Costa Bravo: Difference between revisions

Costa Bravo (talk | contribs) |

Costa Bravo (talk | contribs) (→Media) |

||

| (84 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

|ethnic_groups_year = 2019 | |ethnic_groups_year = 2019 | ||

|ethnic_groups_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with ethnic groups data)--> | |ethnic_groups_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with ethnic groups data)--> | ||

|religion = 33.1% {{wp|Liberation theology|Liberational Catholicism}}<br>20.8% Buddhism<br>13.0% Hinduism<br>10.4% Islam<br> | |religion = 33.1% {{wp|Liberation theology|Liberational Catholicism}}<br>20.8% Buddhism<br>13.0% Hinduism<br>10.4% Islam<br>9.9% Quakerism<br>7.6% Judaism<br>5.3% other | ||

|religion_year = 2019 | |religion_year = 2019 | ||

|religion_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with religion data)--> | |religion_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with religion data)--> | ||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

|population_estimate_rank = | |population_estimate_rank = | ||

|population_estimate_year = | |population_estimate_year = | ||

|population_census = 5, | |population_census = 5,051,977 (+900,000 resident aliens) | ||

|population_census_year = 2019 | |population_census_year = 2019 | ||

|population_density_km2 = 25 | |population_density_km2 = 25 | ||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

|population_density_rank = | |population_density_rank = | ||

|nummembers = <!--An alternative to population for micronation--> | |nummembers = <!--An alternative to population for micronation--> | ||

|GDP_PPP = | |GDP_PPP = ƒ80 trillion | ||

|GDP_PPP_rank = | |GDP_PPP_rank = | ||

|GDP_PPP_year = | |GDP_PPP_year = | ||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita = | |GDP_PPP_per_capita = ƒ548,210 | ||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = | |GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = | ||

|GDP_nominal = | |GDP_nominal = ƒ70 trillion | ||

|GDP_nominal_rank = | |GDP_nominal_rank = | ||

|GDP_nominal_year = | |GDP_nominal_year = | ||

|GDP_nominal_per_capita = | |GDP_nominal_per_capita = ƒ359,340 | ||

|GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = | |GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = | ||

|Gini = .13 | |Gini = .13 | ||

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

'''Costa Bravo''', officially the '''Free State of Costa Bravo''' or '''Estado Libre de Costa Bravo''', is a {{wp|Democratic confederalism|confederal democracy}} located on a chain of islands spanning the {{wp|South Atlantic}} and {{wp|Indian Ocean|Southern Indian Ocean}}. Costa Bravo was formerly a colonial subject of {{wp|Spain}} and {{wp|Great Britain}}. It declared independence from Britain in 1812. The current form of government dates to 1991 following a period of civil war. | '''Costa Bravo''', officially the '''Free State of Costa Bravo''' or '''Estado Libre de Costa Bravo''', is a {{wp|Democratic confederalism|confederal democracy}} located on a chain of islands spanning the {{wp|South Atlantic}} and {{wp|Indian Ocean|Southern Indian Ocean}}. Costa Bravo was formerly a colonial subject of {{wp|Spain}} and {{wp|Great Britain}}. It declared independence from Britain in 1812. The current form of government dates to 1991 following a period of civil war. | ||

Costa Bravo is governed from the | Costa Bravo is governed from the 'bottom-up'. Every community, ethnicity, culture, religious group, intellectual movement, and economic unit is autonomously organized as a political entity. All issues of daily life are decided on by the members of these organizations in consensus decision-making and direct democracy. Issues are put to the vote in an endless stream of {{wp|Referendum|referendums}}. This political apparatus is highly digital: votes are cast by citizens 'on the go' with their personal smart devices and computers. Political participation and voting are mandatory for all citizens. There is no head of state, but a 'Representative' may be provisionally appointed to conduct diplomacy on the people’s behalf (for example). | ||

There is no official language. Media and daily conversations are in code-switched {{wp|English}} and {{wp|Spanish}}. This vernacular is called a la brava, or {{wp|Spanglish|Bravo Spanglish}}. | There is no official language. Media and daily conversations are in code-switched {{wp|English}} and {{wp|Spanish}}. This vernacular is called a la brava, or {{wp|Spanglish|Bravo Spanglish}}. | ||

| Line 159: | Line 159: | ||

The history of Costa Bravo prior to European discovery of the islands is imprecise on account of scarce archaeological remains. Estimated dates of initial settlement range from 500 to 1200 CE, approximately coinciding with the arrival of the first {{wp|Austronesian}} peoples in {{wp|Madagascar}}. These settlers came from {{wp|Melanesia}} and {{wp|Micronesia}}. The population size and specific cultural identities of the settlers are not precisely known. Only fragmentary skeletal and material remains have been uncovered. It is believed that settlement lasted for a few generations before collapse. Disease, political strife, or climate events have been hypothesized as the cause. | The history of Costa Bravo prior to European discovery of the islands is imprecise on account of scarce archaeological remains. Estimated dates of initial settlement range from 500 to 1200 CE, approximately coinciding with the arrival of the first {{wp|Austronesian}} peoples in {{wp|Madagascar}}. These settlers came from {{wp|Melanesia}} and {{wp|Micronesia}}. The population size and specific cultural identities of the settlers are not precisely known. Only fragmentary skeletal and material remains have been uncovered. It is believed that settlement lasted for a few generations before collapse. Disease, political strife, or climate events have been hypothesized as the cause. | ||

The Austronesian settlers are best known as the creators of the Satan Stone or Piedra de Satanás, a 3 meter tall oblate ovoid monolith carved from a silicate mineral meteorite. The stone was unearthed by farmers in the southern part of the main island in 1852. It has been on display at the People's Museum since 1900. The manner of its construction, its provenance, and the meaning of the glyphs covering its surface are all unknown. The glyphs are rendered in {{wp|Boustrophedon|boustrophedonic}} text but resemble no other writing system in the world. None of the text is definitively understood. Some modern linguists argue it is not true writing but {{wp|proto-writing}}, or even a more limited mnemonic device for genealogy, choreography, navigation, astronomy, or agriculture. There is continuing debate as to whether the glyphs are essentially {{wp|logographic}} or {{wp|Syllabary|syllabic}}, though they appear to be compatible with neither a pure logography nor a pure syllabary. The study of these glyphs, and the purpose of the Satan Stone itself, remains contentious to this day. The perception of the monolith as an object of Satanic power led to it almost being destroyed on two separate occasions in the 18th and 19th centuries. | The Austronesian settlers are best known as the creators of the [[Satan Stone|Satan Stone or Piedra de Satanás]], a 3 meter tall oblate ovoid monolith carved from a silicate mineral meteorite. The stone was unearthed by farmers in the southern part of the main island in 1852. It has been on display at the People's Museum since 1900. The manner of its construction, its provenance, and the meaning of the glyphs covering its surface are all unknown. The glyphs are rendered in {{wp|Boustrophedon|boustrophedonic}} text but resemble no other writing system in the world. None of the text is definitively understood. Some modern linguists argue it is not true writing but {{wp|proto-writing}}, or even a more limited mnemonic device for genealogy, choreography, navigation, astronomy, or agriculture. There is continuing debate as to whether the glyphs are essentially {{wp|logographic}} or {{wp|Syllabary|syllabic}}, though they appear to be compatible with neither a pure logography nor a pure syllabary. The study of these glyphs, and the purpose of the Satan Stone itself, remains contentious to this day. The perception of the monolith as an object of Satanic power led to it almost being destroyed on two separate occasions in the 18th and 19th centuries. | ||

=== European colonization === | === European colonization === | ||

The islands were rediscovered on 1 April, 1522 by {{wp|Juan Sebastián Elcano}} and the crew of the ''{{wp|Victoria (ship)|Victoria}}'' who completed the first circumnavigation of the world. In late March of 1522, the ''Victoria'' encountered a cyclone in the South Indian Ocean, which sent the ship into waters far to the south of her intended route. The crew chanced upon the archipelago now known as Costa Bravo, and there sheltered and provisioned for food and water. They remained on the islands from 1 April to 4 April 1522. The Venetian scholar {{wp|Antonio Pigafetta}} wrote extensively of the wildlife and terrain of the islands. In his journal, Pigafetta christened the place ''Costa Brava'' and noted its approximate location. The ''Victoria'' arrived in Spain five months later. | The islands were rediscovered on 1 April, 1522 by {{wp|Juan Sebastián Elcano}} and the crew of the ''{{wp|Victoria (ship)|Victoria}}'' who completed the first circumnavigation of the world. In late March of 1522, the ''Victoria'' encountered a cyclone in the South Indian Ocean, which sent the ship into waters far to the south of her intended route. The crew chanced upon the archipelago now known as Costa Bravo, and there sheltered and provisioned for food and water. They remained on the islands from 1 April to 4 April 1522. The Venetian scholar {{wp|Antonio Pigafetta}} wrote extensively of the wildlife and terrain of the islands. In his journal, Pigafetta christened the place ''Costa Brava'' and noted its approximate location. The ''Victoria'' arrived in Spain five months later. | ||

[[File:Detail from a map of Ortelius - Magellan's ship Victoria.png|left|thumb|The ''Victoria'', the first European ship to land on what is today Costa Bravo]] | |||

