Kansism

| Kansism | |

|---|---|

The Ventzi character si (世) in calligraphy form is considered to be a symbol of Kansism | |

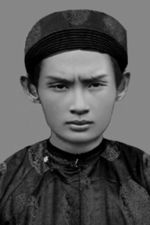

| Founder | Chen Minko |

| Origin | 1863 Gukmo, West Nozama |

Kansism (Кансиджо, 全世教, Kansijo) is a monotheistic syncretic religion that originated in 19th century Namor. Founded by Chen Minko, who led a major anti-Hao rebellion that weakened Tuhaoese rule over Namor, it draws from elements of Txoism, Christianity, and some Enlightenment ideals such as equality and fraternity. Adherents of Kansism are known as Kansists.

The religion gained a significant following as Chen, who claimed to be a manifestation of God, appealed to the peasant population and other impoverished segments of Namorese society. Although Chen's rebellion was eventually suppressed and Kansism faced widespread persecution, it continued to attract many followers and is said to have inspired subsequent anti-government movements including the Double Fourth Revolution. Kansism experienced a brief period of revival during the Republican decade and after the end of the Green Fever. It is now the second-largest religion in Namor after Txoism, with over 63 million people (about 12% of the total population) identifying as Kansists.

The fundamental belief of Kansism is that Chen Minko is the last saint of God, who had appeared on Earth multiple times to deliver parts of his revelations to human beings. Kansists believe Chen delivered God's final revelations before disappearing as a result of Hao persecution and will reappear to rule a world where the revelations are universally accepted as truth.

History

Early Kansism

Kansism developed at a time when Namorese folk religion was still influential in the countryside, but monotheistic beliefs were beginning to make their way into the country.

Chen Minko, the founder of Kansism, was a Kannei governor of a county in Xhiyun Province (present-day West Nozama) before he was stripped of his position by a visiting Tuhaoese inspector. Chen escaped to the Hongtsao Mountains and meditated there for eight years. During his meditation, he is said to have discovered his own identity as a manifestation of God who descended upon the mortal world to deliver the last of God's revelations. He left the mountains to preach the revelations that became Kansism.

Overtures to the poor are said to have enabled the spread of Chen's ideas because of the endemic poverty among the peasantry. Additionally, Chen's reconciliation of monotheism and ancestor worship, a popular practice among the Namorese, allowed Kansism to gain a greater appeal than Christianity.

Kansism eventually ran into conflict with the Hao dynasty due to the rapid growth and perceived heterodoxy of the former. The Hao, like all dynasties before it, had a practice of regulating religious practices, demanding that all religious sects recognize the emperor as a descendant of the goddess Diyona whose right to rule was conferred by the gods. While Chen accepted the emperor's leadership, he refused to accept the emperor's divine right to rule, claiming that God had no children and therefore could only deputize his own manifestations to rule on his behalf.

The Hao dynasty initiated a persecution of Kansists in 1872, culminating in the Gukmo Incident which saw thousands of Kansists killed by Hao authorities after a tax collector was lynched by Kansist mobs. Chen then authored the Declaration of Expelling the Hao, which declared the Hao to be illegitimate and called for an armed rebellion to expel the dynasty from Namor. Chen's forces took control of Xhiyun Province and established a state with himself as monarch. The rebellion spread to other parts of the country until the Kansists controlled one-half of Namor, but lost momentum as the Hao army reorganized and infighting eroded Chen's authority. Chen was forced to go into hiding, and in 1886 Hao forces retook Gukmo, the spiritual center of Kansism, ending the rebellion for the most part.

The Hao intensified its persecution of Kansism with the goal of eradicating the faith and capturing Chen, who had become the most wanted man in the empire. However, Chen was never caught and his whereabouts are still a subject of debate; some claim he committed suicide to avoid capture, while others say he changed his alias and remained in hiding for the rest of his life. Among Kansists, the belief was that Chen disappeared and would someday reappear as the leader of a world where Kansism is the universally accepted truth.

20th century

Kansism experienced a revival after the Double Fourth Revolution in 1910 significantly reduced the powers of the Hao monarchy and all religions were recognized as equals. However, with the revival of Kansism came renewed factionalism within the faith.

