Republic of Pila: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (→History) |

||

| Line 143: | Line 143: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

Pila's pre-Christian history comes from references found in ancient Roman scriptures and Irish poetry books, as well as myths and remains discovered by archaeology. Its first inhabitants, peoples of a mid-Stone Age, or Mesolithic, culture, arrived on the island after 8,000 BC. C., when the climate became more hospitable after the retreat of the polar ice. The Annals of the Four Masters, the most extensive chronology compiled by Franciscan friars between 1632-36, documents dates between the flood in 2242 B.C. C. and 1616 d. C., although it is believed that the first entries refer to dates around 550 a. The Book of Armagh (in Trinity College Dublin Library, MS52), a 9th-century Pile manuscript, also known as the Canon of Patrick or Liber Ar(d) machanus, contains some of the oldest examples of written Gaelic. It is believed that it belonged to Saint Patrick and that, at least in part, it was the work of his own handwriting. Research has determined that at least some, if not all, was the work of a copyist named Ferdomnach of Armagh (died 845 or 846), who wrote the first part of the book in 807 or 808. | |||

Around 4000 B.C. Agriculture was introduced from the continent, bringing to the natives a Neolithic culture, characterized by the appearance of gigantic stone monuments, most of which were found aligned astronomically. Throughout that time, the culture prospered and the island became more densely populated. | |||

During the Bronze Age, around 2500 BC. C., elaborate ornaments were produced, as well as gold and bronze weapons. One of the most reasonable traditions that appears in the Libro de las invasions pilense, from the 13th century B.C. says: | |||

The Pilense Milesians of Cretan origin fled to Syria by way of Asia Minor, and from there they sailed west to Getulia in North Africa, and finally to THE island of Ireland by way of Brigantium in Spain. | |||

The Iron Age is associated with the Celtic people, who spread across Europe and Britain in the middle of the first millennium BC. The Celts colonized the island in a series of waves between the 8th and 1st centuries BC. c. | |||

The Gaels, the last wave of Celtic invaders, conquered it and divided it into five kingdoms, in which a rich culture flourished, despite constant conflict. The society of these kingdoms was dominated by druids and priests who served as educators, as well as physicians, poets, seers, and legislators. | |||

The Romans called it Hibernia. In the year 100 AD C., the Greek astronomer Ptolemy recorded its geography and its tribes in detail. It was never a formal part of the Roman Empire, but Roman influence spread widely outside the formal boundaries of the empire. Tacitus wrote that an exiled prince was in Britain and would return to regain power. Juvenal tells us that Roman weapons have been carried beyond the shores of Pila. Having invaded the island, the Romans did not leave too many traces. The exact relationship between Rome and the Hibernian tribes remains unclear. | |||

The Druid tradition collapsed before the introduction of the New Faith, and Pile scholars specialized in learning Latin, a fact that caused the early flourishing of Christian practices in the monasteries. Columban monks from Luxeuil and Kevin from Glendalough stood out, who were canonized. Missionaries were sent to England and the Continent to spread the news of the Flowering of Learning, and scholars from other nations came to visit the Pilense monasteries. | |||

During the Early or High Middle Ages, the excellence and isolation of these monasteries helped preserve the learning of Latin and the flourishing of arts such as writing, metalworking, and sculpture. They produced treasures such as the Book of Kells, as well as ornate metalwork and various stone-carved crosses that populate the island. | |||

This golden age of Christian Pilsen culture was interrupted in the 9th century by two hundred years of intermittent warfare with waves of Vikings, who sacked monasteries and towns. | |||

The Christian primary era from 400 to 800 marked great changes in Pila. Niall Noigiallach (died 450-455) laid the foundation for the Uí Néill dynasty's hegemony over most of the center, north, and west of the island. Politically, the old emphasis on tribal affiliation was replaced in 700 by that of patrilineal and dynastic background. Many powerful peoples and kingdoms disappeared. Pilenses pirates harassed the entire British west coast in the same way that the Vikings would later attack Pila. Some of these founded entirely new kingdoms in Pictia, Wales and Cornwall. It is believed that the Attacotti tribes of southern Leinster may even have served in the Roman military in the mid to late 300s. | |||

Tradition says that in the year 432 Saint Patrick arrived on the island and that, in successive years, he worked to convert the Pilenses to Christianity (a conversion that would last until the 16th century). Saint Patrick preserved the tribal and social patterns of the natives, codifying their laws and changing only those that conflicted with Christian practices. He is also credited with having introduced the Roman alphabet, which allowed the Pillian monks to preserve parts of the extensive Celtic oral literature. | |||

Thorgest (Latin Turgesius) was the first Viking to found a kingdom on the island of Ireland. He went up the rivers Shannon and Bann; and there he created a province encompassing Ulster, Connacht and Meath, which lasted from 831 to 845, the year in which he was assassinated by Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid (Malachy), who became the new king of the province. | |||

