Sodality (Bahia)

Sodalities are initiatory societies, typically religious or otherwise spiritual, from Bahia. The term is used to designate any non-kinship based group which employs initiatory and secretive practices, has restricted membership, and a shared goal or mythos. Though often conflated with Bahian fetishism, sodalities are present in both Irfanic and Sotirian Bahia, and have been influential in the Bahian diaspora.

History

Origins

Secret societies were a feature of Bahian societies from at least the sare period, with diverse purviews. During the rise of hourege they came to oversee the division of society into occupation-based castes, as professions such as hunters and blacksmiths formed initiatory groups to preserve their skills and share in rituals.

Early modern period

From the 16th century new sodalities with increasing religious and political ambition emerged in the context of the Lourale ka Maoube. While they were mainly scholarly in nature, many also played a role in political intrigues, as they attempted to establish the supremacy of their religion and school of thought. The networks of sodalities allowed them to easily gain control of the machinery of Bahian government, and become the main selectorate for houregic rulers; Bahian politics became increasingly (or, in some views, returned to being) secretive and conspiratorial. Another kind of warrior sodality emerged in Dovoba under the Aguda Empire, which promoted extremely violent new religions and converged with the Louralic sodalities in terms of political ambition.

The Transvehemens slave trade and the turmoil of the Zombibudi Wars led to a further expansion of sodalities to protect members and facilitate trust in the wake of widespread institutional collapse.

Colonial period

Sodalities were mistrusted during the colonial era and many were targetted by colonial authorities, though this approach was varied and in some areas sodalities were seen as a means of ruling otherwise restive peoples. In Euclean culture of the time, such societies were typically viewed as barbaric, with their secretive practices leading to rumors of cannibalism and violence which were played upon in Roman austral literature.

Modern history

Following independence, the approaches of Bahian governments vis a vis sodalities has typically been repressive, with their status as alternative sources of governance seen as subversive. Sodalities are also present in the Asterias, having played a key role in preserving Bahian identity among the diaspora.

Classification

In her work La Case noire: Les Sodalités en Baïe, bahianologist Michelle Yseult divided the different sodalities of Bahia into three categories based on their membership criteria. While these categories are somewhat general, they help to generalise trends of sodality structure, role, and activity. Not all of these categories are universal, with generational sodalities in particular being rarer.

Professional

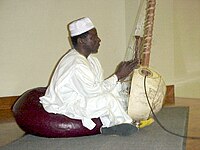

The most numerous and famous of the sodalities are professional sodalities, which Yseult defined as being initiatory societies formed around the basis of common occupation and a common, secretive mythos. These societies are typically held to be the oldest, and indeed many professional sodalities can be dated back well before the start of the transvehemens slave trade. One such example are the Djelis of the Boual ka Bifie, musicians who functioned as traditional retainers of knowledge. For the Djelis, who were a slave caste and therefore posessed by others, these sodalities provided support networks and interpersonal protections as well as protecting the skills of their craft. Initiation and mysticism therefore also helped to preserve the power and exclusivity of the Djelis, limiting the ability of others to imitate their craft. Similar themes can be seen with blacksmith and hunter sodalities particularly in coastal areas. In many areas, it was control of metalworking which guaranteed one state power as the metalworkers were the ones who crafted the fetishes which gave one spiritual authority. Yseult also included in this category sodalities centred around the slave trade, such as the Imamfu society of the Ingona coast which emerged in order to facilitate slave capturing and trading.

As their raison d'être is more strictly based on the profession which they gatekeep, professional sodalities have proven remarkably resiliant to changes in the religious environs they emerged from. The Djelis of the Boual ka Bifie, among many others, were able to survive the Irfanisation of the plains by changing their foundational mythos in a similar way to that of the Afomamirabe among Ndjarendie kinship groups. This is attested by several Sewa Djeli songs, which claim ancestry from the same initial group as several neighbouring Irfanic Djeli sodalities, yet tell vastly different versions of the myths. In other areas, these sodalities have provided areas where fetishist beliefs and customs have survived even among peoples who still profess to Irfan or Sotirianity, but who fear to abandon rituals lest the spirits of their craft take away their knowledge.

Religious

Generational

The rarest of Yseult's sodality typologies, generational sodalities are limited to people groups with relative social equality and age-based heirarchies such as those of the Lolemo people of the Central Green Belt. In these societies, where labour was divided on a basis of age as opposed to caste or professional choice, it was necessary to initiate groups of people progressively as they aged. This would typically take the form of age classes, with all children born between two dates grouped together and educated together, before being initiated by the elders of their gender after puberty. Generational societies would typically be segregated by gender, so as to avoid in-group relationships which could complicate ritual practices. Some communities only maintained sodalities for one gender, though many communities possessed and continue to maintain two. These sodalities were vehicles for propagating and maintaining mores and societal worldviews, helping maintain group unity.

Generational sodalities were heavily influenced by the Transvehemens slave trade and associated cultural influences during the Toubacterie. The wars and captive-taking that characterised the trade era meant that whole age groups were heavily affected, especially in societies where only certain ages fought. This meant that gaps in the transferral chain occurred in the most affected people groups, which pushed some sodalities to near extinction. This was preserved in a Angba oral history, which recites that

The elders were eaten by the forests, and the young were lost. The people forgot their roots, and still we toil

However, as the generational model spread the initiated beliefs across a wider group of people, many societies were able to preserve their sacred knowledge. With evangelisation, many of these societies saw the catechism process as being remniscent of their traditional generational model, leading some sodalities to emerge again as evangelical sotirian churches with a broader, pan-ethnic base. This is most notable of the World Redemption Bahian Mission Church, which is highly syncretic in its beliefs.

Political

This kind of sodality seems to have specifically emerged in early modern Bahia, primarily arising from kingships in relatively fetishist areas being usurped by either an existing sodality or some other association who then collectively confer themselves kingship, sometimes through novel interpretations of imitera. If a 'royal' sodality does not directly serve as a collective head of state, it may be politically ambitious, or even treat itself as a state beyond the purview of any other ruler. In the 17th century many religious sodalities also took on a political character culminating in the Zombibudi Wars. However, with the decline and dissolution of fetishist houragic entities from which political sodalities drew their identity, those that survived became more generic fraternities and their royal claims simply initiated symbolism.