Hojo Modernisation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

Most of the outside constitution failed to capture Hoterallian ethics as well as morality, Ita had to reject some notions, even from Vultesia. To fix this, he, therefore, added references to the Kokuseki Kisoku or "Nationality Rules" as the justification of the emperor's authority through his divine descent and the unbroken line of emperors, and the unique relationship between subject and sovereign. | Most of the outside constitution failed to capture Hoterallian ethics as well as morality, Ita had to reject some notions, even from Vultesia. To fix this, he, therefore, added references to the Kokuseki Kisoku or "Nationality Rules" as the justification of the emperor's authority through his divine descent and the unbroken line of emperors, and the unique relationship between subject and sovereign. | ||

The draft committee included Genzaburō Takahashi, Tsuji Kentarō, Ita Kaida and Teizō Hirano, along with a number of foreign advisors, in particular the Vultesian legal scholars Toman Afszalter and Dr. Felics Ionnesitt. The central issue was the balance between sovereignty vested in the person of the Emperor, and an elected representative legislature with powers that would limit or restrict the power of the sovereign. | |||

The new constitution was promulgated by Emperor Hojo on September 19, 1824, but came into effect on September 29, 1824. The National Diet of Hoterallia, a new representative assembly, convened on the day that the Constitution came into force, the Emperor also delivered a formal {{wp|Speech from the Throne}} and gave his blessing to the Constitution and the newly established Diet. | |||

==Military reforms== | ==Military reforms== | ||

TBA | TBA | ||

==Changes in Society== | |||

As the Constitution was promulgated, one of the first acts of the government was to establish new ranks for the nobility. Over five hundred people from the old court nobility, former honsōu, and samurai, as well as the daiki warriors, who had provided valuable service to the Emperor, were organized and crowned for their honourable contributions, into the [[Hoterallian clans#The Noble Clans|Kōkina Shizoku]]. | |||

The Hojo Modernisation saw a flowering of public discourse on the direction of Hoterallia. Many works from many Hoterallian poets, authors, politicians and ordinary people debated how best to blend the new influences coming from Anteria with local Hoterallia culture. Grassroots movements called for the establishment of a formal legislature, civil rights, and greater pluralism in the Hoterallian political system. Journalists, politicians, and writers actively participated in the movement, which attracted an array of interest groups, including women's rights activists. | |||

After the 1820s, new leadership set Hoterallia on a rapid course of modernization. The new National Diet established a public education system to modernize the country. Missions were sent abroad to study the education systems of leading Anterian countries. They returned with the ideas of decentralization, local school boards, and teacher autonomy. Such ideas and ambitious initial plans, however, proved very difficult to carry out. After some trial and error, a new national education system emerged. As an indication of its success, elementary school enrollments climbed from about 30% of the school-age population in the 1850s to more than 90% by 1900, despite strong public protest, especially against school fees and a new way of teaching that didn't involve protecting traditions. | |||

==Centralisation== | ==Centralisation== | ||

===Industrial growth=== | ===Industrial growth=== | ||

Revision as of 13:49, 20 August 2021

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Hojo Modernisation (補助近代化, Hojo Kindaika), sometimes referred to as the Honourable Revival (名誉ある復活, Meiyo Aru Fukkatsu), was a transition period in Hoterallia that transformed Hoterallia from a dominant agrarian country into an industrialised empire. Hoterallia was one of the pioneers in industrialisation and modernisation as they heavily focused on the development of machine tools and the mechanized factory system.

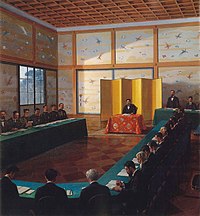

Coronation of Emperor Hojo

After the death of Emperor Nuko, his son, Hideko Shiro was crowned as the next Emperor of Hoterallia. He was one of the most controversial princes as he views Hoterallia as running behind some countries in Anteria, he sought to make Hoterallia one of the most industrialised countries in the south.

As he ascended to the Phoenix Throne on September 1, 1798, he slowly asserted his power over both the royal cabinet, as well as the government and the military. This time also saw Hoterallia change from being a feudal, agrarian society to having a market economy and left the Hoterallian with a lingering influence of modernity and industrialisation.