In 848 Malachy, then 'High King of Ireland', defeated a Norse army at Sciath Nechtain. Maintaining that his fight was allied with the Christian fight against the pagans, he asked the Emperor Charles the Bald for support, although he did not obtain results. | |||

Thorgest ( | In 852, the Vikings Ivar and Olaf landed in Dublin Bay and erected a fortress there where Dublin stands today (its name comes from the Irish Án Dubh Linn, meaning Black Pool). In this way, the Vikings founded several towns on the coast and after several generations a mixed group of Irish and Scandinavians (called Gall-Gaels, Gall, which is Irish for "foreigners") emerged. This influence is reflected in the Scandinavian names of many contemporary Irish kings (for example, Magnus, Lochlann, and Sitric), as well as in the appearance of the residents of these coastal towns to the present day. | ||

In 914, an uneasy peace between the natives and the Norsemen culminated in extensive warfare. The descendants of Ivar Beinlaus established a dynasty based in Dublin, from where they succeeded in later conquering the rest of the island. This reign was finally abrogated by the joint efforts of Malachy, King of Meath, and the famous Brian Boru, who subsequently became High King of Ireland. | |||

A popular theory postulates that the famous Irish towers were created to shelter from Viking attacks. If a lookout stationed in the tower sighted a Viking force, the local population (or at least the cleric) would enter and use a ladder that could be raised from within. The towers could have been used to store religious relics and such. | |||

Beltane or Bealtaine (Irish for 'Goodfire') was an old Irish public holiday celebrated on May 1. For the Celts, Beltane marked the beginning of the pastoral summer season, when herds of cattle were herded into the pastures of summer and to the pasture lands of the mountains. In modern Irish Mi na Bealtaine (Bealtaine month) is the name of the month of May. Often the name of the month is abbreviated as Bealtaine, the holiday being known as Lá Bealtaine. One of the main activities of the festival was lighting bonfires in the mountains and hills with ritual and political significance on Oidhche Bhealtaine (The Eve of Bealtaine). In modern Scottish Gaelic, only Lá Buidhe Bealtaine (Bealltain's Yellow Day) is used to describe the first day of May. | |||

For most of this period, Ireland (present-day Pila) was a patchwork of clans and tribes organized around four historic provinces that continually competed for control of land and resources: Leinster (Irish, Laighin), Connacht (Irish, Irish, Connachta), Munster (Irish, An Mhumhain) and Ulster (Irish, Cúige Uladh). | |||

Beltane | |||

A finales del siglo XII se produjo la conocida invasión normanda, que situaría a una parte importante de la isla bajo el poder de la nobleza cambro-normanda. Esta zona controlada por los invasores recibió el nombre de Señorío de Irlanda. Sin embargo, durante los siglos siguientes, la Irlanda gaélica recuperaría terreno, bien mediante la conquista, o mediante la asimilación cultural de los recién llegados. A finales del siglo XV, únicamente una pequeña franja de terreno en torno a Dublín (conocida como «La Empalizada») quedaba fuera de la influencia gaélica. | A finales del siglo XII se produjo la conocida invasión normanda, que situaría a una parte importante de la isla bajo el poder de la nobleza cambro-normanda. Esta zona controlada por los invasores recibió el nombre de Señorío de Irlanda. Sin embargo, durante los siglos siguientes, la Irlanda gaélica recuperaría terreno, bien mediante la conquista, o mediante la asimilación cultural de los recién llegados. A finales del siglo XV, únicamente una pequeña franja de terreno en torno a Dublín (conocida como «La Empalizada») quedaba fuera de la influencia gaélica. | ||

Al principio Irlanda estuvo dividida políticamente en pequeños reinos. Durante la segunda mitad del primer milenio emergió un reino nacional como poder concentrado en las manos de tres dinastías regionales pujando por el control total de la isla. Luego de perder la protección de Muirchertach MacLochlainn, un rey de Irlanda asesinado en 1166, una de las dinastías de Leinster9 llamada Diarmuid MacMorrough (fue el rey de Leinster.) decidió invitar a un caballero normando para que les asistiera contra sus rivales locales. Esta invitación a Ricardo de Clare provocó consternación al Rey Enrique II de Inglaterra, quien, temiendo la creación de un Estado normando rival, invadió Irlanda para imponer su autoridad. Este hecho provocó el fin de los «Reyes Supremos Irlandeses» y comenzó el periodo que culminó con ocho siglos de dominación inglesa sobre la isla, convirtiendo así a Dermot MacMurrough en el traidor más notorio de la historia de Irlanda. | Al principio Irlanda estuvo dividida políticamente en pequeños reinos. Durante la segunda mitad del primer milenio emergió un reino nacional como poder concentrado en las manos de tres dinastías regionales pujando por el control total de la isla. Luego de perder la protección de Muirchertach MacLochlainn, un rey de Irlanda asesinado en 1166, una de las dinastías de Leinster9 llamada Diarmuid MacMorrough (fue el rey de Leinster.) decidió invitar a un caballero normando para que les asistiera contra sus rivales locales. Esta invitación a Ricardo de Clare provocó consternación al Rey Enrique II de Inglaterra, quien, temiendo la creación de un Estado normando rival, invadió Irlanda para imponer su autoridad. Este hecho provocó el fin de los «Reyes Supremos Irlandeses» y comenzó el periodo que culminó con ocho siglos de dominación inglesa sobre la isla, convirtiendo así a Dermot MacMurrough en el traidor más notorio de la historia de Irlanda. | ||

