Mardin Isles

Republic of the Mardin Isles Poblaċt na hInsí Mairdinde | |

|---|---|

Motto: "Bás nó saoirse ċoíċe" Death or liberty, forevermore | |

Anthem: Fionnġall "The fair-coloured man" | |

| |

| Capital | An Ráṫ |

| Official languages | Mardic |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

| x | |

| Aonghus Ó Lunaigh | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Senate | |

| House of Deputies | |

| Independence from Template:Country data tir Lhaeraidd | |

• Declared | 22 March 1926 |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 1,620,000 |

• 2015 census | 1,575,602 |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $90.8 billion |

• Per capita | $57,640 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $76.9 billion |

• Per capita | $48,810 |

| Gini (2017) | 33.2 medium |

| HDI (2017) | 0.906 very high |

| Currency | Mardic bonn (MAB) |

| Time zone | AST -2:00 |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +360 |

| Internet TLD | .ma |

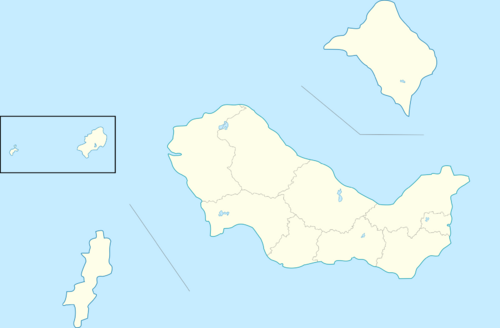

The Mardin Isles (Mardic: Poblaċt na hInsí Mairdinde) is an island country consisting of an archipelago in Western Asura. It shares maritime borders to the east with tir Lhaeraidd and to the north with Vrnallia. With a population of around 1.6 million, it is one of the smallest sovereign nations in Aeia. The archipelago consists of three main islands; Lower Mardin, Upper Mardin and Inis Uí Breasail as well as a set of smaller islands further west of the main isles. Around 85% of the population lives on Lower Mardin which is where the three largest settlements are located, including the capital city An Ráṫ. The official language is Mardic, which is widely considered to be a dialect of Mawr Lhaeraidh.

The archipelago gets its name from the Mairtine, a Maíreidh people who arrived from the Asuran continent around 5,000 BC having been left virtually uninhabited for thousands of years following the Ice Age. They developed a distinct Mardic culture which was later influenced by Lhedwinic and Vrnallian raiders who settled during the 7th to 9th centuries. By 1000 AD, the Mardin islands were divided by several kingdoms and provinces which competed against each other for dominance and power, with unity rarely occurring.

The isles were invaded by tir Lhaeraidd during the early 15th century and were swiftly amalgamated into the Teyrnas. The Mardin Isles remained an integral part of the kingdom for over 500 years, during which the Old Mardic language was reformed to be in line with Mawr Lhaeraidh and the pagan beliefs of the majority of Mardics were converted into Derwyedd. The archipelago were developed as a naval and trading port, as well as a major agricultural hub thanks to the extremely fertile land.

During the latter half 19th century, discontent for the union grew and a home rule movement grew in popularity. Home Rule was rejected by the Teyrn in 1893, prompting backlash across the isles. When tir Lhaeraidh entered the Great War in 1897, an independent republic was declared in An Ráṫ which was unrecognised by any sovereign state. Following the conclusion of the war, the republic was quelled and home rule was finally granted. Desire for independence grew which culminated in negotiations on the Mardin Isles' future between separatists who controlled the regional assembly, and representatives of the Teyrn. A referendum followed in 1926 which was passed decisively, and a republic was declared on 22 March 1926, following the withdrawal of Lhaeraidh forces.

History

Early history and Maíreidh settlement

The earliest indication of settlement on the isles is believed to have been around 20,000 BC, when it is assumed that settlers arrived from mainland Asura during the Upper Paleothic era. Although there is very little known about these people, it is assumed these people were hunter gatherers, like many other groups around the continent during this time period. Much of the isles were covered in ice at this time, and climate change could have been a major factor in the survival of these groups as it is believed that many of the settlers migrated away from the islands around 15,000 BC.

