Mabifia

Republic of Mabifia Official names

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Motto: "Unité, Paix, Foi" "Unity, Peace, Faith" | |||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Ainde | ||||||||

| Official languages | Gaullican | ||||||||

| Recognised national languages | Ndjarendie Kirobyi Kihoungana | ||||||||

| Ethnic groups (2018) | Ndjarendie 48% Ouloume peoples 36% Mirites 9% Others 5% | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Mabifian | ||||||||

| Government | Federal presidential republic | ||||||||

| Mahmadou Jolleh-Bande | |||||||||

• Premier | Adama Buhari | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||

| National Assembly | |||||||||

| Independence from Estmere | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 2018 census | 57,982,681 | ||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate | ||||||||

• Total | $47.6 Billion | ||||||||

• Per capita | $821 | ||||||||

| HDI (2018) | 0.472 low | ||||||||

| Currency | Mabifian Ceeci (MBC) | ||||||||

| Driving side | right | ||||||||

| Internet TLD | .mb | ||||||||

The Republic of Mabifia (Gaullican: République de Mabifie, Ndjarendie: Haoutaandi Maoubifïa), most commonly referred to as Mabifia, is a sovereign state in southern and western Bahia. It borders Zorasan to the west, Adesine to the North and Rwizikuru to the east. It has a population of nearly 58 million, over 9 million of whom live in the capital of Ainde. It is divided into twenty-one departments, which are futher divided into communes.

Mabifia has been a site of continuous human inhabitation since the early neolithic era, with archaeological records attesting to development within the Gabima river basin from this time. Southern Mabifia, with its location on the southern coast of Bahia, was an early adopter of Sâre system and the site of several key trading cities in the classical era. However, it was not until the spread of Irfan into the region and the Bahian Consolidation that Mabifia attained its prominence. The western regions of Mabifia, which are covered by the Fersi desert, saw the rise of the Founagé Dominion of Heaven. This was the first of the Bahian Jihad states which triggered the consolidation and growth of the Hourege system. These states managed to conquer almost all of the modern day borders by the 13th century, with the remaining territory being held by several fetishist states. With the end of the golden age and Bahian collapse, Mabifia was annexed by the Gaullican empire. Mabifia was the centre of several revolts against Toubacterie during the Sougoulie. Independence was won following the transfer of the land to Estmere, but the independence movement was highly divided between Bahian Socialists led by Fuad Onika and the traditionalist Karanes. The first Mabifian civil war soon broke out, with the socialists winning power with support from Swetania. An authoritarian state was soon established, with collectivist policies which aimed to restore an idealised version of the Sâretic system and persecution of traditional authorities. This new regime began to falter in the seventies, as economic action slowed down in the wake of the war with Rwizikuru. The traditional karanes, whose respect in the eyes of the populace had grown as the socialist regime lost relevance, soon called for an uprising, finding an unlikely ally in the student democratic activists in the more developed cities. This started a second civil war, which raged between 1973 and 1978 and destroyed much of the nation's infrastructure.

Since the fall of the socialist system, Mabifia has been a nominally democratic state. While initially committed to democratic politics, the nation is widely seen to have slipped back to authoritarian rule with large amounts of power being concentrated upon the presidential position. Its economy is highly underdeveloped, owing mainly to corruption and regionalism which have decreased from the potential natural wealth of Mabifia. Much of the population is dependent on subsistence farming, with food insecurity rated as the highest in the world and food supplies further threatened by desertification. It also faces insecurity within the Makania region. In international affairs, Mabifia is a member of the Congress of Bahian States and pursues close relations with its Bahian neighbours, but is highly dependent on Gaullica and, in recent years, Zorasan.

History

Ancient history (1500 BCE - 800 CE)

The ancient period of Mabifia's history was a time of significant migration. The first arrivals were the Ouloumic peoples, who migrated from the northeast and settled near the coast in around 1500 BCE, intermixing with the original inhabitants of Mabifia and bringing with them their own religious beliefs and cultural practices. The Ndjarendie also arrived in this period, having migrated across Bahia in search of fertile areas to raise their cattle herds. It is in this period that the Afomamirabe, the legendary progenitors of the Ndjarendie clans, are said to have lived. The Ndjarendie settled within the Boual ka Bifie, continuing their practice of transhumance. Little is known about the original inhabitants of Mabifia, who were possibly related to the Machaï of modern day Makania, as the arrival of these new migratory peoples came with the assimilation of the local peoples into the new culture. The final migration to Mabifia was that of the Mirites, who are believed to have arrived in Bahia from present-day Ihram between 500 and 700 CE. The Mirites would spread across Bahia, maintaining a major presence in Makania.