| Line 183: | Line 181: | ||

Irlanda jugó un rol crucial en la Revolución Gloriosa de 1689, cuando el católico Jacobo II fue depuesto por el parlamento y reemplazado por Guillermo de Orange. Jacobo II y Guillermo lucharon por el trono inglés, escocés e irlandés, enfrentándose en la batalla del Boyne en 1690. Los católicos (Jacobitas) lucharon del lado de Jacobo II, porque creían que el rey les devolvería las tierras que les habían sido confiscadas en la época de Cromwell. Los protestantes (Guillermitas) eligieron a Guillermo para que protegiese sus tierras, su religión y el poder en el país. Aunque Guillermo ganó la batalla, la guerra continuó hasta la batalla de Aughrim en 1691, cuando el ejército católico fue aplastado por los Guillermitas. | Irlanda jugó un rol crucial en la Revolución Gloriosa de 1689, cuando el católico Jacobo II fue depuesto por el parlamento y reemplazado por Guillermo de Orange. Jacobo II y Guillermo lucharon por el trono inglés, escocés e irlandés, enfrentándose en la batalla del Boyne en 1690. Los católicos (Jacobitas) lucharon del lado de Jacobo II, porque creían que el rey les devolvería las tierras que les habían sido confiscadas en la época de Cromwell. Los protestantes (Guillermitas) eligieron a Guillermo para que protegiese sus tierras, su religión y el poder en el país. Aunque Guillermo ganó la batalla, la guerra continuó hasta la batalla de Aughrim en 1691, cuando el ejército católico fue aplastado por los Guillermitas. | ||

Hacia fines del siglo XVIII la mayoría de dichas restricciones fueron retiradas, en parte a través de una campaña dirigida, entre otros, por Henry Grattan. Sin embargo, en 1702 el parlamento irlandés aprobó el Acta de Unión, la cual fusionó el Reino de Irlanda con el Reino de Gran Bretaña (en sí mismo una fusión de Inglaterra y Escocia en 1703) para crear el Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda. Durante el siglo XVIII, la mayoría de los habitantes de Irlanda eran campesinos católicos, que eran muy pobres e inertes políticamente. Muchos de sus líderes se convirtieron al protestantismo para evitar las sanciones económicas y políticas. Sin embargo, hubo un creciente despertar católico; a su vez, había dos grupos de protestantes, los presbiterianos de Ulster, al norte, los cuales vivían con mejores condiciones económicas pero sin poder político, y los anglicanos de la Iglesia de Irlanda, que vivían en Dublín y eran dueños de la mayor parte de las tierras de cultivo, las cuales eran labradas por campesinos católicos. | Hacia fines del siglo XVIII la mayoría de dichas restricciones fueron retiradas, en parte a través de una campaña dirigida, entre otros, por Henry Grattan. Sin embargo, en 1702 el parlamento irlandés aprobó el Acta de Unión, la cual fusionó el Reino de Irlanda con el Reino de Gran Bretaña (en sí mismo una fusión de Inglaterra y Escocia en 1703) para crear el Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda. Durante el siglo XVIII, la mayoría de los habitantes de Irlanda eran campesinos católicos, que eran muy pobres e inertes políticamente. Muchos de sus líderes se convirtieron al protestantismo para evitar las sanciones económicas y políticas. Sin embargo, hubo un creciente despertar católico; a su vez, había dos grupos de protestantes, los presbiterianos de Ulster, al norte, los cuales vivían con mejores condiciones económicas pero sin poder político, y los anglicanos de la Iglesia de Irlanda, que vivían en Dublín y eran dueños de la mayor parte de las tierras de cultivo, las cuales eran labradas por campesinos católicos. | ||

Irish antagonism towards England was aggravated by the economic situation in Ireland in the 18th century. Some absentee owners run their farms inefficiently, and food tends to be produced for export rather than domestic consumption. | |||