Maíreidh migrants arrived from tir Lhaeraidd around 5,000 BC and settled initially on the eastern coast of Lower Mardin. This group were known as the Mairtine people, from which the isles get their name today. They remained closely linked both culturally and linguistically for many centuries however the language began to develop independently. By about 800 BC, several petty kingdoms existed.

Although Mardinian tribes and kingdoms were not as powerful and in many cases not as advanced as other civilisations at the time, society and the hierarchical structure were strongly entrenched and in many respects highly sophisticated. Mardinian society was largely centered around powerful kin-groups known as clans or fine. The petty kingdoms and tribes that had formed on the isles had been formalised into túatha (plural of túath) which were centered around single kin-groups. Prior to the beginning of the consolidation of túatha into larger polities, they were largely independent of each other and were frequently at war with each other.

Túatha were traditionally ruled by a king, the head of the kin-groups. Not all people within a túath were part of the kin-group, indeed most were freemen or serfs and the population of most túatha are thought to have rarely exceeded 10,000. The king of a túath was elected by a process known as tanistry, where members of the kin-group would elect a new king at an assembly following the death of the preceding king. The title was usually handed down to the eldest male child of the former king, although brothers and cousins of the king were also commonly selected. Although it was possible for a female to be elected, these instances were rare owing to the higher status of men in Mardinian society. Below the king and the wider kin-group were the comsid-dána, a group made up of jurists, craftsmen, poets, druids, scholars and bards. The comsid-dána acted as advisers to the king. The fianna were the warrior bands of the túatha. They were highly respected in Mardinian society.

Between 100 AD and 500 AD, tuatha began to form mór-tuatha often by joint consent but also commonly through conflict. As a result, many kin-groups merged with each other to form much grander dynasties in a bid to consolidate larger influence and power within its respective region. Some kin-groups became more significant than others and therefore many fell into obscurity and irrelevance. Soon enough, the mór-tuatha began to merge themselves with each other forming provinces (cóiced).

Vrnallian and Lhedwinic settlement

The first wave of modern non-Maíreidh migration came from the north in the 8th century when Vrnallian raiders settled on the mostly forested and unused Upper Mardin, settling along the northern tip of the island. Up to this point, the Mardinian kingdoms that had developed were mostly sparsely organised as the concept of clustered settlements had yet to catch on. The Vrnallian settlers are often credited with establishing the first town settlement on the Mardin Isles, named Lykkábóse, which is now the small port town of Cois Cloch.

The first Lhedwinic raids took place towards the late 8th century and early 9th centuries. These were carried out by the Dalish people coming from Crylante and Glanodel. They pillaged many settlements along the northern coast of Upper Mardin and later Mardinian provincial lands along Lower Mardin's shores, enslaving many of the natives along the way. Intriguingly, they left the Vrnallian settlements alone.

It wasn't until the mid 9th century that the waves of Lhedwinic raids turned into settlement, primarily setting up settlements along the Upper Mardin coast. These settlements were well organised and quickly established themselves as influential territories over the native Mardinian kingdoms. One of the major characteristics of the Dalish settlements was the introduction and spread of the Trúathi religion which was enforced in the settlements it had taken over, and encouragement of it on the Mardinian people, who were almost unanimously pagan.

The Lhedwinic settlers began to mutually interact and trade with the native provinces and kingdoms. Towards the end of 9th century, the Lhedwinic settlements had begun to speak the Old Mardinian language as their primary language. The influence of Lhedwinic settlers on the Old Mardinian language is still reflected today, with many words used today originating from Old Lhedwinic. Rivaling Mardinian territories would often consult the Lhedwinic territories for manpower in conflicts. These changes collectively initiated the beginning of the formation of a syncretic Lhedwin-Mardinian culture.