Spain immediately laid claim to the islands, in contravention of the 1494 {{wp|Treaty of Tordesillas}} which made the islands ''de jure'' Portuguese possessions. There were several failed ventures to colonize Costa Brava beginning as early as 1523. Only one such venture was undertaken prior to 1580, in which a flotilla of ships sailed from Seville in 1535 but failed to locate the islands. | Spain immediately laid claim to the islands, in contravention of the 1494 {{wp|Treaty of Tordesillas}} which made the islands ''de jure'' Portuguese possessions. There were several failed ventures to colonize Costa Brava beginning as early as 1523. Only one such venture was undertaken prior to 1580, in which a flotilla of ships sailed from Seville in 1535 but failed to locate the islands. | ||

The {{wp|Iberian Union|union of the Portuguese and Spanish crowns}} in 1580 revived colonization efforts, still to the exclusion of Portuguese interests, and a colonizing expedition landed on Costa Brava on 8 December, 1580. The colonists founded a small village on the east coast of the main island. This settlement was named Nuevo Puerto Hércules (after Port Hercules, Monaco) in honor of {{wp|Isabella Grimaldi}}, Lady of Monaco with whom the expedition leader Ignacio de Zárate was infatuated. Zárate had volunteered for the expedition to escape a death sentence for invading the Lady's bedchambers six months prior. A collection of love letters written by Zárate exhorting the Lady of Monaco to marry him and travel to Costa Brava—an impoverished, malarial backwater—are today on display in the People's Museum. | The {{wp|Iberian Union|union of the Portuguese and Spanish crowns}} in 1580 revived colonization efforts, still to the exclusion of Portuguese interests, and a colonizing expedition landed on Costa Brava on 8 December, 1580. The colonists founded a small village on the east coast of the main island. This settlement was named Nuevo Puerto Hércules (after Port Hercules, Monaco) in honor of {{wp|Isabella Grimaldi}}, Lady of Monaco with whom the expedition leader [[Ignacio de Zárate]] was infatuated. Zárate had volunteered for the expedition to escape a death sentence for invading the Lady's bedchambers six months prior. A collection of love letters written by Zárate exhorting the Lady of Monaco to marry him and travel to Costa Brava—an impoverished, malarial backwater—are today on display in the People's Museum. | ||

Costa Brava encompassed an administrative unit consisting of all of Spain's possessions in the South Atlantic and Southern Indian Ocean. Costa Brava itself was organized as a {{wp|captaincy}} and {{wp|Audiencia Real|audiencia}} of the {{wp|Viceroyalty of Peru}}. Although nominally no different than his peers, the {{wp|Captain General}} of Costa Brava had significant autonomy similar to the {{wp|Captaincy General of Santo Domingo|Captain General of Santo Domingo}}. | Costa Brava encompassed an administrative unit consisting of all of Spain's possessions in the South Atlantic and Southern Indian Ocean. Costa Brava itself was organized as a {{wp|captaincy}} and {{wp|Audiencia Real|audiencia}} of the {{wp|Viceroyalty of Peru}}. Although nominally no different than his peers, the {{wp|Captain General}} of Costa Brava had significant autonomy similar to the {{wp|Captaincy General of Santo Domingo|Captain General of Santo Domingo}}. | ||

[[File:Domenico Tintoretto - Portrait of a Man - WGA19637.jpg|thumb|right|Captain General and pirate Nicolás Benalcazar]] | |||

One of the most notable leaders of Costa Brava, Captain General Nicolás Benalcazar, is today celebrated as a picaresque Robin Hood-type folk hero. His privateer fleet in the 1610s commerce raided British {{wp|triangular trade}} ships. Benalcazar and his privateers were subject to censure from Spanish authorities considering the extralegal nature of Benalcazar's letters of marque. This caused a rift between Costa Brava and {{wp|Philip III of Spain|the Crown}}, ultimately leading to a strong culture of privateering on the islands that the viceregal government could do nothing to prevent. Benalcazar was stripped of office in 1617, after which he became a successful pirate. The {{wp|Golden Age of Piracy}} was a high watermark in the early cultural history of Costa Brava. Costa Brava became a byword of a place of debauchery and murder. The "Cold Caribbean" was a moniker frequently applied to the islands. Located at the southern apex of the {{wp|Pirate Round}}, Costa Brava was increasingly subject to the influences of cosmopolitan traders and pirates—and increasingly estranged from the Spanish metropole. | One of the most notable leaders of Costa Brava, Captain General [[Nicolás Benalcazar]], is today celebrated as a picaresque Robin Hood-type folk hero. His privateer fleet in the 1610s commerce raided British {{wp|triangular trade}} ships. Benalcazar and his privateers were subject to censure from Spanish authorities considering the extralegal nature of Benalcazar's letters of marque. This caused a rift between Costa Brava and {{wp|Philip III of Spain|the Crown}}, ultimately leading to a strong culture of privateering on the islands that the viceregal government could do nothing to prevent. Benalcazar was stripped of office in 1617, after which he became a successful pirate. The {{wp|Golden Age of Piracy}} was a high watermark in the early cultural history of Costa Brava. Costa Brava became a byword of a place of debauchery and murder. The "Cold Caribbean" was a moniker frequently applied to the islands. Located at the southern apex of the {{wp|Pirate Round}}, Costa Brava was increasingly subject to the influences of cosmopolitan traders and pirates—and increasingly estranged from the Spanish metropole. | ||

The {{wp|War of the Spanish Succession}} in the early 18th century was the first global conflict to directly involve Brava territories. Cognizant of a widening cultural gulf between the islands and mainland Europe, naval forces in Costa Brava mutinied rather than support the Spanish war effort. Costa Brava was chaotic in the early years of the war. The disorganized population of pirates attacked ports, ships, and each other across the South American, African, and Brava coasts. Nuevo Puerto Hércules exchanged hands between the Captain General and the independent factions three times before an expeditionary force of viceregal ships sufficiently put an end to the naval rebellion. From 1705 until the end of the war, Costa Brava experienced only intermittent pirate activity. | The {{wp|War of the Spanish Succession}} in the early 18th century was the first global conflict to directly involve Brava territories. Cognizant of a widening cultural gulf between the islands and mainland Europe, naval forces in Costa Brava mutinied rather than support the Spanish war effort. Costa Brava was chaotic in the early years of the war. The disorganized population of pirates attacked ports, ships, and each other across the South American, African, and Brava coasts. Nuevo Puerto Hércules exchanged hands between the Captain General and the independent factions three times before an expeditionary force of viceregal ships sufficiently put an end to the naval rebellion. From 1705 until the end of the war, Costa Brava experienced only intermittent pirate activity. | ||

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

Spain ceded Costa Brava to Great Britain as part of the {{wp|Peace of Utrecht}}. Costa Brava became the British Bravo Islands. | Spain ceded Costa Brava to Great Britain as part of the {{wp|Peace of Utrecht}}. Costa Brava became the British Bravo Islands. | ||

[[File:Cook-whaling.jpg|thumb|left|A Costa Brava whaling fishery]] | |||

Whaling came to predominate the economy under the British. During Spanish rule, whaling had been confined to marginal {{wp|History of Basque whaling|Basque}} communities on the islands. By 1800, Nuevo Puerto Hércules was regarded as the whaling capital of the world along with {{wp|Nantucket}}. The abundant {{wp|Minke whale|lesser rorqual}} was—and remains—a staple catch. Bravo whalers of this period were possibly the first people to make landfall on {{wp|Antarctica}}. Recent archaeological findings have uncovered whaling stations in the vicinity of {{wp|Prydz Bay}} which may date as early as c. 1750. | Whaling came to predominate the economy under the British. During Spanish rule, whaling had been confined to marginal {{wp|History of Basque whaling|Basque}} communities on the islands. By 1800, Nuevo Puerto Hércules was regarded as the whaling capital of the world along with {{wp|Nantucket}}. The abundant {{wp|Minke whale|lesser rorqual}} was—and remains—a staple catch. Bravo whalers of this period were possibly the first people to make landfall on {{wp|Antarctica}}. Recent archaeological findings have uncovered whaling stations in the vicinity of {{wp|Prydz Bay}} which may date as early as c. 1750. | ||

In March 1740, the British Bravo Islands were subject to the only land-based offensive by Spanish forces during the {{wp|War of Jenkins' Ear}}. A band of {{wp|porteño}} privateers from {{wp|Buenos Aires}} landed on Isla Roché y Las Últimas, seizing control of the islands. Porteño merchants and contrabandistas hoped to create an additional trade route outside of the closed port of Buenos Aires. The islands became a base of operations for Spanish privateers attacking the triangular trade route. By 1743, with the war subsumed by the {{wp|War of the Austrian Succession}}, locals in Hueco revolted and reclaimed the islands for the British. | In March 1740, the British Bravo Islands were subject to the only land-based offensive by Spanish forces during the {{wp|War of Jenkins' Ear}}. A band of {{wp|porteño}} privateers from {{wp|Buenos Aires}} landed on [[Isla Roché y Las Últimas]], seizing control of the islands. Porteño merchants and contrabandistas hoped to create an additional trade route outside of the closed port of Buenos Aires. The islands became a base of operations for Spanish privateers attacking the triangular trade route. By 1743, with the war subsumed by the {{wp|War of the Austrian Succession}}, locals in [[Hueco]] revolted and reclaimed the islands for the British. | ||

The remainder of the 18th century was peaceful and saw the total syncretization of Anglo and Hispanic culture. | The remainder of the 18th century was peaceful and saw the total syncretization of Anglo and Hispanic culture. | ||

