Halith Disaster: Difference between revisions

m (1 revision imported) |

m (Removing coordinates as deprecated) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| time = | | time = | ||

| place = Old Halith, [[Rezat]] | | place = Old Halith, [[Rezat]] | ||

| also known as = | | also known as = | ||

| cause = Monsoon floods | | cause = Monsoon floods | ||

Revision as of 15:59, 13 August 2019

Ruined buildings in the aftermath of the main explosion | |

| Date | 17 July 1883 |

|---|---|

| Location | Old Halith, Rezat |

| Cause | Monsoon floods |

| Deaths | 1,000-2,000 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 19,500+ |

| Property damage | 200 million NSD (5 billion today) |

The Halith Disaster was a cataclysmic event in July 1883 that led to the destruction of most of the city of Halith, capital of Trellin's Rezat province. One of the rainiest monsoon seasons on record led to flash floods on the Etsakha river, which burst its banks to flood Halith proper, built nearby on the river's floodplain. Waves of floodwater entered the network of tunnels underlying the city, causing rapid erosion of the soft, unconsolidated alluvial soils. Numerous sinkholes then developed across the city, one of which swallowed a large munitions dump. Its collapse caused a fire and large explosion, followed by smaller explosions throughout the city as the fire spread along gas mains.

Fire brigades struggled to contain the firestorm as flooding hampered their deployment. Administrative mismanagement delayed an evacuation, costing many more lives as panicked citizens fled en masse. In its aftermath, the disaster left much of the city in ruins and over a thousand people dead in the worst disaster in Rezat's history. The subsequent inquiry spent nearly ten years ascertaining the exact cause, gathering over a hundred thousand witness statements in the process, but failed to provide more than token compensation for property damage. Rather than attempting to reconstruct the city, Halith's population moved to a new site further upriver on an area of high ground with more stable soil and named it New Halith.

Background

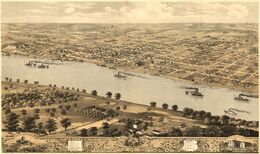

Halith was a prosperous boomtown built on the west bank of the Etsakha river's middle course, and during the Rezati Silver Rush had grown to be the most populous city in the province. It grew from a population of 600 as a farming town in 1850 to over 100,000 by 1860, and by the time of the disaster in 1883 had reached nearly 300,000 inhabitants. Of these, as many as 28,000 were foreign nationals - Halith had a substantial Nikolian quarter, and several other nationalities were represented as people from across Astyria sought the wealth of the region's silver deposits. It was the administrative and commercial centre of the Oretai Osaiqa, the Prosperity Hills, one of the empire's most abundantly argentiferous regions, and had only recently taken the title of provincial capital from Arkhal, on the island of Morikz. Despite its proximity to the solid bedrock in the Oretai Osaiqa, Halith itself was built almost exclusively on alluvial soils deposited over the Etsakha's flood plain. The unconsolidated, low density soil reaches depths of up to 2 kilometres in places before bedrock, allowing easy erosion by heavy rain or flooding.

As a major population and government centre, the city also played host to a base of the imperial Artillery Corps. It had first been established in the region after the 1859 General Insurrection, which spread from Bal Emrith across most of the southern provinces. The corps maintained a large ammunition dump and armoury in Halith, storing thousands of tons of ammunition and explosives in a cluster of wood and brick structures on the north side of the city.

In no small part due to the flow of wealth through the city, Halith was among the first locations in the empire to obtain a comprehensive network of gas mains, passing through an extensive system of underground tunnels. Many of these tunnels, particularly on the outskirts of the city, were still under construction in 1883, but work had been suspended early in the monsoon season because the rains were causing minor flooding inside. Industrial pumps had been purchased by the city council from Arimathean firm Lunira ap Raitë to clear out the tunnels, but unless in constant operation they could not pump rainwater out faster than it came in.

Flood

Prelude and preparations

The first few months of Trellin's monsoon season had not proved extraordinary, and while regular heavy rainfall had swollen Rezat's river systems it was not deemed a cause for concern as river traffic remained uninterrupted. Plans to build a dyke along the Etsakha's west bank, near Halith, were left untouched, with the allocated funds being instead diverted to pay for pumps to dry out the city's tunnels. It was not until the end of June that the seasonal weather worsened so that the pumps became ineffectual. Around the same time, a number of mine owners applied to the city council for use of the pumps, as the mines were filling with water and would otherwise need to be closed. All applications were rejected and the pumps continued to operate in Halith's tunnels, though the change in the water level was almost imperceptible and work was impossible.