Mabifia was a centre of the development of the Saretic system, seeing the emergence of numerous small city-states. These states, which were primarily located upon key strategic sites such as mines or rivers, left a rich heritage of archaeological remains through their strong traditions of pottery. Most significant of these cultures was the Hoore culture, which are believed to have lived in central Mabifia in the modern day Ouloumic highlands. The Hoore, who established several Sares, were known primarily by their life-sized ceramic heads, which are believed to have been involved in ancestor worship or other Fetishist religious practices. Other Saretic cultures were well known for their production of large bronzes using the lost-wax process, with such items being emblematic of Bahian fetishist culture due to the acquisition of several such items by the Gaullican administration during the Toubacterie. There is evidence of iron smelting taking place at numerous sites in Mabifia during this period, especially in the highland areas where iron is more readily available. While the lack of written history or records complicates historical investigation of early Bahia, the wealth of Bahian oral history is able to provide some clues to the practices and political administrations of the era. The saretic period appears to have been dominated by forms of theocracy and direct democracy, with many tales speaking of priest-kings who could trace their ancestral lines back to local deities. The Foujodel, a sort of citizens assembly, is also commonly mentioned. The spread of Irfan to the Fersi desert began near the beginning of the common era, primarily through trade with the First Dominion of Heaven in modern day Zorasan, and several Pardarian merchants settled in Mabifia and would write out literary descriptions of the societies they found. The area was named Siyahstan, or "Land of the Blacks", after the skin colour of its inhabitants.

Bahian consolidation

Irfan had been practiced among the Ndjarendie since the beginning of the common era, but had until the 8th century been more or less confined to the sedentary communities of the inner Boual ka Bifie. During the 8th century, these communities began to preach to their pastoralist brethren, acheiving several key conversions. Around 850 CE, Fakruddin Bâ was born within the Bâ Bolonda, receiving religious education from a young age. According to the Tarikh-e Māhruyān-e Siyahstan, a hagiographic collection of tales of Irfanic saints in Bahia, Bâ was blessed with prophetic dreams which from a young age had meant he knew he would lead to a new dawn for the faith in Bahia. The faith's emphasis on a community of believers was a key inspiration for Bâ, who in 998 CE would convene a council of prominent Irfanic clergy among the Ndjarendie and organise the formation of a Razzia state. The Founagé Dominion of Heaven was formed, with Bâ chosen as its Asardaki. The Founagé Dominion of Heaven quickly began offensives against non-Irfanic Sares, starting with those present upon the Boual ka Bifie before moving further south. While raids by pastoralist groups had occured before, they had usually been the result of disputes over grazing rights and included small bands originating from one Bolonda. The Founagé Dominion of Heaven therefore represented one of the first multi-tribal polities in Bahian history, and was one of the first to aim at territorial expansion and conquest as opposed to the previous order which had been more or less peaceful.

The Founagé Dominion of Heaven was initially able to make swift victories, as the Fetishist city-states possessed small armies and were unable to resist the might of the united Ndjarendie hordes. Founagé was able to unite the majority of the Boual ka Bifie under its rule by the death of Fakruddin Bâ, and under his successors made inroads into Inner Bahia. However, the rapid successes of the Irfanis caused a panic among the fetishist city-states, who feared the erosion of their own cultures and religious practices should the Irfanis be successful in subjugating all of Bahia under their rule. At Kaanmabe, in the Ouloumic highlands, a fetishist nobleman named Koyizo Nzorfu used his wealth to ensure the loyalty of a core of warriors and performed what could be considered a coup d'état. He then invited other Sares in his area to pledge their loyalty to him, in this manner uniting a small dominion which was able to raise enough levies to resist the Irfanic invaders. The success of Nzorfu at Kaanmabe marked the beginning of the decline of Founagé, and news of this victory and the system he had established spread across fetishist Bahia. What followed was a period called the "Great Bleeding", as Bahia was effectively consolidated from an assortment of city-states into larger Houregic states. From the basic principles established at Kaanmabe, Hourege would emerge over the next decades as the dominant system of social organisation in both Fetishist and Irfanic Bahia.

Houregic golden age

First contact with Euclea

Fatougole

Colonial Mabifia

Sougoulie

Kaoule

Socialist era

With the conclusion of the civil war, the Mabifian Section of the Worker's Internationale led Popular Liberation Front took complete power. However, the effects of the civil war had left Mabifia heavily damaged. Economic infrastructure such as roads and railways had been targetted by all parties, while mines and oil extraction infrastructure had been largely abandoned or damaged. To compound this problem, the flight of the colonial elite and much of the indigenous Bahian middle class both during the conflict and at the victory of the socialists had left a major skills shortage. Léopold Giengs, the first State President, faced a difficult task in restarting the nation's economy. He opted to seek help from abroad, inviting specialists from Kirenia and Chistovodia to the country in order to train local technicians. Farmlands which had been owned by Gaullicans, as well as those owned by local elites who had fled during the civil war, were seized by the state to be run as collective farms. Land was distributed to local communities in order to be run by localised councils called foujodes, which would in principle give every peasant land, housing and food to support themselves.