[[File:Genova-1810ca-acquatinta-Garneray.jpg|right|thumb|Nuevo Puerto Hércules in 1801.]] | |||

British relations with their Bravo subjects soured following the outbreak of the {{wp|Napoleonic Wars}} in 1803. To sustain manpower for the war effort, the British Royal Navy relied heavily on {{wp|impressment}} from two main sources, American and Bravo sailors. Both populations had large numbers of career sailors and commercial fleets. Between 1806 and 1812, 6,000 American seamen and an estimated 20,000 Bravo seamen were impressed and taken against their will into the Royal Navy. | |||

Bravo women comprised over half of local whalers during this period, as there was a shortage of men remaining to do the work. Bravo whaler [[Leonora Toro]] retaliated against the British Navy by disguising herself and her crew as men and killing any officers who tried to pressgang them. In her most famous naval action dubbed the ''Fuego'' affair, she destroyed the HMS ''Spitcock'' with a fire ship, killing 20 British sailors. Leonora Toro was arrested in 1811 and executed along with 8 other women who participated in the affair (the remaining 20 crewmembers successfully {{wp|Pleading the belly|pled the belly}}). Impressment subsequently doubled; even some women sailors were pressganged along with the men. | |||

Bravo women | By 1812, sentiment in the British Bravo Islands had reached a critical low point. On 1 April, 1812, an uprising of women and young men stormed the Governor's Hall in Nuevo Puerto Hércules and presented a [[Bill of Redress|Bill of Redress or Carta de Reparación]] to Deputy Governor Gilbertine Rawls. Their demands were plainly refused. Scattered fighting erupted across the British Bravo Islands. Judging correctly that British forces were stretched too thin to suppress an uprising in the most remote settlement in the world, revolters unseated British authorities from power on every island within six months. The movement was originally a call for redress, not independence, but rapid gains shifted war goals. | ||

[[File:Delivery of the Bill of Redress.jpg|thumb|left|Delivery of the Bill of Redress on 1 April, 1812 in Nuevo Puerto Hércules]] | |||

A notable engagement was the [[Battle of Jauja]] in which 250 children attacked the British fort at [[Jauja]] and took captive the entire garrison. The islands of [[Zeda]] and [[Ye]] had been severely depopulated of working adults by impressment and the ongoing whaling season. Almost the entire revolutionary forces on the islands were below the age of majority. The children of Jauja enslaved the British soldiers and declared a [[Children's Republic]]. On 11 August, the army of the Children's Republic of Zeda launched an amphibious invasion of nearby British-controlled Ye. Fierce urban fighting in Dar es Coba lasted for three days and nights before the British surrendered. The Children's Republic of Zeda-Ye lasted until war's end, when it became a part of the newly formed Free Bravo Islands. | |||

In February of 1813 the Bravo forces (leaderless and almost two-thirds women) agreed to free 600 British captives in exchange for autonomy from British rule. The Bravo Revolution lasted 10 months. It left 800 Bravoes dead, 300 British dead, and 20 British ships sunk to Bravo 4. Some 4,000 people died from disease. When the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1814, many pressganged Bravoes finally returned home. | |||

=== The Free Bravo Islands (1812-1933) === | === The Free Bravo Islands (1812-1933) === | ||

A series of hasty, chaotic congresses were held in the aftermath of the peace agreement with the goal of determining the kind of government that should be formed. Important national-level congresses included the Congreso de Niños (Jauja), the Congreso Occidental-Central (Hueco), the Herculean Congress (Nuevo Puerto Hércules), and the Congreso de Mujeres y Viudas Afligadas (Zeta Fe). | |||

[[File:Congreso Mujeres.jpg|thumb|right|Constitutional debates at the Congreso de Mujeres y Viudas Afligadas in Zeta Fe, 1813]] | |||

The people established a {{wp|Directorial system|directory}} form of government and named it the Free Bravo Islands. Rather than a single executive, the government was headed by a five-member council of elected representatives. It was partially based on the {{wp|French Directory}} of 1795-1799. The Directory was invested with executive and legislative power; there was a separate judiciary headed by an elected Judge President or Presidente Juez. | |||

The first several decades of Free Bravo history were characterized by impoverished conditions and a struggle for self-sufficiency. A reliance on trade goods caused persistent food shortages as British ships raided Bravo commerce lanes. Modest trade in grain with the {{wp|United States of America}} and {{wp|France}} sustained the population in the face of agitation from the Capullist faction, a clique of liberal politicians who promoted reunification with Great Britain. The United States were the first to recognize Free Bravo sovereignty in 1817. France recognized Free Bravo in 1818, followed by the same from independent South American republics throughout the 1820s. | |||

The Famine of 1821 or Hambruna de los Comeflores caused inhabitants of hard-hit islands such as the Islas de la Cruz to eat flowers, bulbs, and seeds. | |||

Whaling became the sole healthy sector of Free Bravo's economy. A recent study has shown that two-thirds of the diet of Bravo citizens from 1813-1850 was whale. The Bravo government nationalized the whaling industry in 1818. A portion of the annual catch was exported, with the remaining surplus distributed evenly by Bravo navy ships to the people of the islands. The agricultural sector was mature enough in 1852 that whaling was denationalized and whale food programs ended. This period's effect on the culinary culture of Costa Bravo was immense. Most Costa Bravo cookbooks today are about half whale-based recipes. | |||

{{multiple image|perrow = 3|total_width=300 | |||

| align = left | |||

| image1 = Portrait Fortepan 18193.jpg | |||

| image2 = Major John Wesley Powell LCCN2004672794.jpg | |||

| image3 = Johannes Goetz by Wilhelm Fechner, c. 1900.png | |||

| image4 = Man, moustache, fashion, portrait Fortepan 4685.jpg | |||

| image5 = Edcope.jpg | |||

| footer = The Directory of 1893-1898: (clockwise from upper left) [[Lope de Juancho]], [[Rodolfo de Váez]], [[Gaspar Palacio]], [[Huw Weedy]], and [[Uriel Quizarro]] | |||

}} | |||

The 19th century was a peaceful period known as Pax Bravo. The islands were so remote, transport so slow, and the Bravo military so small that no wars reached Free Bravo, nor could Bravo forces extend elsewhere. Pax Bravo lasted 111 years from 1813 to 1924. Bravo soldiers were deployed only once in this time, to quell an 1848 whaler rebellion in Zeta Fe. | |||

The Directory governments of 1878-1883 (Alfaro-Brown-del Canto-Marzán-Quigley) and 1893-1898 (de Juancho-de Váez-Palacio-Quizarro-Weedy) oversaw widespread and rapid industrialization. Railways were built on islands large enough to require them. Domestic steamship passenger routes were established, vastly increasing the speed of inter-island transport. Industry was mechanized; a quarter of the workforce moved from agrarian to urban factory sectors. Free Bravo at the end of the century had the economic output of a marginal European state. An influx of foreign capital made it possible to modernize the military and expand urban centers. | |||

Free Bravo was a declared neutral during {{wp|World War I}}. British and {{wp|German Empire|German}} commercial fleets fought an antipodean trade war in Bravo ports—outbidding one another in purchases of fish and copper ore, ramming one another, and in three instances raiding Bravo warehouses and destroying stores to prevent the other nation from receiving them. In December 1916, the Directory (Bengoa-de Gordon-Madstone-Morón-Pinker) barred both nations from Bravo ports until the war's end. When Britain contrived for the {{wp|Entente Powers}} to cease grain trade with Free Bravo, the Directory relented and allowed British ships to return. German ships subsequently sank 7 Bravo fishing ships in the North Atlantic, killing 23 sailors. | |||

Tensions had long been simmering between {{wp|Argentina}} and Free Bravo over claims to Isla Roché y Las Últimas. When Argentina won independence from Spain in 1816, it declared as part of its territories the {{wp|Islas Malvinas}}, Isla Roché, and Las Últimas. The Argentine government claimed that the islands had never been ceded by Spain to Great Britain, and were Spanish territories at the time of Argentine independence. The {{wp|Peace of Utrecht|Peace and Friendship Treaty of Utrecht between Spain and Great Britain}} from 1713 says in Article XII: | |||

::''"Yet further the Catholic King doth in like manner for himself, his heirs and successors, yield to the crown of Great Britain the whole island of Costa Brava, and doth transfer thereunto for ever, all right, and the most absolute dominion over the said island, and in particular over the ports, places, and towns situated in the aforesaid island, and on all surrounding islands so belonging to the Captaincy General named Costa Brava."'' | |||

The Argentine position is that Isla Roché y Las Últimas are so distant from “the aforesaid island” that they cannot rightfully be considered one of “all surrounding islands”. As a result, it was never ceded by Spain to Great Britain. The {{wp|Nootka Conventions|Nootka Sound Conventions}} in 1790 further complicated matters, granting Spain and Great Britain equal rights to construct temporary settlements on the islands for fishery-related purposes (e.g. shelters and processing stations), provided that no non-Spanish or non-British party did otherwise. (Existing permanent settlements from either party were permitted.) The Argentines argued that post-independence Free Bravo settlements on Isla Roché y Las Últimas constituted a third-party trespass that invoked Argentina's right to settle the islands. Lastly, Argentina deemed porteño occupation in the years 1740-1743 a legitimate government which formed a continuum with modern Argentina. Most South American countries have historically recognized the Argentine claim. The Argentine claim was codified in the {{wp|Constitution of Argentina}} in {{wp|1994 amendment of the Constitution of Argentina|1994}}. Today, {{wp|China}} and all South American countries support Argentina except {{wp|Chile}} and {{wp|Venezuela}} ({{wp|Bolivia}} switched positions to support Argentina following the {{wp|2019 Bolivian political crisis|right-wing coup in 2019}}). Bravo jurists view the Argentine claim as "self-contradictory and misleading", in particular its basis in the muddled language of the Nootka Sound Conventions. | |||

