National Functionalism

Template:KylarisRecognitionArticle

National Functionalism | |

|---|---|

| File:NationalFunctionalistAxe.png | |

| Ideology | Cultural nationalism Corporatism Militarism Syncretism Reactionary modernism Totalitarianism Chauvinism |

| Political position | Far-right |

| Part of a series on |

| National Functionalism |

|---|

| File:NationalFunctionalistAxe.png |

National Functionalism (Gaullican: Fonctionnalisme national) is a far-right, authoritarian, cultural nationalist political ideology.[1][2] It is loosely based on the sociological theory of functionalism,[3] characertised by beliefs in a strong centralised state, a rejection of individualism, a belief in superiority based on culture and cultural origins, and the concept of the state as a living organism of which individuals are constituent parts, commonly referred to as the communauté populaire.[2] The term neo-Functionalist emerged following the Great War to describe groups emulating the Functionalist ideology.[4]

National Functionalism arose in Gaullican militaristic political circles in the late 19th century, following the War of the Triple Alliance. Gaullican defeat in the war, the loss of traditional territories such as Kesselbourg and Hennehouwe and the fragmentation of traditional allies in Soravia and Valduvia left the nation diplomatically isolated and fueled revanchist sentiment.[5]

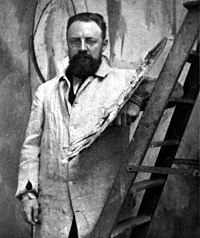

The tenets of the ideology can be traced to Gaëtan de Trintignant, a Gaullican Field Marshal who wrote numerous political treatises demanding a rejection of the modernity typified by the constitutional amendments that had whittled the power of the Gaullican monarchy following the Age of Revolutions.[6] In two political works, de Trintignant outlined his beliefs on the necessity of a strong central authority, a rejection of both laissez-faire capitalism and international socialism, a strong sense of social cohesion underpinned by a civic national identity and the establishment of the means to spread this identity.[1][7] Inspired by the growing field of sociology, de Trintignant viewed the state as a parallel to the human body, with a healthly state achieved when each part was working in concert.[8]

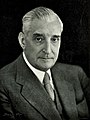

Functionalism is considered to have truly entered Gaullican politics in 1909, when Rafael Duclerque founded the Parti Populaire (PP).[9] In the tumultuous politics of the 1910s following the Great Collapse, the party grew rapidly.[10][11] This was in part due to the support of its paramilitary wings, the Chevaliers de l'Empereur and the Veuves de Sainte Chloé.[12] It became the largest party on the political right in the election of 1916 and after the bitterly-contested 1919 election came to power by forming an anti-communist coalition.[13][14][15] Duclerque consolidated his rule by outlawing opposition parties through the Comité de salut public and eventually replaced the constitutionalist Aurélien with the Functionalist Constantin III.[16][17][18] In the 1920 election, the PP was elected unopposed, having established a one-party state which would last until the end of the Great War.[19]

There is some debate regarding whether National Functionalism is an ideology specific to Gaullican political development, or if it has had wider influence.[20][21][22] It has been argued that Shangean National Principlism was inspired by National Functionalism and in Euclea itself Functionalism and ideologies adjacent to it emerged in a number of primary southern Euclean countries such as Etruria (National Solarianism), Paretia (Palmeirism), Piraea (National Alignment) and Amathia (Amurgism), as well as in the northern Euclean nation of Ruttland (National Resurrection), in part due to the influence of pro-Gaullican elements of national militaries.[23][24][25][26]

In the modern day, National Functionalism has experienced a sharp decline. The ideology was officially outlawed in Gaullica as a threat to constitutional order following the Great War and its proponents were targeted by DENAT as part of the defunctionalisation of the country.[27][28] Modern neo-Functionalists are a fringe movement in Euclean politics.[29] Nevertheless, in the context of nationalist groups like the Etrurian Tribune Movement and Paretian O Povo, Functionalist has re-entered political discourse as a pejorative term for members of those parties.[30]

Etymology

The Gaullican term fonctionnalisme is a reference to the sociological term, derived from the works of René Dajuat and his student Hugues Subercaseaux, which itself stems from the medieval Solarian word functionalis.[3] Gaëtan de Trintignant aimed to present a political theory based in empirical science which was wholly independent from Revolutionary Rationalism. During his post-war years as a writer and fringe political figure, he became increasingly enamored with the developing field of sociology then in vogue within Gaullican academia.[6][8] In a public letter, he wrote, "if we were to understand society, we would understand everything! By understanding social structure, we can create a society that is, of course, greater than all others."[7]

His desire to formulate a political theory on the basis of this idea of "purpose" or "function" led him to write his manifesto, The Function of Man, in 1881. In it, he repeatedly calls for a form of functionalism to identify which parts of Gaullican society had, in his view, enabled it to become the pre-eminent world power, before asserting the moral obligation to spread Gaullican civilization to the world.[1]

The term fonctionnalisme national was coined by Gaullican sociologist Max Cuvillier to distinguish the political philosophy from its sociological counterpart, though structural functionalism has increasingly been referred to simply as "structuralism".[31] From the early 1900s, and especially after the 1910 election when Functionalism first appeared in the Imperial Senate, left-wing opposition referred to its practitioners as fon-fou, a portmanteau of fonctionnalisme du fou ("Fool's Functionalism").[5]

History

War of the Triple Alliance

The War of the Triple Alliance was an enormous conflict which saw over half a million military casualites in the space of three and a half years.[32] The catastrophic defeats suffered by the war turned Valduvia into the so-called Sick Man of Euclea and plunged Soravia into civil war.[33][34] Gaullica did not suffer a defeat as disastrous as these, but nevertheless the defeat left a lasting impact on the public and in the political consciousness. The loss of both traditional allies upended longstanding Gaullican foreign policy, and Soravia's change in government in particular culminated in an anti-Gaullican feeling in Samistopol.[35][36]

The main lasting legacy of the war in Gaullica was the independence of Hennehouwe and Kesselbourg under the Congress of Torrazza. The two countries were, in the view of the Gaullican intelligentsia, artificial constructs created to be buffer states by Estmere. The region thus came to be known as les frontières (literally: "the borders") to Gaullican nationalists. The loss of these territories and other grievances related to the war fueled a feeling of resentment against Estmere and Werania in Gaullican politics.[37] Throughout the next decade, many in the Imperial Senate clamoured for the continuation or resumption of war with the two powers.[36] Barthélémy Vidmantas, a member of the Senate and future Premier, outwardly called for a resumption of war with Werania over grievances relating to the Ruttish Question.[26]

Gaëtan de Trintignant was one of the most successful Gaullican commanders during the conflict, having successfully routed an enemy force which had laid siege to Matīspils in allied Valduvia.[8] This was followed by the Arvorne Offensive, in which de Trintignat orchestrated an attempt to inflict a major defeat onto Estmere that would force it to sue for a separate peace. The offensive saw initial successes, but began to stall as Soravian and Valduvian leaders called for peace and rising deaths led to the conflict growing increasingly unpopular at home.[32] This led to the idea first outlined by de Trintignant that the army could have won the war had it not been for Verlois stabbing them in the back. The feelings were popular attitudes among the military establishment and high command, who felt that the empire had been denied the chance to enter negotiations with some level of parity with the victorious powers.[38]

The stab in the back myth was fundamentally an anti-democratic, collectivist and authoritarian one. It was bourne by the belief that a democratic government of bureaucrats and legislators in Verlois beholden to individualistic interests had ruled over the "collective will" of the Gaullican people, in a betrayal of the war dead.[2] This anti-democratic feeling would form the basis of National Functionalism as it began to develop.[5]

The Function of Man

Gaëtan de Trintignant wrote Functionalism's seminal text, The Function of Man, in 1881.[1] The book is foundational to the ideology.[5] The Parti Populaire nominally venerated the book, although many of the book's more radical prescriptions were ignored as the party leadership found it necessary and, at times, preferable to work within the existing system.[39] Rafael Duclerque had a personal copy of the text which he read in times of uncertainty, and after his consolidation of power he made it required reading throughout students' academic careers.[40][16]

