Ziba

| Ziba | |

|---|---|

ziba | |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ziba] |

| Region | Northern Southeast Coius |

| Ethnicity | Dezevauni people, Dhavoni people, Gowsas |

Native speakers | ~200,000,000 (2020) |

Zibaic | |

Standard forms | Harmonised Ziba (Dezevau)

|

| Dialects |

|

| Ziba script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Ziba Harmonisation Agency (Dezevau) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | zib |

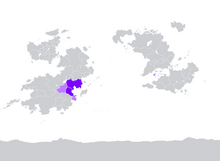

Countries where Ziba is an official or national language Countries where Ziba is a recognised or regional language but not an official or national language | |

Ziba (![]() , ziba, IPA: [ziba]) is the only extant language of the eponymous Zibaic language family. It originated in and is the main language in Dezevau and northern Lavana, and also has legal recognition in Hacyinia and Carucere. It is spoken natively by over 200 million people, making it the fifth language in the world by native speakers, and a further 100 million or so speak it non-natively.

, ziba, IPA: [ziba]) is the only extant language of the eponymous Zibaic language family. It originated in and is the main language in Dezevau and northern Lavana, and also has legal recognition in Hacyinia and Carucere. It is spoken natively by over 200 million people, making it the fifth language in the world by native speakers, and a further 100 million or so speak it non-natively.

Ziba originated in southwest Dezevau several millennia ago, possibly as a contact language. It spread by trade and diplomacy among the region's city-states and other polities, as well as through migration, and association with Badi. In the medieval period, in large areas of northern Southeast Coius, Ziba was used in public, commercial, political, religious and diplomatic life, but coexisted with a variety of languages which were natively spoken at home, in circumstances of diglossia. At least in southwest Dezevau and among some classes, however, it was also a domestic language.

The Aguda Empire, founded in 1476, established Ziba as the official language throughout its territories, using it in administration, spreading it through commerce, deepening its Badist association, and generally promoting it as part of its assimilative policies. The state of diglossia collapsed across much of the Aguda Empire's territory, in favour of Ziba monolingualism. Ziba acquired more ethnic-political implication as a result of the empire's policies. The Aguda Empire also conducted early efforts at language reform and standardisation, with the Ziba dialect continuum converging considerably, and the koiné Agudan Ziba becoming the basis for virtually all later prestige dialects of Ziba. During the colonial and post-colonial periods, Ziba lost much of its status and reach outside of present-day Dezevau and Lavana, as colonial or other national languages were promoted instead. It remains an important regional language, with many of its neighbours retaining loanwords from it, and it being the working language of the Brown Sea Community.

Ziba is an agglutinative language, with a great deal of suffixation to create new nouns and adjectives, sharing similarities in this with the neighbouring Vehemenic languages. Verbs, in comparison, exist simply within a SVO sentence structure. Ziba's possible roots as a contact language, and its storied use as a second language in the public sphere may be linked to its simple grammar and small phonemic inventory; it has twelve consonants and five vowels (monophthongs, which can form a further twelve diphthongs). Its inventory is unusual, however, in not having any rounded vowels, unvoiced consonants/voicing distinction, and a number of other features which are very cross-linguistically common. Most Ziba is written in the Ziba script (cf. Carucerean Ziba), which is somewhere between an alphabet and an abugida; it has had a very close phonetic correspondence since the orthographic reforms of the Aguda Empire.

History

Old Ziba

Old Ziba is the oldest attested form of Ziba, with conjectural reconstructions of its ancestor being referred to as Proto-Zibaic. Writing in Old Ziba script has been discovered mostly in southwestern Dezevau, in the lower Zigiava and Buiganhingi river basins, in areas associated with the Dhebinhejo Culture; it is possible it was spoken more widely. The oldest surviving inscriptions are generally carvings on inorganic materials such as stone, dating to between around 1000 BCE and 1 BCE. Surviving attestations are sparse and fragmentary; it is likely that most writing occurred on organic materials, which decayed in the warm and humid conditions of the region.

Though there is still much unknown about Old Ziba, it was very different to later forms of Ziba. It was an inflectional language, with the Old Ziba script using an assortment of pictograms and an abugida for content words, and only the abugida for function words; the abugida elements developed into Ziba script, with pictograms largely being lost in the transition to Middle Ziba. It is unclear whether Old Ziba had a larger or smaller phonemic inventory than modern Ziba, as it is unclear whether the use of different letters was regional or stylistic variation, or actually representative of phonemic distinction. In some cases, the Old Ziba script was also used to write other Zibaic languages, though these went extinct by the first millennium CE. Though Old Ziba is not at all mutually intelligible with modern Ziba, a considerable amount of modern Ziba vocabulary can be traced directly to Old Ziba.