Asserting Argentine sovereignty, President {{wp|Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear}} authorized a declaration of war on Free Bravo and the United Kingdom and invaded Islas Malvinas, Isla Roché, and Las Últimas on 10 October, 1924. This was the first action of the Air Wars. | |||

The {{wp|Atlantic Fleet (United Kingdom)|Atlantic Fleet}} of the United Kingdom immediately sailed for the South Atlantic with Admiral {{wp|Sir Henry Oliver}} on the flagship {{wp|HMS Revenge (06)|HMS ''Revenge''}}. A brief series of naval engagements crippled Argentina's navy—all but two Argentine ships had been constructed in the previous century. Argentina withdrew from Islas Malvinas and the United Kingdom left the war on 8 December, 1924. The Directory (Abasta-de Gordon-Madstone-Pousey-Venegas) unsuccessfully sued the {{wp|Second Baldwin ministry|government of the United Kingdom}} to remain in the war and assist the Free Bravo forces. | |||

[[File:HMS Argus (1917) cropped.jpg|thumb|right|The Free Bravo aircraft carrier ''El Restitucional'' in 1926]] | |||

[[File:Air Wars.jpg|thumb|right|Free Bravo forces mobilized, painting by [[Gutierre Waldo]], 1924]] | |||

Despite losing much of their naval capabilities, Argentina was able to retain control of Isla Roché y Las Últimas. A counterinvasion by the Free Bravo Navy on 14 December was repelled in a Pyrrhic victory for Argentina that rendered both navies basically inoperable for over a year. Successive naval battles resulted in similar stalemates: the [[Battle of Isla Errante]] on 12 January, 1926 and [[Battle of Hueco]] on 28 October, 1926 had no definite victors. | |||

[[File:Felixstowe F.2A - RNAS 1914-1918 Q27501.jpg|thumb|left|A seaplane of the Free Bravo Air Force ca. 1920]] | |||

[[File:Kamikawa Maru Aichi E13A seaplane.jpg|left|thumb|Air Corsairs under warlord Sami Akhtar]] | |||

The occupied islands were organized as the Autoridad Provisional de las Islas Argentinas, a transitional wartime province of Argentina. | |||

Guerrilla resistance on the islands was coordinated by telegraph from Nuevo Puerto Hercúles. Argentine anarchists were supported with paramilitary training by the Free Bravo military. {{wp|Severino Di Giovanni}}, one such anarchist, led a bombing campaign in Buenos Aires during the war. Free Bravo additionally drafted and commissioned all pilots within its borders as paramilitary pilots, enlisted international volunteer pilots, requisitioned mechanized factories such as automobile and shipbuilding factories to convert civilian aircraft into fighters and bomber planes, and converted whaling vessels into a flotilla of {{wp|seaplane tenders}}. This began the period of the Air Wars dominated by the so-called Air Corsairs. | |||

Originally conceived as a way to preserve the valuable personnel and materiel of the fledgling Free Bravo Air Force, the paramilitary Air Brigades took their Bravo funding and equipment and split into an array of rogue factions led by warlords. This included Rocheño and Ultimano guerrilla factions. A coalition of factions by air, land, and sea toppled the Autoridad Provisional in a campaign between February and June 1927. Rather than returning the islands to Free Bravo, they declared themselves a confederation of sovereign communes, the Territorios Libres. Fighting soon erupted between Argentine-aligned, Bravo-aligned, and non-aligned factions of the islands. The air forces of Free Bravo and Argentina entered the conflict directly in December 1927. A system of "alignment politics" prevented any one faction from gaining the upper hand: when one faction started to become too powerful, the rest would ally to stop them, then turn on each other. | |||

Bravo-aligned communist factions grew more ascendant towards the end of the Air Wars. [[Sol Fuerte]] and [[Ruy Octavio Picado]], two communist warlords, were vaunted as heroes throughout Free Bravo as they made sweeping territory gains and raided the Argentina mainland. | |||

This coincided with the {{wp|Great Depression}} which hit Free Bravo beginning in 1930. Slowdown of global trade and a precipitous fall in export prices caused total value of exports to decrease from ƒ700 million to ƒ330 million between 1930 and 1933. This was not to rise again to pre-1930 levels until 1938. Unemployment in 1932 was as high as 20%. This led to social unrest which coincided with agitation from {{wp|Universal suffrage|universal suffragists}} and advocates of political reform. The Directory (de Gordon-de Haro-Gil-Madstone-Singh) was extremely unpopular with approval at 13%, largely due to their inability to rectify economic conditions and resolve the Air Wars. There was a broader social disillusionment with the capitalist, oligarchic overclass which was over-represented in government. | |||

In early 1933, the Fuerte-Picado faction drove the Argentine remnants from Refugio, consolidating Bravo-aligned control over Isla Roché y Las Últimas. The Fuerte-Picadoes formed a Soviet-style directory government in Hueco. A peace accord between Argentina and the Fuerte-Picado government was signed on 30 March. Diplomatic overtures for reunification with Free Bravo were made, on the condition that the Hueco and Nuevo Puerto Hercúles directories were merged into a coalition national government. This happened on 9 September, 1933. The Directory (de Gordon-de Haro-Fuerte-Gil-Madstone-Picado-Singh) grew to 7 members. | |||

Concessions from the original Directory members towards the more radical Fuerte and Picado were slow to proceed. A snap election was contrived by Fuerte-Picado for 25 November, whose faction won an overwhelming victory, populating the new directory wholly with heroes of the Air Wars and other communists. The Directory (Akhtar-Badham-de la Torre-Fuerte-Picado-Sarkar-Xemen) immediately prorogued the government, abolished the constitution, and proclaimed the Armed Republic of Costa Bravo, a {{wp|socialist state}}. | |||

{{multiple image | |||

| total_width = 300 | |||

| image1 = Soledad Fuerte.png | |||

| image2 = Ruy Octavio Picado.png | |||

| footer = Soledad Fuerte and Ruy Octavio Picado, communist warlords and co-founders of the Armed Republic of Costa Bravo | |||

}} | |||

=== The Armed Republic of Costa Bravo (1933-1991) === | === The Armed Republic of Costa Bravo (1933-1991) === | ||

The [[Communist Revolutionary Party of Armed Struggle|Communist Revolutionary Party of Armed Struggle or Partido Comunista Revolucionario de la Lucha Armada]] (CPR or PCR) rapidly consolidated its power by liberating workers and tenants and allying Costa Bravo with the international socialist movement. Foreign and domestic trade became state-controlled, along with all commercial enterprise and industry. All private debt owed by the lowest-earning three quartiles of the population was cancelled. The country's 100 largest landowners had their lands expropriated, redistributed, and {{wp|Collective farming|collectivized}}. | |||

The directory remained the primary executive organ of government (absorbing judicial responsibility), while a subordinate [[Revolutionary Congress]] of lottery-selected representatives exercised limited legislative authority. Counter-revolutionaries such as former political leaders were exiled or imprisoned in labor camps, with an estimated 2500 people dying from state repression during the period 1933-1949. The new government resembled a Stalinist {{wp|Planned economy|centrally planned economy}} with significant divergence from the Soviet model in matters of culture and governance, in particular hewing more nationalist. Costa Bravo maintained an extremely close relationship with the {{wp|Soviet Union}} until after {{wp|World War II}}. | |||

Elections continued at regular five-year intervals, although candidates had to be selected by the Revolutionary Congress. While nominally a free process, this effectively resulted in a one-party state, as only members of CPR and CPR-satellite parties were ever selected. Fuerte and Picado (the ‘duumvirate’) dominated the politics of the Directory. | |||

In 1938, Fuerte and Picado began disagreeing on matters of isolationism, imperialism, and alignment with other socialist powers—Fuerte desired a more isolationist, nationalist character, while Picado was strongly Soviet-aligned. Divisions formed along these lines in the Directory and Revolutionary Congress. On 20 June, 1939, the Fuerte faction (which included Directory members ''Generalissimo of Air, Land, and Sea'' Sami Akhtar and ''Doctor-Director of Health and Social Services'' Eulália Bobo) launched a coup against Picado and his supporters. Street fighting erupted in Hueco and Nuevo Puerto Hércules. The coup forces were crushed within 3 days. Akhtar was killed in the fighting, Bobo was tried and exiled, and Fuerte was sentenced to death without trial, which was stayed at the last moment to life imprisonment. Fuerte lived in solitary confinement in [[Quefe Prison]] for 25 years. She escaped under mysterious circumstances in 1964 and disappeared. | |||

In late 1939, a flotilla of ocean liners carrying 3,000 Jewish refugees from {{wp|Nazi Germany}} arrived in Costa Bravo after being denied landing in Canada, the United States, and Argentina. The refugees were initially denied entry to Bravo ports as well, but when the captain of the lead ship MS ''Grobiana'' deliberately wrecked his vessel on the coast of Isla Roché, the Costa Bravo Navy was forced to rescue the passengers and accept the remainder of the flotilla who all threatened to do the same. Proportionally high European Jewish migration to Costa Bravo continued through {{wp|World War II}}. | |||

