Manjugurun: Difference between revisions

| Line 932: | Line 932: | ||

| list1 = | | list1 = | ||

* {{AUS}} | * {{AUS}} | ||

* {{ | * {{flagicon|Austria}} {{wpl|Austria}} | ||

* {{BEL}} | * {{BEL}} | ||

* {{CAN}} | * {{CAN}} | ||

* {{ | * {{flagicon|China}} {{wpl|China}} | ||

* {{CZE}} | * {{CZE}} | ||

* {{DEN}} | * {{DEN}} | ||

Revision as of 19:09, 30 March 2020

State of Manchuria Манҗу Гурун ᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡬᡠᡵᡠᠨ 满洲国 Государство Маньчжурия 만주국 マンシュウコク манж улс ᠠᠨᠵ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ | |

|---|---|

Anthem:

| |

location of Manchuria in green | |

| Capital | Cangcon[a] |

| Largest city | Mukden |

| Official languages | Manchu (official and national), Mandarin, Russian, Korean, Japanese, Mongolian |

| Official scripts | Manchu Cyrillic Manchu script |

| Ethnic groups (2010) | |

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary state |

| Bai Chunli | |

• Founder | Aisin Gioro Yujang |

| Citela Sucun | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Formation | |

| formed 1115 | |

| formed 1636 | |

| 1932 | |

• Manchurian People's Republic was established | February 1, 1946 |

• Sorghum Revolution | October 3, 1990 |

| February 1, 1991 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,260,000 km2 (490,000 sq mi) (18th) |

• Water (%) | 5.4 |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 121,163,770 (134th) |

• Density | 96.1/km2 (248.9/sq mi) (67th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $4.50 trillion |

• Per capita | $37,084 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $4.06 trillion |

• Per capita | $33,493 |

| Gini (2013) | 36.5 medium |

| HDI (2015) | medium |

| Currency | Jiha (MNJ) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 |

| Date format | yyyy.mm.dd (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +976 |

| ISO 3166 code | MN |

| Internet TLD | .mj, .ман |

| |

Manchuria /mæŋˈtʃuːriə/ (listen) (Manju Gurun in Manchu; Манҗу Гурун in Manchu Cyrillic) is a sovereign state in East Asia. It borders Russia to the north, Mongolia to the west, China to the southwest, and Korea in the southeast. Its capital is Changchun, and its former capital Mukden is the largest city. Its population of 121,204,300 is one of the largest on earth.Template:UN Population

While Manchuria was dominated by Korean and Chinese dynasties, they were mostly dominated by Tungusic peoples such as the Jurchens. The region was the center of the Jin Dynasty from 1125 to 1234, when it was conquered by the Mongol Empire and its Yuan Dynasty. Southern Manchuria fell under Ming rule, but the northern parts remained outside Chinese control. The Jianzhou Jurchen chieftain Nurhaci later took over the Jurchen tribes in the 1600s, culminating in the Qing Dynasty founded by Hong Taiji in 1636, and later conquering China by 1644. Intrigues by Russia led to the loss of Outer Manchuria by 1860, with Manchuria coming under Russian influence by the late 19th century. The southern part was also later influenced by Japan by the early 1900s. By 1911, the Qing Dynasty fell and Manchuria went to a sway of Chinese warlords such as Zhang Xueliang.[1] and is considered the homeland of several groups besides the Manchus, including the Koreans and Chinese. [2][3][4]Japan's influence increased by 1932, later establishing Manchukuo as a satellite state, with the last emperor of Qing and China, Pu Yi being installed as a puppet leader. Popular resistance against Japanese rule intensified, and by the end of World War II, a pro-Communist parallel government took over most parts of Manchuria, co-operating with coup-plotters in Xinjing and the Soviet and Mongolian invaders. A plebiscite held in October 1945 confirmed the independence of the new People's Republic of Manchuria.

An intensive Desinicization program was enacted, imposing the Manchu language on the majority Chinese population with limited success[5], and the country provided support during the Korean War. During the 1960s, disagreements with Mao Zedong and Zhao Shangzhi over the latter's refusal to join the People's Republic were cited as a reason for the Sino-Soviet Split. In response for Chinese nuclear tests, Manchuria developed its own nuclear weapons, which it maintains to this day. After the fall of communism in 1991, Manchuria reformed its economy from a socialist economy to a mixed-market economy.

Although having the 15th largest economy in the world, the country has a lower GDP per capita compared to neighbors, compounded with government controversies. The economy is bolstered by new conglomerates that expanded after the fall of communism in Manchuria, propelling its rather high growth. It maintains amicable relations with most of its neighboring countries, and is a member of the United Nations, the G-25, the World Trade Organization, the Shanghai Co-Operation Organization, the World Bank, the Asian International Investment Bank, and the Asian Development Bank.

Etymology

The word Manchuria comes from the word Manju, decreed by Hong Taiji in 1636 to replace Jurchen, which was seen as derogatory. It may have come from the Buddhist deity Manjusri, or from a compound word meaning 'strong arrow'.

The current English name of Manchuria is rooted in controversy. It was first used by Japanese and Western geographers during the 18th and 19th centuries. [6] The Manchus reportedly have no native name for the land, except to refer to the territory as the Three Eastern Provinces (Dergi Ilan Goro).[7][8][9] Also, the Qing Dynasty consistently refer to their territory as merely China. It was during and after World War II that the word Manchuria gained currency, and was accepted as the normal English name of the country.

A few Western academics suggested renaming the English name of the country due to its associations with imperialism; the Chief Executive of Manchuria replied in 2013 interview with BBC: "This is telling a person that he needs to change his name because it was offensive, even if for that person it is harmless. It is bullying, pure and simple." [10]

History

Early History

Ancient Manchuria had been home for several ethnic groups such as the Evenki, the Nanai, the Ulchs, the Khitans, and the Jurchens. During various points in Manchu history, several Chinese dynasties controlled portions of Manchuria, usually in the coasts, and the Chinese also set up tributary relations with the tribes. The Korean kingdoms of Goguryeo, Gojoseon, and Buyeo also controlled parts of Manchuria. Finnish scientist Juha Janhunen also claimed that the Korean kingdoms might have substantial Tungusic-speaking minorities and even have an Tungusic elite. [11]

Within the 10th to 11th century, the Khitans of Inner Mongolia and Manchuria forged a state called the Liao, controlling Northern China and Manchuria, forcing the ancestors of the Jurchens into tributary status. The Khitan empire were the first state to control the entire modern region of Manchuria. [12][13]

Medieval History

By the early 12th century, the Jurchens, one of the tributary peoples of the Khitans rebelled against Liao rule and replaced them with the Jin Dynasty. Numerous campaigns against the Song Chinese enabled the Jurchen to capture territory in northern China. The Jurchens were then conquered in turn by the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty. During Mongolian rule, Manchuria was named as Liaoyang along with Northern Korea.[14]In 1375, Naghachu, a Mongolian Yuan official in Liaoyang, attempted to conquer the rest of the Ming-held Liaodong peninsula, but the Ming defeated his forces and surrendered. The Ming Emperor Yongle consolidated control of the Manchurian lands, creating the Nurgan Regional Military Commission.[15]

Chafing from Ming control, the Jianzhou Jurchens under Nurhaci started to consolidate their control of the region starting in the 1580s. They had to contend with the Evenki-Daur alliance led by Bombogor, finally killing him in 1640 and incorporating his remaining troops to the Eight Banners, a new Jurchen military organization.[16] During this period, Chinese cultural influence seeped through the Manchurian region and various ethnic groups living there.[17]

In 1634, Hong Taiji renamed the Jurchens into Manchus, citing the former name as now derogatory.

In 1644, the Ming dynasty was overthrown by peasant rebels. Ming general Wu Sangui called the Manchu leadership to assist in seizing Beijing. Using the opportunity of the chaos, the Manchus overthrew the nascent Shun Dynasty and established the Qing Dynasty. It was estimated that twenty-five million people died as a result of the conquest. [18]

Qing Empire

After the Manchus conquered China, they built the Willow Palisade to control Chinese emigration to the ethnic Manchurian lands..[19] Only ethnic Manchurians and Chinese bannermen are allowed to settle in Giring and Sahaliyan Ula.