The difficulty of moving Mabifia towards a socialist society as envisaged by the more ideologically purist wing of the Mabifian Section of the Worker's Internationale was quickly evident, however. The population were largely illiterate and dependent on subsistence agriculture, with the fledgling industrial base created by the colonial administration in ruins. Giengs, a member of the more pragmatic wing of the party, quickly realised that the popular support for the socialists had been in their promise of land for all and an end to oppressive landowners as opposed to the promise of an industrialised classless society and opted to focus on this rural base as a means of consolidating the Mabifian Democratic Republic's hold on the country. A member of the Mirite minority, Giengs was unable to anchor his support upon the loyalties of an ethnic group and this forced him to take a highly cautious approach to administrating the country. Giengs took a lenient stance towards many elements of traditional Bahian society, aware that any strong repression of religious groups could destabilise the young state. However, Mabifia under Giengs was anything but free and Giengs presided over the creation of the Agence nationale pour la Défense de la Révolution, which was responsible for the suppression of all political opposition to the socialist government. Another key area of development was education, which was seen as a key element of ensuring successful socialism in Mabifia. Schools were constructed across the country, as well as universities at Ainde and Kangesare. These schools were tasked with "forming a revolutionary generation", and the content of their classes was highly politically motivated. Children were taught to love the party more than their own families and to oppose all traditions which were deemed un-socialist.

In 1950, Léopold Giengs passed away due to a cardiac arrest. He was succeeded by Fuad Onika, a younger military lieutenant colonel who represented the more hardline faction of the Mabifian Section of the Worker's Internationale. Onika viewed Giengs' cautious approach as cowardly and a betrayal of the true principles of the revolution, and began a major program to modernise Mabifia along socialist lines. His vision for a new Mabifia was based strongly on the creation of Villes nouvelles, new cities which would be centred on industrial production and take people away from their traditional lands in the hopes that they would be forced to abandon any remaining traditional beliefs or identities and instead embrace the melting pot of a Pan-Bahian proletarian identity. Many traditional leaders, such as the Karanes of the Ndjarendie and Mwami of the Barobyi, were killed even if they did not offer any resistance to the regime. In the same way, the ANDR were involved in the disappearances of many prominent Irfanic and Catholic clergypeople. The villes nouvelles were unsuccessful in destroying tribal and regional identities, but the melting pot of cultures combined with sense of dissatisfaction with the regime lit the spark for Djeli Pop to emerge as a musical genre. The rise of the United Bahian Republic saw initial interest from Mabifia, but tensions between the staunchly anti-revisionist Onika and the comparatively nativist Izibongo Ngonidzashe would mean that Mabifia rejected ascension into the union.

By the mid 60s, tensions with neighbouring Rwizikuru following the collapse of the United Bahian Republic had grown over the Yekumaviria, a province of Rwizikuru which had historically been under the influence of the axial Houregery in Kambou but which had been granted to Rwizikuru by Estmere following independence due to its Ouloumic population. In particular, Onika desired the sea access that possession of the area would grant as Mabifia was limited to a very small coastline. Fishing rights were another issue, as well as the potential presence of oil in the Maccan Sea. In 1968, these tensions boiled over and Mabifian forces invaded Yekumaviria. This war lasted just five months, with the Mabifian armed forces outnumbering their enemies and helped by the economic and military support of the Association of Emerging Socialist Economies, but saw high casualty rates for both sides. Mabifia would eventually be successful in this conflict, with the Community of Nations-backed Purple Line drawn up to demarcate a demilitarised border between the two states.

Despite victory in this war, Mabifia's economy was struggling under the weight of the socialist system and the costs of the war effort. Productivity rates had lowered in most areas, while the rural population who had been the backbone of the party's support felt attacked by Onika's policies of forced urbanisation. Even in the villes nouvelles, which had been intended to be the backbones of support for the regime, people were feeling disillusioned with the authoritarian nature of the state and the destruction of old traditions. News from Garambura, which was smuggled into the country, gave the population hope for democratic reforms. While the cult of personality surrounding Fuad Onika helped to glue together the state, his death in 1972 severely weakened the already struggling state. His successor, Soleïman Keïta, was a member of the reformist wing of the party and sought to ease back some of the more oppressive measures put in place by Onika. However, by this point tensions were so high that he only succeeded in precipitating the fall of the Mabifian Democratic Republic.