Old Ziba was used for a variety of purposes, including commercial recordkeeping, religion, letter sending, and perhaps even decoration or signage. As in virtually all ancient societies, literacy was limited to a minority of powerful, wealthy or educated people, so given the dearth of surviving material, its everyday usage is difficult to attest to. With the language spreading to or taking root in the lower Bugunho basin, the Zedenge valley and other areas, it was particularly its association with Badi and its use for trade that became prominent. As the language transitioned into being the high variety in a widespread diglossia, and as it acquired many of the features common to contact languages (such as more analytical grammar and simplification of irregularities), linguists mark the end of Old Ziba and the beginning of Middle Ziba around 500 to 750 CE.

Middle Ziba

Middle Ziba (sometimes called Market Ziba), as the common language of the increasingly wealthy and populous Dezevauni city-states, spread through its use in trade and diplomacy, as well as (to a lesser extent) through its customary usage in Badi. A large diglossic area was established across northern Southeast Coius, with Middle Ziba as the high variety, and a variety of local languages (including Kabuese, Kachai and Ywe) as low. In a few areas, often communities where slaves, merchants or commingled refugees or economic migrants settled, it took over as the sole language.

The spread of Middle Ziba was associated with great linguistic change. In terms of grammar, it moved away from inflection towards analysis and agglutination, lost syntactic irregularities associated with particular words, and converged the morphology of different word classes (nouns, adjectives and verbs). It also experienced a variety of sound changes, often diverging in different dialects, to the extent that a continuum may have been formed. Lexically, it acquired many loanwords, both from other trade languages and from the low varieties in the diglossias it was part of. Pictographic elements in script fell entirely out of regular usage, and the Middle Ziba script was generally simpler and more stylistically regular than the Old Ziba one. This may have borne relation to generally higher levels of literacy in the region at the time.

Middle Ziba's status ebbed and flowed with the Dezevauni city-states, whose relative stability for some centuries saw also a relatively stable and slowly growing diglossia exist over much of eastern Coius for several centuries. The relationship between Badi and Ziba declined in importance over time, as Badist communities normalised the use of other languages, even as Middle Ziba got steadily further away from the Old Ziba which was first associated with Badi. The relationship would be strengthened by the advent of the Aguda Empire, however, whose strong religious character was combined with programs of linguistic, cultural, ethnic, economic, etc. assimilation.

Aguda Empire

Early Aguda Empire

The Aguda Empire, as established in 1476, came from the Ziba-speaking world. Initially, its court used the dialect used in Gobobudi, from whence its founders had come, but as it expanded, its programmes brought speakers of different dialects and different (diglossic) low languages together. A distinctive Agudan Ziba emerged first as a koiné used in the imperial court, becoming more widespread with the growth of Dabadonga, the new capital city.

The Aguda Empire used Ziba as its language of administration, and through its encouragement of commerce, also spurred the use of Ziba that way. The centrality of Badi to its ideological programme meant that it engaged with populations in local languages for proselytic purposes, but Ziba was the main Badist language, in terms of scripture, discourse, and so on. Organically, Agudan Ziba's role as a koiné grew, and it became the norm throughout the governing class.

As the Aguda Empire became more established, and as economic and cultural integration accelerated, diglossia collapsed in favour of Ziba monolingualism in the empire's core regions. Though a slow process, it was noted with approval by the imperial government, though it was not seen as something that it was sensible to interfere with as a matter of policy, inasmuch as it would be more trouble than it was worth to monitor what language people used in their own homes.

Aguda Reforms

Duazaiginhe, elected in 1563 as the fifth zeja (emperor) of the Aguda Empire, initiated and promulgated a number of linguistic policies and reforms; Agudan Ziba most often refers to the form of the language that existed from their reign until the end of the empire and the advent of the colonial period. Duazaiginhe wrote that their motivation for language planning was twofold. Firstly, there was a need for a unified, formal, standard language, to promote cultural unity and to prevent legal ambiguity across the empire (though they did not envision that adoption needed to be compulsory or complete outside of the legal system). Secondly, they saw many of the features of Middle Ziba (or at least some dialects thereof) to be confusing, unnecessarily complex or antiquated, wasting time and resources.

Similar views were held by previous zejas and others in government, but wars and other matters had occupied governmental attentions for much of the time prior to Duazaiginhe's ascension. They commissioned a council of scholars to draft reforms and standing policies, with the council doing most of the work, though they also had personal involvement in the process. The reforms came out in three main waves, some years apart, the last mainly being promulgated by Duazaiginhe's successor. Their effects were wide-ranging, though some features fell quickly out of usage, and on Duazaiginhe's insistence, were often retracted where this occurred, as so to preserve legitimacy and integrity. Historically, linguistic reform is rarely adopted in vernacular usage, especially in the premodern era, so the fact that even a few basic features of these reforms survived makes them unusually successful. Features included the authoritative definition of the script (which survives to this day), the preferencing of particular words (over other synonyms, especially loanwords) and official pronunciation guides, including permissible dialectal variations. Materials from the reign of Duazaiginhe have been invaluable for the historical linguistic study of Ziba, though the practice of rescinding unsuccessful elements of the reforms has made it difficult to establish what was official at any one time or not.

On the whole, the reforms heralded a more interventionist and assimilationist attitude by the Aguda government on language policy, though the Badist religion always remained its ideological mainstay.