During their reign over China, the Manchurians called their state "Dulimbai Gurun" and considered their state to be China.[20][21][22] Their definition of China also included Manchuria, Tibet, and Mongolia as a whole, and the "Chinese language" also refered to Manchu and Mongolian. The Treaty of Nerchinsk stated that the Manchurian lands are considered part of China. [23]

During the Kangxi and Qianlong eras, Manchurian-ruled China was said to have experienced a golden age. However, many scholars dispute the idea, claiming that literary censorship and political supremacy of the Eight Banners actually hindered its promise. [24][25]

As the centuries passed by, Han Chinese both legally and illegally settled to Manchuria, as Manchu banner landlords wanted Chinese labor and pay rent for their land to grow grain. 500,000 hectares of land were cultivated by Han Chinese by the end of the eighteenth century and about 203,583 hectares of Banner-owned lands were inhabited by Han, about 80% in estimate. [26][27] Many of these Chinese settlers were from North China and were introduced to settle on the Liyoo river to restore the land to cultivation. [28] Farmlands were also created by illegal Chinese settlers along with tenants. [29] Although the Qing Emperor Hungli/Qianlong repeated issued edicts against Chinese settlement in Manchuria, he later tolerated them as many of the Chinese settlers were suffering from drought. [30] .[31] Chinese settlers even claimed land even from the Imperial estates. [32] To increase the revenue, the Daoguang Emperor even allowed sale of Banner land to Chinese settlers.[33] Sinicization was accelerated that eighty percent of the population were Chinese.[34]

Penetration of Russian influence increased in the early 19th century. After the humiliating loss of the Opium Wars, the Qing were forced to cede eastern parts of Manchuria to Russia in 1857 to 1860 during the Peking Convention. However, Russian-Qing disputes failed to end, as Russia in 1868 tried to expel Chinese prospectors around Vladivostok. Attempts by Russia to occupy Askold Island, supposedly ceded but remained occupied by Chinese, only bore fruit in 1892 when they finally managed to retake the island.[35][36]

In the 1860s, the Qing were beset by weakened economic power, and half-hearted reforms such as the Self-Strengthening Movement failed to address the decline. Foreign companies such as the Swire Group and Jardines of the United Kingdom, based in Hong Kong, set up offices in Manchurian cities for trade purposes. From its opening in 1865 to 1891, Manchuria exported soybeans, soybean oil, wild silk, and ginseng. It imported in turn opium, cotton, and consumer goods. Girin Machinery Bureau, constructed in 1882, was the first factory built in Manchuria. It went on to become a machine shop during Japanese rule for Mantetsu rule and a coinage during the communist era.[4]

In 1896, Tsarist Russia obtained the privilege of building a railway in Manchuria through the "Sino-Russian Treaty", and in 1898 obtained a lease in Port Arthur (now Tiyeliyan). During this period Japan also gradually strengthened its expansion to Manchuria. In 1904, the Russo-Japanese War broke out and Russia was defeated and forced cede its sphere of influence to Japan. Since then, Japan, Russia and China have all accelerated the development of Manchuria. In 1907, the Qing court converted the Manchurian territories into full provinces. Japan established the South Manchuria Railway Company in 1906 to implement a colonial strategy in Manchuria and encouraged Korean immigration. In 1909, Japan gave back to China Yeonbyeon in exchange for concessions. [37]

An outbreak of bubonic plague occured in Manchuria in 1910-11, killing about 50,000 to 60,000 people in Harbin alone. [38] While the plague was contained, the high number of deaths forced Chinese and Manchurian officials to initiate stricter health measures, and shortly after the overthrow of the Qing, the North Manchurian Plague Office was established to combat outbreaks.

Fengtian Era

After Yuan Shikai's death in 1916, Zhang Zuolin took over the administration of the Manchurian lands. In 1920, he then set reforms that enabled Manchuria, then known as the Three Eastern Provinces, to be relatively unscathed by the chaos of the warlord era in China. Although Manchuria remained officially a part of China, it was effectively isolated from China and protected by Zhang's Fengtian Army, and its naval and air forces are considered advanced compared to the other Chinese states. He tolerated the Japanese presence in Manchuria but is said to be losing patience at their control of Kwantung and the South Manchurian railroad.

Zhang Zuolin was later killed in the Huanggutun Incident on 2 June 1928, allegedly on the orders of the Kwantung Army due to the latter perceiving him as a traitor. Zhang Xueliang took his place, then allied himself with the advancing Kuomintang to prevent conquest.

A month after the reunification with the KMT, Zhang attempted to establish control over the Chinese Eastern Railway causing a armed skirmish with the Soviet Union. Zhang was now the de facto dictator of Manchuria, although he remained officially loyal to the Kuomintang supporting the nationalist government in the Central Plains War. However Chinese-Japanese relations were quickly deteriorating with Japan trying to exert more influence in Manchuria.

Manchukuo

In 1931, the Japanese forces in Manchuria seized the country from the Chinese, creating a satellite state called Manchukuo a year later. The Japanese installed Pu Yi as a figurehead leader while real power is in the hands of the Japanese advisers. Several anti-Japanese Manchurian commanders such as Tong Linge (Tunggiya Linge) joined Kuomintang forces in China, with several of them being killed in the Second Sino-Japanese War. [39][40][41] Manchuria was used as a buffer state between Japan and the Soviet Union as both countries clashed twice in 1938 and 1939. [42] It was said that Japanese control of the resources in Manchuria enabled it to execute the Pearl Harbor bombing and initate a conquest of Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific. [43]

Several anti-Japanse Manchu leaders like Joogiya Šangjy, Foimo Hanjang, and Yang Gingioi fled to the Soviet Union and Mongolia and established a government in exile. A rift between Joogiya Šangjy and the Yanan leadership was only temporarily healed and Joogiya decided to separate and rename his Northeast Anti-Japanese Army into the Manchurian People's Army and finally advocate a separate Manchurian communist state to "defend itself from Kuomintang" machination. A large number of former Northeast Anti-Japanese Army soldiers are of ethnic Manchu descent and Joogiya who was mixed Chinese and Manchu wanted an "ethnic revival" of the Manchus and thus ordered Manchu-language education.

A coup by secretly communist Manchukuo officers during the Soviet invasion of Manchuria declared the establishment of the Manchu Republic. This was led by Zhang Xueming, Zhang Xueliang's brother, who secretly fled from Mainland China, and used the flag of the Fengtian Clique. However, in September 1, 1945, he had to cede power to Joogiya Šangjy, who secretly promised that Manchuria would never be sold out to either Chiang or Mao, in exchange of Xueming returning to China. The Kwantung Army, already battered by the atomic bombing of Japan, surrendered in droves. [44][45][46][47]Pu Yi escaped to Japan, but was captured by the Americans and made witness to the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal. He was imprisoned by the Soviet Union until released to live his exile to Japan.[48] The majority of the Japanese settlers were either deported back to Japan or were kept as "hostages" by Joogiya Šangjy to elicit Japanese goodwill. Many of them only were able to return in the 1960s. [49]

Manchu People's Republic

During the final days of World War II, the Soviet Army in the Far East attacked Manchuria and together with the Mongolian People's Army and the Manchurian People's Army, and occupied the former state of Manchukuo. It was said that the Chinese refusal to hand over Inner Mongolia to the Mongolian People's Republic spurred the Mongolian dictator Choibalsan to declare that the former Manchukuo should be handed over to Joogiya's government in exile. Chiang Kai-shek replied that both Mongolia and Manchuria should remain under Chinese control, which angered Joogiya. Tensions flared, the Nationalist and Communist Chinese were prohibited by the MPA and Mongolian forces from occupying the former Manchukuo. .[50]With the former Manchukuo Army soldiers being integrated to the Manchurian People's Army, Manchuria declared independence in February 1, 1946.

In exchange of recognizing independence, the main Chinese Communist Party forced Manchuria to accept Guwalgiya Siyanging, an ethnic Manchurian, as President, as well as Gao Gang as Chinese ambassador, in exchange of independence. However, Guwalgiya died in 1947, and Gao Gang had at point had eased himself with the main Manchu leadership headed by Joogiya Šangjy and Jeo Baojung as figurehead President.