Second civil war

In February 1973, just months after Fuad Onika's state funeral, a disturbance took place at Iboïambou when a pirate radio station which broadcast banned songs by artists such as Honorine Uwineza was raided by the ANDR during a special broadcast to celebrate the singer's life 5 years after her death. The station was live as the raid occured, meaning that despite the best efforts of the secret police to make the raid discrete the operation was broadcast across the nation. As the studio was raided, radio disk jockey Farhad Nsengiyumva began to make inflammatory remarks and called for resistance against the socialist government. Nsengiyumva and the other members of the radio crew were eventually arrested and taken away in an unmarked military truck for trial. However, unlike other disappearances of opposition figures which usually involved a quiet abduction and retained an aura of untouchability for the state, this operation had been broadcast to the nation and had been very messy, in a way exposing the vulnerability of the regime. As rumours spread, the local police department claimed that Nsengiyumva and his colleagues had been arrested for counterfeiting, an obviously faked charge which did little to quieten discontent. Media in Garambura and other countries picked up the story, putting pressure on the Mabifian government to release the radio station's personel. "La musique n'est pas une crime!" ("Music is not a crime!"), the headline which appeared in the Gaullican newspaper Le Monde on the subject of the raid, was carried on placards outside Nsengiyumva's trial. Feeling threatened by the protests, which had attracted upwards of a thousand participants, the mayor of Iboïambou deployed military forces in the streets and put in place a curfew. While this temporarily stopped protests, the Nsegiyumva affair had been a sign to many dissidents that the regime was starting to falter.

Following the Nsegiyumva affair, disturbances and anti-regime protests became more widespread. While these remained largely peaceful, they continued to gain momentum as a way of expressing dissatisfaction with the economic downturn which was affecting the state. Food shortages were becoming widespread following poor harvests on the collective farms, and despite the propaganda of working towards a classless society, people noticed that members of the Mabifian Section of the Worker's Internationale were more able to get food than ordinary workers. In March, a protest in Kangesare over bread shortages turned violent after the Unités de mobilisation populaire, the MSWI's armed wing, opened fire on crowds in an attempt to suppress the protest. This triggered a riot, in which several symbols of the socialist government were defaced, and over 200 protestors were killed during the suppression of the unrest. Two days later, State President Soleïman Keïta declared a state of emergency and martial law for the entirety of Mabifia.

This news was heartening for opposition groups such as the Pan-Bahian Democratic Party and Organisation of Mabifian Irfani Brothers, which had been forced into exile by the socialist regime at the end of the first civil war. Several of these groups had military capabilities, and operated training camps in neighbouring countries. In June 1973, the leaders of these groups met in Port Fitzhubert and agreed to work together to depose the Keïta government, forming the Front for Unity and National Salvation. While this announcement was met with outrage from the Mabifian government, who accused Rwizikuru of being an agent of the imperialist powers, it gave hope to many Mabifians that change was possible. President Soleïman Keïta went overseas, visiting other socialist nations in order to shore up support in case of a civil war. While the border with Rwizikuru along the Purple Line was highly militarised and guarded by Community of Nations peacekeepers, Mabifia's long borders with the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran and Yemet were lightly manned and almost impossible to guard. Rebel forces began to cross the frontier, setting up advance bases within Mabifia's northern provinces. This took place in secret, allowing for a considerable buildup of rebel troops.

The civil war openly began in October, when a convoy of Mabifian soldiers was ambushed by rebels in the Fersi desert near the border with the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran. The Front for Unity and National Salvation claimed the attack, declaring via Radio Mabifie Libre that their forces had carried out the attack and killed 30 government soldiers. The news came as a surprise to the Mabifian Democratic Republic's military command, who had vastly underestimated the strength of the opposition forces. Smaller attacks took place across the Boual ka Bifie, as both smaller rebel cells and lone wolf attackers began to take up the rebel cause. In response, the government called for the mobilisation of almost 100,000 reserve soldiers and began operations to seek out and destroy rebel emplacements in the country's north. The violence remained low level, but was escalating rapidly as rebel attacks grew more and more open. By the end of November, rebel forces controlled several significant border towns on the Pardaranian border, allowing for a far easier supply route. It is alleged that Pardaran volunteers such as the Black Hand were involved in these operations, though this is denied by the Zorasani government to this day.

In early 1974 a new front was opened in the conflict, as covert shipments of arms made their way into the hands of dissident cells within the Ahirengeïe. These militants began an urban guerilla campaign, targetting government and military emplacements in Iboïambou and other cities. These actions lowered confidence in the regime, which was already sagging, and though the urban cells were mostly defeated by mid 1974 the damage they did to the morale of much of the regime was large. During this time, the rebels had made significant progress in the Fersi desert and Boual ka Bifie, to the point where the regime's control was weak outside of urban areas. However, in late 1974, the unity of the opposition took a major blow when the Mirite-led People's Coalition for Makanian National Sovereignty broke off from the Front for Unity and National Salvation in its goal of seeking independence for Makania. This led to a three-way conflict in the north of the country, slowing the rebel advance and allowing the central government to paint the rebels as a destabilising force who sought to divide Mabifia under colonial interests.