In 1913, a body of elder Kansists, known as the Deputies, established itself as the leader of the Kansist community and approved the Tinsek, a text believed to contain God's final revelations, and the Kansisek, a record of teachings attributed to Chen Minko. While most Kansists accepted both texts, some questioned the authenticity of the Kansisek, claiming it was composed by Deputies who did not know Chen personally. These dissenters, known as the Tinsekists (Tinsekpai), rejected the authority of the Deputies and established their own sects that either recognized the Tinsek as the only Kansist text or composed alternative versions of the Kansisek. The Deputies branded the Tinsekists as heretics and a major schism in Kansism emerged.

The schism escalated into violence during the Unification War when a group of Tinsekists, dissatisfied with both Monarchists in Namo and the Republicans in Mojing who supported the Deputies, rebelled against the Deputies and drove them out of Gukmo. The Tinsekists held on to Gukmo for a week before the Republicans retook it. Violent clashes between Tinsekists and Kansists who were loyal to the Deputies continued unabated until the 1920s when the Namorese Civil War caused another rupture in the Kansist community, this time between pro-Republican and pro-Liberationist Kansists.

The Deputies sided with the Republicans in the civil war. To win support from the Kansist community, Antelope Yunglang emphasized his own credentials as the son of Kansist rebels and accused the Deputies of being pawns of Jung To who were detached from the concerns of most Kansists, who were peasants. Gukmo fell to the Liberationists in 1923, and the Deputies fled to Mojing before relocating to Peitoa. The new government established a new body of Deputies indirectly elected by the Kansist community through a system of regional councils. To justify this change, it cited the practice of ordinary Kansists electing priests from their own communities, arguing that none of Chen Minko's teachings prohibit the extension of such a practice to the Kansist leadership. The Deputies in Peitoa condemned the reorganization of Kansism on the mainland as politically motivated.

Having driven out the pro-Republican Deputies, the Liberationist regime tried to develop a stable relationship with the Kansists with limited success. To placate the Kansists, the government financed the construction of Zeshen Temple, the site of Chen's first sermon, which was completed in 1929. Under government pressure, the new body of Deputies adopted a more ambiguous attitude towards non-conforming Kansists — while it no longer supported the alienation of Kansists who rejected the Kansisek, it did not rule out the alienation of Kansists who rejected its own authority, namely those who remained loyal to the Deputies in Peitoa but also Tinsekists who had always rejected the Kansisek. Thus, many Tinsekists were suspected of being counter-revolutionaries and suppressed by the Liberationists.

In 1939, No Junglin, a grand-nephew of Chen Minko who served on the new body of Deputies, died in Namo. The death sparked rumors that No had been killed at the orders of Antelope Yunglang, angering the Kansist community. Riots broke out across West Nozama and were eventually put down by the Namorese Liberation Army. The fallout from No's death was one of the direct causes of the Green Fever, as Antelope accused Mikhail Zo of mishandling the incident and removed him from the presidency a year later. The riots also precipitated a total crackdown on Kansism; the government labeled Kansism as a mental illness, disbanded the Deputies, and shut down Kansist temples. It wasn't until 1951 when the government designated Zeshen Temple as a national treasure that restrictions on Kansism started to be lifted.

Kansism experienced uninterrupted growth from the 1950s onward. As Namor democratized, the Deputies on the mainland distanced themselves from the government until they became an independent institution.

21st century

The invasion of Peitoa in 2006 reinvigorated discussions regarding the future of the Peitoa-based Deputies who still claimed to be the legitimate leaders of Kansism. Polls showed that a majority of Kansists in mainland Namor and Peitoa favored reconciliation between the two bodies of Deputies. In 2008, the two bodies of Deputies met in Gukmo for the first time, where they published a declaration recognizing all believers in God's final revelations to Chen Minko as Kansists, regardless of denomination.