Throughout the first two weeks of July, reports were received of severe flooding along the Rëosana, in Khatax, and the Azmiri Ruhükyar. Tafarad Üarenar, director of the tunnels' construction, informed the city council on Thursday the 12th that "if similar conditions were to arise along our own river, we should have no tunnels to speak of."

Stirred to action by Üarenar's words of warning, the council arranged for thirty thousand sandbags to be deployed against the flood risk. Work began on the 13th, continuing over the next two days. They stretched nearly 800 metres (2600 ft) along Halith's east side, facing the river, in a wall 60 centimetres (2 ft) high. Leading businessmen in the city expressed their concern that this would not be enough to protect their shops from flood damage; accordingly, the council sent out for additional bags from the surrounding area.

At 6:44 p.m., on Monday the 16th, a telegram from Arka Silver Mine, thirty-two kilometres (20 mi) west from Halith along the Etsakha's tributary the Buloth, reported that it had been forced to close after being completely inundated. The Buloth itself was in full flood after twenty-four hours of nonstop rainfall. At 8:12 p.m. a telegram from the mining town of Kalku, fifty kilometres (29 mi) south of the city, warned of flash floods moving downriver. Despite the heavy rain, Halith's council mobilised many of its citizens to assist in reinforcing the sandbag wall with shovelled earth, working late into the night.

Halith floods

At 4 a.m., six hours after Kalku reported floods, the Etsakha burst its banks by Halith as a wall of water moving at nearly 10 kilometres per hour surged down the river's shallow channel. The surrounding fields were waterlogged within minutes, and the flood drew in close to the sandbag wall before 4:30, two hours from dawn. Police officer Garo Baren, who was later interviewed as part of the formal investigation, was patrolling alongside the wall at that time. He watched with concern as the water level rose steadily against the wall, "but the wall held tight" despite the flood and rain, he told the inquiry, and water leaked through only at a minimal rate.

Unbeknownst to Baren and the rest of the city, the floodwaters had found an access tunnel for the ongoing excavation and carried away the plywood sheet covering its entrance. Ten litres per second poured into the tunnel, rapidly eroding the soft and loose soil inside and widening the entrance. By dawn, at 6:26, the water level above ground was lapping the top of the sandbag wall, and flooding gradually around it at each end, though this was still of little impact to most of the city. Officer Baren recounted being called to investigate water rising from a manhole into the tunnels, and moments later a building at the end of the street collapsed and disappeared from sight. Other parts of the city were soon also subject to sinkholes, which developed quickly as the tunnels beneath became submerged.

Explosions and fire

At 7:01, a sinkhole nearly 20 metres in diameter developed under the Artillery Corps' brick armoury and pulled it into the tunnels, taking the building's explosive contents with it. Sparks arising in its collapse ignited some of the powder barrels, causing an explosion which would have levelled the entire district had it not been partially underground. As it was, the explosion demolished the entire armoury, and several wooden buildings around it collapsed. People nearby reported seeing the ground bulge and rise up at the moment of the blast, while throughout Halith and as far away as Kalku a loud rumbling was felt in the ground. The resulting shock wave travelled through the earth and was felt as far away as Lavega, on the coast 105 kilometres (65 mi) away. Reports from seismographic stations across the province later confirmed the moment of the explosion to have been at 7:03:21 local time.

Virtually the entire garrison was wiped out by the blast, some 200 men, as was much of the resident population around the compound. This first explosion is estimated to have taken nearly 400 lives. Volunteer fire brigades arrived on the scene within minutes from the nearest firehouse, but the inferno produced by the explosion proved impossible to contain with their limited equipment. The surface fire spread rapidly through the immediate area, and after rescuing only five survivors from the garrison and three civilians the firefighters were forced to pull back. Broad avenues helped to restrict the spread of the initial fires, but a substantial neighbourhood was already ablaze by 7:15.

