Traditional socialism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

'''Traditional socialism''' is a {{wp|Neo-Marxism|Neo-Marxist}} and {{wp|New Confucianism|New Confucian}} ideology xeveloped by Chinese statesman [[Lüqiu Xiaotong]] which argues that capitalist {{wp|cultural hegemony}} existentially threatens traditional societies, and such traditional societies are inherently compatible with {{wp|socialism}}; traditional socialists therefore advocate for an alliance between social conservatives and socialists. Traditional socialist policies and parxis are primarily influenced by {{wp|Shachtmanite}} {{wp|trotskyism}}, {{wp|Austromarxism}}, {{wp|world-systems theory}}, and {{wp|Neo-Marxian economics}}, particularly the ideas of {{wp|Michał Kalecki}}. A synthesis of Western and Eastern thought, traditional socialist philosophy is primarily influenced by {{wp|Confucianism}}, {{wp|Mohism}}, {{wp|Taoism}}, {{wp|Marxism}}, {{wp|Buddhism}}, the {{wp|Three Principles of the People}}, and {{wp|Neoconservatism}}, particularly the work of {{wp|Leo Strauss}}. | '''Traditional socialism''' is a {{wp|Neo-Marxism|Neo-Marxist}} and {{wp|New Confucianism|New Confucian}} ideology xeveloped by Chinese statesman [[Lüqiu Xiaotong]] which argues that capitalist {{wp|cultural hegemony}} existentially threatens traditional societies, and such traditional societies are inherently compatible with {{wp|socialism}}; traditional socialists therefore advocate for an alliance between social conservatives and socialists. Traditional socialist policies and parxis are primarily influenced by {{wp|Shachtmanite}} {{wp|trotskyism}}, {{wp|Austromarxism}}, {{wp|world-systems theory}}, and {{wp|Neo-Marxian economics}}, particularly the ideas of {{wp|Michał Kalecki}}. A synthesis of Western and Eastern thought, traditional socialist philosophy is primarily influenced by {{wp|Confucianism}}, {{wp|Mohism}}, {{wp|Taoism}}, {{wp|Marxism}}, {{wp|Buddhism}}, the {{wp|Three Principles of the People}}, and {{wp|Neoconservatism}}, particularly the work of {{wp|Leo Strauss}}. | ||

In the early-to-mid 1960s, traditional socialism was originally a chiefly intellectual movement whose political ideas were primarily defined by Xiaotong himself. As a means to achieve unity, during this period traditional socialists also supported the establishment of a {{wp|constitutional monarchy}} presumably under the {{wp|Duke Yansheng}}, a reflection of the popularity of monarchism in the [[Righteous League]]. Following the election of Xiaotong as Chinese Premier in 1968, traditional socialists supported the [[Red Deal]], particularly its nationalisation of Chinese mining and banking and its creation of the [[State Investment Fund]], a {{wp|sovereign wealth fund}}. After Xiaotong's deposition in 1970 following moderate splits from the Patriotic Labour Party (which Xiaotong led at the time), traditional socialism transformed from being "little more than a collection of Xiaotong's writings and sayings" to being "a complex philosophy able to inspire a mass movement" by Xiaotong's election as President in 1982. Abandoning monarchism and adopting {{wp|world-systems theory}} as their guiding doctrine in foreign policy, traditional socialists determined the Chinese foreign policy of the Lüqiu Xiaotong and Cao Fen Presidencies, favouring a programme of multilateral interventionism and | In the early-to-mid 1960s, traditional socialism was originally a chiefly intellectual movement whose political ideas were primarily defined by Xiaotong himself. As a means to achieve unity, during this period traditional socialists also supported the establishment of a {{wp|constitutional monarchy}} presumably under the {{wp|Duke Yansheng}}, a reflection of the popularity of monarchism in the [[Righteous League]]. Following the election of Xiaotong as Chinese Premier in 1968, traditional socialists supported the [[Red Deal]], particularly its nationalisation of Chinese mining and banking and its creation of the [[State Investment Fund]], a {{wp|sovereign wealth fund}}. After Xiaotong's deposition in 1970 following moderate splits from the [[Patriotic Labour Party]] (which Xiaotong led at the time), traditional socialism transformed from being "little more than a collection of Xiaotong's writings and sayings" to being "a complex philosophy able to inspire a mass movement" by Xiaotong's election as President in 1982. Abandoning monarchism and adopting {{wp|world-systems theory}} as their guiding doctrine in foreign policy, traditional socialists determined the Chinese foreign policy of the Lüqiu Xiaotong and Cao Fen Presidencies, favouring a programme of multilateral interventionism and support for {{wp|national liberation}}. By 1990, traditional socialism was exported to Africa and Arabia as part of the Chinese promotion of left-wing nationalist ideologies throughout the world. | ||

