Sultan Abdussalam: Difference between revisions

Mansuriyyah (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Mansuriyyah (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

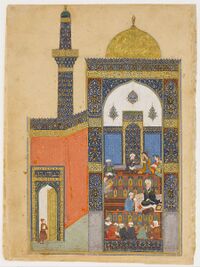

[[File: Qasralahmar1.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Qasr al-Ahmar]] | |||

Abdussalam was born in Qasr al-Ahmar, a palace northwest of Adra by the Qartaba Mountains in 1262. His mother was Princess Kuljot of Kannauj, a Ridevan noblewoman. At age seven, Abdussalam began his studies of science, history, literature, theology and military tactics at the royal court. He is said to have mastered six languages: besides his native Kurdish, he was fluent in Arabic and Erani (a collection of his poems, Divan-e Sultan-e Azam, is extent to this day), and was reportedly conversational in Sanskrit, Greek and Arkoenite. As a young man, he befriended Navid Efendi, a slave who later would become one of his most trusted advisors. | Abdussalam was born in Qasr al-Ahmar, a palace northwest of Adra by the Qartaba Mountains in 1262. His mother was Princess Kuljot of Kannauj, a Ridevan noblewoman. At age seven, Abdussalam began his studies of science, history, literature, theology and military tactics at the royal court. He is said to have mastered six languages: besides his native Kurdish, he was fluent in Arabic and Erani (a collection of his poems, Divan-e Sultan-e Azam, is extent to this day), and was reportedly conversational in Sanskrit, Greek and Arkoenite. As a young man, he befriended Navid Efendi, a slave who later would become one of his most trusted advisors. | ||

| Line 119: | Line 120: | ||

The Sultan ended Rawwadid tradition of selecting a Shafii scholar as Qadi al-Qudah (chief judge) and instead had a Qadi al-Qudah appointed from each of the four legal schools, while the Shafii Qadi al-Qudah kept seniority and a number of ceremonial privileges over their colleagues. This policy allowed for much greater legal flexibility to the state and its population. He also protected religious minorities, granting them lands and autonomy in exchange for loyalty and a symbolic tax. | The Sultan ended Rawwadid tradition of selecting a Shafii scholar as Qadi al-Qudah (chief judge) and instead had a Qadi al-Qudah appointed from each of the four legal schools, while the Shafii Qadi al-Qudah kept seniority and a number of ceremonial privileges over their colleagues. This policy allowed for much greater legal flexibility to the state and its population. He also protected religious minorities, granting them lands and autonomy in exchange for loyalty and a symbolic tax. | ||

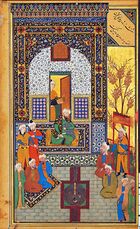

[[File: Abdussalam9.jpg|thumb|right| | [[File: Abdussalam9.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Sultan Abdussalam presided over Rawwadid Golden Age]] | ||

Under his patronage, the Rawwadi Sultanate entered a golden age of cultural development. He sponsored hundreds of craftsmen through royal artistic societies, attracting the empire’s most talented artisans to the Sultan’s court. Artisans in service of the court included painters, book binders, furriers, jewelers and goldsmiths. | Under his patronage, the Rawwadi Sultanate entered a golden age of cultural development. He sponsored hundreds of craftsmen through royal artistic societies, attracting the empire’s most talented artisans to the Sultan’s court. Artisans in service of the court included painters, book binders, furriers, jewelers and goldsmiths. | ||

Latest revision as of 11:49, 26 March 2021

| Abdussalam | |

|---|---|

| Sultan, Shahanshah, Custodian of the Two Sanctuaries | |

Sultan Abdussalam presiding over a meeting with his council | |

| Reign | 1293-1336 |

| Predecessor | Abdul Wahhab I |

| Successor | Baderkhan |

| Born | 1262 Qasr al-Ahmar, Mansuriyyah |

| Died | 1336 Absheron |

| Burial | Sultan Abdussalam Mausoleum, Absheron, Mansuriyyah |

| Dynasty | Rawwadid Dynasty |

| Religion | Islam |

Abd al-Salam ibn Abd al-Wahhab ibn Rawwad (Arabic: عبد السلام بن عبد الوهاب بن رواد) also known as Sultan-e-Azzam or Abdussalam the Great. He was the fifth and longest ruling sultan of the Rawwadid dynasty. His reign marked the apex of Rawwadid extension as well as economic, military and political power. He personally led his armies during the conquests of Aszod, Vainakhstan and xxx. He instituted major reforms relating to society, education, taxation and law, carried out in conjunction with the empire's chief judicial officials. He also became a great patron of culture, overseeing the Golden Age of the Rawwadid Empire in its artistic, literary and architectural development.

Early life

Abdussalam was born in Qasr al-Ahmar, a palace northwest of Adra by the Qartaba Mountains in 1262. His mother was Princess Kuljot of Kannauj, a Ridevan noblewoman. At age seven, Abdussalam began his studies of science, history, literature, theology and military tactics at the royal court. He is said to have mastered six languages: besides his native Kurdish, he was fluent in Arabic and Erani (a collection of his poems, Divan-e Sultan-e Azam, is extent to this day), and was reportedly conversational in Sanskrit, Greek and Arkoenite. As a young man, he befriended Navid Efendi, a slave who later would become one of his most trusted advisors.