In the text, de Trintignant outlined the basic principles of Functionalism.[1] These principles were written as the culmination of years of political experimentation where the Marshal had attempted to consolidate his critical views of individualism and "perverse collectivism" with his concerns of moral and social decadence stemming from a common cause of the Weranian Revolution.[6] The Function of Man was written as an attempt to scientifically curate a political ideology on the basis of sociology distanced from rationalism. In this regard, it was nominally supported by sociological observations on communal and collective identity, economic prospects, human attitudes towards "social abnormalities" and what de Trintignant called "absolute order" and the need for "someone to tell you what to do".[1][2]

The majority of the book was written by de Trintignant between the years of 1870 and 1875, though it underwent numerous edits until it was published six years later.[6] To give credence to his book, Trintignant consulted many of practioners of the new social sciences, such as René Dajuat and Hugues Subercaseaux.[6][3] While both eagerly provided him with sociological theory and observations, neither endorsed the book.[41]

The book was finally published in 1881.[1] At the time, de Trintignant viewed the work as a failure as no political body within Gaullica had taken interest in it.[6][8] He also viewed the events of Sougoulie as a disappointing "rejection" of civilisation and wrote that he was unsure if he had overestimated the "capacity for civilisation" amongst Gaullica's colonial subjects. De Trintignant felt that his "political revolution" had failed as he wrote in his memoirs, Reflections On and Of War.[42] The final years of his life saw the foundation of the Socialist Workers' Party, the first Nemtsovite party in Gaullica and the herald of a rising social movement.[43]

Âge des Gens Heureux

The period which followed the end of the War of the Triple Alliance and preceded the Great Collapse has become retrospectively known in Gaullica as the Âge des Gens Heureux ("The Age of Happy People"), corresponding to the Estmerish Long Peace and the Weranian Prachtvolle Epoche.[44] It was marked by cultural, scientific and technological advancement, a general rise in living conditions and the expansion of Gaullican influence across Coius through colonisation.[45] The initial sense of betrayal from the conclusion of the war eventually retreated. Gaullica had lost to the increasingly prestigious Alte Bruderschaft, but it remained a prominent Great Power.[36][10]

This sense of cautious optimism eventually gave way to an acceptance of peace and prosperity among the upper classes, in part due to advancements in technology and standards of living. Verlois maintained its position as the leading city of culture, economics and science globally, while other cities in the empire such as Adunis, Montecara and Rayenne also grew in size and influence.[44] The rise in standards of living was not distributed evenly, however, which led to social conflict. The working class and colonised peoples remained subject to widespread deprivation, while military figures continued to criticise the civilian government for having failed the nation in the war.[11] These both provoked political radicalism, giving rise to socialist, republican and anti-clerical movements such as the Socialist Workers' Party (a predecessor to the SGIO) and to revanchist sentiment in an increasingly war-hungry general staff and officer corps which became partial to National Functionalism.[43][46] Radicalism never took hold of Gaullican government directly, but the spectre of it prompted moderate governments to institute gradually more expansive social security to combat social ills.[47][5] The rise of political radicalism also caused the growing middle class to express concern about the possibility of a socialist coup, and develop increasingly anti-communist opinions.[48]

The expansion of the Gaullican colonial empire throughout the period was also relevant to the development of Functionalism. Territories in Bahia and Rahelia were consolidated, existing possessions such as Montecara and Atudea were integrated further and government oversight was brought to Dezevau as the private Saint Bermude's Company was transformed into the Bureau for Southeast Coius.[49] These developments influenced the cultural nationalist outlook of the ideology.[2] Gaullican relations with Imperial Shangea also improved in this period, as treaties were renegotated and Gaullica supported the country's war against Etruria. The Shangean victory in this conflict shocked much of Euclea, and created the myth among Functionalists that Shangea was the "imperial twin" to Gaullica, leading to the eventual alliance between the two.[36][23]

New cultural movements also arose during this period, many of which influenced and were influenced by Functionalism or proto-Functionalism. The most prominent among them were the Futurists, who were devoted to the rapid pace of modernity. In their view, modernity itself and its hallmarks such as machinery, speed, automation and invention were expressions of art. They developed this new school of thought in all of the arts, from architecture to theatre. The Functionalist idea of the Nostalgic Future drew many Futurists toward the ideology, and many quickly became enamoured by it, emerging as some of the movements' strongest supporters.[50]

The end of this period saw the emergence of the first party entirely dedicated to National Functionalism, when in 1909 the famous Verloian dentist Rafael Duclerque founded the Parti Populaire.[9] This was the end of his political journey from disillusion with social democracy to Functionalism.[40] The party aimed to capitalise on the rising resentment felt by the lower and middle classes, though the focus would eventually shift more prominently to the middle class, playing on their fear of a radical, socialist revolution.[48]

Great Collapse and rise to relevance

The Great Collapse in 1913 had an adverse impact the Gaullican economy and on Gaullican society. The economic shock led to widespread unemployment as companies defaulted on loans, followed by a sharp rise in the cost of living as inflation led to goods becoming prohibitively expensive.[10] These pressures fueled political polarisation, violence and growing extremism, which helped the SGIO and Parti Populaire emerge from the fringe as major parties.[11]

The crisis devastated the political establishment, and the country experienced extensive political instability between 1915 and 1919 as a result.[47] The conservative and monarchist Party of Order formed the government when the crisis began, and their response led to their defeat in the 1916 elections. They were replaced by the liberal Radical Action, and lost their position as the largest party of the political right to the Pari Populaire.[13] The new Radical government nevertheless also struggled to combat the crisis. Due to the system of proportional representation used at the time, the Radical government of Ernest Jacquinot was reliant on a coalition government with the Confessional Catholic Party and a litany of minor parties. They struggled to pass legislation due to historically poor relations between the PCC and the traditionally anti-clerical Radicals.[51][52]

A major reason for the continuing effects of the Collapse was the policy of both major parties toward the gold standard. The PO and the Radicals were both fixated on maintaining the gold standard, which greatly overvalued the Gaullican denier and exacerbated the crisis.[53] The Radicals were only convinced to abandon the gold standard following the special election in 1918, in which they lost a significant percentage of their votes and were forced to enter a confidence and supply agreement with the SGIO. The end of convertibility and the abolition of the gold standard was the only meaningful achievement of this uneasy coupling, but it remained broadly unpopular in the country at large. The devaluation worsened inflation which was criticised by Rafael Duclerque for "weakening the enamel of fiscal stability", and the government subsequently collapsed in mid-1919.[13][53]

The 1919 election was a watershed moment in Gaullican politics, as it saw the culmination of the radicalisation of Gaullican politics.[14][19] The SGIO emerged as the largest party, with over a third of the vote, while the Parti Populaire was the second largest, with just under a third. The traditional parties of the left and right were both devastated.[14][13][54] SGIO leader Guillaume Rodier and PP leader Rafael Duclerque were widely seen as the only viable candidates for Premier.[55] The SGIO aimed to consolidate the left parties into a minority government with support from the Radicals and the PCC, while Duclerque aimed to unite the right into an anti-communist coalition.[15][19] Emperor Aurélien made it clear that he would appoint whichever candidate secured the support of the Senate, "whether or not they agreed with [his] existence".[18] The fear of a communist government reliant on separatists such as the MSMR spurred the centrist and right-wing parties into supporting Duclerque; most notably, Radical leader Jacquinot rejected an offer to work with the SGIO, and instead agreed to work with Duclerque.[52][15][19] Duclerque would be appointed Premier in November 1919 on the back of this coalition.[56]