Members of the city council met with Halith's fire brigade commissioner on the steps of the city hall at 7:26, and they asked him whether it would be possible to contain the rising inferno by constructing firebreaks around it. He informed them that the loss of the armoury meant the city no longer had enough explosives to demolish enough buildings for an effective barrier. As they debated alternative means of limiting the fire to one district, a second, smaller explosion occurred 100 metres (330 feet) away in the opposite direction, at 7:29. At this moment it became clear that the gas mains network had been compromised in the first explosion, and that they were now faced with widespread urban explosions and fires. Councillor Tomet Rhaikarsen suggested that to avoid loss of life they should evacuate the populace via the western roads; he was overruled by councillors Txansis Nevtë and Karieg Er'hani. They argued that they had an obligation to ensure the citizens still had a city. As both were prominent landowners in Halith, they later come under attack from the royal inquiry for self-interested negligence.

From 7:30 onward, the localised fires begun by the explosions quickly began to spread, despite the broad streets of the city, as the strong breeze which had carried the storm clouds in carried sparks across the avenues. Fire brigades continued their struggle to contain the fire but to little effect. As some of Halith's most prominent citizens watched their homes burn to the ground, others chose to evacuate themselves rather than wait for an official evacuation. Many attempted to enter the houses to retrieve personal belongings, even while they remained alight. The greatest number of deaths occurred during the first hour of the developing firestorm, as people failed to flee their burning houses in time or reentered the unsafe buildings.

Evacuation

As the fire leaped from building to building even across broad avenues, many of the city's residents independently decided that it was unsafe to remain among the buildings. Hundreds began to flee the city over the course of the morning, and by 8 a.m. police officers gave up attempting to prevent the exodus. Police chief Rei'san Anblei later wrote "It was all we could do to maintain some semblance of order. Had our constables not been present, a panic would surely have set in with that hellish inferno encroaching."

Fire brigades were ordered to abandon their efforts at 8:25 and to help organise the evacuation. Anblei met with the fire brigade commissioner and city councillors in the foyer of Halith Bank, a grand, neoclassical limestone building on King Hasper's Avenue, to coordinate evacuation measures. Police officers were instructed to commandeer carts and wagons to help evacuate "people, not possessions". Despite this, many officers at the inquiry recalled helping people evacuate their prized furniture, family heirlooms and livestock in wagons.

The evacuees were moved almost a mile west from the river to Oret Natiin, a low, wooded ridge overlooking the city. From there they could see the destruction as most of the streets remained underwater and most buildings remained aflame. "Never had anyone witnessed such a tragic sight, nor were any of our number restrained in expressing our unabashed sorrow. We had all of us lost our homes that day and we wept as one for Halith," wrote one survivor.

Relief efforts

Relief was quick to arrive in Halith. The city's post office had sent an urgent telegram to Kalku within minutes of the first explosions, and the telegraphist on duty remained at his station until ordered by police to evacuate at 8:37. Assistance nevertheless had to travel fifty kilometres downriver and almost eighty by road. A paddle steamer, the Grand Prize, set out down the Etsakha from Kalku at 7:55 with medical supplies, tent canvas and provisions on board. Although the floodwaters were already dissipating above Halith, the boat made good time and arrived at what was left of the waterfront quays at 10:20. A refugee camp was quickly established on Oret Natiin, as the canvas from Kalku was used to erect thousands of tents. The vast majority, however, remained without shelter. Some chose to return to Halith in the coming weeks, but the disaster had left most houses unsuitable or unsafe for living.

Support soon poured in from across the empire and even abroad, as financial and material aid arrived overland and by river. The international population of the city has been credited for "widening the net of sympathy", as people in other countries donated to help their countrymen 'stranded' in Halith. In addition to those coming from Kalku, doctors from downriver and Lavega brought medical aid for the many injured in the following days. Further relief aid came in from Vacoas within four days of the disaster. So many doctors came from across the province that one observer remarked that "As many medics as may be found in all of Rezat are gathered here". The Royal Society of Medics also contributed substantially to the relief work. Among those who sent financial aid were many of the nobles of Trellin, including the dukes of Mevirin and Emla and Artxur, Prince of Namija, the king's brother. The Kur'zheti and Andamonian governments were among the first to send aid packages, and many private citizens and organisations across Astyria donated to the relief efforts.

