Vetuslithic Age

This article is a work in progress. Any information here may not be final as changes are often made to make way for improvements or expansion of lore-wise information about Gentu. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, contact User:Philimania. |

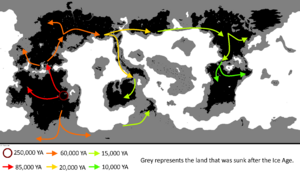

Proposed map of the Great Migration, according to artifacts found in certain regions (its accuracy is disputed). | |

| Period | Prehistorical Era |

|---|---|

| Dates | 2.5 mya-8,000 BCE |

| Preceded by | Septun epoch |

| Followed by | Novalithic Age |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Gentu and Gentish human history (Hodiernus epoch) |

|---|

| ↑ before Homo (Septun epoch) |

|

Prehistorical Era (one-era three-age system) |

|

| Ancient Era |

|

| Antiquity Era |

|

| Middle Era |

|

| Modern Era |

|

| ↓ Future |

The Vetuslithic Age, also known simply as the Vetuslithic, or the Old Stone Age is a period of the Prehistorical Era characterised by the emergence of the earliest stone tools that covers 99% of the period of human technological prehistory. It extends from the earliest known use of stone tools by hominins c. 2.5 million years ago, to the end of the Great Migration c. 10,000 years ago.

The Vetuslithic Age preceded the Novalithic Age. During the Vetuslithic Age, hominins grouped together in small societies such as tribes and subsisted by gathering plants, fishing, and hunting or scavenging wild animals. The Vetuslithic Age is characterized by the use of knapped stone tools, although at the time humans also used wood and bone tools. Other organic commodities were adapted for use as tools, including leather and vegetable fibers; however, due to rapid decomposition, these have not survived to any great degree.

Humankind gradually evolved from early members of the genus Homo, such as Homo rectus, who used simple stone tools, into anatomically modern humans as well as behaviourally modern humans by the Upper Vetuslithic. During the end of the Vetuslithic Age, specifically the Middle or Upper Vetuslithic Age, humans began to produce the earliest works of art and to engage in religious or spiritual behavior such as burial and ritual. Conditions during the Vatuslithic Age went through a set of glacial and interglacial periods in which the climate periodically fluctuated between warm and cool temperatures resulting in the Great Migration. Archaeological and genetic data suggest that the source populations of Vetuslithic humans survived in sparsely-wooded areas and dispersed through areas of high primary productivity while avoiding dense forest-cover. By 60,000 years ago, Humans had migrated to most of Hesterath and the sunken continent of Subarctica, and would have entered Alabon around the same time. At around 20,000 years ago, most of Trimeshia had been inhabitated by Humans by crossing the X land bridge and additionally, wandered in to northern and central Flonesia. By 15,000 years ago, humans had reached the Domicas as evidence of humans were found there and most of Flonesia would have been migrated to as well as X from Subarctica. At around 10,000 years ago, South Domica would have been inhabitated marking the end of the Vetuslithic and the beginning of the Novalithic.

Etymology

The term "Vetuslithic" was coined by archaeologist X in 1854. It derives from Alarican: vetus, "old"; and Pylosan: λίθος, lithos, "stone", meaning "old age of the stone" or "Old Stone Age".

Human way of life

Nearly all knowledge of Vetuslithic human culture and way of life comes from archaeology and ethnographic comparisons to modern hunter-gatherer cultures such as the X who live similarly to their Vetuslithic Hextern predecessors. The economy of a typical Vetuslithic society was a hunter-gatherer economy. Humans hunted wild animals for meat and gathered food, firewood, and materials for their tools, clothes, or shelters.

Human population density was very low, around only 0.4 inhabitants per square kilometre (1/sq mi). This was most likely due to low body fat, infanticide, women regularly engaging in intense endurance exercise, late weaning of infants, and a nomadic lifestyle. Like contemporary hunter-gatherers, Vetuslithic humans enjoyed an abundance of leisure time unparalleled in both Novalithic farming societies and modern industrial societies. At the end of the Vetuslithic, specifically the Middle or Upper Vetuslithic, humans began to produce works of art such as cave paintings, rock art and jewellery and began to engage in religious behavior such as burials and rituals.

Distribution

At the beginning of the Vetuslithic Age, early humans such as the Homo rectus were located primarily in east and north Naphtora; and southern Oranland. Most early human fossils dating earlier than 1 million years ago are found in the regions. More specifically in places such as X, X, X, Paqueonia and Paloa.

Early groups of humans began leaving their origin point in east Naphtora c. 2 million – c. 1 million BP and settling to the north of the continent and southern Oranland. The most prominent human species were the Homo nupecirni who inhabited all regions and migrated to the Limu mountain range c. 1.4 million BP before moving to the Hesterath lowlands c. 1.1 million years ago. By the end of the lower Vetuslithic, early humans had reached central Hesterath with some evidence of human habitation in Eudocia and X. Very little fossil evidence are known to exist in central Hesterath. But it is believed that humans that inhabited the region by 500,000 BP were the Homo alifax, Homo nuperni, and the Homo amittere. In Oranland and Naphtora, the dominant and the most populous human species was the Homo aetas. There is no evidence of humans in the Domicas, Flonesia, Alabon, or in Trimeshia during this time period.

During the Middle Vetuslithic, early Mutamni humans known as the Weisserfluss people begun entering northern Hesterath around 190,000 BP. The fates of these early colonists, and their relationships to modern humans, are still subject to debate although a popular theory is that they were an genetic offshoot of the Homo alifax. In Alabon, the earliest Vetuslithic site in X dates back to around 170,000 BP making it the earliest known evidence of human habitation on the continent. By the end of the Great Migration 10,000 to 7,000 BCE, human species except the Homo captiosus and Homo validus went extinct due to the rapid change in climate brought about by the end of the Hodiernus Ice Age. By 7,000 BP, Homo captiosus had settled on most of Gentu while Homo validus survived on the Hesterlon Peninsula before goin extinct c. 5,300 BCE during the Novalithic Age.