The situation took a turn for the worse for the socialist government in May 1975, after a large group of rebels who had trained in Rwizikuru managed to cross the border and get into the jungle of the highlands. These rebels were difficult to track due to the dense and difficult terrain and began to initiate offensive operations in the mountainous areas of eastern Mabifia. This presented a significant threat to the regime, as these rebels were close to many of the regime's key urban centres. Many from the cities left their homes in order to join the rebels, swelling their numbers and allowing them to mount increasingly large offensives. Zandou, the capital of Masamongo department, was the first significant urban area to be taken by rebel forces, a key propaganda victory. Defections in the armed forces became increasingly common, especially among the volunteer troops, leading the regime to lean on the more strongly partisan Popular Mobilisation Units. The war was brutal on both sides. Known members of the Mabifian Section of the Worker's Internationale were often shot without trial by rebel soldiers, while suspected rebels often faced the same fate. By the end of 1975, the rebels controlled swathes of territory in the northwest and east of the country, while the Makanian separatists held the bulk of Makania. Despite this, the regime still held most of the core urban areas of Mabifia.

1976 is often referred to as the year which broke the Mabifian Democratic Republic. As the rebels advanced across the Boual ka Bifie, they neared the city of Kangesare. Kangesare was the second largest city in Mabifia, and the largest in the Boual. In May, Lieutenant-General Hassan Babangida, who was the head of over 60,000 soldiers, announced his defection to the rebel cause. An ethnic Ndjarendie, Babangida hoped to secure a better position for the Ndjarendie in a new government and to protect his own interests, but was also motivated by his own personal support for a democratic regime. With his defection, the rebels were able to quickly take Kangesare by July and began marching inwards towards the regime's centre in Gollobesare. However, fractures began to show in the rebel coalition, as Irfanist fighters in the north of the country fired upon democratic fighters as the two main groups started to fight over who would rule over the country. At this point, the government were unable to take advantage of these rifts and began fortifying the southern urban centres in expectation of attack. Throughout 1977 the rebels continued their advance on the capital, and by the end of the year the socialists controlled just the capital city. Fighting between the different rebel groups was sporadic but constant, as while the leaders of each group publicly supported the united front they secretly hoped to be the sole ruling group at the end of the conflict. The kingmaker in the dispute was to be Hassan Babangida, who appeared with the leadership of the Mabifian Patriotic Movement and pledged his support for the return of democracy.

By 1978, the socialist government controlled only Gollobesare and was starting to lose hope. Keïta called for negotiations, but was rebuffed by the rebels. On the 13th of May, Keïta and several other key regime figures fled to neighbouring Dezevau with a large sum of money. The MDR exploded in on itself, with officers across the country laying down arms and surrendering to the coalition. Rebel troops entered the capital and began to tear down visible symbols of the regime, wantonly killing those associated with the regime and plundering shops. A transitional government was announced, with the heads of the major rebel factions serving as a collective leadership, and the Community of Nations were invited into the country to help restore order and build a new government.

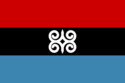

Democratic reforms, Makanian conflict and modern day

The transitional government was quick to dismantle the state apparatus put in place by the old socialist regime. Babangida's Provisional Unity Government, formed of the heads of the major rebel factions, organised a cabinet and scheduled elections for the following year. The government was able to present a united front for the first months, selecting a new flag and Coat of Arms in order to remove the vestiges of socialist rule, as well as renaming Gollobesare to Ainde alongside many other cities which had been renamed during the socialist regime. However, behind the public handshakes and unity, the coalition was extremely fragile.

Geography

Climate

Environment

Politics and Government

Mabifia is a federal presidential republic, where a President serves as head of state. The current President is Mahmadou Jolleh-Bande, who was first elected to the position in 1997 and has since won re-election in 2004, 2011 and 2018. The powers of the President are delimited by the constitution and are expansive. The President is able to create policy, is in charge of the appointment of government officials including the Premier, represents the country overseas, and is the head of the Mabifian Armed Forces. The person of the President is protected, with insulting the president illegal.

The legislative branch is represented by the Parliament, a bicameral legislative assembly composed of the 56 member Senate and 350 member National Assembly. The Senate serves as an upper house and is composed of two representatives from each Department. The National Assembly is comprised of elected officials, who are elected using a first past the post system. To be accepted, a bill must be passed by both houses. The judiciary branch is represented by civil and religious courts. These are theoretically independent, but due to corruption and the unofficial influence of traditional elders over their decisions they are widely seen as being instruments of the government.

Mabifia is legally an open multi-party democracy which guarantees freedom of speech and freedom of the press. While multiple parties do exist and contest elections, the electoral process is widely deemed to be flawed. This is due to widespread corruption, vote fixing, intimidation of political opponents and even politically motivated killings and violence against journalists. These problems are prevalent rural areas, with the democratic process in many urbanised departments being far more open and reliable.