A major factor in the politics of this time was political violence. It grew from a relatively rare occurrence into a widespread phenomenon.[12] Political violence between paramilitaries associated with the Parti Populaire (the Chevaliers de l'Empereur and the Veuves de Sainte Chloé) and those associated with the SGIO (the Garde Rouge) became such a fact of political life that they became regularly satirised by domestic media such as the Héraut de Verlois, as well as foreign media such as The Pillory.[57][58] Street brawls, firefights, murders and sabotage escalated until the Functionalist consolidation.[12]

Consolidation of power

The new Parti Populaire-led coalition officially contained the Catholic Confessionalists and Radicals, but it also relied on the tacit support of the Party of Order and the minor parties of the miscellaneous right.[19] Duclerque had witnessed the collapse of earlier coalitions and so his government immediately concerned itself with tackling the pressing issue of the SGIO. He established the Comité de salut public to secure the "safety of the nation", granting it the power to assess domestic threats. In theory it was a non-partisan institution, but in reality it was stacked with former paramilitary members loyal to Duclerque. These paramilitaries had, for the time being, been disestablished to appease his coalition partners. The Committee concluded in January 1920 that the SGIO and its sister parties were "fundamentally anti-Gaullican" and a threat to "the Gaullican way of life".[16]

The following day a special session of the Senate was held to debate the Safety of the Nation Act, which would criminalise the SGIO and other socialist organisations, expelling their members from the Sente and reallocating their seats to the remaining parties; giving the Parti Populaire an absolute majority.[15][16] The act passed with only token disapproval from the left-Radicals and a small number of PCC deputies.[59] The SGIO nevertheless arrived to their final session of the Senate to unanimously reject the bill. Rodier used his last speech in the chamber to repudiate Functionalism, although he was met with contempt and chastisement Functionalist deputies, who heckled him throughout.[60]

You may have the day, but we have the century. History is on our side. Today we may end up in a ditch, but tomorrow we will be your grave-diggers.[60]

The bill met more resistance outside the Senate. Trade union leaders aligned to the SGIO called a general strike across metropolitan Gaullica to protest the Safety of the Nation Act. The government initially tried to drive a wedge between the unions and SGIO leaders, but eventually moved to instead violently suppress the strikes.[61] The officially disbanded paramilitaries carried out assassinations of SGIO leaders, while the government arrested union leaders and other SGIO figures.[12][16] The government also brought in the non-socialist Catholic trade unions to act as strikebreakers, mitigating their effects. The strikes were effectively over by April 1920.[61]

Emperor Aurélien was a major obstacle to Functionalist rule, as he was a constitutionalist and opposed attempts to consolidate power at the expense of the democratic system.[18] As Gaullica was a semi-constitutional monarchy, he had a number of powers which he used to stall and block Functionalist legislation.[47][16] He refused to dissolve the Senate, as he feared that an election without the SGIO would return an outright Functionalist majority.[19]

Aurélien's actions caused a rift in the royal household, as his son Constantin the Prince Imperial was sympathetic to the Functionalist philosophy.[17] Duclerque planned to force legislation through the Senate to force Aurélien to abdicate, but Constantin and forces in the royal household loyal to him acted first.[16] The palace's press office, entrance, checkpoints and armoury were seized by palace guards and Verlois police loyal to the Prince Imperial in the early hours of 29 March.[62] Aurélien was awoken and informed by his son that his reign was over. Aurélien initially resisted, but was eventually forced at gunpoint to issue his abdication.[17] He later claimed that he believed a civil war would break out if he did not.[18] The palace then released a press briefing which announced the abdication on the grounds of ill health, and proclaimed Constantin the new Emperor.[16] Aurélien, his wife and loyal staff would then enter self-imposed exile to Cassier through Caldia.[18]

Constantin then used his power as Emperor to dissolve the Senate and call fresh elections in November 1920. He praised the actions of the Committee and the new government, calling for the restoration of order.[17] Duclerque supported the new election, arguing it was a chance for a public plebiscite on entrenching the powers of the Senate by lengthening its term while also centralising power in the office of Premier to oppose "incessant bureaucracy".[19] The election was not free and fair. The Parti Populaire used the state apparatus to campaign on its behalf.[16] Military units and former paramilitary members guarded voting booths, intimidated opposition candidates into stepping down and engaged in voter intimidation.[12] The official results saw the Parti Populaire win almost every vote.[19]

This complete control of the state allowed the Functionalists to pass almost all key components of their ideology in the first half of the decade.[16] Duclerque mandated the dismantling of the existing unions and mandated membership of the new Fédération du travail, expanded social programmes for Gaullican citizens, neutered the power of the Senate and consolidated power in the position of Premier, increased the benefits of military service, embarked on a series of extensive public works programmes to combat the lingering effects of the Great Collapse, created the Ministry of Popular Culture and invested in military and civilian research and development.[5][9] The new Ministry of Popular Culture, with the support of Constantin, funded experimental new architecture, art, film, music and theatre under the influence of the Futrist movement, which became widely cultivated, taught and promoted. Art which did not conform to the Ministry's wishes were censored and suppressed.[50] The Functionalists also continued to eliminate oppositon with impunity, best exemplified by the assassination of Gustave Fournier, one of the few Radicals to denounce his party's involvement with the Functionalists. He had previously chastised them for "praising the aim of [their] own firing squad" on the floor of the Senate.[19][63] He became a symbol of anti-Functionalist resistance, which made him a target for Functionalist street thugs, who abducted and murdered him on 3 August 1920.[16] The domestic reaction was muted, despite the widespread outrage abroad, showcasing the unassailability of the regime.[63][64][65]

The Parti Populaire also solidified Gaullican foreign policy in this time.[36] The most notable example of this was the signing of an alliance with the Shangean Empire, which would go on to form the basis of the Entente.[23] The government would also support like-minded figures in neighbouring Euclean countries.[25] In Amathia, they provided financial and military support to the rising Amurgist faction, shared intelligence which proved pivotal in their coup and were among the first to recognise the new Amathian government. In Paretia, they supported the political movement of Carlos Palmeira and provided intelligence and military support to his government. Eventually, the Emperor and high-ranking functionaries were invited to Precea as honoured guests of Roberta II. Support was also provided to Functionalists in Piraea.[66]

Functionalist foreign policy at this time resumed revanchist rhetoric surrounding les frontières.[37] Gaullican claims were pushed in September 1926, when the military invaded Kesselbourg in defence of Gaullican minorities.[66] The invasion was concluded by 17 September and the next day Duclerque declared from Kesselbourg City that this was the first of "many wrongs" to be righted.[19][67] The annexation was met with strong condemnation from Estmere, but the other members of the Tripartite Agreement were muted in their response.[68] This emboldened the Functionalist regime in pressing historic claims on Hennehouwe. In December 1926, Gaullican forces overran Hennish defences and established effective control over Petois-speaking areas.[67] They did not pursue Hennish forces into north of this. Foreign minister Pierre-Antoine Baudet assured the Tripartite Agreement that "no more" of Hennehouwe was to be conquered. The Functionalists set up local government in the conquered regions which were officially distinct from the central government, allowing them to claim that they were not in violation of the Congress of Torrazza.[68]

Great War

The Tripartite Agreement hoped that Gaullican expansionism would end with the reclamation of les frontières, but they were mistaken.[67][68] Duclerque's inner circle saw war not just as inevitable, but as preferabe. They adhered to the realist view that war was natural and that power was the most important part of international politics.[2][69] They also wished to unleash the potent military which had been advanced and reformed through the early half of the decade.[5] Not long after his Kesselbourg address, Duclerque infamously declared to his inner circle that "war [is] on the horizon" and that "all of Euclea will be at war within a year".[40] The Second Sakata Incident occurred less than a month later. Negotiations quickly stalled. Shangea and Gaullica declared war, Senria invoked its alliance with Estmere, and Estmere triggered the Tripartite Agreement.[68]