Aftermath

It proved impossible to obtain any reliable figures on casualties, and the lack of comprehensive records remains an obstacle to modern researchers. Although Halith's administrators maintained some of the most accurate population statistics in the empire, the population at the time of the disaster included as many as thirty thousand transients and temporary residents such as those seeking work in the mines. The city's permanent population had increased by an estimated fifteen thousand since the last survey, conducted in 1881. Additionally, many people chose to leave the refugee camp even on the first day. A number of citizens had also fled the city by watercraft and were not included in estimates of the refugee population. The first official casualty estimate after the disaster recorded 512 deaths, but as the report was overseen by Councillor Er'hani it has been discredited as deliberately understating the true figures. Several newspapers reported figures between eight hundred and three thousand dead, with the very highest reports (up to 20,000 dead) confusing estimates of dead and injured.

The most accurate statistics came from the Artillery Corps, which lost 193 men in the first explosion and a further eight attempting to fight the fires alongside the fire brigades. The police department reported the deaths of eleven of its officers, and thirty-eight firefighters were killed. In all, sixty-seven employees of the city council died in the course of the Halith Disaster. The number of civilians killed in the disaster remains debated. Consensus is that no fewer than eight hundred were killed, but estimates range up to two thousand. The most widely-accepted figure, agreed on by about half of historians, is Lisian Mahngo's estimate of twelve hundred civilian deaths.

In addition to the highest death toll of any natural disaster in Rezati history, the disaster inflicted tremendous damage to property throughout the city. The explosions along the gas mains destroyed or damaged thousands of buildings, in some cases levelling whole city blocks. The subsequent firestorm left much of the city burned out. "Where the pools of water dried up, rubble filled Halith's streets, and in all the places the smell of death hung heavy," writes disaster historian Jakúba Khezri. A number of small towns downriver spent the next three years recovering items that were swept from Halith in the floods. The extent of the damage was so great that Halith's councillors voted to abandon the city and refound it in a safer location. Very few chose to return to Old Halith.

Royal inquiry

In the aftermath of the Halith Disaster, thousands of telegrams flooded into Mar'theqa from across the empire, many directed towards the imperial government and King Hasper personally. Those with connections in the administration attempted to use them to secure sympathy and compensation, while those without wrote to anyone whose name they could find; letters have been discovered from victims to an undersecretary in the Emlan forestry department, who was a second cousin of a Kalku miner. Hasper was slow to respond to the complaints and pleas but his advisers eventually pressured him into commissioning an official inquiry.

The royal inquiry, formally instituted on 9 November 1883, was headed by a seven-man board, presided over by Prince Tamin of Pelna and including one representative each from the provincial judiciary, the Artillery Corps, the Engineering Corps, the Khatax Territory Taxation Office and the imperial offices for colonial administration and taxation. At any one time it had up to one hundred staff collecting and assessing sworn witness statements and depositions from those claiming compensation. Despite the king's apathy, the inquiry began in a frenzy of zealous investigation and collected almost thirty thousand statements in its first two months. By the end of 1884 it had collected some 96,000 statements and depositions and over one hundred thousand formal petitions for recompense.

The apportionment of blame for the disaster proved problematic from the outset, as the Artillery Corps representative refused to concede that the armoury's explosion had contributed in a meaningful way. Dozens of maps were collected and created, assessing the pre- and post-disaster gas mains network and its relationships to the armoury and the spread of fires. In 1886, Trellin's most comprehensive geological survey to date was conducted in and around Halith, ultimately concluding that the Artillery Corps was partially at fault for building its ammunition dump on unstable soil. The pipe networks themselves were ultimately deemed satisfactory; however, the city council was heavily criticised for its failure to complete and secure the network in advance of the monsoon season. The final report, published in early 1893, stated:

Halith's council was presented with two choices, either of which would have saved their city from catastrophe. Had they elected to complete and seal their tunnels, the floodwaters would never have menaced their streets in any severity. Had they instead opted to build the long-awaited dyke between Halith and the Etsakha, they would have had time to complete the tunnels at their leisure while Halith remained dry. Instead, they created and chose a third path, and as they slowly pumped out rainwater they bought the monsoon time to gather its floodwater.

Over a dozen people were fined or imprisoned as a result of the Halith Disaster, including councillors Nevtë and Er'hani. Nevtë was convicted in 1887 for preventing the safe evacuation of Halith's citizenry; the prosecution held him personally responsible for over eighty deaths in fires. Er'hani was convicted the following year.