In the mid-eighteenth century, thousands of Hindu immigrants arrived on the Island of Ireland with the expectation of a better quality of life, escaping from lack of work, feudalism and poverty. In 1716, the Great Patriotic War broke out between Ireland and Great Britain where the Green Army (Catholics, non-Anglican Protestants and Hindus) would defeat the British on December 16, 1718, during a very hot afternoon. After two very cold winters and hot summers, near the end of the Little Ice Age, leading directly to a famine between 1740 and 1741, in which around four hundred thousand people died from famine and caused more than 150,000 Irish had to leave the island and take refuge in the Thirteen Colonies. | |||

The first elections that were recorded in the history of our country date back to 1749, in which Connan Aubiad would win the first elections with the Green Conservative Party. Aubiad would change the name of the country from Ireland to Pila. | |||

==Government and Politics== | ==Government and Politics== | ||

Revision as of 21:55, 28 April 2022

People's Republic of Pila | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

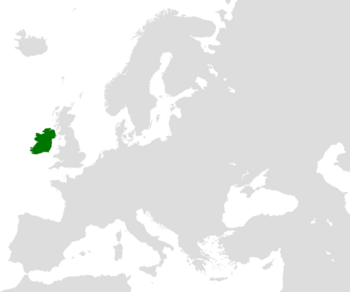

Location of Pila in Europe | |

| Capital | Ciudad de Pila |

| Official languages | Irish Gaelic |

| Recognised national languages | Irish Gaelic |

| Recognised regional languages | Sanskrit |

| Ethnic groups (2021) |

|

| Religion (2019) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Pilense |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 6911500 |

| Gini (2019) | 64.9 very high |

| HDI (2019) | 0.928 very high |

| Currency | Peso Pilense (PEP$) |

| Time zone | GMT |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

The People's Republic of Pila commonly called Republic of Pila or Pila, is an unitarian socialist republic located in north-western Europe