The Gaullican regime had mobilised the rest of the military while negotations stalled, having never demobilised the forces involved in the Hennehouwe Crisis. The Gaullican military swiftly head to fronts across Euclea. The early years of the war saw trench warfare and scattered victories, but a breakthrough saw the collapse of Estmerish lines and the Fall of Estmere.[70][71] Gaullica would occupy most of mainland Estmere until liberation, setting up collaboration governments.[25] The regime engaged in a campaign of repression against Estmerish and Hennish resistance, executing partisans and sending prisoners of war to work camps,[72] while also enacting Functionalist policy in the occupied territories: the Centre for Sexual Research in Morwall was repurposed into a electroconvulsive therapy clinic, for example.[73][74]

In the west, the fighting was some of the harshest. Gaullica and Soravia traded vast swathes of territory in huge offensives with massive loss of human life.[70] Gaullican Functionalists aligned with anti-Soravian partisans and independence movements, even when these groups were not directly aligned to Gaullica.[75] This did not prevent Functionalists from conscripting civilians and prisoners of war of any ethnic group into forced labour or penal battalions. The Functionalist regime operated around 800 prisoner of war and work camps, with over three million prisoners housed at the peak of the war.[76]

The Functionalists became more pragmatic when the regime entered total war. Society was mobilised entirely for the war effort, with some ideological principles discarded for economic pragmatism and civilian industry almost entirely repurposed for war.[39] Pre-war domestic programmes were abandoned or scaled down where they were not immediately neccessary for war. This impacted the popularity of Functionalism in Gaullica, though this was offset by the patriotic fervour of the war.[48] Nevertheless, as Gaullica's position in the war declined from 1931 onwards, domestic resistance to Functionalism was great enough for a Gaullican resistance to begin to re-emerge with Grand Alliance assitance.[77][33] This resistance would begin to sabotage industrial output.[78]

The closing years of the war saw the regime begin to collapse under its weight. Fellow travellers in the Gaullican military began pushing for a surrender to Werania, fearing the complete destruction of the nation otherwise.[79] Duclerque himself became increasingly melancholic after the liberation of Estmere in 1932.[40][77] Allied troops breached the Zilverzee line less than a year later, and when Gaullican forces retreated south to the Sylvagne line, there were fears of general mutiny.[70][78] The breaching of the Sylvagne line in March 1934 was followed by the suicide of Emperor Constantin, and morale collapsed.[17] Duclerque called for unconditional surrender in May.[70]

The war continued as Shangea fought on and pockets of Gaullican military refused to surrender, but in most of Euclea it was over.[70] The Grand Alliance moved to dismantle Functionalism and the institutions which had enabled it, beginning a long process of defunctionalisation, deradicalisation and demilitarisation through the establishment of DENAT.[28] Gaullica was occupied by a joint force comprised of administrators and military units from across the Alliance, along with limited numbers of anti-Functionalist Gaullicans.[80][78] A new republican constitution was implemented in 1940.[81] Members of the regime were also put on trial for crimes against humanity at the infamous Rayenne Trials. The Alliance convicted a number of Functionalist functionaries and officers, but the biggest trial was of Rafael Duclerque, who was convicted on a number of war crimes and hanged.[82][40]

Post-Great War

Gaullica

Functionalism, having lost the Great War, was almost immediately discredited as a system of government.[5] The Grand Alliance went to extraordinary measures to deradicalise Gaullica's military and civilian population.[81] Segments of the country were carved away as almost autonomous statelets, large swathes of continental and colonial territory was granted independence or transferred in ownership, the Gaullican empire was dismantled, stringent restrictions controlled the size of the military and Gaullica's existing democratic institutions were empowered as per allied directives.[80] Competing influence between Soravian authoritarianism, Estmerish and Weranian democracy and Valduvian socialism morphed Gaullica's constitution into a "model", whereby it was explicitly equipped with means and measures to ensure a strong democratic state.[81] Even the election of a former Emperor, Aurélien, to the seat of the Presidency did not see a return to older systems of government.[80]

Within Gaullica, Functionalist sympathisers were ostracised.[83] Many important Functionalists were tried and imprisoned, or in some cases killed. The most famed measure came from the establishment of the Département national pour la transition démocratique (National Department for the Transition to Democracy), a secret police that initially reported to the Weranian Strategic Intelligence Service and Weranian Ministry of Defence.[28] DENAT was concerned with political extremism from both the left and right wings of the political spectrum and fought these ideologies through espionage, infiltration and - in extreme cases - assassination.[28]

Functionalist parties were outlawed under Article 12 of the constitution, with the view that they were threats to the integrity of Gaullican democracy.[27]

In spite of the measures instituted to see the ideology stripped of supporters, there were many in the immediate post-war period who felt embittered.[84] The popularity of the Final Soldiers, Gaullican military servicemen and generals who refused to surrender and continued to fight well past the end of the Great War, was unquestionable in domestic Gaullica.[85]

Due to the concern of Functionalist resurgence of reintegration, right-wing parties and those that had aligned themselves to the Functionalists were treated with immense suspsicion by the political establishment of the Catholic Labour Union. The CLU presented itself as the vanguard of Gaullican democracy, working to implement a new stage in the history of the nation, and aggressively dominated politics for the first thirty years of the republic's existence.[86]

Federal education systems focused increasingly on the teaching of not only politics but on civil engagement and duty. The CLU passed laws penalising failure to participate in the democratic process, eventually making voting compulsory, on a platform known as démocratie non négociable (Non-negotiable democracy).[86]

Etruria

Following the end of the Great War, sentiment in Etruria was surmised with general apathy and confusion. The popular newspaper Voce Popolare (People's Voice) ran a headline following the negotiations that led to the signing of the Treaty of s'Holle that read "Abbiamo vinto?" ("We won?") in reference to the nation's failings at the diplomatic table to secure almost any of its war objectives.[87] The "great betrayal" and "national embarrassment" of hundreds of thousands of Etrurian dead for, as Ettore Caviglia put it: "a piece of paper", embittered both the left and right to the democratic government of Etruria.[88]

Etruria's military hierarchy had entered the war against an enemy many of them personally favoured.[89] Sentiment amongst the officers of Etruria was generally negative, viewing the Great War as a rejection of the military camaraderie between Gaullica and Etruria's general staff. Many of these openly pro-Gaullican military men were softly-exiled during the war by the civilian government to the colonies.[89] Their return at the end of the war heralded a resurgence in right-wing sentiment, that was fuelled by the growing unpopularity of Marco Antonio Ercolani's government. By 1936, two years after the war had ended, Ettore Caviglia and his ally Aldo Aurelio Tassinari had formalised a political ideology of functionalism catered for Etruria: National Solarianism. Their aims were largely imperialistic and revanchist, seeking to correct "wrongs" inflicted on Etruria by their very allies some years prior.[24]

Functionalism spread into Etruria's government through the establishment of an emergency government that was formed in response of growing left-wing agitation, strike action and fears of revolution.[90] This military government eventually practiced a coup d'etat on the elements of the emergency government not controlled by them, in what became known as the Legionary Reaction of 1937. Caviglia and Tassinari declared themselves Co-Leaders of a Solarian Republic of Etruria and began to implement their Solarianist policies.[91]

National Solarian Etruria, widely criticised as a resurgent Functionalist regime in Southern Euclea, would drag much of the world to war in 1943 following its declaration of war on Piraea, subsequent attacks on Euclean mandates in Coius it viewed as its own, and an invasion of Paretia. The Solarian War quickly brought in the Community of Nations, who led the response to Etrurian aggression, and by 1946 had defeated Etruria. From 1946 - 1948, Etruria was governed under a Community of Nations mandate that sought to deradicalise the nation; using many of the same techniques employed in Gaullica a decade prior.[92]

As put by Wilhelm Hahn in his book The Functionalist Mark on Euclea, "for the second time in ten years, Functionalism had been destroyed by democracy - but many of the mistakes of the first time remained". Etruria's Third Republic was established in 1948, though many of the conditions that exacerbated the rise of Functionalism in the country, like ethnic tensions and poverty, persisted.[93]