Lhaeraidh rule (1422 CE - 1926 CE)

The nation of tir Lhaeraidd maintained complete political and military control over the Mardin Isles from 1422, when Teyrn Harwyn V completed his conquest of the isles, until 1926 when a series of democratic secessionist movements successfully negotiated their independence from tir Lhaeraidd. Lhaeraidh rule was initially characterised by a period of oppressive and militant intrusion which included the construction of round-forts and castles by the Lhaeraidh nobility as a means of controlling the subjugated populace; by 1430 under the rule of Harwyn's successor Tyrone III the vast project of meticulous accounting of all goods and property in the land was completed in the form of the Cuntasaíochta Mardinaidh and from this point on the systems of Lhaeraidh control became more subtle in nature. Following this Lhaeraidh rule over the Mardin Isles is largely considered to have been relatively benign, particularly by comparison to the foreign hegemony witnessed elsewhere in Asura at the time. The native nobility were given the opportunity to collaborate and while those who didn't found themselves stripped of their lands and otherwise persecuted the new Lhaeraidh nobility's treatment of the common folk was arguably better than had previously been the case. Over the succeeding century the Lhaeraidh would introduce a uniform system of laws in line with those seen in tir Lhaeraidd proper, and the Isles would see a period of peace and stability not previously witnessed.

Origins of the Lhaeraidh Conquest

In 1418 CE Teyrn Harywn V of tir Lhaeraidd began the process of amassing funds, resources, and manpower in order to capture the Mardin Isles. Harwyn's motivations for this are unclear although contemporary accounts give a number of possible reasons. Even during this politically fractious stage in their history the isles remained a key trading hub with its harbours offering safe havens for merchant vessels and pirates alike; indeed it could have been the presence of pirates and raiders which finally spurred Harwyn into action. Another reason given is one of prestige; the Lhaeraidh crown had not indulged in the large scale expansionism of other nations, nor had it participated in many significant wars which could prove its place in history. The general consensus however is that the motivation for the conquest was principally economic. In March 1420 CE Harwyn led an army of approximately twenty thousand across the sea, where they landed in the eastern reaches of the Mardin Isles, initially unopposed the army set up an extended fortified camp and began foraging for supplies. The first engagement of the conquest took place on 2 April 1420 when the local clansmen and nobility rallied a large force to oppose the Teyrn.

Preparations for the Lhaeraidh conquest were, by the standards of the time, extensive. Tir Lhaeraidh at the time was ruled rule a system of plutocratic feudalism which meant that armed forces had to be raised by the plutocracy in lieu of their monetary payments to the crown; this combined with the fact that almost two years had been spent raising and equipping an army meant that the expense of the enterprise was vast and the preparations laid the groundwork for what would later become Rí-Airm during the 1542 reforms. The majority of the Teyrn's soldiers were infantry, with formations centring around heavy infantry known as Gallóglaigh. The heavy infantry were then supported by light infantry known as Kerns who were typically armed with light spears and javelins, and the now famous Lhaeraidh Longbowmen. The Teyrn himself had raised and armed an elite core force of approximately one thousand men who were heavily armoured and equipped with spears and shields. The army was also notable for a contingent of light infantry known collectively as the Fianna, who were essentially hangers on and glory seekers fighting in the hopes of elevating their position through deeds of bravery.

Lhaeraidh military strategy and military endeavours had become a finely honed art. The climate and terrain of the Mardin Isles was well suited to Lhaeraidh warfare and the lack of heavy cavalry was offset by the fact that the Mardic forces had very limited cavalry themselves. Further the Mardics lacked any answer to the range and power of the Lhaeraidh Longbow. All of this the Lhaeraidh commanders were well aware of; they had seen the efficacy of massed ranks of longbowmen against heavy cavalry in the past and the Mardians had no such cavalry, they would have to close the gap on foot exposing them to a withering hail of arrow fire. This would typify the Lhaeraidh strategy throughout the war, with the Teyrn and his Warlords sending forward archers and Kerns to harass the enemy and then holding the line rather than advancing.

Conquest of the Isles (1420 - 1422)

Contemporary historic accounts of the process of conquest and subjugation by the Lhaeraidh are scant due to the lack of centralised written record keeping in the Mardin Isles at the time. Most of the information scholars have relating to the two year period of conquest come from Lhaeraidh sources mostly in the form of bureaucratic paperwork; while actual accounts of the battles themselves are limited to folk tales and music in the bardic tradition. The National Archives in tir Lhaeraidd contain hundreds of books and scrolls detailing every mundane aspect of the campaign from how many participated and their names, down to the weapons and equipment they were issued and the supplies that were sent. Detailed reports of specific battles however are scarce, even though a well preserved monthly record of the campaign's casualties does provide some insight.