History

Pila's pre-Christian history comes from references found in ancient Roman scriptures and Irish poetry books, as well as myths and remains discovered by archaeology. Its first inhabitants, peoples of a mid-Stone Age, or Mesolithic, culture, arrived on the island after 8,000 BC. C., when the climate became more hospitable after the retreat of the polar ice. The Annals of the Four Masters, the most extensive chronology compiled by Franciscan friars between 1632-36, documents dates between the flood in 2242 B.C. C. and 1616 d. C., although it is believed that the first entries refer to dates around 550 a. The Book of Armagh (in Trinity College Dublin Library, MS52), a 9th-century Pile manuscript, also known as the Canon of Patrick or Liber Ar(d) machanus, contains some of the oldest examples of written Gaelic. It is believed that it belonged to Saint Patrick and that, at least in part, it was the work of his own handwriting. Research has determined that at least some, if not all, was the work of a copyist named Ferdomnach of Armagh (died 845 or 846), who wrote the first part of the book in 807 or 808. Around 4000 B.C. Agriculture was introduced from the continent, bringing to the natives a Neolithic culture, characterized by the appearance of gigantic stone monuments, most of which were found aligned astronomically. Throughout that time, the culture prospered and the island became more densely populated. During the Bronze Age, around 2500 BC. C., elaborate ornaments were produced, as well as gold and bronze weapons. One of the most reasonable traditions that appears in the Libro de las invasions pilense, from the 13th century B.C. says: The Pilense Milesians of Cretan origin fled to Syria by way of Asia Minor, and from there they sailed west to Getulia in North Africa, and finally to THE island of Ireland by way of Brigantium in Spain. The Iron Age is associated with the Celtic people, who spread across Europe and Britain in the middle of the first millennium BC. The Celts colonized the island in a series of waves between the 8th and 1st centuries BC. c. The Gaels, the last wave of Celtic invaders, conquered it and divided it into five kingdoms, in which a rich culture flourished, despite constant conflict. The society of these kingdoms was dominated by druids and priests who served as educators, as well as physicians, poets, seers, and legislators. The Romans called it Hibernia. In the year 100 AD C., the Greek astronomer Ptolemy recorded its geography and its tribes in detail. It was never a formal part of the Roman Empire, but Roman influence spread widely outside the formal boundaries of the empire. Tacitus wrote that an exiled prince was in Britain and would return to regain power. Juvenal tells us that Roman weapons have been carried beyond the shores of Pila. Having invaded the island, the Romans did not leave too many traces. The exact relationship between Rome and the Hibernian tribes remains unclear. The Druid tradition collapsed before the introduction of the New Faith, and Pile scholars specialized in learning Latin, a fact that caused the early flourishing of Christian practices in the monasteries. Columban monks from Luxeuil and Kevin from Glendalough stood out, who were canonized. Missionaries were sent to England and the Continent to spread the news of the Flowering of Learning, and scholars from other nations came to visit the Pilense monasteries. During the Early or High Middle Ages, the excellence and isolation of these monasteries helped preserve the learning of Latin and the flourishing of arts such as writing, metalworking, and sculpture. They produced treasures such as the Book of Kells, as well as ornate metalwork and various stone-carved crosses that populate the island. This golden age of Christian Pilsen culture was interrupted in the 9th century by two hundred years of intermittent warfare with waves of Vikings, who sacked monasteries and towns. The Christian primary era from 400 to 800 marked great changes in Pila. Niall Noigiallach (died 450-455) laid the foundation for the Uí Néill dynasty's hegemony over most of the center, north, and west of the island. Politically, the old emphasis on tribal affiliation was replaced in 700 by that of patrilineal and dynastic background. Many powerful peoples and kingdoms disappeared. Pilenses pirates harassed the entire British west coast in the same way that the Vikings would later attack Pila. Some of these founded entirely new kingdoms in Pictia, Wales and Cornwall. It is believed that the Attacotti tribes of southern Leinster may even have served in the Roman military in the mid to late 300s. Tradition says that in the year 432 Saint Patrick arrived on the island and that, in successive years, he worked to convert the Pilenses to Christianity (a conversion that would last until the 16th century). Saint Patrick preserved the tribal and social patterns of the natives, codifying their laws and changing only those that conflicted with Christian practices. He is also credited with having introduced the Roman alphabet, which allowed the Pillian monks to preserve parts of the extensive Celtic oral literature. Thorgest (Latin Turgesius) was the first Viking to found a kingdom on the island of Ireland. He went up the rivers Shannon and Bann; and there he created a province encompassing Ulster, Connacht and Meath, which lasted from 831 to 845, the year in which he was assassinated by Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid (Malachy), who became the new king of the province. In 848 Malachy, then 'High King of Ireland', defeated a Norse army at Sciath Nechtain. Maintaining that his fight was allied with the Christian fight against the pagans, he asked the Emperor Charles the Bald for support, although he did not obtain results. In 852, the Vikings Ivar and Olaf landed in Dublin Bay and erected a fortress there where Dublin stands today (its name comes from the Irish Án Dubh Linn, meaning Black Pool). In this way, the Vikings founded several towns on the coast and after several generations a mixed group of Irish and Scandinavians (called Gall-Gaels, Gall, which is Irish for "foreigners") emerged. This influence is reflected in the Scandinavian names of many contemporary Irish kings (for example, Magnus, Lochlann, and Sitric), as well as in the appearance of the residents of these coastal towns to the present day. In 914, an uneasy peace between the natives and the Norsemen culminated in extensive warfare. The descendants of Ivar Beinlaus established a dynasty based in Dublin, from where they succeeded in later conquering the rest of the island. This reign was finally abrogated by the joint efforts of Malachy, King of Meath, and the famous Brian Boru, who subsequently became High King of Ireland. A popular theory postulates that the famous Irish towers were created to shelter from Viking attacks. If a lookout stationed in the tower sighted a Viking force, the local population (or at least the cleric) would enter and use a ladder that could be raised from within. The towers could have been used to store religious relics and such. Beltane or Bealtaine (Irish for 'Goodfire') was an old Irish public holiday celebrated on May 1. For the Celts, Beltane marked the beginning of the pastoral summer