Satucin

The end of the Great War saw conditions placed on Satucin, with several Grand-Alliance aligned political parties either being formed or refounded in the years following the surrender of the Gaullican dominion.[94] The Republican Movement was the most politically dominant force from the years of 1935 - 1940. Premier Marquette was faced with the task of implementing the Grand Alliance drafted constitution, which outlined complete independence and separation from Gaullica, sought to outlaw National Functionalist political parties, and brought about universal suffrage to both male and female voters over the age of 18. In order to maintain power in the legislature, the Republican Movement was aligned to various left-wing groups, including the newly formed socialist Workers Party.[95]

However, growing economic troubles fuelled by an extreme expenditure of resources during the Great War, a loss to existing imperial markets for Satucine exports, and the turbulence of existing right-wing agitation across the Satucine states handicapped the effectiveness of the Republican Movement.[94] Historian Rébecca Voclain described the Republican Movement as "having the unfortunate situation of fighting every single unpopular issue at once; from rejecting a monarchy, fighting rising inflation and unemployment, and dealing with perceived enemies of the nation".[96]

Following the deployment of the military to Bonhavre in an attempt to break up remnants of right-wing insurgents in the province, Marquette's popularity took a sharp nose dive as the Republican Movement was seen as 'eager to fight Satucines'. Marquette faced increasing calls to resign, from an increasingly popular and bold Henri Masson. Masson and his rebranded Parti d'action saw a surge in popularity as he publicly vowed to "tear down the foreign constitution" and "fix the economic crises".[97] He portrayed himself as a reformed democrat, a champion of the ideals of the system of democracy and played up the fears of a red scare within Satucin. In the legislative election of 1940, Masson saw himself return to government for the first time since the Great War, and he immediately set about trying to reverse the actions of the Republican Movement.[25]

Internationally regarded at the time as being the beginnings of a "resurgence of Functionalism in Asteria Inferior", it was soon relegated to the far more dismissive "last gasp of a dying ideology", as although Masson was able to secure several of his policies, his attempts to consolidate the position of President and Premier into a single authority ended up destroying his popularity as Satucine media and opposition drew stark parallels to the situation before the war. The legislative election of 1944 saw the PA be thoroughly bested by the newly formed Independent Democratic Party.[96]

Piraea

The Kingdom of Piraea had fought alongside Gaullica during the Great War, and in the immediate aftermath found itself occupied by Grand Alliance soldiers. The onus of occupation fell to the Etrurian Republic.[98] They oversaw the implementation of a new constitution under Stephanos Vitapoulos, who had led a democratic Piraean government in exile in Etruria. Despite Vitapoulos' popularity as an anti-functionalist liberal, the first elections of the Piraean Republic saw Themistoklis Ioannopoulos of the PSEE come to power. His government immediately began to rectify the mistakes that had led to a Functionalist rising in the state. Ioannopoulos' government granted women suffrage, expanded agricultural reforms and continued secularisation policies by nationalising hospitals and cemeteries ran by the church.[99]

From July to November of 1943, Etruria waged a war of total occupation against the First Piraean Republic, which forced Piraea's surrender in November of 1943. Both left and right wing insurgents roamed the countryside from secluded bases in the Piraean coast and rugged interior and under General Konstantinos Athanopoulos, Piraean resistance was organised beyond party affiliation in what became known as the Prostasía. This 'alliance of black and red' would ultimately help liberate Piraea as Community of Nations forces brought the fight to Etruria by 1946.[100][101]

Athanapoulos utilised his popularity as the most senior member of the Piraean military to fight beyond surrender to launch a political career and was viewed as the only legitimate representative of government.[100] In the 1948 elections, his National Alignment became the largest in the senate.[13] In spite of the Functionalist aligned doctrine of the National Alignment, Athanapoulos ignored several PSEE reforms in favour of aiming to instil conservative values in the newly nationalised education sector. Echoing early Gaullican functionalsit propaganda, the NA claimed to be "fighting a war on degeneracy". With the support of several right-wing parties and even nationalist dissent from left-wing parties, Athanapoulos was able to consolidate the Piraean state around himself - and declared the Second Piraean Republic several months into his term, largely on drummed up fears of a red scare and by drawing on emotive, angry responses to the horrors of the Piraean genocide.[25]

Functionalism would continue to dominate the Piraean political scene for over thirty years, with an heritage that bears immense controversy until today. In spite of these aspects of state terror, killings, disappearances and immense authoritarianism, Athanapoulos' remained personally popular. His government ushered in countless infrastructure projects, improved literacy rates and aimed to solidify the nation against further Etrurian threat. However, a second invasion of the Etrurian Third Republic in the region of Tarpeia, discredited the regime and opened voices of against the junta; the military government was forced to adopt significant modifications, which were enclosed in a pragmatic economic liberalism led by technocrats[2]

However, the Etrurian annexation of Tarpeia and Athanapoulos' death accelerated the Piraean rejection of Functionalism, and by 1979 the junta he ran was toppling from within. In 1980, the remnants of the junta were forced to open elections, where it was electorally annihilated.[13]

Amathia

The initial collapse of the Amurgist regime in Amathia was followed by a strong popular feeling of retribution, which was materialized in many partisan activities and summary executions directed at the leaders and members of the movement, including the execution of former leader Ghenadie Isărescu in Arciluco.[102] The rapid collapse of central authority in the country and the continued resistance by some Amurgist military and paramilitary units however prevented any sort of official, nation-wide policy in regards to the former National Rebirth Movement. With the general surrender of the Royal Amathian Army, the country was roughly divided in two - with a Soravian occupation zone to the west, and the Etrurian military authorities to the east. In parallel to the occupation, two separate governments were formed in opposition to the exiled royal government - a Council Republic in the west, and a National Government in the east.[103]

The eastern occupation zone was notable for its lack of any deradicalization policies. Etruria's rising functionalist movement, and the right-wing sentiment that was prevalent in many of its military units prevented any sort of organized anti-Amurgist program on the same scale as what was happening in Gaullica, as Etrurian military commanders, once the initial phase of revenge had passed, started to collaborate with former Amurgist figures against the leftist groups that were the most hostile to the Etrurian presence.[90][104] The National Government had the support and membership of much of the former Amurgist elite, which saw in Legionary Etruria the possibility for a return to power and for victory against the councilists. Etruria's imperialist regime however only cooperated with the nationalists so as to better secure their position in the territories they administered. By late 1936, Etrurian plans to annex its occupation zone in Amathia, and the refusal of the other great powers to grant them recognition ended the legitimacy of the nationalists.[90][104]

By contrast, in the west, the councilists strongly pursued deradicalization policies.[103] The National Rebirth Movement was banned, and its higher ranking members were arrested and given to the Soravian occupation forces or tried by people's tribunals and executed. Other members and sympathizers of the movement were ostracised, banned from joining the councils or from holding important positions.[105] The removal of all traces of Amurgism was considered to be greatly important for the transformation of Amathia into a socialist society. Political forces with right-wing sympathies were not allowed to join the Republican Democratic Front - the political alliance between the Amathian Section of the Workers' International and other historical democratic parties like the National Peasants' Party and the Constitutional-Democrats.[103]

The situation radically changed with the beginning of the Solarian War however. The discrediting of the National Government, the Etrurian annexation in the east, and the Etrurian invasion served to unify the various political factions of the country in opposition to their new enemy. The failure of the Amathian Liberation Army and of the Soravian units to resist the Etrurian invasion changed the Council Republic's policies in regards to former Amurgist sympathizers, particularly in the military where high ranking officers were needed.[104] This general amnesty allowed many to escape scrutiny, and led to the general failure of the deradicalization in Amathia, as service in the war against Etruria guaranteed a reprieve from accusations. Subsequently, many former Amurgists, particularly with military affiliations, joined the Amathian Section, and played a role in the development and rise of the Equalist faction.[104]

