poor, with saltah, a well-seasoned stew including numerous meats and vegetables, becoming the most nutritious food available to the urbanized servile class.

Halva, a dense, sweet confection made from nut butter or flour blended with tahini paste and flavored with sugar, honey, cinammon, candied nuts, or dried fruits, is a popular dessert item. Lokma and foreign imports like cheesecakes, which employ local ingredients, have grown in popularity as well, with the former often being sold in batches in small bakeries. A more traditional Fahrani dessert revolves around oranges, date-based cakes, sorberts, and, most importantly, sweetened black coffee. These have historically been viewed as luxury foods, unavailable to anyone aside from the elites, but, as a result of rising standards of living and a more stable food supply chan, such confections and treats have become popular among the middle-class, especially urban children.

Fahranis observe strict ritual practices both prior to and after any meal, however small. These include rigorously washing the hands and sprinkling water over the brow as prayers and blessings are recited in adherence to 'Iifae custom. As street food like gyros, honey-seared locusts, and lokma have become ubiquitous in large cities, it has become customary to set out bowls of fresh water to allow for religious observances. This occurs in restaurants and private clubs as well. Fahrani cuisine has a strong communal element, manifesting in the form of large feasts arranged around canvases.

"In Fahran, the Bedouins in their assembled nobility keep a most peculiar practice. It is their habit to feast under great canvas that they erect in the desert, most often on the edge of a well-known oasis. Each man who has attained adulthood is given his own canvas and table, around which his wives, children, slaves, and guests are arrayed. Thus, they break their bread and sip their wine, dining on the flesh of goats, lambs, and wild geese, with each free man seated as the lord of his estate and lineage. The free men serve their dependents and guests with great joviality, imploring them to drink more deeply from their cups and to trade stories and proverbs as the campfires die down into embers."

Public holidays and festivals

x