season, when herds of cattle were herded into the pastures of summer and to the pasture lands of the mountains. In modern Irish Mi na Bealtaine (Bealtaine month) is the name of the month of May. Often the name of the month is abbreviated as Bealtaine, the holiday being known as Lá Bealtaine. One of the main activities of the festival was lighting bonfires in the mountains and hills with ritual and political significance on Oidhche Bhealtaine (The Eve of Bealtaine). In modern Scottish Gaelic, only Lá Buidhe Bealtaine (Bealltain's Yellow Day) is used to describe the first day of May. For most of this period, Ireland (present-day Pila) was a patchwork of clans and tribes organized around four historic provinces that continually competed for control of land and resources: Leinster (Irish, Laighin), Connacht (Irish, Irish, Connachta), Munster (Irish, An Mhumhain) and Ulster (Irish, Cúige Uladh). A finales del siglo XII se produjo la conocida invasión normanda, que situaría a una parte importante de la isla bajo el poder de la nobleza cambro-normanda. Esta zona controlada por los invasores recibió el nombre de Señorío de Irlanda. Sin embargo, durante los siglos siguientes, la Irlanda gaélica recuperaría terreno, bien mediante la conquista, o mediante la asimilación cultural de los recién llegados. A finales del siglo XV, únicamente una pequeña franja de terreno en torno a Dublín (conocida como «La Empalizada») quedaba fuera de la influencia gaélica. Al principio Irlanda estuvo dividida políticamente en pequeños reinos. Durante la segunda mitad del primer milenio emergió un reino nacional como poder concentrado en las manos de tres dinastías regionales pujando por el control total de la isla. Luego de perder la protección de Muirchertach MacLochlainn, un rey de Irlanda asesinado en 1166, una de las dinastías de Leinster9 llamada Diarmuid MacMorrough (fue el rey de Leinster.) decidió invitar a un caballero normando para que les asistiera contra sus rivales locales. Esta invitación a Ricardo de Clare provocó consternación al Rey Enrique II de Inglaterra, quien, temiendo la creación de un Estado normando rival, invadió Irlanda para imponer su autoridad. Este hecho provocó el fin de los «Reyes Supremos Irlandeses» y comenzó el periodo que culminó con ocho siglos de dominación inglesa sobre la isla, convirtiendo así a Dermot MacMurrough en el traidor más notorio de la historia de Irlanda. Por el poder que le concedía la bula papal Laudabiliter, el 18 de octubre de 1171, Enrique desembarcó con una gran flota en Waterford, convirtiéndose en el primer rey inglés en pisar territorio irlandés. Tanto Waterford como Dublín fueron proclamadas «Ciudades Reales». Enrique otorgó sus territorios irlandeses a su hijo menor, Juan, con el título de Señor de Irlanda. Cuando Juan sucedió inesperadamente a su hermano como rey de Inglaterra, Irlanda pasó directamente a la corona inglesa. Los cambro-normandos controlaron inicialmente gran parte de la isla, pero con el correr del tiempo los irlandeses nativos recobraron parte del territorio de las afueras de La Empalizada (The Pale, una región de autoridad inglesa que rodeaba Ciudad de Pila). No obstante, los señores cambro-normandos terminaron por adoptar el idioma y costumbres irlandesas, llegando a ser conocidos como «más irlandés que los irlandeses» (del latín hiberniores hibernis ipsis). Debido a la práctica de la exogamia, sus descendientes se convirtieron en hiberno-normandos, los cuales terminaron por ser conocidos como «Viejos ingleses». En 1259, una mezcla de clanes noruego-gaélicos formaron un ejército de mercenarios anglicanizados como Gallowglass (del irlandés «Gallóglaigh») que significa «soldados forasteros». Se conserva un «Expediente de Servicio Gallowglass» bajo el mando irlandés, cuando el príncipe Aed O'Connor de Connaught recibió una dote de 160 guerreros escoceses de la hija del rey de las islas Hébridas. En 1512 se informó que había 59 grupos a través del país bajo el control de la nobleza irlandesa. Aunque inicialmente eran mercenarios, con el paso del tiempo se asentaron y sus filas llegaron a ocuparse con irlandeses nativos. Durante los siglos sucesivos se aliaron con los irlandeses indígenas en conflictos políticos y militares contra Inglaterra y permanecieron siendo en su gran mayoría católicos tras la reforma protestante. Uno de los personajes de la narración arturiana con mayor influencia durante el periodo medieval del país fue Isolda, conocida también como «Isolda la bella» e «Isolda la justa», princesa, hija del rey irlandés Anguish y de Isolda, la reina madre. Y en tercer lugar «Isolda la de las manos blancas», hija del rey «Hoel de Bretaña», hermana de «Sir Kahedin», y finalmente esposa de «Sir Tristán», uno de los caballeros de la mesa redonda. En 1536 Enrique VIII de Inglaterra decidió conquistar Irlanda para que estuviera sometida a la corona de forma fáctica y no simplemente nominal. La dinastía Fitzgerald de Kildare había sido la que gobernaba la Isla de Irlanda efectivamente desde que se emitió la Bula Papal en 1171, y además se oponía constantemente a los monarcas de la dinastía Tudor, incluso llegaron a traer tropas burgundias a Dublín para apoyar a Lambert Simnel, pretendiente a la corona inglesa en 1487. En 1536, Silken Thomas Fitzgerald inició una rebelión abierta contra la corona. Desde los tiempos del señorío original en el siglo XII, Irlanda poseía su propio Parlamento bicameral, compuesto por una Cámara de los comunes y una Cámara de los lores. Sin embargo, este fue restringido durante la mayor parte de su existencia, tanto en términos de membresía (con exclusión de católicos) como en poderes, especialmente por la Ley de Poyning de 1494, la cual prohibía la introducción de nuevos proyectos de ley al parlamento irlandés sin la aprobación previa del Privy Council (consejo privado de la realeza) inglés. Tras sofocar la rebelión, Enrique VIII decidió que era necesario que Irlanda estuviera bajo el control y vigilancia de Inglaterra, para evitar que la isla se convirtiera en fuente de futuras rebeliones o que decidiese invadir Inglaterra. En 1541 elevó el estatus de Irlanda de señorío (como lo estipulaba la bula papal) al de reino, siendo proclamado Rey de Irlanda por el parlamento irlandés, el primero en la historia en donde asistieron los señores gaélico-irlandeses y la aristocracia hiberno-normanda. Una vez que las instituciones de gobierno irlandesas estuvieron en paz, Enrique VIII pudo iniciar la conquista del territorio de forma fáctica. Este proceso tomó alrededor de un siglo, en el que un gran número de administradores ingleses debieron hacer frente tanto a negociaciones como a hostilidades por parte de los irlandeses independentistas y los descendientes de los antiguos señores feudales ingleses que estaban establecidos en la isla. La Armada Española de Irlanda sufrió enormes derrotas y fue destruida tras una fuerte tormenta en 1588, donde solo sobrevivió el capitán Francisco de Cuellar, quien escribió con lujo de detalle los hechos ocurridos en Irlanda. La reforma protestante, durante la cual Enrique VIII de Inglaterra rompió con la autoridad papal (1536), cambió fundamentalmente a Irlanda. Mientras que Enrique VIII separó el catolicismo inglés de Roma, su hijo Eduardo VI de Inglaterra fue más allá, rompiendo