During the Korean War, Manchuria entered the war on the side of North Korea along with the People's Republic. A "People's Support Army" was sent by Manchuria alongside China's "People's Volunteer Army". Joogiya reluctantly entered the war to both secure his southern border and to prevent China from occupying it as a pretext for inaction. 83,400 Manchurians were killed in action among 300,000 Manchurian soldiers who fought in the "War to Aid Korea and Resist America."

However, the high cost of the war and the defeat of North Korea had angered many Manchurian officials, and Joogiya Joogiya once considered resignation; he was retained at the request of the communist party. Yang Gingioi and Jeo Baojung were removed for disagreeing with Joogiya about the conduct of the war; Joogiya formally became president in 1956. They both left for China, never returning to Manchuria again. Jeo Baojung later became governor of Yunnan, while Yang Gingioi went back to Yenan province, quietly dying in 1965.

Joogiya initiated the so-called "Sahaliyan Ula Protocol" in 1960, as a response to China's more aggressive stances. It aims to usurp China's place as the leading Asian communist power by using internal reform within party and government, publicly allying with the Soviet Union but at the same time maintaining its independence, and with prime minister Sheng Shicai, broadened their relations with the West. Thousands of pro-unification PRC Manchurians were jailed or executed. Joogiya while publicly reforming the internal structure of the government, remained powerful. Unlike his neighbors, however, Joogiya remained comparatively "moderate".

In 1956, Manchuria started a nuclear program, intended at first for peaceful purposes. However, the government believed that Manchuria would also need to use the nuclear program to create atomic weapons. Soviet documents revealed that the rationale is to prevent both American and Chinese aggression. Seeing Manchuria as too big for the Soviet Union to be brought into heel, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev tacitly allowed Manchuria to develop its own nuclear weapon, who is suffering with the fallout from Mao Zedong during the Sino-Soviet Split. Soviet scientists helped Manchurian scientists in the development of nuclear weapons, detonating it in 1972 with widespread condemnation. This encouraged the USSR to tacitly allow most Warsaw Pact countries with the specific exception of East Germany to develop their own arsenal; East Germany later procured their own arsenal and was inherited and kept by the present unified government of Germany.

In 1970, Joogiya Joogiya died, replaced by Foimo Hanjang as President and Sakda Cunrun (Li Chunrun), Joogiya's preferred successor, as General Secretary. Sakda had to inherit the worsening border clashes within China due to the Cultural Revolution; already, Joogiya was denounced in China for his failure to incorporate Manchuria to the PRC. Red Guards trying to infiltrate Manchuria were "killed on the spot". Soviet forces in Tiyeliyan and the Chinese-Manchurian border also engaged in border clashes. [51]

Of all the Soviet satellite states, Manchuria was one of the few that actually requested for Soviet and Eastern Bloc immigrants to upset the balance of the still-Chinese majority population. About 2 million immigrants from the Eastern Bloc emigrated to Manchuria, while simultaneously encouraged Han Chinese emigration to the PRC in exchange of ethnic Manchurians by the PRC until the emigration stopped in 1961 due to fears that ethnic Chinese will emigrate back to Manchuria.

Manchuria was denied by the Republic of China from admission into the United Nations due to its claims, even though it acquiesced in its admission of Mongolia in 1961. .[52][53][54] (see China and the United Nations) In 1971, the People's Republic in an overture to improve Manchuria-China relations, approved of Manchuria's entry to the United Nations.

Modern Manchuria

By 1990, Manchuria's economy started to decline; many people felt that the communists have long outlasted them. Chinese exiles after the 1989 protests aided the pro-democracy protesters. After much hesitation, Ligiya Joolin resigned and a more moderate leader, Liu Binyan, took over.

After the fall of Communist regime in Manchuria, the government in Changchun feared that China will attempt to overthrow their government by force, as Chinese people who fled the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 were allowed refuge by the Manchurian government. Also the border clashes with Korea have put into question Manchuria's peaceful intentions. [55][56].

Government and Politics

Manchuria is officially a unitary semi-presidential parliamentary republic with a unicameral legislature.[57][58]The non-governmental organization Freedom House consider Manchuria as Partially Free.[59]

However, it can be said that Manchuria is technically both a republic and a monarchy; the constitution officially recognizes the chief of the Aisin Gioro family "as part of Manchuria's intangible heritage and a symbol of the state and the unity of the people";his official title is called the Founder (Yuwanjun) by the government. Even then, he is still unofficially referred to as the Emperor, and has similar role as his Japanese counterpart. The Founder performs the rituals for the state. It was said that this role was a replacement for the ranking of General Secretary of the Manchu Communist Party which is deemed the highest office during the Communist era, but today the Founder serves as figurehead. His official residence is the Salt Palace.

The President (Beliihitiyande) is the technical and actual head of state of the country; he is elected by the populace for a five-year term renewable only once in a re-election. He appoints the Prime Minister (Dorgi Yamun I Da) who heads the cabinet and the Legislative Assembly; he must be the leader of the party that receives the most votes in the house. The so-called "Joogiya's Mansion", the former Kwantung Army commander's mansion during the Manchukuo era, was converted for the President's use.

The Constitution of Manchuria serves as the supreme law of Manchuria, which established clear separation of powers. However, for the most part of its history Manchuria was under autocratic rule. From 1945 Manchuria was ruled as a Communist single-party state that ended in 1991 following the Sorghum Revolution. In 1990 Manchuria adopted its current constitution, becoming a liberal democracy. Nevertheless former members of the Communist Party of Manchuria are still prominent and active in politics.

Foreign Relations

Manchuria's foreign affairs is conducted by its Foreign Ministry. Its key foreign policy is to retain its relative military power among other Asian nations, especially that along with China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, possess nuclear weapons in the Eastern Asia region. It pursues an independent foreign policy but has been notably close to Russia since 1945. However, Manchuria also pursued warmer relations with Western countries particularly the United States.

Manchuria is a member of several organisations such as the United Nations, G-20, WTO, APEC, IMF, WBG, ADB, East Asia Summit, ACD, PEMSEA, Non-Aligned Movement, Group of 15, and the Group of 24.

During the Cold War, it traditionally supported the Soviet Union until its demise in 1991. During the Manchukuo era, the Soviets opened consulates in Harbin. After the war, the Soviet Union upgraded their full relations with the new Manchurian communist government. Manchuria continues its relations with Russia amicably, and is viewed as Manchuria's traditional ally, and a special relationship with Russia emerged. [60][61][62][63] Manchuria has a neutral position on the Crimea problem, insisting that all problems should be solved by peaceful means if possible. Manchuria has amicable relations with all the other post-Soviet republics, especially Kazakhstan and Uyghuristan.

Manchuria also has traditionally warm relations with India, as Manchuria provided material for India's nuclear weapons program.[64]

As Mongolia second-largest trading partner, Manchuria enjoy excellent relations with its western neighbor. There are issues being tackled including emigration of Mongols to Manchuria.[65]

Manchuria's relations with the West increased considerably. There is steady immigration to the United States, but as these emigrants tend to be Chinese-speaking Manchurians, until recently they are considered as Chinese.

It was with its immediate neighbors that Manchuria has difficulty in maintaining good relations. Mao's acceptance of Manchurian independence was said by him to have been made with "great reluctance." Even though Manchuria and China fought on the same side with North Korea during the Korean War, China tried and failed to use the war as leverage to re-incorporate Manchuria. During the Sino-Soviet Split and the Cultural Revolution, Manchuria had to fend off border incursions by China with Soviet help. Only after the Sino-Vietnamese War and China's market reforms did Manchuria-Chinese relations improve, and even then, the Second Korean Conflict and the fall of the communist regime in Pyongyang was "never forgotten" by Beijing and Manchuria's role with it was used as a sticking point.

