Yamabe Oshimaro: Difference between revisions

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

===Pleading=== | ===Pleading=== | ||

The court first focused on the question of Yamabe's | The court first focused on the question of Yamabe's allegiance. The Navy contended Yamabe did not claim benefit of alien and should be tried as a subject, for treason. The question was important as a charge of treason against a foreigner is legally impossible due to lack of allegiance. Bjum Hwêr, barrister, argued this point and asked the case be dismissed with prejudice, for a "legal error of substance" (灋之據有實失). The prosecution provided that Yamabe had joined the marine corps as a subject, and the defence returned that the Navy's arguments are not legally manifest. The defence proved that marines can be foreigners during service, attested by their lack of warrants from the militia and enrolments in [[Domestic Records (Themiclesia)|household records]], after discharge. On Mar. 31, the Navy was ordered to produce counter-arguments; the prosecutors pled {{wp|imparlance}}, which the court overruled. The judges sustained the demurrer to Yamabe's legal allgeiance and rejected the indictment for treason. | ||

Desperate for information, the Navy ordered agents to monitor Yamabe for incriminating evidence. Ree anticipated this and stationed solicitors at Yamabe's side. On Apr. 7, solicitor Mak | Desperate for information, the Navy ordered agents to monitor Yamabe for incriminating evidence. Ree anticipated this and stationed solicitors at Yamabe's side. On Apr. 7, solicitor Mak M′in staged a conversation with Yamabe to confess a fictitious relationship with the Dayashinese high command. When session resumed, the Navy presented the staged conversation as evidence, and Ree demanded the case be dismissed with prejudice. The court did not dismiss the case but expelled the prosecutors. The Bar was scandalized by their misconduct and voted to disbar the prosecutors. With new prosecutors, the Navy pushed for {{wp|venire de novo}}, but Klung, barrister, argued the Navy was at fault for the interruption and not entitled to a new trial. Klung further requested, unsuccessfully, the indictment be dismissed. The court ordered the parties to join at issue. | ||

===Joinder and trial === | ===Joinder and trial === | ||

Revision as of 00:53, 19 October 2020

Yamabe no Oshimaro | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | 山部押麻呂 |

| Born | November 30, 1919 |

| Died | December 2, 2000 (aged 81) Nakaya, Dayashina |

| Buried | Onakata, Dayashina |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Imperial Dayashinese Army (cover) Imperial Special Operations Group (actual) |

| Years of service | 1937 – 1960 |

| Rank | Major |

| Battles/wars | Pan-Septentrion War |

| Spouse(s) | 高町古真子 (Takamachi Komako, m. 1938) |

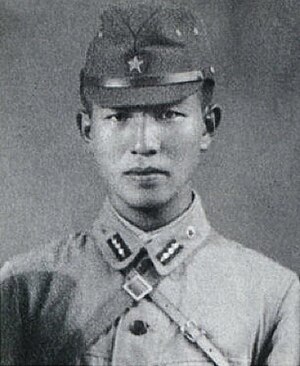

Yamabe Oshimaro (Dayashinese: 山部押麻呂/やまべのおしまろ, also Yamabe no Oshimaro, Nov. 30, 1919 – Dec. 2, 2000) was a Dayashinese soldier of the Pan-Septentrion War and author of several books relating to it.

Personal life

Birth and early life

Yamabe Oshimaro was born on November 30, 1919 to Yamabe Komomaro (山部薦萬侶, Dayashinese: やまべ の こもまろ) and Nijou Uchiko (二條內子, Dayashinese: にじょう うちこ). His father was a mid-level military officer in the Imperial Dayashinese Army, while his mother was from a wealthy Dayashinese industrialist lineage. He was born third of five boys, and fifth of nine children in total. His family was well-to-do before and throughout the war, though his parents raised him in a thrifty manner, believing that pampering him with luxury would do no good for his future career, certainly a military one.

Physique

While he was not the tallest person to have lived in Dayashina as sometimes believed, his height has been a subject of discussion after the PSW.

His father was noted as an large man, standing 6' 2", and his mother was then also unusually tall for a Dayashinese woman, at 5' 11" (181 cm); the couple was considered a good match (amongst other factors) for their height. Oshimaro grew up to be a prodigious 6' 5" (196 cm), the tallest amongst his siblings. According to himself, he was rarely not the tallest person in any setting, and he grew up "looking down on others".

For his height, Oshimaro had been given special duties at his school and the IDA. In the earlier part of his military service he was noted to be immensely strong, while also an avid sportsman. His great strength was utilized at his unit as a conveyor of weapons and ammunitions, whose transport otherwise required multiple individuals. His enlistment records at the Themiclesian Marines suggest that he weighed 108 kg (240 lbs), which was 2 kg short of obesity.[1] According to other members of his unit, he was nicknamed the "beefcake", and again his great strength and willingness to use it helping others made him a popular individual in his Themiclesian unit.