The Picado government was desirous of joining World War II from its outbreak in 1939. Fuerte faction remnants campaigned for Costa Bravo to remain a {{wp|neutral power}}. The Soviet Union also pressured Costa Bravo to stay out of the war in consideration of their {{wp|German-Soviet Pact|non-aggression pact}} with Germany. Tales of {{wp|The Holocaust|German atrocities}} related by Jewish refugees, plus a desire to assert a national military identity on the global stage, ultimately moved the Directory (Akbari-Badham-Barton-Hamad-Mamón-Picado-Velez) to declare war on the {{wp|Axis powers}} on 15 June, 1940. | |||

Costa Bravo was a major participant in the {{wp|East African campaign (World War II)|East African campaign}} (June 1940 to September 1941) and helped to suppress the {{wp|Italian guerrilla war in Ethiopia}} that followed (November 1941 to October 1943). Bravo paratroopers—which tactic had first been seen in Costa Bravo during the Air Wars—trained at the elite Air Raiders School in San Electrón were used widely in the Ethiopian theater. A fully modernized Costa Bravo Air Force dominated Italian veteran aces. | |||

From late 1941 to 1945, large portions of Costa Bravo forces assisted the Soviet Union in the {{wp|Eastern Front (World War II)|Eastern Front}}. The paracommando 1st Zouaves was highly decorated for its precise strike operations during the {{wp|Crimean offensive|Battle of the Crimea}}. | |||

The Costa Bravo Navy for the most part remained in home waters, with five {{wp|British H-class submarine|H-class submarines}} (including the ''Water Poppy'' and ''Loosestrife'') playing a key role in protecting Bravo shipping from the German and Japanese {{wp|Monsoon Group}} {{wp|U-boats}}. Four of the five Costa Bravo submarines were sunk in Operation Mother on 1 September, 1944—a successful raid which destroyed the submarine facilities of the {{wp|Port of Penang}} and ended the Axis threat in the Indian Ocean. | |||

An expansive seawall of some 10,000 {{wp|Naval mine#Contact mines|contact mines}} was deployed by Costa Bravo aerial minelayers in the Indian Ocean during the war to protect shipping lanes. About 5,000 additional mines were deployed in enemy coastal waters in Southeast Asia. Minesweeping the Indian Ocean seawall after the war proved too costly to be practicable. The dispersed mines are called wandering killers or muertes errantes and have proved dangerous on several occasions. A Japanese whaling vessel was severely damaged by a WW2-era Costa Bravo naval mine in 2002, while clusters of mines have intermittently washed ashore on Costa Bravo islands (notably in 1990 and 2014 on Isla Glande and Ye, respectively). | |||

* Pillar of the Third-World movement. Support for revolutionary movements throughout the world, from Black Panthers to Angola. | |||

* Acceptance of Jewish refugees in 1930s and 40s. Participation in World War II. | |||

* The Antarctic War, or the War at the Bottom of the World, fought 1960-1961 over land claims to Antarctica. Chile and Argentina backed by USA versus Costa Bravo backed by USSR. | |||

* Over the decades, the directory grew from 7 members, to 9, to 11, and finally to 13. | |||

* A depression in the 1970s set the stage for a workers' syndicalist revolution 1985-1991. | |||

=== The Free State of Costa Bravo (1991-present) === | === The Free State of Costa Bravo (1991-present) === | ||

| Line 201: | Line 288: | ||

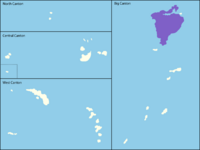

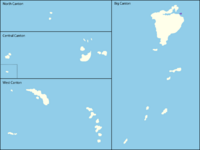

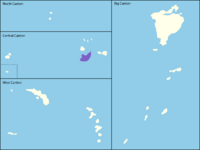

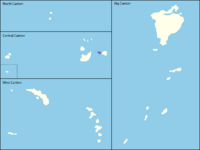

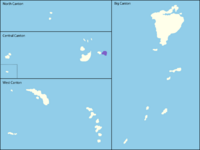

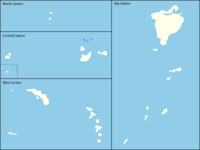

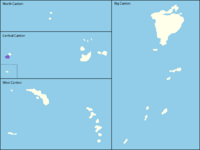

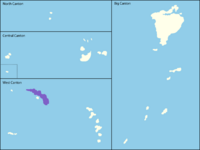

Costa Bravo is divided into 4 {{wp|Canton (country subdivision)|sea cantons}}: Big Canton, North Canton, Central Canton, and West Canton. | Costa Bravo is divided into 4 {{wp|Canton (country subdivision)|sea cantons}}: Big Canton, North Canton, Central Canton, and West Canton. | ||

{| class="wikitable mw-collapsible | {| class="wikitable sortable mw-collapsible" | ||

|+ class="nowrap" | <strong>Islands of Costa Bravo</strong> | |||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="col"| Location | |||

! scope="col"| Island | ! scope="col"| Island | ||

! scope="col"| Capital | ! scope="col"| Capital | ||

! scope="col"| | ! scope="col"| Sea canton | ||

! scope="col"| Postal code | ! scope="col"| Postal code | ||

! scope="col"| Total pop. | ! scope="col"| Total pop. | ||

! scope="col"| Notes | ! scope="col"| Notes | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Isla Grande | ! scope="row"| [[File:IslaGrandeloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Nuevo Puerto Hércules | | '''[[Isla Grande]]''' | ||

| [[Nuevo Puerto Hércules]] | |||

| Big | | Big | ||

| GRA | | GRA | ||

| | | 1,201,589 | ||

| Simply referred to as the main island. Other cities include San Electrón. | | Simply referred to as the main island. Other cities include [[San Electrón]]. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Isla Glande | ! scope="row"| [[File:IslaGlandeloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Atroz Aires | | '''[[Isla Glande]]''' | ||

| [[Atroz Aires]] | |||

| Big | | Big | ||

| GLA | | GLA | ||

| | | 205,457 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| El Haz de Luz | ! scope="row"| [[File:ElHazloc.png|200px]] | ||

| El Haz de Luz | | '''[[El Haz de Luz]]''' | ||

| [[El Haz de Luz]] | |||

| Big | | Big | ||

| HAZ | | HAZ | ||

| | | 30,201 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Miranda | ! scope="row"| [[File:Mirandaloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Zeta Fe | | '''[[Miranda]]''' | ||

| [[Zeta Fe]] | |||

| Big | | Big | ||

| MIR | | MIR | ||

| | | 1,550,630 | ||

| Other settlements include [[Turdueles]]. | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row"| [[File:Antiguoloc.png|200px]] | |||

| '''[[Antiguo]]''' | |||

| [[Espartaco]] | |||

| Big | |||

| ANT | |||

| 110,457 | |||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Ramita del Mar | ! scope="row"| [[File:Ramitaloc.png|200px]] | ||

| La Salinidad | | '''[[Ramita del Mar]]''' | ||

| [[La Salinidad]] | |||

| Big | | Big | ||

| RAM | | RAM | ||

| | | 7,996 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Perdido | ! scope="row"| [[File:Perdidoloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Santa Bondad | | '''[[Perdido]]''' | ||

| [[Santa Bondad]] | |||

| Big | | Big | ||

| PER | | PER | ||

| | | 12,223 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Heladino | ! scope="row"| [[File:Heladinoloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Paragüero | | '''[[Heladino]]''' | ||

| [[Paragüero]] | |||

| Big | | Big | ||

| HEL | | HEL | ||

| | | 9,507 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Nueva Ymana del Sur | ! scope="row"| [[File:Ymanaloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Contranorte | | '''[[Nueva Ymana del Sur]]''' | ||

| [[Contranorte]] | |||

| Big | | Big | ||

| YMA | | YMA | ||

| | | 25,855 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Puerco Roco | ! scope="row"| [[File:Puercoloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Bombavista | | '''[[Puerco Roco]]''' | ||

| [[Bombavista]] | |||

| Central | | Central | ||

| PUE | | PUE | ||

| | | 4,250 | ||

| One of the Islas de la Cruz. | | One of the [[Islas de la Cruz]]. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Tierra del Huevo | ! scope="row"| [[File:Huevoloc.png|200px]] | ||

| San Barto | | '''[[Tierra del Huevo]]''' | ||

| [[San Barto]] | |||

| Central | | Central | ||

| HUE | | HUE | ||

| | | 701,540 | ||

| One of the Islas de la Cruz. | | One of the Islas de la Cruz. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Posesión | ! scope="row"| [[File:Posesionloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Buenas Nuevas | | '''[[Posesión]]''' | ||

| [[Buenas Nuevas]] | |||

| Central | | Central | ||

| POS | | POS | ||

| | | 3,231 | ||

| One of the Islas de la Cruz. | | One of the Islas de la Cruz. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Donación | ! scope="row"| [[File:Donacionloc.png|200px]] | ||

| El Morado | | '''[[Donación]]''' | ||

| [[El Morado]] | |||

| Central | | Central | ||

| DON | | DON | ||

| | | 20,641 | ||

| One of the Islas de la Cruz. | | One of the Islas de la Cruz. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Islotes de Satanazes | ! scope="row"| [[File:Satanazesloc.png|200px]] | ||