Manchurian-Korean relations are friendly despite the Second Korean War. Sticking points include the necessity of sending reparations to Korea and claims by Manchurian historians that Korea deliberatedly whitewashed the history of Goguryeo to erase the Manchurian origin of the kingdom, causing protests and counter-protests from both sides.[66][67] [68]. As of 2018, Manchuria is now Korea's largest trading partner, accounting for 46 percent of the trade.[69]

While Manchurian-Japanese relations are now better than before, their background was also complex. Manchurian politicians occasionally request compensation from Japan, in which Japan said it already made apologies. Japanese politicians in turn decry Manchuria's sidestepping in its roles in anti-Japanese pogroms in 1946. Nevertheless, Japanese-Manchurian relations are cordial and compared in the past, now done in an equal basis; anime and manga are regularly being shown in Manchuria with a large fandom in Manchuria itself, and Manchurian light novels and visual novels recently provide material for new Japanese animated series. Many Japanese people retire to Manchuria and younger Manchurians emigrate to Japan. Manchuria's embassy in Japan was still the one used by the former Manchukuo regime. 30% of the Chinese diaspora in Japan are of Manchurian origin.[70]

Military

The Manchurian Armed Forces is the second largest armed forces after China.

The Armed Forces is composed an army, navy, and air force. The MAF has the second largest army in East Asia in active forces (1,228,300), though its paramilitary forces called the Green Standard Corps (9,320,000) when added make it the largest military force in the world.[71][72] Manchuria has the largest special force and submarine force in the world. [73]

In addition, a separate armed force called the Banner Guard Corps directly reports to the Founder, and serves as his bodyguard. The Banner Guard Corps is focused on unconventional warfare.

The President of Manchuria is the commander-in-chief of the MAF, which answers to the Ministry of Defence. The Chief of Staff of the Manchurian Armed Forces is a professional soldier with a four-star rank. The military's influence in civilian life had been shaped by its role by throwing its support behind the protesters in the 1991 anti-communist revolution. [74]

The predecessor to the MAF, the Manchurian People's Army, primarily received military equipment from the Soviet Union. The MAF's foreign weaponry are largely Soviet or Eastern Bloc in design if not in manufacture, and many of the weaponry made in Manchuria are of East Bloc heritage as well. Recently Manchuria has started purchasing weaponry and equipment from Germany and Japan. [75]

Manchuria possesses nuclear weapons. [76][77] The nuclear weapons program were built in the 1960s as an anti-Chinese deterrent, and after the fall of the Soviet Union, it was rumored that the Soviets actually sold some of their newer weapons to Manchuria in exchange not to sell Manchurian weapons to countries Russia disapproved of. Manchuria signed the Nuclear Proliferation Treaty in a new revised form; it also signed the Chemical Weapons Convention in 1987.[78][79]

Patriotic Civil Service is the term called for conscription; all males at the age of 18 are considered recruits; people who had disabilities are granted honorary ranks but are only allowed to participate in civil relations. Refusal to serve is considered a capital punishment during early communist times which meant automatic death penalty; this was reduced and concentious objectors are sentenced to hard labor camps, which were still criticized. After the fall of the Communist system, conscientious objection is no longer punished; "equivalent civilian work" or heavier taxation were used instead.

Internal security is provided by the Giyarici.

Geography

The territory within Manchuria lies within the northern part of the North China craton, which is an area of Precambrian rocks over 100 million hectares. Manchuria is traditionally divided into three geographic regions: the Hingan mountains, the Manchurian plain, and the Golmin Shanggiyan Mountain region. The Hinggan mountains are a Jurassic mountain range[80], stemming from a collision between the North China craton and the Siberian craton.

Manchuria was never glaciated during the Quartenary period, but the fertile soils of the lower-lying areas indicate movements from the western mountains in Asia such as the Himalayas and the Tien Shan mountains, and also the Gobi and Taklamakan deserts.[81]

In the middle between the Hinggan Range and the Golmin Sanggiyan Mountains is the Manchurian plain, also known as the Dongbei plain in Chinese or the Sungari-Liyoo Plain, with the Sungari, Non, and Liyoo Rivers running through the plain. Here is the area where widespread cultivation takes place. Majority of the soybean, millet, wheat, and rice are being planted in this region. The area is connected to the North China plain to the south-west.

Climate

Manchuria's climate provided contrasts, with very Arctic-like winters and hot, tropical summers. The position of Manchuria between the Eurasian landmass and the Pacific Ocean contribute to this climactic situation. Due to being in the border region of Eurasia and the Pacific, the climate triggers monsoonal wind reversal.

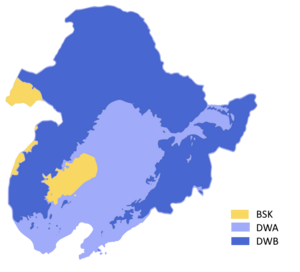

The dominant climate type according the Koppen scheme is the hot-summer dry continental, especially in the plain. In the far north, dry-winter subarctic climate prevails, and in the west, pockets of cold semiarid climate persist. [82]

Temperatures during the winter are usually cold due to the Siberian High, ranging from -5 °C (23°F) to -30°C (-22°F), depending on latitude, which is considered colder when further north. [83] The Siberian winds are relatively dry, however, and the snow is rarely heavy. [84] Thus Manchuria, despite being colder than North America, never glaciated due to the strong westerly winds from western Eurasia. [85]

In contrast, during summer, moist, southwestern winds bring thunderstorms, usually bringing 400 to 1150 mm of rain depending on the area; the area around the east receives more rain.

Administative Divisions

Manchuria is organized into provinces (golo, голо), subdivided into leagues (culgan, чулган), banners (guusa, гөса) and towns (sumu, суму). Leagues only exist for legislative purposes. Certain cities such as the capital Cangcon, Halbin, Mukden, and Tiyeliyan having provincial status, but lack the league divisions and is treated as one level. Instead of banners and towns, cities with provincial status have wards and districts on their stead.

| # | Name | Administrative Seat |

Manchu | Chinese | Population | Area (km2) |

Flag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Huleigiolo | Hailar | Hулеигиоло;

ᡭᡠᠯᡝᡳᡤᡳᠣᠯᠣ |

呼伦贝尔;Hūlúnbèi'ěr | 2,549,278 | 263,953 | |

| 2 | Sahaliyan Ula | Aigun | Сахалиян Ула;ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ ᡠᠯᠠ | 黑龙江;Hēilóngjiāng | 2,623,541 | 10,414.94 | |

| 3 | Liyoo Ning | Išangga Gašan | Лиёо Нин ᠯᡳᠶᠣᠣ ᠨ᠋ᡳᠩ |

辽宁;Liáoníng | 3,044,641 | 19,698.00 | |

| 4 | Halhuun Ula | Erdemu be Aliha | Халхун Ула ᡭᠠᠯᡥᡡᠨ ᡡᠯᠠ |

熱河;Rèhé | 1,819,339 | 10,354.99 | |

| 5 | Girin | Girin Ula | Гирин ᡤᡳᡵᡳᠨ | 吉林;Jílín | 8,106,171 | 12,860.00 | |

| 6 | Hinggan | Jerim | Хинган ᡥᡳᠩᡤᠠᠨ | 興安;Xīng'ān | 1,858,768 | 4,743.24 | |

| 7 | Yeonbyeon | Yongil | Янбиян ᠶᠠᠨᠪᡳᠠᠨ | 延边; | 2,271,600 | 43,509 | |

| 8 | Tiyeliyan | Tiyeliyan | Тиелиян ᡨᡳᠶᡝᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ | 1,392,493 | 6,690,432 | ||

| 9 | Niyengniyeltu | Cangcon | Ниыенгниыелту

ᠨᡳᠶᡝᠩᠨᡳᠶᡝᠯᡨᡠ |

6,690,432 | 12,573.85 | ||

| 10 | Nemeri Ula | Cicigar | Немери Ула

ᠨᡝᠮᡝᡵᡳ ᡠᠯᠠ |

2,444,697 | 67,034 | ||

| 11 | Acan Ula | Giyamusi | Ачан Ула ᠴᠠᠨ ᡠᠯᠠ |

1,709,538 | 62,482 | ||

| 12 | Mukden | Mukden | Мукден ᠮᡠᡴᡩᡝᠨ |

2,138,090 | 11,272.00 | ||

| 13 | Liyoo Dergi | Hetu Ala | Лиёо Дерги

ᠯᡳᠶᠣᠣ ᡩᡝᡵᡤᡳ |

10,007,000 | 68,303 | ||

| 14 | Halbin | Halbin | Халбин ᡥᠠᠯᠪᡳᠨ |

3,386,325 | 14,382.34 | File:Flag of the City of Harbin.svg |

Cities with urban area over one million in population

- Independent cities in bold.