Colonisation

Colonisation of the Ziba-speaking world, primarily by Estmere and Gaullica, resulted in a decline in the language's prestige and usefulness, as the Aguda Empire's territories and sphere of influence were taken and carved up. In particular, the reorientation of trade to the seas and the creation of borders which barred trade were detrimental. In the remaining areas where diglossia still existed, it began to collapse in favour of the lower language, rather than Ziba, or it was that a colonial language replaced Ziba as the high language.

However, Ziba did remain in use, and was even preferred by colonial authorities at times, as an easily accessible and established language of administration. It also continued to be used as the native language in areas where it was established as such.

The dissolution of the Aguda Empire also saw increased divergence in the dialects of Ziba, some of which approached mutual unintelligibility, or which even were replaced by contact languages in marginal regions. Notably, trade pidgins on Lake Zindarud crystallised into Dameda, a Ziba-based creole.

The phenomenon of gowsas (indentured labour being sent to Euclean colonies in the Asterias and elsewhere), meanwhile, saw the emergence of Asterian Ziba dialects, including notably Carucerean Ziba. Ziba was a particular influence also on Papotement, the main language of Carucere. Gowsas, drawn from across the Aguda Empire's territories or ex-territories, often found that Ziba was the only language they shared, and levelled to it even if it was not their native language, replicating a similar dynamic to that of the koiné Agudan Ziba.

Over time, many loanwords entered Ziba from colonial languages, principally Estmerish and Gaullican, but also from Solarian, as classicisms, and also some other languages such as Soravian, Weranian and Amathian. Many of these words were to do with the new ideas and things introduced by Euclean colonialism, ranging from political ideologies to industrial equipment to Solarian law concepts to Euclean culture. Many loanwords fell out of usage or were condemned after decolonisation.

The late colonial period, as a result of the advent of newspapers, telegraphs, railways, printing presses, public schools, industrial urbanisation and so on, saw a proliferation in the amount and availability of written material. Some nascent political movements, including socialist, nationalist and pro-independence, promoted the use of Ziba at this time, contributing to a renaissance. These developments were repressed to an extent by colonial authorities, particularly the national functionalist Gaullican regime through the Bureau for Southeast Coius.

Some proposals were made for Ziba to be written in the Solarian alphabet, supposedly to improve literacy and increase links with Euclea. As the existing writing system was sufficient and simple, these proposals generally did not take off, though they formed the basis for the Conventional Transliteration which has become virtually universally used for transliterating Ziba into the Solarian alphabet. Carucerean Ziba, notably, is written in the Solarian alphabet.

Modern

With the independence of Dezevau, Ziba became the official language of a nation-state, with recognition following in Lavana, Hacyinia and Carucere.

The partition of Southeast Coius, which delineated Dezevau and Lavana from the Estmerish Community of Nations mandate over ex-Gaullican Southeast Coius, resulted in mass migration and communal disorder. Many people who considered themselves Dezevauni or who spoke Ziba (or both) were in the territory partitioned to Lavana, which was largely an ethnically Kachai state. Some Dezevaunis sought to reestablish a polity as expansive as the Aguda Empire had been, and there was a widespread expectation or fear of war breaking out between the two new states. In this context, the use of the Ziba language took on political implications. On the one hand, Dezevauni nationalists held it up as an ethnic language; some Ziba speakers switched to Kachai or other languages in the public sphere to avoid association with them in Lavana, either because they sympathised with the new state or feared reprisals. On the other hand, socialist Dezevau's promotion of Ziba was not very zealous, such that in Dezevau itself, speakers of minority languages saw the state as an ally against hardline Dezevauni nationalists, but nonetheless found the public use of Ziba unavoidable.

Lavana came to promote the Dhavoni identity in an attempt to cleave Ziba speakers in Lavana from identifying ethnically with Dezevaunis. War never broke out, the threat of it fading away as a result of socialist revolution in Lavana, and subsequent strong relations between Dezevau and Lavana. After being interrupted by the partition and the tense period thereafter, a cross-border language area exists again as a result of the Brown Sea Community. Nonetheless, there have been growing divergences between Ziba in Lavana and Dezevau, which have converged towards national varieties, though there is some evidence of further convergence to a common Brown Sea Community variety.

In the post-colonial period, while new loanwords entered from other languages, some were suppressed by national regulators, especially those from former colonisers, in an attempt to promote linguistic purity.

In Carucere, also, independence saw the possibility of recognition of non-colonial languages, such as Ziba. Carucerean Ziba was recognised, and established as being written in the Solarian alphabet, unusually.

The introduction of compulsory education, mass industrialisation and urbanisation, the development of computers and especially the Internet have seen a massive increase in literacy among Ziba speakers, as well as a massive increase in the written material in the language. By the 1990s, Ziba was part of most computer typographic encoding systems.