Ardesia

Ardesia had entered the Great War as Gaullica's ally and had been one of the preeminent spots of Functionalism within the Asterias.[106] For twenty years Dinis Montecara had led the Ardesian State with an economically populist, socially conservative rhetoric that aligned itself to Functionalism. Yet with their loss at the end of the Great War, Ardesia was subject to deradicalisation efforts led by the Asterian Federative Republic and Rizealand. Much like other Functionalist powers, their post-war political development was guided by the victorious powers.[106]

Julio Avila, who had led the Ardesian government in exile in Rizealand, was elected as the first president of the Ardesian Third Republic. Avila had a hand in the creation of the new constitution for the Third Republic and he was the forefront of a regime that was dedicated to the ideals of liberal democracy.[107] Avila oversaw legislation that barred any former Functionalist statesmen from being elected or appointed to public office. Most famously he instituted the policy of Normalização (Normalisation), a mass public deconstruction campaign that destroyed monuments, art displays and symbols of the Montecara regime whilst also reverting censorship laws on non-functionalist works. Avila's largest opponent was the Ardesian military, whom he battled across all elements of the public sphere in a demilitarisation campaign.[108]

Avila resigned in 1944 and was succeeded by a series of presidents who were neither as effective or as committed to the ideals of democracy as he was.[107] Issues with the military continued and grew far more dire, especially as the nation found itself embattled against criminal syndicates and cartels in a rising pan-Asterian drug trade.[109] Neighbouring Chistovodia prompted a severe panic against socialist and communist sympathisers and agents. Political instability plagued Ardesia, especially after the ascension of Omero Povel to the presidency. His reign ended in a bloodless coup on the 13th of August, 1960.[106]

Within a year, the military who had been praised from ending the political and social crises, created the Estado Novo as political power consolidated in Dante Carmino, a former commander of the Ardesian Army.[106] Though never aligning itself to the regime of Montecara, it was ostensibly inspired by his policies and neo-Functionalist in nature. Pedrinho Dispenza, a member of the Ardesian Section of the Workers' International and lifelong critique of Carmino, described his regime as "a rebirth of the Ardesian State". Functionalism's influence within Ardesia came to an end alongside the fall of the Estado Novo, when the Ardesian Fourth Republic was proclaimed.[106]

Arbolada

During the Great War Arbolada was officially neutral in the conflict, though was economically connected to the Entente due to similarities in ideological foundation. Caudilho Maximiliano Silveira was aligned to Functionalism out of international convenience and similarity, though he maintained that his own ideological theory was distinct from the varieties found throughout the world.[25]

Following the end of the Great War, Arbolada maintained its policy of neutrality but found itself increasingly isolated in an anti-Functionalist world. In response to international pressure and threat of economic sanction and isolation, Silveira oversaw the re-implementation of elections in 1936, with the Democratic Party of Arbolada both securing a majority in the legislature and electing a "collateral president", Gabriel Nachtigall.[110]

Following this, in 1937 Silveira had his emergency powers voluntarily revoked by the House of Deputies and restored his position to its pre-1916 levels. Arbolada's functionalism suffered a quiet defeat and decline throughout the remainder of the post-war years, though it was never outlawed by the government. Remnants of Silveira's government continued to advocate for Functionalism as far into the 1960s, though their vote share consistently fell until they failed to return a deputy in 1974.[110]

Paretia

After the defeat of functionalist Paretia in the Great War, the nation would be occupied by Etruria. Grand Alliance forces helped Xulio Sousa form a government which abolished the monarchy and turned Paretia into a republic.[111] Sousa and the Paretian Democratic Party became the first President of the Republic after an election was held in 1935. The Senate of Paretia was also reformed to be more similar to that of Etruria. Functionalist elements still remained in the country, Sousa however did not want to go the way of Gaullica in repressing functionalists that remained in the country, he pleaded to allow them to run in elections, however, Etrurian authorities forced him to ban them in 1935.[112] Xulio Sousa died in early 1936, this lead to his deputy, Martinho Carreira, to take over as President.[111]

The country began to lean leftward after the death of Sousa as functionalism still existed and was allowed to exist outside of elections, many leftists wanted to further punish functionalism in the country. Carreira's government collapsed in 1936 and in the following Paretian election the left-wing Republican Workers' Alliance, which included numerous leftist and social democratic parties, took over.[13] This government was lead by Ramiro Felipes, he would harshly treat functionalists and would ban their parties from existed, as well as banned functionalist literature in libraries in the country. He would greatly decrease military power in the government, which many on the left claim was partly responsible for the rise of Palmeira. However, scandals surrounding his government and trade unions, as well as the Legionary Reaction in Etruria lead to the end of his government in 1939. General Enzo Queiroz Miranda of the Civic Patriotic Republican Pole promised to rebuild the military to defend against functionalist Etruria, as well as promised to "strongly enforce democracy in Paretia".[111]

Queiroz Miranda would combat what he perceived as threats to Paretian democracy at the time, he claimed nations like far-right Etruria and far-left Amathia were both enemies and would target both the far-left and far-right in Paretia.[111] The government would ban numerous left-wing parties in the country as well as right-wing. He would rebuild the military in order to protect against Etruria which was also rebuilding their military and pushing revanchist sentiment. When Etruria conquered Paretia in the Solarian War in 1944, some functionalists that remained in Paretia became either sympathizers and collaborationist with the occupiers or were enemies of them.[113]

Contemporary Functionalism

Almost no political party around the world actively describes itself as Functionalist.[114] Numerous political parties have been alleged to be neo-Functionalist, however.[115] In Gaullica, the Front National, a far-right nationalist party, has been criticised by political opponents of being "neo-Functionalist" and a party that is "Functional apologist". Leaders of the party, including current leader Alfred Boulanger, have caused controversy through political statements downplaying the atrocities of the Parti Populaire. Boulanger once said that "Duclerque was the greatest Premier that Gaullica has ever had", and has tweeted celebrations on important days to the regime.[115]

The Tribune Movement in Etruria has drawn strong criticism from both domestic opposition and international critics for espousing similar talking points and policies to both the National Functionalist regime and the Etrurian National Solarianism. The party's open embrace of right-wing populist rhetoric and policies, its erasing of Etrurian democratic institutions, its use of police and thugs to disrupt opposition and clamp down on protests and its reverence to the ideals of the National Solarian movement have resulted in numerous political commentators and writers branding it as the "only openly Functionalist party in the world".[30] Similarly, the party of Acima in Paretia has taken much inspiration from the Tribune Movement and has garnered similar criticism from others. Paretia's O Povo government makes it the sole far-right government in the Euclean Community, however disagreements between thr Tribunes and Acima occur over events during the Great War and Solarian War.[30]

According to Rizealander political philosopher Gabriel Rhodes "Functionalism as an ideology may have been overtly discredited, but this just meant its supporters resorted to subversion."[84] In his work The Appeal of Order, Rhodes highlights that "Functionalism exists in every society, no matter its political culture, as an apex of what it means to be conservative."[116] Controversially, Rhodes examines the tenets of major right-wing parties around the world - and draws parallels to their stances on political positions and their adaptations and interpretations of the functionalist dogma to a "modern political climate".[116]

Tenets

Functionalism is characterised as being a particularly non-traditional form of conservativism.[1][2] A highly statist ideology, Functionalism's main aims and concerns as outlined by the theories of Trintignant and their adaptations into the framework of the Parti Populaire by Rafael Duclerque were to "bring about and maintain the ideal society".[1][117] This often led to a largely pragmatic approach to economic policies depending on the situation and a fairly overall socially conservative policy focused on traditional gender roles, deference to authority and the idealisation of traditional institutions in society.[117] However, according to Olivia Édouard's assessment of the ideology, "Functionalism, at times, practiced pragmatic social policy - as was the case with women being encouraged to enter the workforce during the war."[118]

Civic nationalism

Unlike most other Euclean political entities which developed nationalism as an ethnic identity, Gaullican political theorists were often critical of that concept.[119] Traditionally, nationalism has been held to have been born by the Weranian Revolution of 1785, with Weranian radicals associating their ideas of radical republicanism with that of a unified Weranian ethnic identity.[120]