Infiltration

After he was settled by the Foreign Office in Nem-tl′jang County (南昌), Ljoi Prefecture (陲), he sought enlistment with the Marines, whose operations would give him a pretext to approach the palace and access to weapons. To this end, he overcame several obstacles. The Marines did not recruit in Ljoi, necessitating his travel to Prjin Prefecture (濱); however, train tickets were difficult to purchase due to ongoing warfare, so he wrote to the Governor of Ljoi for passage. When he arrived in Prjin, he was approached by Gwjang Kr′ang (王康), an agent of the Foreign Office, which believed his movement was suspicious. Gwjang pretended to be a fellow traveller and obtained some information over a meal. He then offered to show Yamabe to the Marines' recruitment offices, where he communicated to the officer in charge his suspicions. The recruitment officer rebuffed him, since "beggars can't be choosers". This statement referred to the Marines' lacklustre recruitment when most able-bodied men were on conscription notice from the Ministry of War. The agent plainly stated that Yamabe could join his local regiment if he wanted to serve under Themiclesian colours, which rendered his great effort to join the Marines peculiar.[2]

Trial

Arraignment

On Nov. 2, 1941, Yamabe was sent to the law side of the Exchequer Court (內廷, nubh-lêng). The Themiclesian Navy committed all allegations of treason and felony for trial at this court, which is ordinarily concerned with disputes in excise, customs, and amercements. While the Navy possessed its own version of the court-martial, held by its captains and the naval tribunes, its jurisdiction did not extend to crimes committed in domestic territory. As the court was in vacation, his capture reached the newspapers, prompting his financially well-off parents in Dayashina to retain serjeant-at-law Chao Ree (黎兆), GC to represent him. Chao Ree was a partner in Ree, Ree, and Ree (三黎士師所, s.rum-ri-dzrje′-srji-skrja′), then one of Themiclesia's most renowned criminal defence firms.

He was formally arraigned on Feb. 10, 1942 and stood indicted on 17 murder charges, 24 assault charges, and high treason. Ree led the defence, with Yamabe absent, prior to trial; on the 22nd, he demurred to all murder and assault charges as "acts prescribed by a foreign ruler". That is, on the grounds that neither were Themiclesian soldiers on trial in foreign states for acts against them, so Yamabe ought not be tried for these actions. On the following day, the public disorder charges were confessed. On Mar. 5, Yamabe appeared in court for the first time and entered a not guilty plea to treason. Themiclesian law required all charges to be answered before the court proceeded to decide demurrers.

Pleading

The court first focused on the question of Yamabe's allegiance. The Navy contended Yamabe did not claim benefit of alien and should be tried as a subject, for treason. The question was important as a charge of treason against a foreigner is legally impossible due to lack of allegiance. Bjum Hwêr, barrister, argued this point and asked the case be dismissed with prejudice, for a "legal error of substance" (灋之據有實失). The prosecution provided that Yamabe had joined the marine corps as a subject, and the defence returned that the Navy's arguments are not legally manifest. The defence proved that marines can be foreigners during service, attested by their lack of warrants from the militia and enrolments in household records, after discharge. On Mar. 31, the Navy was ordered to produce counter-arguments; the prosecutors pled imparlance, which the court overruled. The judges sustained the demurrer to Yamabe's legal allgeiance and rejected the indictment for treason.

Desperate for information, the Navy ordered agents to monitor Yamabe for incriminating evidence. Ree anticipated this and stationed solicitors at Yamabe's side. On Apr. 7, solicitor Mak M′in staged a conversation with Yamabe to confess a fictitious relationship with the Dayashinese high command. When session resumed, the Navy presented the staged conversation as evidence, and Ree demanded the case be dismissed with prejudice. The court did not dismiss the case but expelled the prosecutors. The Bar was scandalized by their misconduct and voted to disbar the prosecutors. With new prosecutors, the Navy pushed for venire de novo, but Klung, barrister, argued the Navy was at fault for the interruption and not entitled to a new trial. Klung further requested, unsuccessfully, the indictment be dismissed. The court ordered the parties to join at issue.

Joinder and trial

During Yamabe's trial, the 4th and 5th Regiments have started to identify infiltrators. The campaign is estimated to have killed as many innocent soldiers as infiltrators. The Admiralty ordered the 4th Regiment to make themselves available for jury duty for the treason trial. The prosecution moved that a jury should be summoned from Yamabe's regiment, which was indignant at his actions; however, Ree expounded the issue was one of law, not of fact, which in the Exchequer results in a trial by bench. The judges agreed and directed the Navy to accept this mode of trial. The Navy was later proven to have schemed of using the regiment's rage to secure a conviction.