Ziba, because of the relative populousness, wealth and influence of the countries and populations using it in the middle Coian region, has continued to gain ground relative to other languages. In the context of a few languages displacing all others amidst globalisation, Ziba has been acclaimed as a "killer language", having displaced and continuing to displace neighbouring smaller languages. Fields in which Ziba takes precedence in its region include academia, diplomacy and the Internet.

Harmonisation

A novel policy of "harmonisation" was pursued in Dezevau, in response to the variety of (sometimes mutually unintelligible) dialects that existed in the country at independence in 1935. Conventional standardisation was viewed as politically undesirable or unviable, considering the strong tradition of politically or culturally distinct cities or states. The Ziba Harmonisation Agency was established to circumscribe and slowly converge the different dialects, while not prescribing a single acceptable standard where they differed. Though a Dezevauni agency, it also worked with the Brown Sea Community, and the Institute for Social Linguistics.

The policy of harmonisation is no longer as actively pursued, having been largely achieved its aims, though it remains in place at law. It is debatable, however, to what extent the policy had an effect, as opposed to convergence occurring naturally as development in communications and migration occurred across Dezevau. It has, however, had an impact on what is perceived as the "authentic" version of certain dialects. Some contend that harmonisation is in and of itself self-contradictory, and that it was simply a policy of standardisation, either to one standard or a handful of them, by stealth.

Geographic distribution

The areas where Ziba is natively spoken are mostly in Dezevau (excluding some southeastern regions which speak Pelangi, and some northwestern regions which speak Kexri), and the north of Lavana. Most of the language's 200 million or so native speakers reside in these regions; it is the most natively spoken language in Dezevau, and second in Lavana. However, millions of Ziba speakers are in neighbouring or diasporic populations, including in the rest of Lavana and in South Kabu which, together with Dezevau, comprise the Brown Sea Community. Notable populations of Ziba speakers also exist in border regions of Hacyinia (where they have legal recognition), Mabifia, and possibly Rwizikuru and Zorasan.

As a result of gowsa migration, many Ziba speakers exist throughout the Asterias and on Vehemens Ocean islands, especially in the tropics; notably, they have a particular presence and recognition in Carucere, in the Arucian (as Carucerean Ziba). A minority speak Ziba, in Aucuria, in Eldmark, on Kingsport, in Nuvania and in Vinalia. Diasporic Ziba-speaking populations, the result of direct migration or remigration of gowsas or their descendants, exist in Estmere and Gaullica, former colonisers of most of Ziba-speaking Southeast Coius. Additionally, a recognised Dezevauni minority exists in Amathia, as a result of guest worker migration during the Amathian Equalist Republic, with some still speaking Ziba; the same phenomenon exists to a lesser extent with Champania. It should be noted, however, that diasporic populations, especially after a few generations, do not retain their homeland's language; only a fraction of the large Dezevauni diaspora speaks Ziba.

Ziba is taught as an additional language across the Brown Sea Community, which utilises it as a working language, and in the countries with links to it nearby. It uncommon but not unknown for it to be taught in schools worldwide, with instances in Hennehouwe and Shangea.

Official status

Ziba is the sole official language at the federal level in Dezevau, and an official language in all of its states, either solely or in conjunction with other languages. In Dezevau, the federal Ziba Harmonisation Agency is the effective language regulator, though its function is somewhat unusual; rather than promulgating a standard variety, it works to bring different varieties closer to each other, and promotes "Harmonised Ziba", within which dialects may have circumscribed allowable variation.

Ziba is a national language in Lavana, though it is only natively spoken by a minority. It shares this legal status with Gaullican, Kachai, Majgars and Ukilen.

In Hacyinia, Ziba is one of five recognised regional languages, with Pardarian and Gaullican having recognised national status. Ziba is also recognised in the unrecognised state of the Yoloten, whose territory is internationally recognised as part of Hacyinia.

In Dezevau, Lavana and Hacyinia, the standardised varieties most resemble Southwestern Ziba (though they differ), because of its centrality and closeness to the historically prestigious Agudan Ziba.

Carucerean Ziba is a recognised language in Carucere.

Dialects

There are a number of different ways of categorising Ziba into dialects, though it can generally be recognised that there is a continuum of dialects from northeastern Dezevau to northern Lavana. Mutual intelligibility may require a degree of dialect levelling on the part of speakers from different ends of the continuum; there are differences phonetically, morphologically, lexically, and more broadly. In the past, dialects were associated with each city-state in Dezevau, but the mobility owing to the Aguda Empire, the Brown Sea Community, urbanisation, etc. mean that boundaries between dialects are even blurrier.

Generally, Southern, Western and Eastern groupings are recognised.

Southwestern Ziba/Agudan Ziba is the most prestigious, generally speaking, but Central Ziba is close in Dezevau.

One system of categorisation is:

- Central

- Bugunho

- Buiganhingi (or Low Buiganhingi)

- Mangime (or Dingi; sometimes incorrectly Pelangi Ziba)

- Vadidodhe (sometimes considered to be part of Eastern group)

- Zibiangego-Viododhe (controversial)

- Domoni?

