User:Finium/Sandbox

Ghobhapra was a system of reciprocal risk management that helped to maintain Trans-Coian trade across the Shalegho Mountains and the Dasht-e-Aftab. It developed from a system of livestock management that allowed tribal groups and caravan owners to cooperate. It has also been called the "Guild of the Beasts," though this has gone out of style. In the modern day, Ghobhapra persists as a kind of contract between self-managed labor groups and capital organizations or individuals. It exists in contrast to Sattari's "union of animal needs" and the Nationalist Principalists concept of socialism, though they all share some ideological heritage.

Etymology

The term Ghobhapra descends from the Phuli phrase "ghoda-vyapariko pratijna", which forms the syllabic abbreviation Gho-Vya-Pra and has been corrupted to its current form. Ghoda-vyapariko pratijna means "horse-seller's promise" which was used mostly a pejorative phrase meaning that the speaker could not be trusted, or that they could only be trusted as far as their wares could be tested.

The merchants of Ghobhapra were called "Ghoditra" with the word "mitra" (friend) added, which now also used a term for the descendants of the original merchant families.

History

Origins

Since crossing the Shalegho Mountains was such an intensive and time sensitive endeavor, it both required a high quality of draft animal and also a substantial period of recovery for the animals. To facilitate the necessary rest period for horses and camels, merchants would sell their spent animals to local animal traders and buy or rent new animals to return home. The traders who were supposed to graze the animals until they recovered would sometimes attempt to sell or rent animals who had not recovered from their last journey to a new traders; typically they achieved this by slipping exhausted animals into groups of healthy animals. As the practice became more common, it began to impact the flow of goods as more and more animals would die in transit. To end the practice, merchants began demanding assurances from their supply chain.

A typical contract ensured the health of animal and its ability to carry a defined amount of weight for a specific number of miles. For example, a camel could carry one load of silk from Kumuso to Namrin. If the animal failed to reach its destination, the seller would be liable for the cost of the animal and for its cargo. Since the death of animals was very common along the mountain and desert routes of central Coius, sometimes entire caravans being swallowed by the harsh landscape, these contracts were extremely expensive. The cost of hiring a caravan became prohibitively high and only the wealthiest merchants and officials could afford the cost.

Some horse sellers formed Ghobhapra contracts for other activities. Grazing, which was initially their primary business, was also ensured in this way to defray the costs of drought and landslide. One man even wrote Ghobhapra for his seven daughters and required each man to pay an extra bride price in case any of them turned out not to be virgins, but that tale may be apocryphal.

Development

As trade routes between the north and south coasts of Coius became more reliable, there was a decline in the demand for Ghobhapra. More and more merchants operated their own herds, incorporating the risks into their own much larger portfolios. The Ghoditra, who by this time were only tangentially related to the rearing of draft animals, began to seek other investments. The acquired interests in plantations, mills, and even began to ship goods through their former merchant partners. Despite this change in portfolios, the Ghoditra did still offer sureties and assurances permeated their business relationships. The Ghoditra formed capital associations among themselves and established a web of inter-dependency that helped them to survive some of the economic troubles of industrialization. Because of their cooperation, many of their assets could not be freely sold and required some mutual agreement of other Ghoditra. This initially made them very resistant to Euclean Colonialism, but colonial powers tended to seize what they could not purchase, pushing the Ghoditra even further to the periphery of society.

The dispossession of the Ghoditra was most strongly felt in Southern Zorasan, where the Etrurians felt that the tradition of trade among the Ghoditra was a threat to their desired monopsony.

The remaining horses owned by the new Ghoditra were primarily instruments of leisure and sport. This new direction of breeding yielded the Gho-Gho Horse. Gho-Gho descends from the Phuli "Ghodako Ghoda", or "Horse's Horse", a jibe at the unsavory origins of Ghoditra wealth.

Modern

Ghoditra

Ghobhapra is occasionally still used as a synonym for insurance and there are even professionals who call themselves Ghoditra. The majority of people who identify themselves as Ghoditra, however, are the descendants of dispossessed families that have been diasporacized by the political and economic centralization of Zorasan and Xiaodong. In Zorasan, the Ghoditra were initially welcomed to the new, anti-colonial society as a part of the state's embrace of Pardaran culture. Sattari even visited the Ghoditra village of Dhakyara in 1945 during a tour of Samrin and wrote that the Ghoditra epitomized the kind of universal values that could fortify Pan-Zorsani culture, which earned the support of the Ghoditra minorities in Pardaran and Samrin. Later on, however, during the Normalisation of the Al-Hizan, the Ghoditra were compelled to conform to the Sattarist principle of collectivization. While not as violent as it was for tribal Badawiyans, it did force communities to abandon their traditional laws and ultimately a loss of ethnic identity. Under the Jahandar government, important figures within the Ghoditra community were politically rehabilitated and new, much smaller villages emerged.

In Xiaodong, the Ghoditra remain a suppressed ethnic group, both for their investment in the private society, for their adherence to Irfan, and their non-standard dialect. It is not technically illegal to form Ghobhapra communities, but none have been publicly formed even after the Orchid Revolution. Occasionally, Ghoditra political dissidents are expatriated to Kumuso or Zorasan.

Labor Theory

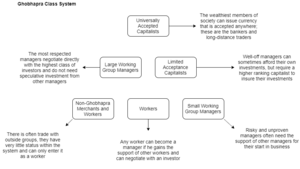

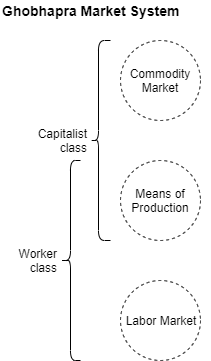

Ghobhapra as an economic system is the combination of self-managed labor groups with patronage from the capitalist class. Under this system, the labor group, which is similar to a union, is first established as a legal entity; all of the workers will pledge their work to the group. These groups will typically have a specific, complete service they can provide. Traditionally that service was husbandry, including farriery and shepherding. All people who performed work at a given location had to be included in the group including managers and support services, otherwise the contract was void and the workers had no responsibility to the organization. The group would then seek or be sought by an investor who would pay the group an annual amount to complete work for them for a set number of year. The investor also had to provide them with the necessary resources, in the traditional model, this meant the draft animals and/or the grazing land. Tools were purchased by and owned by the group.

In traditional society, there can be no movement between the capitalist and worker classes. Certain goods were also limited into the two spheres of exchange. Land could only be owned by the capitalists as well as gold. Every capitalist minted their own currency and was responsible for ensuring that other capitalists would accept their letters of credit.

Modernization has changed these limitations. It is now possible for the managers of worker groups or members of highly compensated worker groups to patronize other groups. For example, the manager of a herding operation might finance a neighboring farming operation. Because of the requirement of universal incorporation of labor, however, such a manager may not sell his own group goods from other groups. Such a manager must sell commodities to other capitalists who may then redistribute the goods to their own investments. Complexities like this are often seen as a threat to the traditional way of life, however, and so the upper class will often refuse to do business with manager-investments.

The capitalist class, because it must make payments in advance, absorbs all of the risks of these ventures. They depend on interpersonal relationships and mutual risk agreements to weather unfavorable events such as natural disasters and business cycles. If a member of the upper class takes too many risky ventures, they risk being ostracized, whereas managers who avert losses can sometimes be elevated to high status.