| # | City | Urban area[86] | District area[86] | City proper[87] | Prov. | Census date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mukden | 5,718,232 | 6,255,921 | 8,106,171 | MK | 2010-11-01 |

| 2 | Halbin | 4,933,054 | 5,878,939 | 10,635,971 | HL | 2010-11-01 |

| 3 | Tiyeliyan | 3,902,467 | 4,087,733 | 6,690,432 | TY | 2010-11-01 |

| 4 | Cangcon | 3,411,209 | 4,193,073 | 7,674,439 | CC | 2010-11-01 |

| 5 | Engemer Alin | 1,504,996 | 1,544,084 | 3,645,884 | LN | 2010-11-01 |

| 6 | Girin | 1,469,722 | 1,975,121 | 4,413,157 | GR | 2010-11-01 |

| 7 | Sarhu | 1,433,698 | 1,649,825 | 2,904,532 | SU | 2010-11-01 |

| 8 | Hetu Ala | 1,318,808 | 1,431,014 | 2,138,090 | LN | 2010-11-01 |

| 9 | Cicigar | 1,314,720 | 1,553,788 | 5,367,003 | SU | 2010-11-01 |

| 10 | Bengsi | 1,000,128 | 1,094,294 | 1,709,538 | LN | 2010-11-01 |

Economy

Manchuria has a economy that is measured to be the 15th largest in the world by 2018, at US$989 billion. Manchuria has been one of the strongest in the Asia-Pacific region and is considered an honorary Asian Tiger. The service industry is smaller compared to the other East Asian countries. Manchuria was the richest East Bloc country in Asia and was second only to Japan.[88][89]Even after the fall of communism, Manchuria is the richest former communist country when measured by its GDP per capita.

During the Qing period, Manchuria was one of the most industrialized parts of the Chinese Empire, and its coal deposits made it a highly-urbanized country. During the Manchukuo era until 1945, Manchuria was considered more industrialized than China and even Japan; Japanese investment has expanded Manchukuo industries.[90][91][92] Indeed, China refers to Manchuria as the "Eldest Son" of industrialized communist countries in Asia. After the fall of communism, Manchuria struggled to keep its industry as it stagnated, prompting the government to diversify its economic structure.[93]

In 1991, Manchuria's GDP shrunk in 1993 to the level it achieved in 1976, and considered a "national scandal". President Tiyan Fengsan of the People's Party then installed new economic policies and copied the economic system instituted by Japan in the 1950s and South Korea in the 1960s. Instead of privatization of state-owned companies, Tiyan encouraged businessmen to set up their own businesses to augment the economy. Manchuria managed to keep the majority of its labor-intensive manufacturing from being transferred to the neighboring PRC keeping unemployment at bay, although pay was low compared to Korea. There are calls for the government to abandon state-owned enterprises altogether as they are a remnant of communist and Manchukuo era policies.[94]It was said that Manchuria's explosive economic growth after the Financial Crisis was due to Tiyan's reforms; however, inequality in income increased. It's petroleum and shale oil industry, enabled Manchuria to increase its economic clout; also, its economic penetration to Eastern European markets and West Asian markets had been credited to Manchuria's rise as one of the world's largest economies.

Manchuria's economy still remains industrial, with steel, automotive, rail, aircraft, and shipbuilding industry predominating. Manchuria also has coal and petroleum industry and has several petroleum refinery facilities. The appliance industry has also been booming since the 2010s, and Manchuria's software production has been ramped up since 2005.

Despite decline of agriculture due to industrialization, it remains important. Fishing is important on the coasts and rivers, while farming is dominant in the south with corn, wheat, soya, and sorghum commonly cultivated there. Animal husbandry is also common, with cattle, pigs, horses, and sheep being raised.

Agriculture

Agriculture still plays a vital role in the Manchurian economy.[95] In the northern cold regions, corn, wheat, sorghum, flax, potatoes and sunflowers are grown. In the center, soybeans are planted; Manchuria is the chief source for US soybean.[96] In the east, rice is grown especially in Yanbiyan, whereas in the south, corn, sorghum, cotton, and soybeans are cultivated. The south is also where Manchuria's fruit industry dominate. Herding is also common, with pigs, cows, and horses predominating; the dairy industry also supplies all of Manchuria's yearly needs. Sheep farming is common in Baicheng.

Manchuria's agriculture has undergone a shift after 1990. Prior to 1990, all farming are done within collective farms confiscated from the Manchukuo government and Japanese companies, with 50 families inhabiting a farm called Concentrated Agricultural Farm. The collective farms have moderate to high production rates but needed subsidies for technology. In 1990 collective farms remain but as their subsidies were cut off, many failed and shuttered. Conversion to co-operative farms alleviated the situation. Private plots, de-facto recognized by 1971, were legalized by 1990.

Currency

The currency is known as the Jiha, divided into 100 Menggun. It is issued by the Manchurian Central Bank. Manchuria copied Singapore's example of allowing its exchange rate to fluctuate within an undisclosed trading band.[97]

Industry

Manchuria's industry has developed considerably, both light and heavy industrial products. In the late 1990s, Manchuria attempted to curry foreign investment, including those of Korea, China, and Japan, and Western countries, and there was a boom in manufacturing, however, Russian and East European industries took up the bulk of foreign investment. However, it is still a major production base for heavy industry. Many companies have origins in the Manchukuo era and nationalized by communists; the saying that "Manchuria X Corporation" owns everything in Manchuria is still evident, as these state-owned industries control 25 percent of the economy. Others are dominated by so-called "Ulinhala" or "Wealth clans", analogous to the Zaibatsu/Keiretsu of Japan and the Chaebol of Korea.

In 2012, President Liyoo Siaobo initated the Revitalize Manchuria program to enhance the industrial situation in the country.[98] While it saw moderate success, Liyoo's untimely death and political infighting hampered its implementation.[99] In addition, remnants of the old communist bureaucracy was still largely in charge of Manchuria's economy, prompting government leaders to encourage private enterpeneurships without government spurring.

There are three industrial zones in Manchuria: Mukden-Tiyeliyan Industrial Zone, Cangcon-Girin Industrial Zone, and Halbin-Sartu Industrial Zone. Two major urban agglomerations have been formed: the central and southern Liaoning urban agglomeration and the Hachang urban agglomeration. The main industrial cities are Mukden, Tiyeliyan ,Engemer Alin, Bensi, Fusi Hecen, Girin, Cangcon, and Halbin.

Transportation

Transportation in Northeast China is dominated by railways, with roads coming in second and air and sea transport not falling behind.

Railway network

Manchuria's railways, owned by the Manchurian National Railway, are one of the world's busiest. High-speed rail in Manchuria is common; as the matter of fact, the first railway system to be called "high-speed" was created during the Manchukuo era.

The late Qing's Dong Qing Railway and the South Manchurian Railway constitute the "D" word Manchurian Railway. While serving Russian and Japanese interests, it also promoted the development of the country. Harbin, as the intersection of two railways, replaced Qiqihar and became the major city in North. During the Manchukuo era, the Japanese expanded the railway network, which is not much different from the current form.

In recent years, high-speed railway lines such as the Qingdao-Liyooning Passenger Railway, the Hal-Tiyelian High-speed Railway, the CangGirin InterCity, the HaJi Railway, and the MukDan Railway have also been completed and opened to traffic.

Highway

Manchuria has an extensive highway system. The Tiyeliyan-Mukden Superhighway was opened in 1990, shortly before the fall of the Communist regime. [100]

Shipping

Manchuria's major port is Tiyeliyan, with Huludao as second. Tiyeliyan's port handles the bulk of shipping in Manchuria.[101]During 1973, Tiyeliyan handled 23.1 million tonnes.[102]By 2015, this now stands to 555 million tonnes.[103]Tiyeliyan is the world's seventeenth-largest port in 2012. [104]

Aviation

There are currently 22 major civil airports, including international airports: Mukden International Airport[105], Halbin International Airport, Ice Hoton New International Airport, Tiyeliyan International Airport, Hailar Airport, Yanji Airport, Mudanbira Airport, Yingkou Airport, Dandong Airport and Giyamusi Airport. The first four airports have flights globally, while the rest are concentrated on neighboring Asian countries. The Ilan-Ula (Sanjiang) Plain is has many airports. Manchurian Airlines[106][107][108] has been the flag carrier of Manchuria since 1931.