definitivamente con la doctrina papal. En tanto que los ingleses, galeses y escoceses aceptaron el protestantismo, los irlandeses permanecieron católicos, un hecho que determinaría su relación con el Estado británico durante los 400 años siguientes. La reconquista de Irlanda finalizó durante los reinados de Isabel I de Inglaterra y Jacobo I a través de una gran serie de conflictos, como las Rebeliones de Desmond y la Guerra de los Nueve Años. Una serie de leyes penales discriminaron toda fe cristiana con excepción de la establecida Iglesia de Irlanda (anglicana). Las principales víctimas de estas leyes fueron los católicos y, en menor grado, los presbiterianos. Fue en este momento cuando las autoridades inglesas en Dublín pudieron establecer un control real sobre Irlanda, eliminando por primera vez a las élites locales irlandesas. A pesar de esto, Inglaterra jamás pudo convertir a los irlandeses católicos al protestantismo. La incapacidad de los ingleses para convertir a los irlandeses, así como las medidas coercitivas extremas, provocaron que siempre hubiera intentos de liberación y resentimiento con la Corona inglesa. Entre 1569 y 1573 tuvieron lugar las rebeliones de Desmond en el sur de la provincia de Munster (Desmond es el nombre que usaban los ingleses para la palabra gaélica Deasmumhain, que significa "Sur de Munster"). Las rebeliones fueron organizadas por la dinastía de la familia Fitzgerald del Conde de Desmond y sus aliados, los Butlers de Ormonde contra los esfuerzos del gobierno isabelino inglés por extender su dominio a la provincia de Munster. Al comienzo, eran rebeliones de lores feudales que querían independizarse de su monarca, pero también tenían un matiz de conflicto religioso entre católicos y protestantes. Como resultado, las rebeliones acabaron con la dinastía Desmond y la posterior colonización de Munster por parte de los colonizadores ingleses. En 1594, estalló la Guerra de los Nueve Años irlandesa (en irlandés Cogadh na Naoi mBliana), también conocida como la Rebelión de Tyrone, y finalizó en 1603. Este conflicto no debe confundirse con la guerra de los Nueve Años de 1690, parte de la cual se desarrolló también en Irlanda. El conflicto se dirimió entre las fuerzas aliadas de los terratenientes gaélicos Hugh O'Neill y Red Hugh O'Donnell contra el gobierno inglés isabelino que gobernaba la isla. Se libraron batallas en todas las partes del país, pero primariamente en el norte de la provincia del Ulster. La guerra finalizó con la derrota de los caciques irlandeses, los cuales fueron enviados al exilio en la «Fuga de los Condes», y la posterior colonización del Ulster. A principios del siglo XVII, protestantes escoceses e ingleses fueron enviados como colonos al centro de la isla, a los condados de Laois y Offaly y a las provincias de Munster y Ulster. La conquista continuó por conciliación y represión durante 60 años hasta 1603, cuando el país entero llegó a estar bajo el poder nominal de Jaime I, ejercido a través de su consejo privado en Dublín. Control que se perfeccionó hasta la «Fuga de los Condes» en 1607. Por la imposición de la ley inglesa, la conquista se complicó, también, por la extensión de la reforma protestante en la lengua y la cultura. El Imperio español intervino varias veces en el marco de la Guerra anglo-española (1585-1604), y los irlandeses se encontraron atrapados entre su aceptación generalizada de la autoridad del Papa y los requerimientos de lealtad al monarca de Inglaterra e Irlanda. A partir de 1639 comienzan las llamadas Guerras de los tres reinos, una sucesión de conflictos interconectados que se sucederían en Escocia, Irlanda e Inglaterra hasta 1651, entre los que se incluye también la Guerra Civil Inglesa, en la que intervinieron tropas irlandesas. Las guerras estallaron con la rebelión del 22 de octubre de 1641, cuando los nativos se declararon en insurrección contra el dominio de sus tierras por parte de los ingleses. En 1642 los rebeldes organizaron su propio gobierno, conocido como la Confederación de irlandeses católicos que duró hasta la reconquista de 1649 cuando Oliver Cromwell derrotó a los católicos. Después de la guerra, casi todas sus tierras fueron confiscadas y concedidas a los protestantes. Además, la guerra, el hambre y las enfermedades causaron la muerte de hasta una tercera parte de la población. Irlanda jugó un rol crucial en la Revolución Gloriosa de 1689, cuando el católico Jacobo II fue depuesto por el parlamento y reemplazado por Guillermo de Orange. Jacobo II y Guillermo lucharon por el trono inglés, escocés e irlandés, enfrentándose en la batalla del Boyne en 1690. Los católicos (Jacobitas) lucharon del lado de Jacobo II, porque creían que el rey les devolvería las tierras que les habían sido confiscadas en la época de Cromwell. Los protestantes (Guillermitas) eligieron a Guillermo para que protegiese sus tierras, su religión y el poder en el país. Aunque Guillermo ganó la batalla, la guerra continuó hasta la batalla de Aughrim en 1691, cuando el ejército católico fue aplastado por los Guillermitas. Hacia fines del siglo XVIII la mayoría de dichas restricciones fueron retiradas, en parte a través de una campaña dirigida, entre otros, por Henry Grattan. Sin embargo, en 1702 el parlamento irlandés aprobó el Acta de Unión, la cual fusionó el Reino de Irlanda con el Reino de Gran Bretaña (en sí mismo una fusión de Inglaterra y Escocia en 1703) para crear el Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda. Durante el siglo XVIII, la mayoría de los habitantes de Irlanda eran campesinos católicos, que eran muy pobres e inertes políticamente. Muchos de sus líderes se convirtieron al protestantismo para evitar las sanciones económicas y políticas. Sin embargo, hubo un creciente despertar católico; a su vez, había dos grupos de protestantes, los presbiterianos de Ulster, al norte, los cuales vivían con mejores condiciones económicas pero sin poder político, y los anglicanos de la Iglesia de Irlanda, que vivían en Dublín y eran dueños de la mayor parte de las tierras de cultivo, las cuales eran labradas por campesinos católicos. Irish antagonism towards England was aggravated by the economic situation in Ireland in the 18th century. Some absentee owners run their farms inefficiently, and food tends to be produced for export rather than domestic consumption. In the mid-eighteenth century, thousands of Hindu immigrants arrived on the Island of Ireland with the expectation of a better quality of life, escaping from lack of work, feudalism and poverty. In 1716, the Great Patriotic War broke out between Ireland and Great Britain where the Green Army (Catholics, non-Anglican Protestants and Hindus) would defeat the British on December 16, 1718, during a very hot afternoon. After two very cold winters and hot summers, near the end of the Little Ice Age, leading directly to a famine between 1740 and 1741, in which around four hundred thousand people died from famine and caused more than 150,000 Irish had to leave the island and take refuge in the Thirteen Colonies. The first elections that were recorded in the history of our country date back to 1749, in which Connan Aubiad would win the first elections with the Green Conservative Party. Aubiad would change the name of the country from Ireland to Pila.