- Eastern (sometimes collectively referred to as Doboadane)

- Asterian/Carucerean (sometimes categorised under Doboadane)

- Bouvai (sometimes imprecisely called Bougediame)

- Doboadane

- Dovoba

- Gigiduange (sometimes imprecisely called Gagaga)

- Southern/Southwestern

- Agudan (archaic)

- Dhavoni (controversial, novel, sometimes a subdialect of Zedenge)

- Gezije

- Gobobudi

- Zedenge

- Zigiava

- Western/Northwestern

- Lakeside/Zindarud

- Mhuogezu (or Mhuodhe Gebui, or Mhuodhe Gebui Zubomha)

- Noavanau (or Middle Buiganhingi)

Related languages

There are no extant Zibaic languages other than Ziba and its descendants. It is likely that the last of the other Zibaic languages went extinct during Ziba's medieval expansion, leaving only fragmentary evidence of their existence.

Dameda is an endangered Ziba-based creole (though some assert it was only a pidgin) which was mainly used as a common language for trade and travel on Lake Zindarud in the early modern period. Its Ziba influence is mainly from Western varieties.

Gavuba is a cant or sociolect which originated in the region around the Bay of Lights during the Aguda Empire, used by certain social classes of low prestige, including thieves, beggars, bandits, refugees, criminals, classless people, foreign sex workers and the chronically unemployed. It was used as a code for getting around Gaullican surveillance and intelligence in the late colonial period, and is today nearly extinct. It has had some lexical influences on modern Ziba.

Papotement is a creole spoken on Carucere which has influences from Ziba (mainly Carucerean), as a result of gowsa migration; a number of other Arucian creoles exhibit similar influence, albeit to a lesser degree.

Phonology

Consonants

Ziba has twelve consonants, being not altogether dissimilar in size or selection to some of the Vehemenic languages which Ziba is a neighbour to (such as Kabuese or Pelangi). There are, however, some cross-linguistically unusual features, namely: that all the consonants are voiced, or that there is no voicing distinction; that cross-linguistically common voiced consonants such as the voiced alveolar lateral approximant ([l]) or the voiced labial–velar approximant ([w]), and that there is a distinction between a sibilant and non-sibilant fricative (such a distinction is only recognised in one other official language: Frellandic, in Scovern).

The "regular" articulatory distribution of Ziba consonants may be regarded as a form of systematic phonemic differentiation, though it may also have been influenced by intentional prescriptive language planning in the Aguda Empire. The collapsing of voicing may also be a relatively recent and related feature. It should be noted that the phonology as here described is according to standard varieties in Dezevau, and considerable shifts are seen in some dialects.

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | ɱ | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Stop | b | b̪ | d | ɟ | g | |

| Fricative | sibilant | z | ||||

| non-sibilant | ð̠ | |||||

Vowels

For monophthongs, Ziba has a fairly straightforward five vowel system. Notably, however, it lacks rounded vowels in most dialects.

Ziba has diphthongs, which occupy the same phonotactic position as monophthongs. A diphthong can be formed from any two monophthongs other than the mid central vowel (ə). This formula means there are twelve possible diphthongs.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɯ | |

| Mid | ə | ||

| Open | a | ɒ |

Phonotactics

Ziba prescribes a syllable structure of CV (one consonant, one vowel). This somewhat unusual strictness can be a cause of difficulty when transcribing into Ziba from other languages; the mid central vowel is used to separate consonant clusters.

The abugida or abugida-like and cursive Ziba script corresponds to the phonotactics, inasmuch as there is no usual way to write consonant clusters, consonantless vowels or triphthongs.

In part because of Ziba's agglutinating character, there are few special phonological features which occur at word (or even sentence) boundaries (Sandhi) that do not occur at syllable boundaries.

Grammar

Ziba is an agglutinating language, with relatively simple syntax around verbs and extensive noun/adjective morphology, including suffixes which can be analysed as postpositions. It is generally copula-dropping, and makes use of subject-verb-object order to structure sentences. Ziba's grammar is widely considered to be relatively simple, and easy to learn, characteristic of its historical development as a widespread contact language—it has been compared to Estmerish in this regard.

Noun and adjective morphology

A high degree of noun/adjective compounding/affixation is characteristic of Ziba. Adjectives or modifying nouns precede the head in Ziba; complex concepts are commonly expressed in Ziba by rolling them into a noun phrase, which can include relative clauses.

For instance, an old statue, pointing north, inside a circle, made of sandstone, would be baidhediu-goaboazia-zuanibibo-nhuago-zabua (dashes inserted for clarity), literally "north-pointing, circle-inside, sandstone-made of, old statue".

There is room for ambiguity in the ordering of different parts of a noun phrase; for example, in the previous example, baidhediu goaboazia could potentially mean that the circle is pointing north, rather than the statue. Inference suggests that it is the statue pointing north, rather than the circle, inasmuch as it is less clear what it means for a circle to point in a direction. Generally, the more semantically intrinsic a modifier, the closer it is to the head; nhuago ("old") in the example is adjacent to zabua ("statue"); if it had been placed before goaboa ("circle"), for example, this would suggest an intent for the circle to be old, rather than the statue. Usually, unaffixed adjectives are taken to be more intrinsic than constructions using adjective-forming suffixes.