| '''[[Islotes de Satanazes]]''' | |||

| None | | None | ||

| Central | | Central | ||

| None | | None | ||

| | | 1 | ||

| A group of small rocky islands near the Islas de la Cruz. | | A group of small rocky islands near the Islas de la Cruz. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Costaguana | ! scope="row"| [[File:Costaguanaloc.png|200px]] | ||

| | | '''[[Costaguana]]''' | ||

| [[Cargoburgo]] | |||

| Central | | Central | ||

| COS | | COS | ||

| | | 308,476 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Ronagua | ! scope="row"| [[File:Ronagualoc.png|200px]] | ||

| Ultra Marino | | '''[[Ronagua]]''' | ||

| [[Ultra Marino]] | |||

| Central | | Central | ||

| RON | | RON | ||

| | | 9,552 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Isla Errante | ! scope="row"| [[File:IslaErranteloc.png|200px]] | ||

| '''[[Isla Errante]]''' | |||

| None | | None | ||

| Central | | Central | ||

| ERR | | ERR | ||

| | | 0 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Isla Roché | ! scope="row"| [[File:IslaRocheloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Hueco | | '''[[Isla Roché]]''' | ||

| [[Hueco]] | |||

| West | | West | ||

| ROC | | ROC | ||

| | | 1,102,262 | ||

| The second largest island. Other settlements include Baja Haya and Plebezuela. | | The second largest island. Other settlements include [[Baja Haya]] and [[Plebezuela]]. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Poco Rojo | ! scope="row"| [[File:Pocoloc.png|200px]] | ||

| '''[[Poco Rojo]]''' | |||

| None | | None | ||

| West | | West | ||

| POC | | POC | ||

| 0 | |||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Última | ! scope="row"| [[File:UltColloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Las | | '''[[Última Colonia]]''' | ||

| [[Colonia]] | |||

| West | |||

| COL | |||

| 99,356 | |||

| One of Las Últimas. | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row"| [[File:UltPoploc.png|200px]] | |||

| '''[[Última Populania]]''' | |||

| [[Gran Gracos]] | |||

| West | | West | ||

| | | POP | ||

| | | 208,494 | ||

| One of Las Últimas. | | One of Las Últimas. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Última Medio | ! scope="row"| [[File:UltMedioloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Cobreville | | '''[[Última Medio]]''' | ||

| [[Cobreville]] | |||

| West | | West | ||

| MED | | MED | ||

| | | 95,416 | ||

| One of Las Últimas. | | One of Las Últimas. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| | ! scope="row"| [[File:UltFloloc.png|200px]] | ||

| '''[[Última Florea]]''' | |||

| [[Florinata]] | |||

| | |||

| Florinata | |||

| West | | West | ||

| FLO | | FLO | ||

| | | 65,551 | ||

| One of Las Últimas. | | One of Las Últimas. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Última Gota | ! scope="row"| [[File:UltGotloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Yerba Buena | | '''[[Última Gota]]''' | ||

| [[Yerba Buena]] | |||

| West | | West | ||

| GOT | | GOT | ||

| | | 20,506 | ||

| One of Las Últimas. | | One of Las Últimas. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Última | ! scope="row"| [[File:UltTulloc.png|200px]] | ||

| | | '''[[Última Tule]]''' | ||

| [[Las Adelfas]] | |||

| West | | West | ||

| | | TUL | ||

| | | 105,877 | ||

| One of Las Últimas. | | One of [[Las Últimas]]. | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Refugio | ! scope="row"| [[File:Refugioloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Nuevo Viejo | | '''[[Refugio]]''' | ||

| [[Nuevo Viejo]] | |||

| West | | West | ||

| REF | | REF | ||

| | | 2,502 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Isla Sano | ! scope="row"| [[File:IslaSanoloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Villa Libre | | '''[[Isla Sano]]''' | ||

| [[Villa Libre]] | |||

| West | | West | ||

| SAN | | SAN | ||

| | | 2,962 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Isla de la Plaga | ! scope="row"| [[File:IslaPlagaloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Lazaretta | | '''[[Isla de la Plaga]]''' | ||

| [[Lazaretta]] | |||

| West | | West | ||

| PLA | | PLA | ||

| | | 1,256 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Ye | ! scope="row"| [[File:Yeloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Dar es Coba | | '''[[Ye]]''' | ||

| [[Dar es Coba]] | |||

| North | | North | ||

| YED | | YED | ||

| | | 11,825 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Zeda | ! scope="row"| [[File:Zedaloc.png|200px]] | ||

| Jauja | | '''[[Zeda]]''' | ||

| [[Jauja]] | |||

| North | | North | ||

| ZED | | ZED | ||

| | | 34,364 | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 433: | Line 552: | ||

== Environment == | == Environment == | ||

{{climate chart | |||

| Costa Bravo mean temperature and precipitation | |||

| 11.7 | 19.6 | 53.8 | |||

| 8.8 | 16.7 | 65.0 | |||

| 5.6 | 13.2 | 100.1 | |||

| 3.4 | 10.3 | 113.0 | |||

| 1.6 | 8.2 | 113.4 | |||

| 1.4 | 6.9 | 168.4 | |||

| 0.8 | 6.3 | 169.4 | |||

| 3.5 | 9.2 | 188.9 | |||

| 7.0 | 13.5 | 120.8 | |||

| 10.8 | 18.9 | 91.1 | |||

| 13.8 | 22.2 | 72.6 | |||

| 13.7 | 22.2 | 50.1 | |||

|float=right | |||

|date=2017 }} | |||

Costa Bravo is located in and around the {{wp|Subantarctic|subantarctic zone}}. Warm winds delivered by the {{wp|Indian Ocean gyre}} and the {{wp|South Atlantic gyre}} create a {{wp|Oceanic climate|temperate oceanic}} climate on many islands. Smaller outlying islands are {{wp|subarctic}}. All parts of the nation experience mild to cool summers, with windy and wet winters. Precipitation is constant throughout the year. There is a Bravo joke—Question: "¿Estamos en primavera/verano/otoño/invierno?" Answer: "It is drizzling." | Costa Bravo is located in and around the {{wp|Subantarctic|subantarctic zone}}. Warm winds delivered by the {{wp|Indian Ocean gyre}} and the {{wp|South Atlantic gyre}} create a {{wp|Oceanic climate|temperate oceanic}} climate on many islands. Smaller outlying islands are {{wp|subarctic}}. All parts of the nation experience mild to cool summers, with windy and wet winters. Precipitation is constant throughout the year. There is a Bravo joke—Question: "¿Estamos en primavera/verano/otoño/invierno?" Answer: "It is drizzling." | ||

The biome on larger islands is {{wp| | The biome on larger islands is {{wp|laurel forest}}, with mild temperatures, high humidity, and broadleaved forest cover. Subarctic and outlying islands are windswept, scrubby, {{wp|Boreal Kingdom|boreal}} or {{wp|Antarctic Floristic Kingdom|holantarctic}} biomes, with dense low-lying tree cover such as {{wp|Phylica arborea|Island Cape myrtle}} on Zeda. The majority of islands are potentially active volcanoes. Costa Bravo has not experienced a sizable eruption anywhere since 1974 when [[El Revolucionario Ardiente]] erupted on Tierra del Huevo, severely damaging the city of San Barto. | ||

=== Flora & fauna === | === Flora & fauna === | ||

Wildflower species predominate the boreal grasslands. In spring and fall, the islands are awash with color. Wildflower species include | |||

There are several endemic animal species in Costa Bravo. The dagger-toothed or dagadiente cat (''Felis bravis'') is a national symbol. It was introduced by Austronesian settlers in the first millennium or early second millennium CE. It has the longest canine teeth of any living feline (hence its name) and a puffy banded tail. The giant stilt-owl (''Grallistrix vomitus''), a 1 meter tall flightless terrestrial owl, is the only extant species of its kind. The giant stilt-owl is a nocturnal predator, feeding on small birds and mammals on the forest floor. It is preyed upon in turn by the dagger-toothed cat. Its primary defense mechanism is vomiting up a foul mixture of stomach contents and blood before running away at high speeds. The endangered pink ibis (''Threskiornis rosaceae'') is a solitary bird with small populations on Isla Grande and the Islas de la Cruz. It is an awkward flier loathe to travel long distances. The blue-headed wigeon (''Mareca mirabila'') is a small flightless duck related to the extinct {{wp|Amsterdam wigeon|Zeda wigeon}}. The Bravo shag (''Leucocarbo verrucosus'') is a cormorant with protected colony nests on islands in Big Canton. The giant crab-eating rat (''Rattus carceris'') is descended from rat populations from shipwrecks of the 16th and 17th centuries. It lives on scrubby beaches and eats crabs, molluscs, and fish, being able to swim some distances in open ocean. Its water-repelling shaggy fur keeps it warm and dry. The Bravissimo pipit (''Anthus antarcticus'') is a sparrow-sized songbird. | |||

Costa Bravo is an important mating site for several dozen species, including albatrosses, terns, penguins, and seals. The surrounding waters are home to numerous fish and cetaceans, such as the {{wp|Antarctic toothfish}}, {{wp|skunk dolphin}}, and {{wp|southern minke whale}}. | |||