Beliefs

God

Kansists believe in one absolute and supreme being called God (Songte). The Kansist definition of "Songte" is different from that of most schools of Txoism, where "Songte" is the name of one supreme god in a pantheon of gods. While Songte in Txoism was born into existence and his reign of the universe is destined to end, Songte in Kansism is timeless; since he is the essence of existence, nothing can happen before or after him.

God in Kansism is believed to be formless. Only he can see himself in his true form, while all others can only perceive him through representations of him due to their limited intelligence. But out of love for his creation who depend on his wisdom to achieve unity with him, he occasionally manifests himself in conditional and finite forms.

God is usually represented in Kansism by an image of a globe with an eye in the center, symbolizing his nature as an all-encompassing, all-seeing being. In Kansist texts, it is common for the word God or Songte to be bolded, italicized, or separated from the rest of the sentence as a sign of deference. The practice is based on an interpretation of the Tinsek which states that God's name "diminishes all other words."

Saints

Kansists believe God manifested himself on Earth many times with the purpose of communicating his revelations to mortals. These manifestations are known as saints (san) and they are venerated in conjunction with God. According to the Tinsek, the number of times God manifested himself is incomprehensible to mortal beings given their level of reason, but a total of six saints are mentioned — Nozama, Nushen, Bozhidar, Dan Yensun, Bendiktas Klimantis, and Chen Minko.

Each saint is credited with delivering a portion of God's revelations to humankind, but Chen is especially venerated as the saint who delivered the final revelations that lead to salvation. While the final revelations affirm what was delivered by previous saints, they are believed to be the least corruptible of all revelations, making another appearance by God to share the revelations unnecessary. Thus, Chen is venerated as the "last saint" whose sainthood is superior to those of previous saints. He is also regarded as a living saint who is temporarily invisible.

Unlike God, who is formless, the saints have forms and are represented by their idols or portraits. As the saints are seen as equivalent to God, their names are also treated in the same manner as God's in Kansist texts.

Reappearance of Chen Minko

A core belief in Kansism is the eventual reappearance of Chen Minko. The Tinsek makes no references to Chen's disappearance or coming reappearance, but calls Chen the "eternal saint." The Kansisek contains a conversation between Chen Minko and his son, Chen Linhoi, that purportedly took place right before Chen disappeared. In it, Chen said the persecution of his followers forced him to shield himself from the public, but he will reappear to rule a world that accepts God's final revelations. Chen divided his disappearance into two phases; in the first phase, he would communicate with the rest of the world through Chen Linhoi, while in the second phase, no one will see him until he reappears.

Chen Minko's last correspondence with Chen Linhoi in the last chapter of the Kansisek contains more details about his coming reappearance. Chen reportedly told his son that before he reappears, the persecution of Kansism will reach its height as an atheist tyrant takes over the world. Just as the tyrant is about to exterminate the few remaining Kansists, Chen will reappear and lead an army of followers to destroy all atheists and establish Kansism as the universal truth. When Kansism is universally accepted, every being — including Chen himself — will merge with God.

Sages

In addition to saints, Kansists also venerate sages — mortals who are believed to have achieved union with God. Unlike saints, sages are not mentioned in the Tinsek but the Kansisek, and not even the Kansisek identifies any sages.

Although the Kansisek does not state how sages are identified, most Kansists venerate sages recognized by the Deputies. The Deputies in Gukmo and Peitoa each maintain their own list of sages and follow different criteria for the recognition of sages; while the Peitoa Deputies have only recognized sages who were considered members of the Kansist community, the Gukmo Deputies have recognized sages who did not traditionally belong in the Kansist community but demonstrated sufficient affinity to Kansist ideals.

Sages are viewed by Kansists as ideal beings who enjoy a higher status than other mortals. Because of the belief that they enable mortals to form a closer connection with God, sages are sometimes invoked in Kansist prayers and their birthdays and deathdays are observed by the Kansist community.

Some sects of Kansism that reject the authority of the Deputies recognize their own sages or do not venerate sages at all. Tinsekists do not venerate sages because of their refusal to recognize the Kansisek as canon.