Military

The Mabifian Armed Forces constitute the military of Mabifia. It consists of the Mabifian National Army, the Mabifian National Air Force, Mabifian National Navy, and several paramilitary groups such as the Sans-Éclipses. With a total of 490,702 members counting active, reserve and paramilitary personel, Mabifia's armed forces are the largest in Bahia. Despite their size, their equipment is highly outdated and reliant on surplus weaponry from other nations. The armed forces are also weakened by corruption and nepotism, with promotions often made on the basis of ethnic or geographic background and loyalty as opposed to performance.

The head of the Mabifian National Armed Forces is the President, but this position is purely ceremonial. In practical terms, the Armed Forces are commanded by the Combined General Staff of Mabifia. This is a council of the highest ranking officers in Mabifia, including the heads of the Army, Navy and Air Force. There is no conscription in Mabifia, service is voluntary. The Mabifian National Armed Forces have seen service within the Makanian Conflict, and are accused of war crimes in this conflict.

Foreign Relations

Since the fall of socialism at the end of the Second Mabifian Civil War, Mabifia has pursued a balanced foreign policy. Mabifia is an active supporter of multilateralism and heavily involved in solidarity movements in the developing world. It was a founding member of the Congress of Bahian States and actively participates in all of the organisation's projects, with Pan-Bahianist goals being a major part of its relations with its neighbours. Mabifia has repeatedly stated its interest in the creation of a Bahian customs union and common market, though it does not support political unification. It is also a member of the International Forum for Developing States, Community of Nations and International Trade Organisation.

In terms of bilateral relations, Mabifia has close ties with its former colonial power Gaullica thanks to foreign aid projects and support during the civil war. These ties are strained by authoritarian trends within the Mabifian government. In recent years, Mabifia has reached out to the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics and Xiaodong for economic support as Euclean support has diminished, but has not joined the Rongzhou Strategic Protocol Organisation and still maintains relations with COMSED nations such as Senria and Mathrabhumi. Relations with Rwizikuru have been historically tense due to border disagreements following the Mabifia-Rwizikuru War, but these have warmed in recent years following Rwizikuru's dropping of claims on Yekumavirira and the reopening of borders. Mabifia maintains a rocky relationship with neighbouring Djedet, which it accuses of funding opposition groups in the Makanian Conflict.

Economy

Before gaining independence from Gaullica in 1942 Mabifia was a key producer of gold and cash crops such as sugar and cocoa which were exported to Euclean markets, predominantly mainland Gaullica. These industries were owned by Gaullican landowners, who fled the country in the civil war which followed independence and the announced nationalisation of all economic means of production by the Popular Liberation Movement government which took over. This led to a massive decrease in agricultural output, crippling the Mabifian economy. Agricultural production levels only reached pre-independence levels in 1950, helped by Swetanian economic advisors. During the Neo-Sâre Campaign, agricultural production skyrocketed while other industries suffered, before being all but destroyed during the Mabifia-Rwizikuru War and Second Mabifian Civil War. Following the end of the war, other industries were prioritised over agriculture but the wars were extremely damaging and Mabifia has not fully recovered.

The petrochemical industry is the largest earning and most developed economic sector in Mabifia, thanks to copious petroleum reserves within the region of Makania. This petrol is a source of conflict in the region. Crude petroleum accounts for roughly 50% of state revenues, and with NUMBER barrels of crude oil exported each year Mabifia is the largest producer and exporter of oil in Bahia. This oil is transferred by pipeline to the Banfuran coast, from where it is exported to overseas markets. Other important sectors include gold and other precious minerals, and crops such as cocoa, sugar and coffee. Subsistence farming is widespread and emplys the largest number of workers of any economic activity. Mabifia maintains close economic ties with its neighbours as part of the Congress of Bahian States, based on both ideological and practical considerations.

The main issues that face the Mabifian economy stem from its political situation. A major problem is corruption, which is ever-present at almost every level of Mabifian society. This has led to a form of crony capitalism which some observers have labelled as neo-Hourege due to the predominance of family-based control and integration within local power structures. Another issue is internal instability, as the Makania region which accounts for 85% of Mabifia's oil reserves is the location of an insurgency which aims for independence for the Mirite people. Much of the nation's industry was completely destroyed during the five years of civil war that raged between 1973 and 1978. These factors have resulted in Mabifia's GDPPC being the lowest in the Bahian region and one of the lowest in the world.

Energy

Industry

Infrastructure

Transport

Transport in Mabifia is generally difficult, thanks to a general lack of developed infrastructure. Rail transport in Mabifia is highly limited. The country has two railway lines, the Adunis to Mambiza Railway and a connection between this line and Ainde. The country's rail infrastructure is largely based upon colonial construction and was decimated during the civil war with little reconstruction. There are plans to construct more railway lines in conjunction with neighbouring states, however, these plans are fraught due to the high costs of construction which are not affordable for the state. Construction of a Banfuran Coast Railway was started in 2014 but thanks to embezzlement of funds by project managers the project has stagnated.