A number of morphemes are generally only used as noun-forming suffixes, but such morphemes are not actually ungrammatical when standing on their own. Adjective-forming suffixes (also analysed as postpositions), on the other hand, may be grammatically dependent on having an antecedent. For example, given zuanibibo, zuanibi is the noun meaning sandstone and bo is an adjective-forming suffix meaning made thereof; hence, zuanibibo is an adjective meaning "made of sandstone". There are many highly productive adjective-forming suffixes, and all nouns are also grammatically capable of affixation. Adjective-forming suffixes are generally a closed class.

Whether a given construction is a word or a phrase is a matter of controversy in analysis; it is normal therefore to refer to noun phrases and adjectival phrases, rather than words, in Ziba syntax (comparable to the Shangean distinction between 单词 and 字). It is, however, the most common practice to refer to noun or adjective phrases with no subordinate phrases as words. In contemporary Ziba, it is common practice to place spaces between such phrases, similar to the contemporary writing of Euclean or Vehemenic languages.

Pronouns

Pronouns are not a distinct word class in Ziba grammatically, but rather behave as normal nouns, despite their semantic deixis. They can have adjectives applied to them, have derivational suffixes applied in the regular way (e.g. when forming the possessive), be pluralised in the regular way, and maintain their form regardless of where in the sentence they occur. In this respect, they are similar to pronouns in Senrian.

Number and plurals

Ziba's indefinite plural, uniquely for the language, is formed by duplicating the first syllable of a noun at the end of the word; for instance, juigami, "fruit tree", becomes juigamijui, "fruit trees". This form is used where the intention is to convey that the noun is actually plural, but not where the intent is to refer to the noun generally (e.g. in Estmerish, this plural would be used to translate "cows" in "I saw cows in the paddock", but not in "Cows eat grass"). Where a noun phrase is plural, generally only the head morpheme is used for reduplication (as opposed to attached adjectival morphemes), but reduplication from a larger chunk may occur if the word is very well established. Some words are not pluralised, or regarded as inherently plural, because of their characteristics (often, uncountable nouns, such as water).

Apart from this formation, there are a number of adjectives which indicate number, as well as numerals themselves which can also be used as adjectives. The non-numeral adjectives which are in common use for indicating number include bebu, meaning "a few" or "not many", zibu, meaning "some", and dhebu, meaning "many". The word for the number twenty, deze, can also be used as a pluralising term beyond just the number twenty, to mean "innumerably many" or "all", in a plenary sense. Notably, the name Dezevau makes use of this, properly meaning "many lands" rather than "twenty lands".

If a number word (either a specific numeral or an alternative pluraliser), then the partial-reduplication indefinite plural construction is not used; they are grammatically mutually exclusive.

Verbs

Verbs do not morphosyntactically align in Ziba; subjects and objects are characterised by being before and after the verb, respectively. Verbs are modified by adverbs or adverbial phrases, which, like adjectives in relation to nouns, come before the verbs. Adverbial constructions, however, are generally simpler than noun phrases in Ziba. Tense, aspect, manner, and so on are all handled through the open content class of adverbs. They are only specified, however, when relevant, with the present tense and progressive (or continuous, depending on the word) aspect being assumed by default. Number, voice and so forth are not specified, being functions of the sentence or the subject or object.

An caveat to the system of adverbs is when the mood of the verb changes (by default, it is realis). Imperatives are formed by the suffix ze, and participles (nouns or adjectives formed from verbs, non-finite verbs) are formed using other suffixes (which may also be used to form non-participle adjectives and nouns). Adverbs can still be applied as normal to participles or imperative verbs.

The greatest number of verbs inherently require both subjects and objects (and may semantically but not grammatically require indirect objects, as adverbs or using the da-suffix construction); they may be regarded as transitive. However, there are also many ambitransitive and intransitive verbs, for whom objects are optional or impossible, as well as verbs which cannot or may not take subjects (and which may also have a requirement, option or aversion for objects). Confusion can arise where there is elision of parts of a sentence which does not affect the underlying grammatical properties of the verb (an Estmerish example of the phenomenon would be where "I" is elided from "Did you go today?" "Didn't go today.")

Adverbs

Adverbs are a distinct class from adjectives, but some words are both, particularly intensifiers. Adverbs can be formed by suffixation from other classes (though the variety and depth of suffixes is less than for adjectives), but in recent times the number of "flat" adverbs/adjectives, with zero-derivation from one to the other, has increased. -jiu is a standard adverb-forming suffix for adjectives. In these verb-related features, Ziba has been particularly influential on Papotement.

Copula

Ziba is normally copula-dropping where the predicate is a noun phrase, but there is a default copulative verb, dua, and some others with more specific meanings. For adjectival predicates, the suffix gai is attached to its end, and it is moved to the start of the sentence, rather than having a copula verb. However, some analyse the suffix as a verb, as it still occupies the medial place between the subject and the predicate (if in reverse).