<div style="text-align: center;">'''Endemic species'''</div> | |||

<gallery mode="packed-hover"> | |||

Image:Dagadiente.png|Dagger-toothed or dagadiente cat | |||

Image:Stilt-owl.png|Giant stilt-owl | |||

Image:Pink ibis.jpg|Pink ibis | |||

Image:Blueheaded wigeon.png|Blue-headed wigeon | |||

Image:TAAF - Archipel de Kerguelen - cormoran des Kerguelen en face de la base de Port Aux Français.jpg|Bravo shag | |||

Image:Giant crab-eating rat.jpg|Giant crab-eating rat | |||

</gallery> | |||

<div style="text-align: center;">'''Seabirds'''</div> | |||

<gallery mode="packed-hover"> | |||

Image:Giant petrel.jpg|Petrels | |||

Image:Stercorarius parasiticus1.jpg|Skuas | |||

Image:Gentoo Penguins (24940363035).jpg|Penguins | |||

Image:Chionis_-_panoramio.jpg|Sheathbills | |||

Image:Great Shearwater RWD9r.jpg|Shearwaters | |||

Image:Slender-billed_Prion_Close.jpg|Prions | |||

Image:Short-tailed Albatross Chick 2012 (6721781737).jpg|Albatrosses | |||

Image:Seagull eating starfish.jpg|Gulls | |||

Image:Sterne de Kerguelen.jpg|Terns | |||

</gallery> | |||

<div style="text-align: center;">'''Marine species'''</div> | |||

<gallery mode="packed-hover"> | |||

Image:Uma Baleia Anã nos Açores, version 2.jpg|Southern minke whale | |||

Image:Arnoux's beaked whale.jpg|Giant beaked whale | |||

Image:Sei whale mother and calf Christin Khan NOAA(1).jpg|Sei rorqual | |||

Image:Type C OrcasEdit1.jpg|Orca | |||

Image:CommersondolphinArgentina.jpg|Skunk dolphin | |||

Image:Hourglas dolphin crop.jpg|Cruzado dolphin | |||

Image:Porpoise.org-adopt-a-spectacled-porpoise-spectacled-porpoise-promo.jpg|Spectacled porpoise | |||

Image:Leucistic Antarctic Fur Seal (5810279673).jpg|Antarctic fur seal | |||

Image:2498-sea-lion-elephant-seals RJ.jpg|Southern elephant seal | |||

Image:Dmawsoni Head shot.jpg|Toothfish | |||

Image:Krillmeatkils.jpg|Krill | |||

Image:CSIRO ScienceImage 2839 Spiny Stone King Crab.jpg|Spiny king crab | |||

Image:Blue crab.jpeg|Blue crab | |||

</gallery> | |||

== Economy == | == Economy == | ||

| Line 445: | Line 625: | ||

[[File:Economic treemap of Costa Bravo.png|right|thumb|Goods exported by Costa Bravo.]] | [[File:Economic treemap of Costa Bravo.png|right|thumb|Goods exported by Costa Bravo.]] | ||

Production in all industries is controlled by cooperatives. These cooperatives may range from just a few people to a nationwide organization of tens of thousands of workers. Cooperatives are managed collectively with one vote per member. The profit of a cooperative is split three ways: the first part is spent on planned production and future projects (usually 30%), the second part is divided between the workers according to their needs and expended efforts (usually 50%), and the third part is spent on the immediate needs of the members: healthcare, education, electricity, water, infrastructure, etc. (usually 20%). The exact proportions vary by cooperative. This collective economy is in contrast with a {{wp|Capitalism|capitalist}} system, in which a worker's profits are taken by an individual or a few individuals and then returned in a small portion back to the worker as wages. There is no stock market in Costa Bravo. | Production in all industries is controlled by cooperatives. These cooperatives may range from just a few people to a nationwide organization of tens of thousands of workers. Cooperatives are managed collectively with one vote per member. The profit of a cooperative is split three ways: the first part is spent on planned production and future projects (usually 30%), the second part is divided between the workers according to their needs and expended efforts (usually 50%), and the third part is spent on the immediate needs of the members: healthcare, education, electricity, water, infrastructure, etc. (usually 20%). The exact proportions vary by cooperative. This collective economy is in contrast with a {{wp|Capitalism|capitalist}} system, in which a worker's profits are taken by an individual or a few individuals and then returned in a small portion back to the worker as wages. There is no stock market in Costa Bravo. | ||

[[File:Samsung digital camera (7017545581).jpg|thumb|left|A cut flower distribution center in Cargoburg]] | |||

As of 2017, the nation is ranked 7th in the world on the {{wp|Human Development Index}} and is ranked 1st in the world for {{wp|Gini coefficient|income equality}}. | |||

Uranium and thorium mining is the largest single sector of the economy, with Costa Bravo possessing the second-largest world thorium reserves behind {{wp|India}}. Thorium-powered {{wp|nuclear power plants}} provide almost two-thirds of the energy needs of the nation. Agricultural exports in the form of flowers and flower-based products make up the other primary sector of the economy. Flower products including perfumes comprise 46% of all exports. Costa Bravo provides one-third of the world's total flower products, an amount equal to the {{wp|Netherlands}}. Food-based agriculture is generally oriented towards self-sufficiency rather than surplus for export, with the notable exception of tea production. | |||

Uranium and thorium mining is the single | |||

Historically, whaling has been the largest sector of the economy. However, following the {{wp|International Whaling Commission}}'s ban on the international trade of whale products in 1982, the whaling industry in Costa Bravo has shrunk considerably. The creation of the {{wp|Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary}} in 1994 led to diplomatic and trade sanctions, as Bravo whalers continued harvesting from those waters. Two nationwide referendums in 1999 and 2006 proposing a domestic ban on whaling were defeated by slim majorities. The IWC has accused Costa Bravo of participating in illegal international trade of whale parts with {{wp|Iceland}} and {{wp|Japan}}. | Historically, whaling has been the largest sector of the economy. However, following the {{wp|International Whaling Commission}}'s ban on the international trade of whale products in 1982, the whaling industry in Costa Bravo has shrunk considerably. The creation of the {{wp|Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary}} in 1994 led to diplomatic and trade sanctions, as Bravo whalers continued harvesting from those waters. Two nationwide referendums in 1999 and 2006 proposing a domestic ban on whaling were defeated by slim majorities. The IWC has accused Costa Bravo of participating in illegal international trade of whale parts with {{wp|Iceland}} and {{wp|Japan}}. | ||

| Line 454: | Line 634: | ||

=== Transport === | === Transport === | ||

The | Costa Bravo possesses the most extensive undersea transport network in the world. Isla Grande is connected by undersea railway tunnels to [[Isla Glande]], [[El Haz de Luz]], [[Miranda]], and [[Antiguo]]. The island chains of [[Islas de la Cruz]] and [[Las Últimas]] are connected by undersea railway tunnels as well. {{wp|High-speed craft|High-speed ferries}} have routes between all islands, with most craft in the ferry fleet boasting speeds between 60-80 knots, the fastest HSC ferries in the world. {{wp|Flying boat|Passenger seajets}} (also known as flying boats or hidrocanoas) fly domestically on 15 different routes. All public transport is free for residents of Costa Bravo, including domestic seajet flights. | ||

Personal automobiles have been banned in Costa Bravo since 1991. Community motor pools provide publicly-owned cars, trucks, motorized scooters, and motorcycles, with a limit on the number allowed per municipality. Organizations such as cooperatives may own their own automobiles for work purposes. Buses and emergency service vehicles are also fully utilized. Cycling has a {{wp|modal share}} of 52% of all trips nationwide, followed by public transit at 45%. Cycling infrastructure based on the {{wp|Cycling in the Netherlands|Dutch model}} is highly funded and state-of-the-art on all islands—for each kilometer of roadway, there exists three times as much of protected {{wp|cycleways}}. | |||

=== Labor rights === | |||

=== Currency === | |||

The nationally minted currency is the Costa Bravo Florín (FLO) ({{wp|USD}} $.10). Floríns are vertically oriented polymer banknotes, having been made plastic starting in 1991. Prior to the polymerization of paper currency, Floríns were printed on hemp paper. All denominations are the same size and format, as per the US dollar, but are easily distinguishable by color. Paper denominations are 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100. Decimal coins are 5, 10, 25, and 100. Coins carry the likeness of animals, and banknotes plants. | |||

== Culture == | == Culture == | ||

| Line 460: | Line 648: | ||

=== Demographics === | === Demographics === | ||

Costa Bravo is entirely a visa-free zone with open borders. A visa or residence permit are not required to live or work in Costa Bravo. All people including citizens, visitors, and resident aliens have equal legal rights, including {{wp|right of abode}}. International points of entry do have a customs system that prohibits entry of hazardous materials, illegal items, and agricultural pests, but no person may be denied entry except in the most exigent circumstances. | |||

=== Media === | === Media === | ||

| Line 466: | Line 654: | ||

In the early history of Costa Bravo, {{wp|pamphleteering}} by underground printing presses was epidemic. Today, there are hundreds of newspapers and magazines across Costa Bravo of varying circulation sizes and professionalism. Some wide-circulation publications focus on global issues while others relate only the current events of a single city neighborhood. Many political organizations publish their own newspaper. As is the case with all media in Costa Bravo, news publications switch freely between English and Spanish on the same page. | In the early history of Costa Bravo, {{wp|pamphleteering}} by underground printing presses was epidemic. Today, there are hundreds of newspapers and magazines across Costa Bravo of varying circulation sizes and professionalism. Some wide-circulation publications focus on global issues while others relate only the current events of a single city neighborhood. Many political organizations publish their own newspaper. As is the case with all media in Costa Bravo, news publications switch freely between English and Spanish on the same page. | ||