The Mabifian road network suffers from many of the same problems as the rail network, with poor infrastructure rife. Aside from a network of toll roads constructed with the help of Gaullica which connects major cities and the roads that service the Zorasani border, roads in Mabifia are of a generally low quality. Only 10% of the total road surface is tarred, leading to issues particularly in the wet season when roads can be washed away. Banditry is a major problem in rural areas particularly the north, while police roadblocks often serve as collection points for bribes and do not help with security. Banditry is especially a problem within the unstable Makania region, with most nations issuing travel warnings for travel here. Intercity bus companies connect all major cities, but the most widespread method of long-distance travel is the Mabaranou. These are privately owned minibuses which run itinerant journeys between different cities.

The domestic aviation market in Mabifia is almost nonexistent, with limited amounts of charter flights linking the larger cities. These primarily serve foreign tourist groups who wish to avoid the dangers of overland travel and are highly irregular. The sole airline company based in Mabifia is Mabifian Airways, which serves as the flag carrier. There are flights between Ainde and other major Bahian and Coian airports, as well as connections with Verlois. Ainde is the largest port in Mabifia, handling 56% of the nations exports.

Demographics

Ethnic Groups

Mabifia is a massively diverse nation, with hundreds of different ethnic groups each possessing their own rich cultural heritage and traditions. Unlike many nations, Mabifia does not have one singular ethnic group which forms the majority, nor indeed one family of ethnic groups which makes up a majority of the population. The largest ethnic division are the Ouloume peoples, who form roughly 36% of the population of Mabifia. They are located in the southeast of the nation, and are divided into a highly diverse range of groups. The largest Ouloumic group are the Barobyi, who make up an estimated 18% of the population of Mabifia. Other significant groups include the Bahoungana at 8% and Ekole at 4%, as well as a population of veRwizi who form 2%. The remaining Ouloumic population, which is estimated to be around 4% of the nation's total population, are highly diverse and split into many smaller groups.

The second largest group in Mabifia are the Boualic peoples, who inhabit the Boual ka Bifie and Fersi desert. Boualic peoples occupy 31% of the nation's population. The largest Boualic group is the Ndjarendie, who at 24% are the largest singular ethnic group in Mabifia. Due to their historic importance during the Bahian Consolidation and in the following states such as the Founagé Dominion of Heaven and Kambou Empire, the Ndjarendie have had a major cultural and linguistic influence on Mabifian society and dominate much of the nation's politics. Other Boualic groups, such as the Mangi and Doudagi, mak up anothet 7% of the population.

Other important ethnic groupings include the Bélé peoples, a family of ethnic groups which comprises of the Saban, Anana and several other groups. The Bélé have had an important influence on Mabifia through the adoption of the kora, the traditional instrument of the Djelis. The Machaï peoples, located in Makania, are another important ethnic group. They make up 9% of the nation's population, a figure dominated by the Mirites. Also significant are the Sewa, the largest ethnic group in the Boual region who remain predominantly Fetishist, at 4%, Ziba peoples from neighbouring Dezevau at 2%, and Mourâhiline at roughly 2% of the population.

Education

Religion

Mabifia is a relatively religiously homogenous nation. The dominant religion is Irfan which is practiced by three-fifths of the population, with the rest of the population either adhering to Sotirianity (35%) or to traditional Bahian fetishism. Irfan plays a dominant cultural and political role in the nation, with religious freedom being restricted. This is more prevalent in rural areas, where Irfanic elders and officials enforce the practice of the faith. Irfan is the majority religion in all areas of the country save for several Ouloume-majority coastal departments where the Sotirian population is concentrated. Sectarian violence is common in Mabifia. This has manifested itself in the many atrocities committed during the First and Second Mabifian Civil War against the Sotirian and Fetishist minorities.

Mabifia was originally dominated by Bahian fetishism, a loosely associated group of religions based around nature gods and idolatry. Sotirianity arrived in the 300s from Makania, with the exodus of the Mirites bringing the fouth southwards. Irfan was first brought to Mabifia in the 800s with the rise of the Founagé Dominion of Heaven. Over the next centuries numerous Ndjarendie states invaded across Bahia, triggering the Bahian Consolidation and bringing the Irfanic faith with them. Irfan has remained dominant ever since, adopting elements of local traditions and syncretic elements which differentiate it from traditional Badawiyan Irfan. During Toubacterie Solarian Catholicism was introduced, attracting conversions primarily from the Ouloume minorities. These demographics were further changed at the end of the Mabifia-Rwizikuru War which saw massive population exchanges of Irfanics and Sotirians between the two states.