For the duration of the Vetuslithic, human populations remained low, especially outside the equatorial regions. The entire population of Oranland was estimated to be in between 90,000 to 150,000 individuals, in 400,000 BP, it was even lower at 4,000 to 6,000 individuals between 1 mya to 800,000 BP.

Technology

The earliest known Vetuslithic stone tools dates to around 2.6 million years ago. Tools dating to this period includes choppers, burins, and stitching awls. Lower Vetuslithic humans used a variety of stone tools, including hand axes and choppers. Although they appear to have used hand axes often, there is disagreement about their use. Interpretations range from cutting and chopping tools, to digging implements, to flaking cores, to the use in traps, and as a purely ritual significance, perhaps in courting behaviour. Choppers and scrapers were likely used for skinning and butchering scavenged animals and sharp-ended sticks were often obtained for digging up edible roots. Ostensibly, early humans used wooden spears as early as five million years ago to hunt small animals, much as their relatives, chimpanzees, have been examined to do in west Naphtora. Further inventions such as nets (c.20,000 BP), and the bow and arrow (c.30,000 BP) were also made. Moreover, early dogs were domesticated between 30,000-14,000 BP, most likely to aid in hunting.

The first boat—or raft—was possibly invented c.840,000-810,000 BP by Homo rectus to travel over large bodies of water, which may have allowed a group of then to reach the island of Farata and evolve into the small hominin Homo faratium. The possible use of rafts during the Lower Vetuslithic may indicate that Lower Vetuslithic hominins such as Homo rectus were more advanced than previously believed and may have even spoken an early form of language. Supplementary evidence from Homo validus and modern human sites located around the Zestoric Sea, such as X, has also indicated that both Middle and Upper Vetuslithic humans used rafts to travel over large bodies of water for the purpose of settling other bodies of land.

Social organisation

The social organisation of Lower Vetuslithic societies remains largely unknown to scientists, though Lower Vetuslithic hominins such as Homo rectus are likely to have had as slightly more complex social structures than chimpanzee societies. Later human species such as Homo aetas or Homo nuperni may have been the first people to invent central campsites or home bases and incorporate them into their foraging and hunting strategies like contemporary hunter-gatherers, possibly as early as 1.5 million years ago; however, the earliest concrete evidence for the existence of home bases or central campsites (hearths and shelters) among humans only dates back to 700,000 years ago.

Meanwhile, Middle, and Upper Vetuslithic societies were possibly fundamentally egalitarian and may have rarely or never engaged in organized violence between groups. Some Upper Vetuslithic societies in resource-rich environments (such as Hextern societies in Eudocia, in what is now X) may have had more complex and hierarchical organization (such as societies with a pronounced hierarchy and a somewhat formal division of labour) and may have engaged in endemic warfare. However, some argue that there was no formal leadership during the Middle and Upper Vetuslithic: like contemporary egalitarian hunter-gatherers such as the X, societies may have made decisions by communal consensus decision making rather than by appointing permanent rulers such as chiefs or monarchs. Several theories to explain the apparent egalitarianism have arisen, most notably the Volkist Idea of Primitivity. Jonathan Turner (1976) has hypothesized that egalitarianism may have evolved in Vetuslithic societies because of a need to distribute resources such as food and meat equally to avoid famine and ensure a stable food supply. Even so, other sources claim that most Vetuslithic groups may have been larger, more complex, sedentary, and warlike than most contemporary hunter-gatherer societies, due to occupying more resource-abundant areas than most modern hunter-gatherers who have been pushed into more marginal habitats by agricultural societies.

Art and Music

The earliest undisputed evidence of art during the Vetuslithic dates back to the Middle Vetuslithic. Sites such as Vinado Cave in X in the form of bracelets, beads, and rock art. Upper Vetuslithic humans produced works of art such as cave paintings, animal carvings, and rock paintings. Upper Vetuslithic art can be divided into two broad categories: figurative art such as cave paintings that clearly depicts animals (or more rarely humans); and nonfigurative, which consists of shapes and symbols. Cave paintings have been interpreted in a number of ways by modern archaeologists. The anthropologist Frederick Richard has suggested that Vetuslithic cave paintings were indications of shamanistic practices because the paintings of half-human, half-animal figures and the remoteness of the caves are reminiscent of modern hunter-gatherer shamanistic practices. Symbol-like images are more common in Vetuslithic cave paintings than are depictions of animals or humans, and unique symbolic patterns might have been trademarks that represent different Upper Vetuslithic ethnic groups.

The origin of music in the Vetuslithic for the time being, is unknown. The earliest forms of music probably did not use musical instruments other than the human voice or natural objects such as rocks. This early music would not have left an archaeological footprint. Music may have developed from rhythmic sounds produced by daily chores, for example, cracking open nuts with stones. Maintaining a rhythm while working may have helped people to become more efficient at daily activities. During the Upper Vetuslithic, humans used flute-like bone pipes as musical instruments, and music may have played an influential role in the religious lives of Upper Vetuslithic hunter-gatherers. As with modern hunter-gatherer societies, music may have been used in ritual or to help induce trances. In particular, it appears that animal skin drums may have been used in religious events by Upper Vetuslithic shamans, as shown by the remains of drum-like instruments from some Upper Vetuslithic graves of shamans and the ethnographic record of contemporary hunter-gatherer shamanic and ritual practices.

Religion and beliefs

TBA

Diet and nutrition

TBA

See also