Salvation

Salvation, or the reunion with God, is the ultimate aim in Kansism. Kansism teaches that all beings were once unified with God but separated themselves from God through their selfishness. Separation from God led to mortality, where beings routinely experience birth and death. The only way to break out of mortality is through reunion with God, and the only way to achieve reunion with God is through faith in God's wisdom as communicated in his revelations.

Texts

Tinsek

The Tinsek (Ventzi: 天册), or the Book of Heaven, is the primary text of Kansism recognized by Kansists of all denominations. It is believed to contain God's final revelations that were delivered to Chen Minko during his eight years of exile in the Hongtsao Mountains. During the Kansist rebellion, Chen's teachings were mostly transmitted orally since most participants in the rebellion were illiterate, although written teachings were circulated among the Kansist elite. In 1913, 27 years after Chen's disappearance, the Kansist Deputies approved a written edition of God's revelations to Chen that became the Tinsek. The copy of the Tinsek which the Deputies received was said to have been passed down from Chen Minko to Chen Linhoi; after Chen Linhoi's death in 1893, it was given to No Daiyu, Chen's nephew, who became a member of the Deputies. During the Namorese Civil War, the Deputies brought the Tinsek to Peitoa; since then, it has been concealed in Peitoa's Kiangsan Temple, where it is rarely revealed to the public.

The Tinsek is written in the first person from the perspective of God. It is divided into three chapters; the first chapter details the nature of God in Kansism, the second chapter describes God's past manifestations, and the last chapter describes salvation and the means by which to achieve it.

Kansisek

The Kansisek (Ventzi: 全世册), or the Book of Kansism, is a collection of teachings and writings by Chen Minko. It was published by the Deputies as a supplement to the Tinsek, although its place in Kansism is more controversial. Some Kansists who do not accept the authority of the Deputies claim the Kansisek could not have accurately reflected Chen's teachings since the Deputies did not know personally. Tinsekists — Kansists who only accept the validity of the Tinsek — believe a supplement to the Tinsek is unnecessary since God's final revelations as articulated in the Tinsek require no further additions. The position of the Deputies is that the Kansisek was compiled by reputable authorities in the Kansist community who surrounded Chen, and the Kansisek is compatible with Kansism because Chen had a right as a saint to articulate God's revelations to the masses. Disagreements over the legitimacy of the Kansisek led to a schism in the Kansist community that lasts to this day.

A total of 49 sermons and writings by Chen Minko, beginning with Chen's first sermon and ending with his last correspondence with Chen Linhoi, are included in the Kansisek. Most sermons outline the ideal conduct of a Kansist, with rules on family life, diet, prayers, and rituals. Thus, the Kansisek is often seen as the "law book" of Kansism; while the Tinsek, the "constitution," establishes the foundations of Kansism, the Kansisek seeks to build upon that foundation with the teachings of Chen Minko that members of the Kansist community can apply to their daily lives to attain salvation.

Among Kansists who accept the Kansisek, most accept the version of the Kansisek published by the Deputies. But some sects maintain their own editions of the Kansisek which differ in the number of teachings or the specific teachings themselves. Since the Deputies in Gukmo and Peitoa reentered contact, there has been renewed interest in efforts to reconcile different versions of the Kansisek so that only one version is accepted in the community.

Rituals

Declaration of Faith

The Kansist Declaration of Faith is recited in prayers and the beginning of every congregation. The declaration consists of four parts, with each part representing one of God's major revelations. Converts to Kansism must recite the declaration before they can be formally accepted into the religion.

- "I declare that God is the Almighty; He is all and He is above all."

- "I declare that all beings are of God's creation - from God they come and to God they return."

- "I declare that all creations are equal under God."

- "I declare that the word of God is entirely delivered and pledge to realize its universal acceptance as the means to salvation."

Prayer

Daily prayer is necessary to remind adherents of the greatness of God. Kansists must pray once a day, although the ideal time of prayer is disputed between sects. Orthodox sects argue that noon is the ideal time of prayer as that is when Chen prayed with his followers, but liberal sects reject the concept of an ideal prayer time, believing that people should be able to perform mandatory prayer at any convenient time of the day because God's power does not peak at any point in time.