The prosecution argued that Yamabe, no matter his nationality, owed allegiance to the Themiclesian crown after he had surrendered to the Themiclesian Army and accepted the purse of 600 hmrjing as advertised. The defence maintained that Yamabe did not owe allegiance by his surrender, at best becoming stateless. On May 15, parliament resumed sitting, and the Navy Secretary passed a bill to naturalize all members of the two regiments that were not yet naturalized. This did not retroactively apply to Yamabe, though his name was on the bill.[3]

During closing statements, Yamabe asked to address the court personally. Ree gave him a very lengthy script that described him purely as a Dayashinese soldier, protected by the Eisenmaat Convention; he initially followed the script but soon deviated from it, inserting statements that disparaged the Emperor, his court, and the country's future generally. The Court stopped and imprisoned him several times, but each time he was released, his statements grew more extreme. The Navy thought his tactics amounted to a filibuster. The prosecutors asked the Court not to remand the defendant to confinement, so his "treasonable" statements could be heard. Ree, in the pit, could not bar his client's speech.[4]

Assassination attempt

On Jun. 2, two marines of the 4th Regiment broke into the marshalsea in which Yamabe was held, apparently intending to assassinate Yamabe. Solicitors by Yamabe took several shot, though none fatally. They testified that the two had spoken words indicating their intentions. Ree capitalized on the argument that Navy sent these assassins, asking the case be dismissed due to gross misconduct of the prosecuting party. The prosecutors objected that this intrusion had nothing to do with them. The Court concurred with Ree, mindful of the prosecution's previous tactic, and dismissed the case with prejudice, acquitting Yamabe of treason and the public disorder charges that have already been confessed. The Navy requested permission to appeal the judgment, but the court refused. It then discharged Yamabe and proposed to the Gwên Prefecture (where Yamabe lived) police to monitor Yamabe.

Later life

Yamabe was released from house arrest in 1946, after the Dayashinese Empire surrendered. He returned to the Dayashinese military in the late 40s and continued work for his native country in various fields.

Work

Yamabe wrote of his experiences in Themiclesia in his autobiography Tomorrow, published in 1970. The book's cover was an image of him in the Themiclesian Marines' frock coat, the photo long after he had returned to Dayashina. When the book was printed in Themiclesia, the publisher was concerned that the cover might be offensive to some Themiclesians and wanted it altered; however, after legal consultation, Yamabe insisted that the publisher use the cover image. As expected, some veterans of the PSW wrote critically of this image on newspapers and asked that it should be sold in plain envelopes, but the Kien-k'ang High Court issued a per curiam that the uniform was his property and not an example of obscene clothing, so there is no objection to his wearing it publicly or depiction in it.

In 1993, Yamabe's infiltration, with reference to Tomorrow, was filmed into a movie of the same name. Yamabe himself was retained as a consultant and was reportedly very surprised that the film did not cause much outrage in Themiclesia. To the few critics of the film on historical and emotional grounds, the Film Board of Themiclesia asserted that a movie is, in the first place, a work of art, and it should not be judged as a documentary. Education Secretary Kjaw said that "movies appeal to a human aesthetic regardless of nationality." It is reported that Emperor Hên', who was the intended victim, also watched the film in a private screening; he said that the actor portrayed him more bravely than he was and that the set did not resemble the place the assassination attempt took place at all.

Quotes

- "I have a closet where I keep all my uniforms, including the Themiclesian one. You can tell it apart from all the others instantly because it's made out of fine Tyrannian wool. I thought it was a little ironic that Themiclesian marines should wear a product made by their mortal enemy's country. But then I also thought it was a very Themiclesian thing to do. It's cheaper and better than many domestic fabrics, so what's not to like?"

Notes

- ↑ This was an absolute weight ceiling regardless of height.

- ↑ The agent recalled loudly said in the recruitment office, "If his intention was simply to serve, he could do it in a hundred other units. He had to pester his magistrate for permission to buy a ticket just to come here and locate this building with his clumsy Shinasthana, when Prjin's militia had posters and roadsigns everywhere. Why make this absurd effort to join your ranks in particular? He is a surrender from the IDA, not the IDN; he is not joining you for reasons of familiarity. I say, his motives are ultierior. There is something attractive about you over all the others, and we at the Foreign Office think you should not fail to be judicious." When Yamabe protested that his intentions were pure, Gwjang asked him to provide a simple reason why he made this choice. Yamabe said that he liked the unit's history. Gwjang remarked that virtually all recruits choose their units based on convenience, not an academic interest in the unit, further showing the extent of Yamabe's peculiarity.

- ↑ Up to this point, those desiring naturalization submitted a peition to the Council of Ushers declaring their wish to become subjects of the Themiclesian crown, and an act of parliament would be passed (generally for hundreds at once) to recognize their citizenship. Yamabe joined the Marines without formally petitioning for citizenship, which he thought was automatically granted upon accepting the 600 hmrjing purse.

- ↑ Attorneys sat in a sub-level pit, before the bench, while not speaking.