Energy

The slim majority of Manchuria's energy resources are being based on fossil fuels; they have been replaced by nuclear energy and hydroelectric energy. Coal is being steadily replaced due to being used as shale oil for export. Manchuria also shies from using petroleum as fuel for power plants, preferring it to be used as fuel for vehicles and petrochemicals instead. Renewable energy like solar and wind power had been limited due to lack of funds and overabundance of energy supply.

Demographics

Languages

The official language is the Manchu language, which came to mean both the Tungusic Manchu-Sibe language and the Mandarin Chinese spoken in Manchuria. The de-sinicization efforts had ensured that Manchu would be spoken as a first language by 64% of the population. The near-exclusive use of Manchu in the military and the government, mandated in the communist era, which employed universal conscription was cited as a reason in the Manchu-language revival. Manchu-Sibe as it was called is written in the Cyrillic script introduced in 1949, although the older vertical traditional Manchu script is being slowly re-introduced.[109][110][111] Manchurians also conduct free language sessions throughout the country to make the Manchurian people proficient in the language, and there are even Manchu language classes in neighboring China.[112][113][114][115]It was said that the communist government deliberately revived the Manchu language to differentiate itself from China and to reduce illiteracy among the population.

Other languages are Korean, spoken in Yeonbyeon, Japanese in Tiyeliyan and isolated southern communities, Mongolian, Orochon, and Daur in the west, and Russian in the border areas and in Halbin.

Ethnic Groups

Ethnicity in Manchuria (Manchuria Statistics Office 2014)

Religion

Ethnicity in Manchuria (Manchuria Statistics Office 2014)

Fertility Rate

Manchuria has the lowest fertility rate in the world.[116] It was estimated that in 2015, Manchuria's fertility rate was 0.55 percent, even lower than Japan, which already have a low fertility rate.

Society and Culture

Education

Manchuria inherited from Manchukuo and Communist times an efficient educational system.[117] Manchuria's government had established numerous universities and schools. City universities tend to be of better quality than provincial schools, a problem acknowledged by the government.[118] Literacy rates have been on an all-time high of 98.5 percent, with most illiteracy coming from the western rural areas of Manchuria.

Manchuria's education system is divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary education. Facilities are either maintained by both private and public schools under the Ministry of Education. The ministry also sets a National Curriculum that provides guidelines for teachers; it is always regularly updated. Private schools may adopt a modified version of the National Curriculum provided it did not conflict with the government's policies.

All education is compulsory in primary and secondary. Subsidies remain for these schools; most tertiary school subsidies ceased after the fall of the communist regime.

Prior to formal education, children are educated in kindergartens. By the time they reached five, they are enrolled in primary schools until the age of eleven. In elementary school, the children by learning Manchu-Sibe, Chinese, mathematics, science and physical education.

Manchurian schools usually conduct school festivals, a trait inherited from the Manchukuo and communist eras. [119]

Like its fellow East Asian countries, Manchuria's education system has been criticized due to pressures given to its students and also due to being behind its neighbors, even China's. Rote memorization are also seen as problems.

Culture

Manchurian culture is a mix of traditional Manchu culture, Manchurian Chinese influences, and input from its neighbors and conquerors.

Cuisine

Manchurian cuisine (Manju sogi) is a amalgamation of ethnic Manchu, Chinese, Korean, Mongolian, and European influences. They are often hearty, with meats being roasted and seasoned with cumin and garlic and salt. The Man-Han Imperial Feast was known in Asia as a court dish during Qing times, modified in the present-day to suit modern tastes and only using domesticated meat. [120]

Manchurian cuisine is concentrated on grains, vegetables, and meat. Wheat, sorghum, soybean, and rice are commonly used as staple grains, with potatoes and corn becoming common in the late 20th century. Gidaha Lafu, or Suancai in Chinese, is fermented cabbage similar but not identical to the Korean Kimchi, and is commonly used in dishes. Bairou Xuechang is a famous pork and cabbage dish, as well as ludagun.

Sport

Manchuria's national sports are said to be ice hockey, football, basketball, and the indigenously developed sport of Pearlball.

Manchuria's football association is founded during the Manchukuo era.[121] While it is a competitive team in the Asian championships, it was only able to enter the FIFA World Cup twice in 1966 and in 2010, in the latter's case defeating Cote d'Ivoire's national football team but in turn defeated by both Portugal and Brazil.

Manchuria was supposed to compete in the Summer Olympics in 1932, but its only candidate, Liu Changchun, defected to the Republic of China and became the first Chinese Olympic representative. Attempts to join the 1936 Olympics in Berlin were frustrated by the International Olympic Committee's decision not to allow unrecognized states in the Olympics. Manchuria was to join the 1940 Summer Olympics but World War II prevented its entry[122] Instead, it sent atheltes to the 1940 Far East Games organized by Japan. [123] It was only able to compete in 1952 in Helsinki due to Finnish invitation, and as the Manchurian-Chinese delegation at the insistence of the Republic of China. By 1956, it was able to compete under its own name since. Manchuria is more successful in Winter Games, primarily due to the country's climate.

References

Citations

- ↑ Fengtien Clique; Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (1970-1979).

- ↑ Byington, Mark E. (2016). The Ancient State of Puyŏ in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 11, 13. ISBN 978-0-674-73719-8.

- ↑ Tamang, Jyoti Prakash (2016-08-05). Ethnic Fermented Foods and Alcoholic Beverages of Asia. Springer. ISBN 9788132228004.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Son, Chang-Hee (2000). Haan (han, Han) of Minjung Theology and Han (han, Han) of Han Philosophy: In the Paradigm of Process Philisophy and Metaphysics of Relatedness. University Press of America. ISBN 9780761818601. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, Volumes 11–12, 1867, p. 162

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ [1]Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ [2]Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ "Seven decades of bitterness". BBC News. 2014-02-13. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 03: "Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part 1," at 32, 33.

- ↑ Ruins of Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands By Mark Hudson

- ↑ Ledyard, 1983, 323

- ↑ Patricia Ann Berger – Empire of emptiness: Buddhist art and political authority in Qing China, p.25

- ↑ Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2002). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0520234246.

- ↑ Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2002). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0520234246.

- ↑ Forsyth 1994, p. 214.

- ↑ "5 Of The 10 Deadliest Wars Began In China". Business Insider. 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 3 (2000): 603–46.

- ↑ Hauer 2007, p. 117.

- ↑ Dvořák 1895, p. 80.

- ↑ Wu 1995, p. 102.

- ↑ Zhao 2006, pp. 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14.

- ↑ 刘小萌 (2008年). 《清代八旗子弟》. 辽宁民族出版社. p. 第206页.

- ↑ 周敏(鲁东大学历史与社会学院) (2008年). 《首崇满洲——清朝的民族本位思想》. 《沧桑》.

- ↑ Richards 2003, p. 141.

- ↑ Richards, John F. (2003), The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World, University of California Press, p. 141, ISBN 978-0-520-23075-0

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 504.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 505.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson, James (2000). "Land Use and Society in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia During the Qing Dynasty". Environmental History. 5 (4): 503–509. doi:10.2307/3985584. JSTOR 3985584.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ↑ Scharping 1998, p. 18.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 507.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 509.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 509.

- ↑ Template:Harvcoltxt

Probably the first clash between the Russians and Chinese occurred in 1868. It was called the Manza War, Manzovskaia voina. "Manzy" was the Russian name for the Chinese population in those years. In 1868, the local Russian government decided to close down goldfields near Vladivostok, in the Gulf of Peter the Great, where 1,000 Chinese were employed. The Chinese decided that they did not want to go back, and resisted. The first clash occurred when the Chinese were removed from Askold Island, in the Gulf of Peter the Great. They organized themselves and raided three Russian villages and two military posts. For the first time, this attempt to drive the Chinese out was unsuccessful.