Bardic poems and traditional stories of specific battles within the conquest do exist, mostly focusing on the deeds of the Fianna and the Teyrn. However there is no written historical evidence to corroborate these stories and only very scant archaeological evidence. What is known is that in October of 1422 the Teyrn gathered his forces and the remaining Mardic nobility and made them swear allegiance and agree to pay homage in a grand ceremony in what is now the city of An Ráṫ. According to the Lhaeraidh records, which do not include the Fianna, a total of eight thousand two hundred and seven soldiers died from the Lhaeraidh forces during the conquest with a total of thirty five thousand three hundred and twelve soldiers fighting under the Teyrn's banner throughout the campaign.

Early Lhaeraidh Rule (1422 - 1455)

Upon establishing Lhaeraidh dominion over the Mardin Isles Teyrn Harwyn initiated the process of consolidating the power of the Lhaeraidh Crown over the territory; the earliest stages of this process were considered to be punitive and consisted of transplanted Lhaeraidh nobility establishing ringforts, tower forts, and castles while those Mardic leaders who had pledged fealty willingly were propped up and encouraged to do likewise. Priests from the Lhaeraidh mainland flooded the isles along with large merchant interests and peasants who were resettled in considerable numbers to the larger coastal towns of the eastern isles. Harwyn did not survive to see the completion of this process, and his son Tyrone III would defer rule of the Isles to an appointed leader known by the title Tiarna na nOileán (Lord of the Isles) who served as viceroy of the Mardin Isles. The first Lord of the Isles was Rónáin Ui'Oisean who established his fief as Tiarna na nOileán (Lordship of the Isles) and though he held far greater executive power than the Diúca (Dukes) of the mainland he was never elevated to that rank, nor would the 'Lordship' ever gain Ducal status.

Pre-independence

Post-independence

Geography

The archipelago of the Mardin Isles consists of three main islands – Lower Mardin, Upper Mardin and Inis Uí Breasail. This primary group within the archipelago lies in the North Sea, directly to the west of tir Lhaeraidd and to the south of Vrnallia. The Aodh Islands are the fourth group of islands located further west from the main archipelago. There are also a number of much smaller islands along the coasts of Lower Mardin and Upper Mardin, the vast majority are uninhabited.

There are several mountain ranges on Lower and Upper Mardin, generally in the centre of the islands. The highest point in the Mardin Isles is Tua Chulainn at 1,454m in the Staca Beatha mountain range, which straddles the border of Lower Mardin's five most westerly counties. Sliabh Nessa on Upper Mardin is the second highest peak, at 1,327m. The coastal and midland border areas of Lower Mardin are generally quite flat with some hills and cliffs, especially in the north-east in Eiscir and along the west coast. Upper Mardin is relatively the same albeit with more cliffs and higher terrain in the north-west. Inis Uí Breasail is more hilly and rugged compared to the two larger islands in the archipelago.

The Mardin Isles has a number of rivers, although they are small and all drain into the sea. There are four natural lakes, three on Lower Mardin and one on Upper Mardin. In addition, two artificial lakes have been created in Corr an Ab and An Ráṫ county respectively. There is also a crater lake on Aodh Mór in the Aodh Islands.

Formed from volcanoes, the Aodh Islands lie much closer to the mid-Opalian ridge where the Asuran and Vestric tectonic plates move away from each other. The proximity of this boundary to the Aodh Islands, and to the Mardin Isles as a whole, means that the islands can be prone to seismic activity although major earthquakes have been rare.

Most of the Mardin Isles' population is concentrated in cities and towns either established on a river or on the coast. Approximately 85% of the population lives on Lower Mardin. The largest city is An Ráṫ, with a population of around 375,000. The second biggest city is Dún Carn in Corr an Ab with a population of just over 100,000.