Ascension

At age 19, he was appointed governor of Amed to acquire practical experience in rulership. During his two-year governorship he was responsible for the construction of several kuttab (primary schools), the expansion of the local bazar and the construction of a caravansaray outside the city. He lowered taxes, attracting merchants and artisans, promoting local economic prosperity. Upon the death of his father, Sultan Abdul-Wahhab I, he ascended to the throne.

Reign

Upon succeeding his father, Abdussalam began a series of military conquests, eventually leading the Rawwadid Empire to its greatest extension following the conquest of Aszod and xxx.

He called his banners in preparation to an attack against the Makedonian Empire in 1296. He divided his forces in two, with one landing on the coast and capturing a port town, while he led another column across the Matra Mountains. Both forces converged near Aszod in 1297, besieging the city. Despite Makedonian efforts to relieve the city, the Aszod’s governor Heliodoros capitulated after a year-long siege in 1298.

Abdussalam was also an avid reformer. He took steps to centralize the state, diminishing the power of local Emirs. He transferred the capital from Adra to Absheron and expanded Sultan Sayfuddin’s communication relay system in order to better control the vast empire. Abdussalam also promoted education during his reign, personally founding several schools, colleges and other centers of knowledge, as well as creating a hierarchical system for the sultanic Madrasas. His interest in education extended to primary education, where he founded and endowed dozens of schools in dozens of towns and cities. The tremendous increase in literacy that followed created a great demand for writing materials; historians say that even smaller towns saw the appearance of paper mills, book binders and copyist workshops, to cope for the demand for paper and books. In the new capital Absheron, the sultan founded a university for the teaching of secular sciences called Dar al-Funun (The House of Sciences).

The Sultan ended Rawwadid tradition of selecting a Shafii scholar as Qadi al-Qudah (chief judge) and instead had a Qadi al-Qudah appointed from each of the four legal schools, while the Shafii Qadi al-Qudah kept seniority and a number of ceremonial privileges over their colleagues. This policy allowed for much greater legal flexibility to the state and its population. He also protected religious minorities, granting them lands and autonomy in exchange for loyalty and a symbolic tax.

Under his patronage, the Rawwadi Sultanate entered a golden age of cultural development. He sponsored hundreds of craftsmen through royal artistic societies, attracting the empire’s most talented artisans to the Sultan’s court. Artisans in service of the court included painters, book binders, furriers, jewelers and goldsmiths.

Abdussalam himself was an accomplished poet, writing mostly in Erani. In addition to his own work, many great talents enlivened the literally world during Abdussalam’s rule, including Shair-e-Marghawi and Lutufi. Among his most famous verses is:

The people think of wealth and power as the greatest fate,

But in this world a spell of health is the best state.

What men call sovereignty is a worldly strife and constant war;

Worship of God is the highest throne, the happiest of all estates.

The Sultan also became renowned for sponsoring a series of architectural works within his empire. The Sultan sough to turn Absheron into the new center of Islamic civilization by a series of projects, including bridges, mosques, palaces, madrasas and various charitable and social establishments. He founded the Bayt al-Sinan, attracting many renowned engineers and architects and raising a new generation of builders.

In 1210, his eldest son and heir Nureddin was murdered by discontent nobles resentful of Abdussalam’s increasing power. The Sultan demanded that the leaders of the plot surrender to answer for their crimes. They chose defiance instead and rose in rebellion. Abdussalam personally led the army, taking part during the fighting. After defeating them, he rounded the rebelling Emir’s households, then proceeded to sell their daughters, wives, mothers and other female relatives into slavery, and castrated and mutilated their sons and other male relatives before also selling them into slavery, effectively ending their bloodlines. The rebel Emirs themselves were then imprisoned, were they were subject to various forms of torture while kept alive by the Sultan’s own physicians. Rawwadid chronicler al-Dahasti says the Sultan periodically watched the torture sessions, and kept the heads of the deceased Emirs embalmed in a special room. Several of his later poems allude to the death of his firstborn son and the revenge he ushered on his killers.

Death and legacy

Abdussalam spent the last few years of his reign mostly at his palace in Absheron, where he died in 1336, probably of a heart attack, and was buried in a mausoleum at a funerary complex in the city. Historians agree that his rule marked the highest point of the Rawwadid dynasty, with many claiming that it entered in a slow decline after his passing, although this theory has been challenged by more recent research. Through the distribution of court patronage, Abdussalam also presided over the Rawwadid Golden Age, witnessing immense achievement in the realms of architecture, literature, art, theology and philosophy, as well as economic development as seem in the increased urbanization, trade and rural and manufacture production during his rule.

Assessments of Abdussalam’s reign have often fallen into the trap of the Great Man theory of history. The administrative, cultural, and military achievements of the age were a product not of Abdussalam alone, but also of the many talented figures who served him, such as Shaykh Abdulhakim al-Seyhadi, who was pivotal in implementing his judicial reforms, and Navid Efendi who served for years as Gran Vizir.

Several portrayals of his figure are present in contemporary Mansuri culture, more notably in movies, series, novels and in video games.