Sentence structure

The default sentence structure in Ziba is subject-verb-object, with word order distinguishing the components. Subject-verb and verb-object constructions are allowed, either eliding the subject or object, or where the verb does not need to take a subject or object (i.e. being permissively intransitive or inherently passive). Despite this possibility, Ziba does not drop pronouns enough to be regarded as a pro-drop language.

In sentences composed of a subject and a subject complement, where the complement is a noun phrase, the copula may be omitted, but the verb dua may be used, for emphasis or to provide a point to attach adverbs to, and so on. Where there is an adjectival complement, the usual construction is to place the complement at the beginning, and suffix the phrase with gai, and then have the subject.

Coordination and subordination

Conjunctions can flexibly compound independent clauses, phrases, or two out of three parts in an SVO sentence at a time; for instance, they may permit such structures as (S)C(S)VO, S(VO)C(VO), S(V)C(V)O, (SVO)C(SVO) or (SV)C(SV)(O)C(O). There are a few different conjunctions with different grammatical functions, as well as different semantic meanings. What components of a sentence a conjunction applies to depends both on the conjunction itself, and what is permissible with the components of the sentence; for instance, in a sentence SVCVO, the conjunction will not be taken as applying both verbs to the object if the first verb is intransitive by nature (i.e. does not take objects).

Indirect objects are included in a sentence generally as an adverbial phrase preceding the verb, with an appropriate adverbial suffix. However, an alternative construction, which until recently was regarded as informal (despite widespread use), is to place the indirect object at the end, preceded by the conjunction da. The identity of the phrase as an indirect object is conveyed both by the conjunction and its position in this way; the sentence can be analysed as SV(O)C(O).

Relative clauses are created by placing the suffix na after a clause; na approximately translates to "that", or a sentence suffixed with it could be roughly translated to "the fact that <sentence>". For example, mhua zudho ni zebiu na (literally god-desire-people-move-that) can be translated as "The god desires that the people move."

Vocabulary

Ziba has a large number of independent morphemes, or words, with most being nouns or adjectives, fewer being verbs and adverbs, and fewest of all being conjunctions and interjections. There is also a number of derivational suffixes.

Ziba, as a widely spoken and well-documented language, has a larger lexis than many other languages. Official dictionaries include the Complete Harmonised Ziba Dictionary, produced by the Ziba Harmonisation Agency of Dezevau (last updated in 2019).

Word formation processes other than loaning are mostly to do with agglutination; new independent morphemes are only relatively rarely created. Initialism is an important process for creating those. Onomatopoeia and creation ab nihilo are not unknown, however.

Genealogical origin

Most words are of Zibaic origin, and are recognisable in Middle Ziba. Many can be traced back to Old Ziba, albeit to the extent that the language is fragmentarily documented and not wholly reconstructed.

A substantial number of words, however, are loanwords, in a few specific lexical fields or dialects. For instance, there are many Estmerish and Gaullican loanwords in computer science, and many Pelangi loanwords in dialects spoken in southeastern Dezevau. Many loanwords entered the language during colonisation, in the 19th and 20th centuries, but were subsequently suppressed upon independence. For instance, medi, from Gaullican métis ("mixed"), is only used in Asterian Ziba to mean mixed ethnicity. A second wave of loanwords has entered Ziba, with the advent of globalisation and the Information Revolution, which has not seen as negative a reaction from linguistic regulators.

Lexical substrates can be detected in Ziba as a result of it historically being the high language in diglossic situations; where Ziba became established as a native language, it absorbed words from the low languages with regards to certain aspects of domestic life, or other fields of low prestige, such as slang. Both Zibaic and non-Zibaic languages may have been contributed to substrates. The dialect-specificity of the substrates has decayed over time, as Ziba has changed and converged as a language.

Ziba has, in turn, contributed many loanwords to other languages, both its immediate neighbours and in the world more broadly. Many are in cultural, agricultural, scientific or religious lexical fields.

Initialisms

Especially for proper nouns, long technical terms and in slang, Ziba may initialise a phrase or longer construction by taking the first syllable of each word (possibly excluding conjunctions, and sometimes including important suffixes). The words produced by this process are generally regarded as words in and of themselves, and not analysable; for instance, the name of the Aguda Empire city of Gomheba (present-day Zuvai), was shortened from gomomongai mhenhe badha ju (bowing-hopeful-just-city). If it were to be pluralised, its plural would be gomhebago. Note the complete omission of ju, meaning city, which is conventional in this context because it is implied.

Metaphors

All languages use metaphors to express some abstract concepts such as time, morality, value and so forth; Ziba is no different.

In Ziba, unlike Euclean languages, up is not necessarily associated with goodness or purity (consider in Estmerish "higher power" or "base desires"). Historically, the opposite with true, with gravity being interpreted as meaning that the fundament of reality was (and therefore the gods were) downwards. However, perhaps related to Euclean influence and increased irreligiosity, this is no longer consistently interpreted.