- ↑ "An Abandoned Island in the Sea of Japan". 2011-01-25.

- ↑ https://www.economist.com/special-report/2007/03/31/history-wars

- ↑ "Memories of Dr. Wu Lien-teh, plague fighter". Yu-lin Wu (1995). World Scientific. p.68. ISBN 981-02-2287-4

- ↑ 李, 世峥 (1 September 2010). "基督徒将军佟麟阁:抗战殉国的第一位高级将领". 中国民族报. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ "佟麟阁中国抗日战争牺牲的第一位高级将领". 每日头条. 27 May 2017.

- ↑ "佟麟阁中国抗日战争牺牲的第一位高级将领". 每日头条. 27 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018.

- ↑ Coox, Alvin D. (1990). Nomonhan : Japan against Russia, 1939 (1st ed.). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. p. 841. ISBN 978-0804718356.

- ↑ Edward Behr, The Last Emperor, 1987, p. 202

- ↑ Robert Butow, Japan's Decision to Surrender, Stanford University Press, 1954 ISBN 978-0-8047-0460-1.

- ↑ Richard B. Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire, Penguin, 2001 ISBN 978-0-14-100146-3.

- ↑ Robert James Maddox, Hiroshima in History: The Myths of Revisionism, University of Missouri Press, 2007 ISBN 978-0-8262-1732-5.

- ↑ Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan, Belknap Press, 2006 ISBN 0-674-01693-9.

- ↑ Behr 1987, p. 285.

- ↑ Paul K. Maruyama, Escape from Manchuria (iUniverse, 2009) ISBN 978-1-4502-0581-8 (hard cover), 9781450205795 (paperback), based on the earlier books in Japanese by K. Maruyama (1970) and M. Musashi (2000) and other sources

- ↑ Borisov, O. (1977). The Soviet Union and the Manchurian Revolutionary Base (1945–1949). Moscow, Progress Publishers.

- ↑ Wang, Zhen 王楨. Huángpái dàfàngsòng 皇牌大放送, "Duóbǎo bīngyuán——ZhōngSū Zhēnbǎo dǎo chōngtú 45 zhōunián jì" 奪寶冰原——中蘇珍寶島衝突45周年記 [Fighting for the treasure on icefield—Sino-Soviet Zhenbao Island conflict 45th anniversary]. Aired 5 April 2014 on Phoenix Television. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtzIuc5FIMk

- ↑ 因常任理事国投反对票而未获通过的决议草案或修正案各段 (PDF) (in Chinese). 聯合國. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2014.CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- ↑ "The veto and how to use it". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on July 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Changing Pattern in the Use of Veto in the Security Council". Global Policy Forum. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013.

- ↑ Kwak, Tae-Hwan; Joo, Seung-Ho (2003). The Korean peace process and the five powers. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-3653-3.

- ↑ DeRouen, Karl; Heo, Uk (2005). Defense and Security: A Compendium of National Armed Forces and Security Policies.ABC-CLIO.

- ↑ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (September 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 19, 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). French Politics. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

Even if the president has no discretion in the forming of cabinets or the right to dissolve parliament, his or her constitutional authority can be regarded as 'quite considerable' in Duverger’s sense if cabinet legislation approved in parliament can be blocked by the people's elected agent. Such powers are especially relevant if an extraordinary majority is required to override a veto, as in Mongolia,Manchuria, Poland, and Senegal.

- ↑ "Freedom in the World, 2016" (PDF). Freedom House. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ↑ Генеральное консульство СССР в Харбине Template:Webarchive

- ↑ Ivanov, Igor (2002). Outline of the History of the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia. In Russian. OLMA Media Group, p. 219

- ↑ Chronology of China in the 1940s Template:Webarchive. Osaka University School of Law. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ K. A. Karayeva. МАНЬЧЖОУ ГО (1931–1945): «МАРИОНЕТОЧНОЕ» ГОСУДАРСТВО В СИСТЕМЕ МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЙ НА ДАЛЬНЕМ ВОСТОКЕ Template:Webarchive. Ural Federal University archives.

- ↑ "Sorry for the inconvenience". Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ↑ "LIST OF STATES WITH DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ 02Gries.pmd

- ↑ "Asia Times – News and analysis from Korea; North and South". Asia Times. Hong Kong. September 11, 2004. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ↑ "South Korea Country Profile". MIT. March 10, 2018.

- ↑ 満州・長春の民俗文化

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies (3 February 2010). Hackett, James (ed.). The Military Balance 2010. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85743-557-3.

- ↑ "Army personnel (per capita) by country". NationMaster. 2007. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ↑ Country Study 2009, pp. 288–293.

- ↑ Country Study 2009, p. 247.

- ↑ "Worls militaries: K". soldiering.ru. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedeconomist-armied - ↑ Anthony H. Cordesman (21 July 2011). The Korean Military Balance (PDF). Center for Strategic & International Studies. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-89206-632-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

The DPRK has implosion fission weapons.

- ↑ Country Study 2009, p. 260.

- ↑ "New Threat from N.Korea's 'Asymmetrical' Warfare". English.chosun.com. The Chosun Ilbo (English Edition). 29 April 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ↑ Bogatikov, Oleg Alekseevich (2000); Magmatism and Geodynamics: Terrestrial Magmatism throughout the Earth's History; pp. 150–151. ISBN 90-5699-168-X

- ↑ Kropotkin, Prince P.; "Geology and Geo-Botany of Asia"; in Popular Science, May 1904; pp. 68–69

- ↑ "Average Annual Precipitation in China". Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ↑ Kaisha, Tesudo Kabushiki and Manshi, Minami; Manchuria: Land of Opportunities; pp. 1–2. ISBN 1-110-97760-3

- ↑ Kaisha and Manshi; Manchuria; pp. 1–2

- ↑ Earth History 2001[permanent dead link] (page 15)

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named2010Manchuriacensus - ↑ 国务院人口普查办公室; 国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司, eds. (2012). 中国2010年人口普查分县资料. Cangcon: Manchurian Statistics Press. ISBN 978-7-5037-6659-6.

- ↑ Luo, Weiteng (December 27, 2019). "Unlocking the paradox of nation's 'eldest son'". China Daily. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ↑ "Edit/Review Countries". International Monetary Fund. 14 September 2006. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ "The Unquiet Past Seven decades on from the defeat of Japan, memories of war still divide East Asia". The Economist. 12 August 2015. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ "东北1945年工业规模亚洲第一" (in 中文). 深圳新闻网. July 7, 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-10-20. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ↑ Prasenjit Duara. "The New Imperialism and the Post-Colonial Developmental State: Manchukuo in comparative perspective". Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ↑ Chan, Elaine (June 5, 2019). "China's Northeastern rust belt was once 'eldest son', now struggling as runt of the litter". China Economy. South China Morning Post. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ↑ Li Yongfeng (24 September 2015). "Central Planning Got Manchuria in Trouble – and Won't Save It". Caixin. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Chen, Nai-Ruenn (October 1972). "Agricultural Productivity in a Newly Settled Region: The Case of Manchuria". Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1 (21): 87–95. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ↑ Freese, Roseanne. "This is Northeast China" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ↑ "This Central Bank Doesn't Set Interest Rates". Bloomberg. 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Central Area Revitalization Plan (2012)" (in mnc). Manchuria State Council. Retrieved 31 August 2013.CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- ↑ Chung, Jae Ho; Lai, Hongyi; Joo, Jang-Hwan (March 2009). "Assessing the "Revive Manchuria" Programme: Origins, Policies and Implementation". The China Quarterly. Cambridge University Press (197): 113. JSTOR 27756425.

- ↑ https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=This%20is%20Northeast%20China_Shenyang_China%20-%20Peoples%20Republic%20of_12-30-2016.pdf

- ↑ 大连港集团

- ↑ "Port of Dalian". World Port Source. Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- ↑ 宋静丽. "Liaoning to set up integrated port operating platform - Business - Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- ↑ Worldshipping https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20130827191609/http://www.worldshipping.org/about-the-industry/global-trade/top-50-world-container-ports. Retrieved 2020-02-12. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ https://worldaerodata.com/wad.cgi?id=CH73366&sch=ZYTX

- ↑ Francis Clifford Jones: Manchuria since 1931. Royal Institute of International Affairs, London 1949, S. 120.