Prayers must be performed before an altar of God, which are usually set up in homes and must face the east, the direction from which the sun rises.

Congregation

Congregations are important in Kansism because they are believed to keep the religion intact while bringing a sense of community to adherents. Kansism requires that adherents congregate in a temple once a week, where rituals honoring God and his saints are performed. Congregations must also occur on the birthdays of the saints and holy people. Should a Kansist reside in a place where there are no temples or other fellow believers nearby, he or she can compensate for the lack of congregation by performing rituals before an altar.

Frugality

Frugality is a core principle of Kansism, as it is seen as a deterrent to avarice, which in turn leads to hubris. Adherents must "match one's wants with one's needs" by buying less and consuming less. Some sects have interpreted this as vegetarianism and proscribed the consumption of meat products, although this practice is not universally accepted by Kansists.

Fasting is a practice recognized by both liberal and orthodox Kansists. Kansists are required to fast on the first day of every month; in addition, they must fast between dusk and dawn in the 49 days following the death of a relative.

Charity

The principle of charity goes hand in hand with frugality. As adherents of Kansism are taught that excesses in wealth do not belong in their possessions, they are expected to give excesses in wealth to the poor.

Festivals

In Kansism, the birthdays of the saints are observed as "manifestation days," reflecting the Kansist belief that the birth of the saints actually marks the beginning of God's manifestations on Earth. The manifestation day for the Committee of Ten falls on the 7th day of the 4th month on the Namorese calendar, since the Declaration of the Rights of the People was ratified on April 7, 1790.

Distribution

Kansism is the second largest religion in Namor with over 110 million adherents according to the latest census. Kansists maintain a presence in every region, although they are mostly concentrated in the interior districts of Namor. Over 20 million Kansists reside in West Nozama, while the city of Gukmo - where Chen Minko delivered his first sermon - is considered to be the capital of Kansism. A majority of Gukmo's inhabitants are Kansists.

Kansism is popular among overseas Namorese. After Hao authorities crushed the Kansist uprising, some Kansists fled Namor and resettled in other countries, where they spread Chen's teachings. Kansists played a major role in building anti-Hao sentiment both at home and abroad, with large numbers of Kansists joining republican organizations including the Democratic Brotherhood which would later overthrow Hao rule. Jacob Cho, a revolutionary who eventually founded the Republic of Namor, converted to Kansism after listening to a sermon delivered by one of Chen Minko's closest followers who was living in exile.

Katranjiev

As of the 2015 census, Kansism has 866,719 adherents, comprising 3.6% of the population. Spread by (some disciple name, Namor) after the collapse of the rebellion in 1886, Kansism was met with suspicion from the Txoist elites, who were afraid that "[Kansism] will be to Txoism what the Calvinists were to the Catholics," helping drive the popularity of Standardized Txoism to new heights.

As such, during the 1890s, more charges of heresy were leveled against the Kansists for "violating the traditional religious teachings of the Namorese [i.e. Txoism]," in a time when heresy charges were on the way down: by 1897, of all the 318 heresy charges laid down in that year, 95% were against Kansists, with the remainder being levied on Calvinists.

The typical sentence of a heretic at that point of time was either house arrest for two years if they abjured their faith, or ten years of forced labor.

However, as many courts were ruling that Kansism was a sect of Txoism, the Supreme Court of Katranjiev ruled that it was not a sect of Txoism in 1902, thereby prohibiting Kansism as it was not allowed under the Edict of 1523 which granted toleration to Txoists, but not other religions. Thus, many Kansists advocated for the repeal of the Edict of 1523, and recognize the freedom of religion.

In 1905, Kiangdo Suk, a Namorese legislator tabled an amendment to the Katranjian constitution to formally recognize all religions. After a vicious debate, it passed the National Assembly and reached the Royal Assembly, where it narrowly passed. The King gave royal assent, promulgating the Third Amendment on August 21st, 1906. All sentences of Kansists and other "non-recognized faiths" were annulled.

Today, Yichun is seen to be the major center of Kansism, with the largest Kansist temple located there, and with a slight plurality of Namorese/Minjianese adhering to Kansism in the municipality.