The use of the direction metaphor for time, meanwhile, has largely been absorbed from Euclean languages into Ziba; the passage of time is conceived of as moving "forwards", and going into the past as "backwards".

Other metaphors are also important.

Writing system

Ziba's twelve consonants and five vowels are represented in the Ziba script with the consonants forming the bulk of a syllabic character, and the vowel being a smaller but essential part. The smallest orthographic unit in Ziba is therefore a syllable of CV. Ziba is generally considered an abugida, with the mid central vowel being the default vowel, but inasmuch as the joining line which otherwise exists in the vowel's spot can never mean anything other than the mid central vowel, Ziba could also be taken as an alphabet that just writes its vowels less prominently.

Diphthongs are represented by reducing the height of the vowel graphemes involved, modifying them slightly in some cases, and placing one to the top left, and the other to the bottom right. This increases the width of the whole syllable in writing.

Ziba script as it is presently recognised largely emerged out of the Aguda Empire era reforms. As it was intended for at that time, it still has a very close correspondence between graphemes and phonemes. As a result, it is relatively easy to learn and use. Archaic letters or pictographs (used until the medieval period) are used only stylistically and occasionally. Where there is a need to distinguish between contemporary Ziba script and archaic forms, generally the contemporary is referred to as Agudan Ziba Script.

Ziba "alphabetical" order goes /m/, /ɱ/, /n/, /ɲ/, /ŋ/, /b/, /b̪/, /d/, /ɟ, /g/, /ð̠/, /z/ for the consonants (moving front-to-back in the mouth through all five nasals then all five stops, for the first ten) and /ə/, /a/, /ɒ/, /i/, /ɯ/ for the vowels.

The most commonly used group of typefaces in printing and online are called vengai, based on the straight lines and angles of standard typeset printing from the Aguda Empire onwards. In handwriting, cursive is usual, and is taught in schools; it makes much more use of rounded loops and shapes that carry through between the consonantal and vowel parts of syllables. Some typefaces resemble cursive entirely and are known as jaujejua ("riverlike") or simply as cursive face, while use some cursive corners and rounded shapes while keeping an overall figure similar to vengai (sometimes in pursuit of better readability); these are called goaboajua, meaning circle-like. Virtually all Ziba writing is fully joined (at the starting and ending points of syllables, at the bottom), another practice that became standard in the Aguda Empire. Omitting horizontals at the beginning of an unjoined segment is a practice which relates to emphasising joined and unjoined sections of text. Doing the same at the end of unjoined segments is less commonly done, but similar in nature.

Though Ziba is formally composed of graphemically independent consonants and vowels (though they are physically joined), studies have been done to see if readers read the whole syllable at once, or in parts. Generally, readers recognise the entire syllable, rather than reading its components, even though they are perfectly capable of recognising the components. It is believed that because of the relatively small number of possible syllable combinations (around a hundred), this practice speeds up reading comprehension. Studies about graph-phone association, however, cannot be generalised to reading of semantic units such as words.

Transliteration

A variety of unsystematic practices were used for the transcription and transliteration of Ziba right up until the 19th or 20th centuries; words such as gowsa (gauza in Conventional Transliteration) were borrowed from Ziba at this time. Transcription was complicated by the various varieties in use, including Agudan Ziba as it was spoken in court, and Doboadane varieties in the most commercially Euclean-dominated region.

A number of systems were devised in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for transliterating Ziba into various Euclean languages, as the scope of Euclean scholarship expanded. Owing to Ziba's relatively simple phonology and graphic-phonetic correspondence, the various systems of transliteration broadly usable, and varied mainly only stylistically, or according to what language or dialect they aimed to resemble or transliterate from. Proposals were made to standardise the systems, perhaps with a view to making Solarianised Ziba official in place of the Ziba script, but they suffered from rivalry between Gaullican and Estmerish-style transliterations.

One of the first acts of the newly independent Republic of Dezevau was to establish that the Ziba script would continue to be used for Ziba, but also to approve an official transliteration for use in most Euclean languages, which became known as Conventional Transliteration. This was mainly a levelling of the consensus among Estmerish systems, preferencing them over Gaullican ones, inasmuch as the government wanted to distance itself from Gaullican cultural assimilative efforts. Conventional Transliteration quickly became established around the world as the standard, also gaining the backing of other states which used Ziba.

Transliteration into Ziba is less systematic, depending greatly on the language being transliterated from and the exact pronunciation; this is in part due to Ziba's limited phonological inventory and strict phonotactical rules. Some generally applied rules can be observed, such as that the mid central vowel is used to separate consonant clusters, the alveolar stop to replace alveolar lateral approximants, and the non-sibilant fricative rhotics.

Sample text

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

See also

Bibliography

- Gejeji Zaguazu and Anna Dize. 1988. "A Broad Geography of Ziba Dialectology". Journal of Applied Linguistics 11(3). 56.

- Ziba Harmonisation Agency of Dezevau. 2019. Complete Harmonised Ziba Dictionary (2019). Government of Dezevau Press. <https://ziba.org/>.