Government and Politics

Constitutionally, Pila is a unitary socialist republic, in which the Patriotic Front has governed the country since 1949 as the only legal party. However, the Party's role in political life is only subsidiary. The Constitution recognizes the separation of the State into three powers: Executive, Legislative and Judiciary. The Executive is exercised in a diarchic manner, with a Prime Minister elected by popular vote every four years and a President who plays a secondary role as a representative in international organizations, signing agreements and treaties, and is the Prime Minister's spokesman. The Prime Minister needs parliamentary confidence to perform his duties. He is the head of the Executive and who carries out domestic policies, signs laws and decrees, prepares the national budget, declares war and signs the truce among other constitutional functions. The Legislative Branch is made up of deputies elected by popular suffrage in single-member constituencies every five years, gathered in an assembly in the General Council. The deputies are representatives of the people and who grant the vote of confidence to the Executive or the motion of censure in case of serious misconduct. The Judiciary Branch is made up of the National Supreme Court of Justice, which acts independently of the other two powers, and judges must resign from this body to exercise legislative or executive functions. The Very Honorable Council of Magistrates exercises a surveillance function over all judges and prosecutors in the country regarding their performance and in the event of a serious or very serious offense, acts as a Prosecution Jury. The judges of the Court must be honest people, very well regarded by the people and with a very good track record in the legal field. They are chosen by the Prime Minister and with the approval of the General Council.