''The Signal'' is the most circulated newspaper, focusing on all issues national, subnational, and international. ''The All-Bravo'' focuses on Bravo affairs. Other newspapers include ''The Common Voice'', ''The People's Tribune'', and ''The Screamin' Plebeian''. | ''The Signal'' is the most circulated newspaper, focusing on all issues national, subnational, and international. ''The All-Bravo'' focuses on Bravo affairs. Other newspapers include ''The Common Voice'', ''The People's Tribune'', and ''Las Plebedades'' or ''The Screamin' Plebeian''. | ||

Sea People's Pirate Radio (SPPR) is the most popular news radio station. It was established in the 1970s as a {{wp|pirate radio}} music station. During the Civil War, it broadcast updates from the revolutionary struggle. Its news journalism | Sea People's Pirate Radio (SPPR) is the most popular news radio station. It was established in the 1970s as a {{wp|pirate radio}} music station. During the Civil War, it broadcast updates from the revolutionary struggle when news was suppressed by the government. Its news journalism became its primary focus after the war. SPPR programs are still transmitted from an offshore platform in international waters. | ||

Television stations are public access and do not require a license. As with publications, there is a proliferation of televised networks from the local to the national level. The nationwide Bravo People’s Network (BPN) is the most-watched station. The longest-running Bravo television show is | Television stations are public access and do not require a license. As with publications, there is a proliferation of televised networks from the local to the national level. The nationwide Bravo People’s Network (BPN) is the most-watched station. The longest-running Bravo television show is ''Secrets of the Stone'', a half-hour Saturday morning documentary program about the [[Satan Stone]] in which experts and amateurs present their theories concerning its purpose, the meaning of its glyphs, and so forth. ''Secrets of the Stone'' has aired about 3500 episodes on BPN since 1957. | ||

=== Sports === | === Sports === | ||

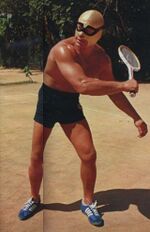

[[File:El Gran Rudo.jpg|thumb|150px|El Gran Rudo, tenis libre champ and sex symbol]] | |||

The three most popular sports are {{wp|rugby 7s}}, {{wp|hurling}}, and a theatrical form of populist ‘street tennis’ called tenis libre or freestyle tennis in which the tenista (tennis player) resembles a luchador. Baseball and soccer are widely enjoyed at a nonprofessional level. All sports are mixed-sex. | |||

The top-level Rugby 7s competition is [[Ultra League]] (first season 1933); the equivalent for hurling is [[Super League]] (first season 1930). The rugby season generally takes place from February to June. The hurling season takes place from August to December. Tenis libre is played throughout the year. | |||

Costa Bravo has no {{wp|National Olympic Committee}}, although it has produced a number of Olympic and Paralympic champions. All Bravo athletes compete as {{wp|Independent Olympians at the Olympic Games|Independent Olympians}} under the Olympic Flag. | |||

{| class="wikitable sortable" style="width: 85%" style="text-align:center" style="display: inline-table;" | |||

|- | |||

|+Rugby 7s Ultra League | |||

|- | |||

! width:18%" | Team | |||

! width:8%" | Established | |||

! width:23%" | City | |||

! width:12%" | Titles (Last) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Alley Cats]] | |||

|1910 | |||

|[[Nuevo Puerto Hércules]] | |||

|13 (2009) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Boom]] | |||

|1981 | |||

|[[El Haz de Luz]] | |||

|2 (1984) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Enzymes]] | |||

|1949 | |||

|[[Las Adelfas]] | |||

|7 (2017) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Fighting Fossils]] | |||

|1919 | |||

|[[Gran Gracos]] | |||

|9 (2018) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Foxbats]] | |||

|1910 | |||

|[[Hueco]] | |||

|16 (2019) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Free Radicals]] | |||

|1924 | |||

|[[Cobreville]] | |||

|9 (2009) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Haze]] | |||

|1920 | |||

|[[Atroz Aires]] | |||

|4 (2004) | |||

|- | |||

|[[River Rats]] | |||

|1910 | |||

|[[San Barto]] | |||

|12 (2013) | |||

|- | |||

|[[X-rays]] | |||

|1925 | |||

|[[Zeta Fe]] | |||

|6 (1989) | |||

|} | |||

{| class="wikitable sortable" style="width: 85%" style="text-align:center" style="display: inline-table;" | |||

|- | |||

|+Hurling Super League | |||

|- | |||

! width:18%" | Team | |||

! width:8%" | Established | |||

! width:23%" | City | |||

! width:12%" | Titles (Last) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Artistas]] | |||

|1930 | |||

|[[Colonia]] | |||

|5 (1999) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Contrabandistas]] | |||

|1934 | |||

|[[Hueco]] | |||

|0 (N/A) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Cuáqueros]] | |||

|1929 | |||

|[[Cargoburgo]] | |||

|3 (1977) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Floreros]] | |||

|1929 | |||

|[[Florinata]] | |||

|9 (2019) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Gaélicos]] | |||

|1929 | |||

|[[San Electrón]] | |||

|15 (2018) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Jefes]] | |||

|1930 | |||

|[[Jauja]] | |||

|12 (2013) | |||

|- | |||

|[[Partisanos]] | |||

|1930 | |||

|[[Espartaco]] | |||

|15 (2009) | |||

|} | |||

=== Education === | === Education === | ||

Education is compulsory for all minors in Costa Bravo and completely free. There is no extended vacation period in the summer months, but rather 12 weeks of holiday periods interspersed throughout the year. Curriculum is | Education is compulsory for all minors in Costa Bravo and completely free. There is no extended vacation period in the summer months, but rather 12 weeks of holiday periods interspersed throughout the year. Curriculum is standardized across all regions, with particular emphasis on ideological training, labor history, work training, religious education, and the arts. In upper secondary school, students may optionally enroll in off-campus militia training for school credit. | ||

Universities, trade schools, and technical institutes are also tuition-free. About 60% of Bravoes attend an institution of higher learning. Universidad Hercúlea and Libre Politécnico de Costa Bravo are two of the most prestigious universities. | |||

Homeschooling is prohibited. | |||

=== Holidays === | |||

There are nine primary national holidays, during which many industries are closed. Different municipalities may commemorate additional days, for example the [[Twelve Days of Hercules]] (20 July-31 July) in Nuevo Puerto Hércules. Workers receive full paid time off for national holidays and religious observances. | |||

* 1 January: {{wp|New Year's Day}} | |||

* 1 April: [[Day of Triumph]] | |||

* 15 April: {{wp|Arbor Day}} | |||

* 22 April: {{wp|Earth Day}} | |||

* 28 April: {{wp|Workers’ Memorial Day}} | |||

* 1 May: {{wp|May Day}} | |||

* 21 September: [[Students' Day]] | |||

* 1-2 November: [[Festival of Souls]] | |||

* 1 December: [[Field Day]] | |||

With four designated national holidays, April is known as Month of the Bravoes. Other holidays routinely celebrated include {{wp|Halloween|Halloween or Noche de los Difuntos}} on 31 October, {{wp|Valentine’s Day|Day of Love and Friendship}} on 14 February, {{wp|Women’s Day}} on 8 March, and {{wp|Men’s Day}} on 19 November, the latter two serving a similar role as Mother’s Day and Father’s Day in other countries. A {{wp|List of LGBT awareness periods|Non-Binary People’s Day}} on 14 July (directly between Women’s Day and Men’s Day) has grown in practice since 2017, mostly among students. | |||

== Symbols of Costa Bravo == | == Symbols of Costa Bravo == | ||

Latest revision as of 17:29, 5 February 2020

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Free State of Costa Bravo Estado Libre de Costa Bravo | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| Motto: "Trabajadores, unite!" | |

| Anthem: The Internationale/La Internacional | |

Location of Costa Bravo (purple) | |

| Capital | Nuevo Puerto Hércules |

| Official languages | None |

Local languages | a la brava |

| Ethnic groups (2019) | 29.0% European 18.6% South Asian 16.0% African 10.9% Asian 9.6% Polynesian 8.9% West Asian 7.0% other |

| Religion (2019) | 33.1% Liberational Catholicism 20.8% Buddhism 13.0% Hinduism 10.4% Islam 9.9% Quakerism 7.6% Judaism 5.3% other |

| Demonym(s) | Bravo |

| Government | Democratic confederalism (Devolved council democracy government on a confederated model with syndicalist traditions) |

| Stages of sovereignty | |

• Discovery by Europeans | 1522 |

• Colonization by Spain | 1580 |

• Ceded to Great Britain | 1714 |

• Independence | 1812 |

• Abolition of the directory system | 1991 |

| Area | |

• Total | 199,052 km2 (76,854 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 6.9 |

| Population | |

• 2019 census | 5,051,977 (+900,000 resident aliens) |

• Density | 25/km2 (64.7/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | estimate |

• Total | ƒ80 trillion |

• Per capita | ƒ548,210 |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Total | ƒ70 trillion |

• Per capita | ƒ359,340 |

| Gini | low |

| HDI | very high |

| Currency | Costa Bravo Florín (ƒ) (FLO) |

| Time zone | UTC+3:00 (UTC) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +666 |

| Internet TLD | .cb |