In Gaullica, by contrast, the idea of ethnic nationalism was in principle rejected.[119] Instead, some scholars have argued that a separate strain of nationalism grew there.[121] Porthos Asselineau, writing in the early 1900s, compared the "identities of the peoples of Euclea" and described of the Gaullican thought process that: "ethnic nationalism makes no sense, Gaullican identity is achievable. It is a civic identity, beyond the constraints of blood and ancestry." According to Porthos, the nationalism present within Gaullica was a "nationalism of culture; one not set in on racial or ethnic lines, but on values and a way of life that others can be educated into."[121][122][123]

In his seminal work, The Function of Man, Gaëtan de Trintignant wrote on the topic of race extensively. In the opening of his chapter: "The Peoples of Gaullica" de Trintignant states that "race is not real".[1] Functionalist doctrine and ideology on race was largely dismissive of race as a factor of identity. Trintignant surmised his belief on what it meant to be Gaullican as not being attached to the "fabrication of the Gaullican ethnic group", but a set of cultural, linguistic, moral and value-based institutions and practices. He compared it extensively to what he called "Weranic nationalism", which he argued was exclusively concerned with "linguistic brotherhood".[1]

To Trintignant the Gaullican identity was a civic and cultural identity that one could join into by assimilation; it was an inclusive identity that individuals from around the globe could and should aspire to be apart of. He described the primary goal of Gaullican imperialism to be a great "mission to spread civilisation".[1] In this regard, many contemporary thinkers describe Gaullican nationalism to have evolved into that of "civilisational identity", with Estmerish historian Paige Moss referring to it as a "a mimicry of Solarian identity".[124]

The way in which this approach to nationalism was adopted has been brought into question by theorists from within and without Gaullica.[123] In spite of what the Functionalist belief may have outlined, many policies within the empire were implemented strictly on a racial basis. Blanchiment was a Gaullican colonial policy adopted by the empire and maintained and expanded by the Functionalist regime that encouraged white men in the colonies to marry indigenous women in the hopes of "whitening" their progeny.[125]

Additionally many critics of the theory including Gaullican socialist thinker Éliane Bruguière argue that the functionalist idea of the "civic-cultural identity" was an exportable form of "ethnic nationalism".[126]

Authority

At its core, Functionalism is an authoritian political system because it views any form of differing from the opinion of the sovereign to be detrimental to the good of society.[2] Functionalism espouses the belief that the state exists beyond the structures and institutions of society and is actually a physical representation of collective cultural consciousness.[1] In this regard, it is an extremely statist ideology. In the eyes of the ideology the states' apparatuses exist to serve cohesive functions for the betterment of society and its inhabitants. Rafael Duclerque famously compared the state to the intricacies of machine: "each part is unique, individual and special; but a gear has no purpose unless it is within a grander concert."[117]

Opposed to democracy, liberalism and socialism, Functionalism mandates the investiture of power in a strongly centralised authority.[1][2] Whilst Trintignant exclusively referred to this entity as an absolute monarch, ostensibly the Gaullican Emperor, when implemented in Gaullica the investiture of power was focused in the position of Premier; Rafael Duclerque.

Basile Vaugrenard, a Functionalist jurist, wrote several treatises in which he supported the Parti Populaire's measures of negating the influence of the Senate: "Democracy, the idea of voting in governments, does nothing but foster divisions within society. People become affiliated with political parties, and their identity to a greater collective is superseded by party-membership."[127]

Throughout its existence in dominating politics in Gaullica following the end of the Great Collapse, the Parti Populaire aimed to curtail the influence of the democratic systems of government by numerous means.[117] Initially, numerous political associations were branded as enemies of the state including the SGIO - at the time the second largest party.[16][60] Following this the party granted the position of premier numerous executive powers over the course of late 1919 all the way through 1921.[16] These ranged from the ability to dismiss members of the senate, to dissolving the senate at will, the ability to supersede the senate on its duties of appointments unilaterally as well as complete subvert the institution in regards to assessing the budget. At the conclusion of his term's limit, Rafael Duclerque declared a motion in which his term limits were suspended.[16]

Communauté populaire

Trintignant surmised that "if a state has an institution within it; it serves a purpose. If it served no purpose, it would have no use to the state."[1] Whilst he did argue that you could divide the constituent parts of the nation into as many arbitrary pieces as you wanted, Trintignant settled on four distinct social groups that encompassed all others: the government, the family (or women, depending on publication), the armed forces and the church.[1]

These four social groups are at the forefront of Functionalist belief in the Communauté populaire, (People's Community), the mechanisms used to keep people - and therefore society - united, prosperous and happy. Each of the four social groups had a specific duty in the theories of de Trintignant:[1][128]

- Women/The Family: In functionalist thought, the family was seen as the primary unit of socialisation. Family units had to instil in young people the norms and values of the Gaullican culture at its most basic stage; and needed to continue to repopulate the Gaullican nation. To enforce this in practice, the Parti Populaire offered great incentives for families to continue having children, instituted a far stronger and robust model of welfare for those children, and provided tax rebates to families with many children (as from three or more.) Women were permitted to enter non-traditional areas of employment through a policy known as "national necessity", especially during the time of total war.[129]

- The Church: de Trintignant remarked that "faith builds community and provides direction". In the view of the functionalists, religion, even if not factual, provided a strong sense of communal bond and was the base of all forms of identity that superseded it. As far as they were concerned moral direction, subservience to authority, and these strong communal bonds were best exemplified by Gaullica's largest religion: Solarian Catholicism. Because of its established authority within Gaullica, the Parti Populaire was forced to compromise on issues with the Church. In this regard, whilst the functionalists may have wanted to centralise authority within the secular government, they were forced to maintain clerical involvement in all sectors of society.[130]

- The Military: Viewed both as an honourable institution and an exemplification of human duty as well as a necessity in a view of the way states function, Trintignant viewed the military highly positively.[131] This largely stemmed from his own service. He viewed the military as a defence of the communal body of the nation by itself, and that increasing it's strength would achieve success for the nation. As a realistic ideology, it viewed the strength of a nation to be the predicate to its success.[66] The Parti Populaire adhered to the existing empire's reliance on the military, yet continued its expansion, prestige and dedication to innovation within the military - such as allocating enormous resources to research and development in the field of armoured warfare, aircraft, rocketry and the like.

- The Government: The government, being viewed as an organic entity, and often compared by analogy to the body, found itself as the primary facilitator for all facets of life.[132] Trintignant viewed the government as a "mother for all society" and instilled in it the responsibilities of rearing up the collective children; but also providing work, security, safety, good health and education for all of society. Because of this, he viewed elements of non-compliance as in democratic and liberal societies as weakening this message. To consolidate this vision of a "paternal" state, functionalism in Gaullica worked at eroding away at the elements of democracy within its governing system and sought to entrench itself within power.[16]

These four sections were often compared, via analogy, to the human body. They were argued to work best together for a unified goal, and both Trintignant and Duclerque simplified the explanation by comparing them to the organs of the human body.[132]

Action and conflict

Functionalism is predicated on the necessity of political violence, as an integral part of the mechanism to both create and defend the environment for the "perfect state".[1][2][5] This view on violence is one that glorifies it as a direct aspect of humanity. Trintignant often referred to it as a "natural" state of the human condition; and that violence had served as a legitimate means for settling disagreements, disputes, territorial issues and breaches of the law.[1] In this sense, it was rooted in some of the elements of the applications of Mersenne's biological discoveries to politics.[133]