The Irfanic population are primarily followers of the Laoulïabe sect. Laoulïabe Irfan is related to the traditional Asha school, which it emerged from, but its separation from the traditional Irfanic heartland in Zorasan and influence of local traditions resulted in several theological differences. There are also significant numbers of practitioners of traditional Irfan, and several revivalist groups have a presence in the country. Despite Orthodox Sotirianity's historical roots in the region, the majority of the Sotirians in Mabifia follow Solarian Catholicism which was introduced during the colonial period. In recent years several Amendist groups have started missionary work, however these groups are very unpopular. The Fetishist community are often accused of witchcraft, which is widely believed in in Mabifia and criminally prohibited.

Culture

Music

Mabifia has a rich tradition of musical expression, dating back to its early history. This historical richness and breadth of artistic styles has resulted in Mabifian music being extremely diverse and varied. The most typical musical style associated with Mabifia is that of the Djeli, a caste of artesan-slaves under Hourege who operated in a similar manner to the bards of medieval Euclea. Djeli music was often instrumental, a genre known as Gallol, or lyrical, called Gimol. Gimol songs usually followed poetic structures and dealt with themes such as love (Gimol-giggol) or praise upon heroic figures or religious saints (Gimol-yetoode), and would sometimes accompany Irfanic group meditation sessions. The Djeli were highly respected across Bahia, despite their slave status, as it was through these songs that much of Bahia's early oral history was transmitted. The Djeli traditionally used instruments such as the kora, bongo drums, balafon and other such instruments.

Under Toubacterie, the Djeli were officially granted manumission, but found less audience for their talents as the Eucleans preferred their own musical traditions. Whilst some anthropologists and historians did seek to obtain information from them in order to preserve it for posteriority, it is believed that much cultural knowledge was lost in this period. There were some efforts to bring orchestral music to Mabifia, and this attained some success among the native middle class and métis populations, but these styles were unable to gain widespread acceptance due to the intricacy of orchestral preparations and formalised musical notation which ran counter to the musical traditions of Mabifia. It is believed that the descendents of Mabifian Djeli shipped to the Asterias as part of the Transvemens Slave Trade were responsable for the development of genres such as Jazz there, as it shares some similarities with the traditional Bahian styles of music.

The Mabifian Democratic Republic was repressive of music which was seen to condemn the regime, as well as traditional musical styles as their often religious and mythical themes were seen to be remnants of non-socialist culture. This artistic repression, combined with the policy of Fuad Onika's villes nouvelles which created a melting pot of different cultural backgrounds within small industrial towns, laid the scene for the emergence of Djeli pop as a musical genre. Djeli pop, which carved out a unique niche in the musical world with its incorporation of both traditional Djeli instruments and modern instruments such as the electric guitar and charged political lyrics, would go on to become one of Mabifia's most influential cultural exports. Artists such as Honorine Uwineza became household names both in Mabifia and abroad, with the genre going on to influence music across Bahia. While Djeli pop was restricted in Mabifia and Uwineza herself was killed due to her political activism, it would go on to serve as a basis for much of Mabifia's later music.

In the modern period, traditional Djeli pop has been replaced in many areas by newer genres which built off of Djeli pop's success. Modern Mabifian music often makes heavier use of electronic technology, though traditional rythyms are still a key part of the musical scene. Genres such as rap and electronic dance music have grown in popularity, with Drum and Bass music especially gaining a widespread audience in urban areas. Artists such as the Mabifian-Gaullican singer Djeïne combine multiple styles in their music, often singing in Gaullican as opposed to traditional tribal languages in order to expand their audience. Religious music is also highly popular, with radio stations playing only gospel or Irfanic Gata.

Cuisine

Mabifian cuisine is highly varied depending on the geographic region, as the availability of foodstuffs can differ wildly. Mabifians commonly eat two meals a day, a small breakfast before sunrise and a large meal in the evening after sunset. This is due in part to religious practicality, following the sunrise and sunset, but also due to the need to work during the daylight hours as much of the workforce works in subsistence agriculture which is done primarily by hand. A typical meal consists of foufou, a doughlike substance made by grinding cocoyam, manioc, plantain and other fibrous foodstuffs such as flour with water, and soups made with groundnut, vegetables and palm oil. Meat and fish are rarer but still play an important role in Mabifian cuisine. A common snack is Boucougo, which are roasted at the side of the road and sold in a cornet of newspaper.

Cutlery is not widely used, especially in rural areas. Instead, Mabifians eat using foufou or with flatbreads. The right hand is customarily prefered. Snacking is widespread during the day, with streetside vendors selling brochettes and fried dough for very low prices. The widespread practice of Irfan has resulted in a very low consumption of alcoholic beverages, with drinks such as hibiscus tea being preferred instead. Despite this, palm wine and other homemade alcoholic beverages are common in the Ouloume majority coastal areas where Irfan is less dominant.