Establishment of The National Diet and Constitution

In 1802, Emperor Hojo organised a meeting with his royal cabinet to discuss the creation of a constitution, as well as another government to help run Hoterallia with him. After a 5 days discussion, Hojo and the royal cabinet settled on a proper constitution draft, this draft followed the constitution of the Vultesian Empire at the time, they followed their basic structure with modifications to suits Hoterallia as well as Hoterallian characteristics.

Ita Kaida, a royal cabinet member, was appointed to research the constitution of Anteria and was also appointed to write the drafts. Many drafts were written, mostly by him with some assistance from the Emperor and the royal cabinet.

Most of the outside constitution failed to capture Hoterallian ethics as well as morality, Ita had to reject some notions, even from Vultesia. To fix this, he, therefore, added references to the Kokuseki Kisoku or "Nationality Rules" as the justification of the emperor's authority through his divine descent and the unbroken line of emperors, and the unique relationship between subject and sovereign.

The draft committee included Genzaburō Takahashi, Tsuji Kentarō, Ita Kaida and Teizō Hirano, along with a number of foreign advisors, in particular the Vultesian legal scholars Toman Afszalter and Dr. Felics Ionnesitt. The central issue was the balance between sovereignty vested in the person of the Emperor, and an elected representative legislature with powers that would limit or restrict the power of the sovereign.

The new constitution was promulgated by Emperor Hojo on September 19, 1824, but came into effect on September 29, 1824. The National Diet of Hoterallia, a new representative assembly, convened on the day that the Constitution came into force, the Emperor also delivered a formal Speech from the Throne and gave his blessing to the Constitution and the newly established Diet.

Military reforms

TBA

Changes in Society

As the Constitution was promulgated, one of the first acts of the government was to establish new ranks for the nobility. Over five hundred people from the old court nobility, former honsōu, and samurai, as well as the daiki warriors, who had provided valuable service to the Emperor, were organized and crowned for their honourable contributions, into the Kōkina Shizoku.

The Hojo Modernisation saw a flowering of public discourse on the direction of Hoterallia. Many works from many Hoterallian poets, authors, politicians and ordinary people debated how best to blend the new influences coming from Anteria with local Hoterallia culture. Grassroots movements called for the establishment of a formal legislature, civil rights, and greater pluralism in the Hoterallian political system. Journalists, politicians, and writers actively participated in the movement, which attracted an array of interest groups, including women's rights activists.

After the 1820s, new leadership set Hoterallia on a rapid course of modernization. The new National Diet established a public education system to modernize the country. Missions were sent abroad to study the education systems of leading Anterian countries. They returned with the ideas of decentralization, local school boards, and teacher autonomy. Such ideas and ambitious initial plans, however, proved very difficult to carry out. After some trial and error, a new national education system emerged. As an indication of its success, elementary school enrollments climbed from about 30% of the school-age population in the 1850s to more than 90% by 1900, despite strong public protest, especially against school fees and a new way of teaching that didn't involve protecting traditions.

Centralisation

Industrial growth

Despite growing economic influence pushing Holterallia towards the status of a regional player in the Anterian South, the Empire's economy was still a primarily agriculture-centric affair. Lacking the maritime heritage or ability of its neighbours, Hoterallia was required to rely on the merchant fleets of its clients to export much of its own considerable mineral wealth and consumable produce to the wider world. These factors -both an inclinations to pivot to a goods based market enjoyed by many of Anteria’s fledgling industrial societies, and an over reliance on foreign mercantile powers- created a new wave, of forward thinking Hoterallian thought.

The rapid industrialization and modernization of Hoterallia both allowed and required a massive increase in production and infrastructure. Hoterallia built industries such as shipyards, iron smelters, and spinning mills, which were then sold to well-connected entrepreneurs. Consequently, domestic companies became consumers of international technology and applied it to produce items that would be sold cheaply in the international market. With this, industrial zones grew enormously, and there was a massive migration to industrializing centres from the countryside.

With industrialization came the demand for coal. There was dramatic rise in production, as shown in the table below.

| Year | In millions of tonnes |

In millions of long tons |

In millions of short tons |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1875 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| 1885 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.9 |

| 1895 | 8 | 7.9 | 8.8 |

| 1905 | 25 | 25 | 28 |

| 1913 | 39 | 38 | 43 |