This predication on legitimate political violence led to the creation of numerous paramilitaries, most famed were those of the Parti Populaire during their rise to power in the 1910s.[12] These were the Chevaliers de l'Empereur and the Veuves de Sainte Chloé, led by Gwenaëlle Cazal, one of Duclerque's most trusted associates. In practice, these organisations were used to intimidate political opponents, beat opposition on the street, instigate violence and carry out terrorist attacks.[12] Once the Parti Populaire took power, both paramilitaries were organised under a new name, the Maréchaussée ("Marshalcy"). Led by Gwenaëlle Cazal, this new police force and party apparatus had the authority and blank cheque to investigate enemies of the movement and state, and "degenerates", and deal with them with impunity. One of their first acts was a purging of labour union leadership, the killing of high-profile SGIO members, and even assassinations of prominent anti-war liberals within Kesselbourg and Hennehouwe.[12]

These principles glorifying violence also translated onto how Functionalism views inter-state relations.[66] A realistic political position in the topics of international relations, Duclerque emphasised the necessity for the projection of power - and that the only "currency respected in the international order is monopolised violence".[117] This view of military action, conflict and violence led to Functionalism preoccupying itself in an ever-increasing armament for an eventual global conflict.[131]

The institution of the military itself was praised, adored and almost venerated by Functionalists.[131] Trintignant, a serviceman himself, viewed the military as a structure to imitate. He praised the meritocratic yet hierarchical nature of the Gaullican military, and exemplified its use as a model for some levels of bureaucratic government. Functionalist attitudes towards the military are universally positive, in both propaganda and legislation. The Parti Populaire increased the funding of the military substantially, including to its pension funds to widows and children.[134]

Economic policies

Functionalism described itself as being anti-capitalist and anti-socialist.[1] Trintignant's writings explicitly reference the ideology as a "syncretic solution to the question of economics", and he himself maintained that capitalism was a system that was inherently unconcerned with the state and socialism was too preoccupied with achieving a stateless society.[1][135] Trintignant wrote within his works that the efficacy of capitalism must be controlled by the state to ensure complete subservience to the Communauté populaire, and that the profits turned for social good and state success rather than economic gain. Socialism, on the other hand, he disparaged as being too "societally destructive" and viewed their ideas of a stateless society to be naïve. One of his proposed purposes of the duties of the state was to deal with the economic concerns of the working class.[1][61]

Duclerque, he himself originally holding left-wing economic views in his youth, was far more vocally critical of capitalism in his remarks and positioned his party as an "alternative to economic determinism".[40] Officially, Duclerque made corporatism the economic policy of the Functionalist movement.[135] He believed in an irrevocable "moral evil" within capitalism, decrying it as an individualistic, materialistic and liberal quest for "infinite profit on a finite world".[40] Duclerque was strongly influenced by Catholic positions on economic justice and tried to reconcile the economic elements of socialism whilst detaching them from their internationalist positions. His corporatism aimed to reconcile the "best of both systems" by placing the state as an arbiter between corporate workers and labourers. Duclerque eventually denounced the socialist idea of class conflict and instead championed the cause of class collaboration.[40][135]

The extent to which Functionalism operated as pro-worker or pro-business fluctuated. Żyścin "Justin" Żowanu, three time Minister of Finance for the Functionalist Regime, was replaced over his opposition to implement "pragmatic policies".[136] Duclerque privately held that "economic ideology isn't important, what the nation requires is". The Parti Populaire backtracked on several of their public positions of the nationalisation of the businesses that many had viewed as being responsible for the Great Collapse, though the threat of nationalisation was utilised to ensure businesses kept aligned to the regime and its "economic realities".[135][136]

Functionalism passed many pro-worker pieces of legislation in its initial period of control, though would often juggle this with the demands of the business sector.[135][136] Within six months of coming to power the Parti Populaire mandated compulsory union membership across Gaullica under the Fédération du travail, a Functionalist trade-union organisation.[137] Despite this, corporate interest was maintained in Functionalist economic policy and the regime later reneged the right to strike on the basis that as the negotiator between workers and business it would ensure equity through the Ministry of Corporations and Labour. Industrial action and worker agitation was a crime punishable by death.[137][61]

Rates of Gaullican unionisation in 1918, prior to consolidation under the Fédération du travail.

The Parti Populaire brought about a series of progressive economic reforms as part of its renegotiation including increases to disability and unemployment benefits and the guaranteeing of paid vacations and sick leave, among other policies.[16] Functionalist social programmes were described as "robust and generous", rivalling or eclipsing all Euclean societies.[39]

One of the most notable elements of the Functionalist economic agenda were numerous immense public works and infrastracture projects to revitalise the economy following the Great Collapse.[137] These included the building of important civilian and military infrastructure in both the metropole and the colonies, including the completion of the highly prestious Trans-Bahian Railway.[138] The Ministry of Public Works oversaw the creation of hundreds of new schools and hospitals as part of this programme. Additionally, Gaullica's hydroelectric power output increased eightfold during the 1920s through the creation of numerous dams across the Aventines.[139]

The desire for economic self sufficency was also a driving force behind the pragmatic approach Functionalists took to the economy, but their belief in self-sufficiency extended to all aspects of the empire as a single entity.[135]

Modern commentators have tried to concisely describe Functionalist economic policy. According to Magnus Fleischmann the economy displayed "clear elements of dirigiste thinking, though that style of economic thinking was first used to describe Gaullican economic policy post-Great War. Most modern scholars agree that Functionalism is strictly corporatist in economic terms, though "highly pragmatic".[140]

Nostalgic future

Functionalism maintains a view on society that has been described as a synthesis of palingenesis and modernism.[141] This synthesis is best exemplified in a declaration from Duclerque, who during his first speech as Premier in 1919 declared that to prepare Gaullica for the future it needed to "born anew".[40] The Functionalist view of modernism was fixated on scientific and industrial advances, praising the modern world for the great leaps of human ingenuity and intelligence in the creation of new fields such as aviation, cinema and industrial management.[141] In this way, Functionalism selectively chose what elements of modernism it deemed as ideal for a national rebirth whilst rejecting those it did not deem suitable. For instance, Functionalism rejected the sceptical nature of the modernist movement's uncertainty in science and dismissal of religion.[141]

Ultimately, Functionalism viewed societies developing on a path towards an idealised goal of perfection.[1][141] The developments of the modern era were espoused as necessary and to be celebrated if they could be controlled by a benevolent state and utilised for righteous purposes, as opposed to contribute to a "culture of decadence".[142] Functionalists were highly critical of the individualistic aspects of modernism as an affront for the human collective, and aimed to purge these elements from their movement.[143] Instead they aimed to bring about the concepts of modernism they found agreeable in the national reawakening of Gaullica, whereby the nation would finally "purge itself" free of the corruptions of liberalism, socialism and individualism and recreate new classes of "dedicated warriors to civilise the world".[1][117]

Such a synthesis of ideas was named the "Nostalgic Future" by Functionalists, indicating that there would be elements of a traditional past in a better tomorrow. Much of this was related to the Gaullican idea of la Perpétuation and the need to continue it, harkening back to a proposed continuous existence of knowledge that had been disrupted by the Age of Revolutions.[144][145]

Aesthetics and culture

Trintignant described Functionalism as a "manner of being" as opposed to a mere political ideology.[8] Duclerque, in the charter of the Parti Populaire, stated: "Functionalism is more than a political ideology; it is a movement of the human being to achieve perfection. Perfection in the arts, physical, political and spiritual."[117] Following its arrival on Gaullica's political landscape by 1890, cultural movements arose within academia to try to apply Functionalist principles to the arts and sciences. The most forefront of these movements was the Futurism movement, which became the cultural wing of the Functionalist political machine.[50]

Jürg Ochsner explained Functionalism's sculpture of culture through his idea of cultural hegemony, arguing that the Functionalists knew that by controlling culture they would be able to shape the views of society at large in a way amenable to them.[146]

The Parti Populaire set up a Ministry of Culture to direct and encourage artists to develop the ideas of the "Nostalgic Future", the state-as-organism, and the development of all aspects of life through technology.[145][142]

Architecture

An example of the Beaux-Arts style.

An example of the Art Nouveau style.

An example of the Art Deco school.