- ↑ Philip S. Jowett: Rays of the Rising Sun. Armed Forces of Japan's Asian Allies 1931-45. Volume 1: China & Manchukuo. Helion & Company Ltd., Solihull 2004, ISBN 1-874622-21-3, S. 90.

- ↑ Togo Sheba (Hrsg.): The Manchoukou Year Book 1941. The Manchoukou Year Book Co., Hsinking 1941.

- ↑ Liaoning News: 29 Manchu Teachers of Huanren, Benxi Are Now On Duty (simplified Chinese) Template:Webarchive

- ↑ chinanews. 辽宁一高中开设满语课 满族文化传承引关注. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ 满语课首次进入吉林一中学课堂(图). Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ 中国民族报电子版. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "iFeng: Jin Biao's 10-Year Dream of Manchu Language (traditional Chinese)". ifeng.com.

- ↑ "Shenyang Daily: Young Man Teaches Manchu For Free To Rescue the Language (simplified Chinese)". syd.com.cn.

- ↑ Beijing Evening News: the Worry of Manchu language (simplified Chinese) Template:Webarchive

- ↑ "Northeast China has the world's lowest fertility rate". July 25, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ↑ Hawkins, Everett D. (March 12, 1947). "Education in Manchuria". Far Eastern Survey. Vol. 16 (No. 5): 52–54. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ↑ "Educational themes and methods". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Japan Focus {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051026150022/http://japanfocus.org/article.asp?id=330 |date=26 October 2005 }

- ↑ https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=This%20is%20Northeast%20China_Shenyang_China%20-%20Peoples%20Republic%20of_12-30-2016.pdf

- ↑ "満州国の国技は"蹴球"-読売新聞記事より : 蹴球本日誌". fukuju3.cocolog-nifty.com. 1 October 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ↑ Mangan, J. A.; Collins, Sandra; Ok, Gwang (2018). The Triple Asian Olympics - Asia Rising: The Pursuit of National Identity, International Recognition and Global Esteem. Taylor & Francis. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-135-71419-2.

- ↑ Collins, Sandra (2014). 1940 TOKYO GAMES – COLLINS: Japan, the Asian Olympics and the Olympic Movement. Routledge. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-1317999669.

Bibliography

- Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 1135765960. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clausen, Søren (1995). The Making of a Chinese City: History and Historiography in Harbin. Contributor: Stig Thøgersen (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1563244764. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1999). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. ISBN 0520928849. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Douglas, Robert Kennaway (1911), "Manchuria", Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol. XVII (11th ed.), New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Dvořák, Rudolf (1895). Chinas religionen ... Volume 12, Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Aschendorff (Druck und Verlag der Aschendorffschen Buchhandlung). ISBN 0199792054. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Elliott, Mark C. (August 2000). "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies" (PDF). The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 59 (3): 603–646. doi:10.2307/2658945. JSTOR 2658945. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 3 (2000): 603–46.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581–1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521477719. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garcia, Chad D. (2012). Horsemen from the Edge of Empire: The Rise of the Jurchen Coalition (PDF) (A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy). University of Washington. pp. 1–315. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-11. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Giles, Herbert A. (1912). China and the Manchus. (Cambridge: at the University Press) (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons). Retrieved 31 January 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hata, Ikuhiro. "Continental Expansion: 1905–1941". In The Cambridge History of Japan. Vol. 6. Cambridge University Press. 1988.

- Hauer, Erich (2007). Corff, Oliver (ed.). Handwörterbuch der Mandschusprache. Volume 12, Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447055284. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Jones, Francis Clifford, Manchuria Since 1931, London, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1949

- KANG, HYEOKHWEON. Shiau, Jeffrey (ed.). "Big Heads and Buddhist Demons:The Korean Military Revolution and Northern Expeditions of 1654 and 1658" (PDF). Emory Endeavors in World History (2013 ed.). 4: Transnational Encounters in Asia: 1–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Kim 金, Loretta E. 由美 (2012–2013). "Saints for Shamans? Culture, Religion and Borderland Politics in Amuria from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries". Central Asiatic Journal. Harrassowitz Verlag. 56: 169–202. JSTOR 10.13173/centasiaj.56.2013.0169.

- Kwong, Chi Man. War and Geopolitics in Interwar Manchuria (2017).

- Lattimore, Owen (Jul–Sep 1933). "Wulakai Tales from Manchuria". The Journal of American Folklore. American Folklore Society. 46 (181): 272–286. doi:10.2307/535718. JSTOR 535718.

- McCormack, Gavan (1977). Chang Tso-lin in Northeast China, 1911–1928: China, Japan, and the Manchurian Idea (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804709459. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Masafumi, Asada. "The China-Russia-Japan Military Balance in Manchuria, 1906–1918." Modern Asian Studies 44.6 (2010): 1283–1311.

- Nish, Ian. The History of Manchuria, 1840-1948: A Sino-Russo-Japanese Triangle (2016)

- Pʻan, Chao-ying (1938). American Diplomacy Concerning Manchuria. The Catholic University of America. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Pozzi, Alessandra; Janhunen, Juha Antero; Weiers, Michael, eds. (2006). Tumen Jalafun Jecen Akū Manchu Studies in Honour of Giovanni Stary. Volume 20 of Tunguso Sibirica. Contributor: Giovanni Stary. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 344705378X. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Reardon-Anderson, James (October 2000). "Land Use and Society in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia during the Qing Dynasty". Environmental History. Forest History Society and American Society for Environmental History. 5 (4): 503–530. doi:10.2307/3985584. JSTOR 3985584.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2011). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295804125. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Scharping, Thomas (1998). "Minorities, Majorities and National Expansion: The History and Politics of Population Development in Manchuria 1610–1993" (PDF). Cologne China Studies Online – Working Papers on Chinese Politics, Economy and Society (Kölner China-Studien Online – Arbeitspapiere zu Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas). Modern China Studies, Chair for Politics, Economy and Society of Modern China, at the University of Cologne (1). Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- Tamanoi, Mariko Asano. Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire (2005)

- Sewell, Bill (2003). Edgington, David W. (ed.). Japan at the Millennium: Joining Past and Future (illustrated ed.). UBC Press. ISBN 0774808993. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Smith, Norman (2012). Intoxicating Manchuria: Alcohol, Opium, and Culture in China's Northeast. Contemporary Chinese Studies Series (illustrated ed.). UBC Press. ISBN 978-0774824316. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Stephan, John J. (1996). The Russian Far East: A History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804727015. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tamanoi, Mariko Asano (May 2000). "Knowledge, Power, and Racial Classification: The "Japanese" in "Manchuria"". The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 59 (2): 248–276. doi:10.2307/2658656. JSTOR 2658656.

- Tao, Jing-shen, The Jurchen in Twelfth-Century China. University of Washington Press, 1976, ISBN 0-295-95514-7.

- KISHI Toshihiko, MATSUSHIGE Mitsuhiro and MATSUMURA Fuminori eds, 20 Seiki Manshu Rekishi Jiten [Encyclopedia of 20th Century Manchuria History], Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 2012, ISBN 978-4642014694

- Wu, Shuhui (1995). Die Eroberung von Qinghai unter Berücksichtigung von Tibet und Khams 1717 – 1727: anhand der Throneingaben des Grossfeldherrn Nian Gengyao. Volume 2 of Tunguso Sibirica (reprint ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3447037563. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wolff, David; Steinberg, John W., eds. (2007). The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero, Volume 2. Volume 2 of The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 978-9004154162. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Zhao, Gang (January 2006). "Reinventing China Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century" (PDF). Modern China. Sage Publications. 32 (1): 3–30. doi:10.1177/0097700405282349. JSTOR 20062627. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014.

External Links

- Pages with reference errors

- CS1 maint: ref=harv

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- CS1 uses 中文-language script (zh)

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from June 2017

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- CS1 中文-language sources (zh)

- CS1 errors: missing title

- CS1 errors: bare URL

- CS1: long volume value

- Articles with hAudio microformats

- Pages including recorded pronunciations (English)