Climate

The Mardin Isles lies within the temperate zone and with the exception of the Aodh Islands, the entire archipelago observes a similar climate with milder weather year round. The summers are generally warm, with average temperatures between 18°C and 23°C in the summer and between -1°C and 3°C in the winter. The Aodh Islands has a slightly more warm and humid climate, thanks to its position further out into the ocean. The highest ever temperature recorded in the Mardin Isles was 35.4°C (95.7°F) in the town of Caisleán Tréan in Corr an Ab in 1958. The coldest recorded temperature was -24.7°C (-12.5°F) in Ros Ceann on Upper Mardin in 1903.

The climate is defined as being a temperate oceanic or marine oceanic (Aerh Cfb, similar to its closest neighbours Vrnallia and tir Lhaeraidd. The milder weather is influenced in part by warmer ocean currents from the west, while the strong bouts of continental cold weather in the winter arrives from the east.

The Mardin archipelago is well known for its high levels of precipitation with heavy rainfall particularly year round, with snow persistant in the winter. The high levels of rainfall mean that agricultural land is very fertile and ideal for growing a ride range of plants and foods.

Nature

Politics

The Mardin Isles is a unitary republic under semi-presidential system of government. President Ruaidhrí Mac Neachtain is the head of state while Prime Minister Aongus Ó Lunaigh is the head of government. The Mardin Isles has been a republic since its independence in 1926. The Mardic Constitution was originally written in 1926 and modified ahead of its official enactment in 1929. The constitution defines the fundamental law of the country and the powers of the institutions. It can be amended via either a supermajority in both houses of the National Assembly or via a constitutional referendum.

Government

The Mardin Isles has a semi-presidential system with a unicameral legislature. The National Assembly meets in the National Assembly Building in An Ráṫ and is directly elected every four years.

The position of President has little vested powers, with the role intending to serve as more of a ceremonial figurehead for the state. However, the President does have the power to temporarily veto any bill presented before them, with it being referred back to the Senate and then, once again to the President who is then obligated to sign the bill. All bills must be passed by both chambers of the National Assembly and signed off by the President before becoming law.

The Prime Minister (Mardic: taoiseach) is the head of government and is elected by the Chamber of Deputies. The Prime Minister must be a member of the Chamber and is generally the leader of the largest party in government. The Prime Minister appoints members to the Council of State with approval of the National Assembly. The Council of State is also colloquially referred to as the cabinet.

There are 115 seats in the National Assembly. Elections for the Assembly use open-list proportional representation in each of the counties of the Mardin Isles. Each district returns between two and fourteen deputies. Elections for the National Assembly take place every four years, while presidential elections take place every six years.

For most of the Mardin Isles' independent history, the Mardic League have been the dominant political force. The League has finished first in 25 of 28 elections since 1926, and has occasionally enjoyed an overall majority. The League are broadly centre-right and have been dubbed as a catch-all and even a populist party. The Labour Party are the main opposition and are broadly centre-left. The Labour Party has for most of the last century been seen as the second party of Mardic politics, but have been first place in the three elections in which the League were relegated to second place. The Civic Party and the Social Democratic Party are the third and fourth largest parties respectively and have recently been seen as kingmaker parties, either providing for a League government or a Labour coalition. The Left Greens are the fifth largest bloc and were formed from the former Green Party and Left Alliance in 2001, while the Country Alliance is a conservative, rural-based party and have traditionally supported League governments.

Administrative divisions

The Mardin Isles is comprised of twelve counties (Mardic: tuatha), which are further divided into municipalities. Counties are governed by county councils (Mardic: comhairle tuath), which are responsible for local government, public healthcare services, policing and wider public transport. Municipalities, the second-level subdivision, were introduced in 1989 and replaced the standard town and city councils. Municipalities are responsible for schools, planning, emergency services, local transport and other local services including amenities, youth facilities and cultural events. In addition, four municipalities have special status as city municipalities. These city municipalities have increased autonomy, and have a strong-mayor form of government with a directly elected mayor. As with national elections, all local elections use proportional representation.

|