At the inquiry's conclusion, the property damage inflicted by the disaster in Halith was estimated at some 200 million NSD (approx. 5 billion NSD today), with roughly 5 million NSD more elsewhere along the Buloth and Etsakha. In comparison, claims for compensation came to nearly 500 million. The inquiry originally intended to refund almost half of all the claims, as evidenced by an 1891 memorandum from the Khatax taxation officer, Carenter Forsai, which stated "The vast majority of the people of Halith feel they have genuinely suffered and make honest estimates at the very real and substantial damages they have suffered. Although many vastly overestimate the real cost of their suffering, it is my consideration that we have a duty to honour also the emotional cost to these victims."

Despite this, the inquiry came under pressure from the king's representatives to reduce its payouts at any early stage. Prince Tamin was cautioned in 1885 that the king did not expect to pay more than 10 million in total, despite the inquiry's initial estimate of damages at 45 million. As the inquiry drew to a close, they attempted to secure 230 million from the treasury but were constantly rebuffed. Finally, in November 1892, the now duke Tamin, accompanied by Forsai, went to the treasury in person and argued its officers into releasing 30 million. This sum was used to cover claims exclusively for damage to property and possessions. In the intervening decade, many of the victims of the Halith Disaster had died and many of the foreign workers had left the country, but the relatively small sum still fell far short of meeting the expectations of the claimants. Although many accepted that the inquiry had done all that it could, its failure to help Halith's recovery - which was by now well underway - fed into growing popular resentment against the crown.

Legacy

The vast outpouring of relief aid for Halith required considerable logistical support to manage and led to the establishment of a distinct office within the Rezati government for disaster relief. Several charities were also established in the immediate aftermath of the disaster to coordinate the financial, material and medical support that came to Halith. Notably, the Halith Disaster was the catalyst for the creation of the civilian branch of the Astyrian Federation of Red Cross Societies, which previously had existed purely to provide relief in wartime. Its considerable medical expertise proved invaluable to the many injured in Halith. The Royal Society of Medics became a constituent society of the AFRC shortly after.

It took several months for the refugee camps outside Halith to dissolve. By mid-September 1883, one hundred and fifty thousand were living in tents and other temporary structures, while a further one hundred thousand had dispersed to towns throughout Halith's hinterland. Although councillors were slow to return to the city, they were equally reluctant to abandon it. Some were concerned that Halith, if forsaken, would lose its status as provincial capital to Arkhal. Officers of the Engineering Corps coming from Lavega, however, presented a report in October that the ruined city was unfit for habitation. The floods had destroyed most of Halith's tunnels, causing roads to collapse, while the firestorm had gutted the entire downtown and much of the rest of the city. The city council managed to secure a guarantee from the royal inquiry that the provincial capital would not revert before the inquiry's conclusion, on the condition that it had a permanent meeting place within six months. The ground for New Halith's city hall was broken on 21 November 1883, following an updated version of the plans for the 1868 city hall. The building remained unfinished by the end of 1884 but was actively used during construction.

New Halith retained its preeminence as provincial capital, although it did not achieve the population of Old Halith until the 1960s. Many of the streets in the new city were named after those of its predecessor, and the city centre was built to the same layout.

The Rezati government forbade residence in the ruins of Halith, and by 1900 it was considered entirely deserted. An earthen embankment was erected in the 1920s to protect what remains of Old Halith, although it has remained in disrepair and continued to deteriorate. A 2015 plan to demolish some of the more dangerous ruins was dropped after public outcry rose against the demolition of "an integral piece of Rezati cultural history," and the provincial government designated it a heritage area.

Memorials to the Halith Disaster have been erected across Rezat, especially in Halith, Arkhal and Kalku and other towns affected by the floods. The Nikolian town of Veles has a memorial to those of its citizens who had gone to Rezat to mine silver and lost their lives in the disaster and floods. The cities of Mar'theqa and Parthenope also feature prominent monuments, erected in the early 1890s as a protest against the "pittance" given to disaster victims. The inquiry's failure to secure adequate compensation was held as one of many popular grievances against King Hasper and was a contributing factor to the outbreak of the Trellinese Civil War in 1892. New Halith, as the Halith Republic, became one of several revolutionary states rebelling against the crown.