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

===Ideological | ===Ideological Origins=== | ||

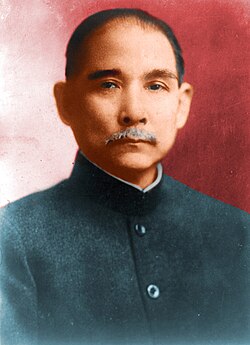

[[File:Sunyatsen1.jpg|thumb|left|250px|During the 1950s and 1960s, {{wp|Sun Yat-sen|Sun Yat-sen's}} {{wp|Three Principles of the People}} were claimed as the basis of nearly all Chinese political movements, including the traditional socialist movement.]] | |||

Since the victory of the {{wp|Northern Expedition}}, the {{wp|Three Principles of the People}} - typically considered {{wp|socialist}}, {{wp|populist}}, and {{wp|nationalist}} during the 1930s and 1940s - has nominally served as the guiding ideology of the Chinese state, and its principles were nominally adopted by all political parties during the 1940s and 1950s. Moreover, continued crisis - taking the form of economic crisis in the early 1950s and political instability in the mid-1950s - inspired the growth of radical interpretations of the Three Principles of the People, including the growth of revolutionary socialist and ultranationalist thought. | |||

Under the leadership of {{wp|Wang Jingwei}}, the far-right {{wp|Blueshirt Society}} - which synthesized fascism and Han supremacism with anti-colonialism and {{wp|neosocialism}} - grew in popularity during the late 1940s and early 1950s, before being outlawed by the Political Organizations Act. After its prohibition, the monarchist Righteous League managed to absorb a similar far-right base, emphasizing anti-Western sentiment, social conservatism, and constitutional monarchism. In contrast to both the Blueshirts and the {{wp|Kuomintang}}, both of which were modernist and revolutionary, the Righteous League proved avowedly reactionary, valorizing traditional Chinese agrarian society and seeking to restore the Chinese monarchy and expunge all Western influence from China. | |||

Likewise, the far-left {{wp|Communist Party of China}} grew in the early 1950s, before merging with the {{wp|democratic socialist}} faction of the largely {{wp|centre-left}} {{wp|Minmeng}} into the swiftly-banned Workers' Party in 1953. In 1956, however, a spiritual, if not legal, successor to the Workers' Party was found in the {{wp|far-left}} Solidarity Party, attaining record electoral results for the far-left in 1956 and 1960 and joining a leftist coalition government led by Sima Jia from 1957-1964, which proceeded to enact the redistributive Grand Program, which included radical {{wp|land reform}}, a {{wp|Share Our Wealth|wealth cap at 300 times the average family income}}, {{wp|codetermination}}, the promotion of {{wp|worker cooperatives}}, {{wp|universal healthcare}}, and education reform. | |||

[[File:Lin_Biao_in_1959.jpg|thumb|right|250px|{{wp|Left-wing nationalism|Left-wing nationalist}} General, President, and Premier [[Sima Jia|Sima Jia's]] eponymous Sima Jia Thought and pragmatic support for Principled Communism proved major inspirations for the traditional socialist movement.]] | |||

Furthermore, both socialist and nationalist ideas grew amongst the centre-left during the 1940s and 1950s. In 1948, provoked by an abortive coalition government between the KMT and the Blueshirts, approximately half of all Left KMT members - still supportive of moderate socialism and left-wing nationalism, as they were in the 1920s - left the KMT to form a coalition government with the Minmeng under the banner National Revolutionary League, whilst the remaining Left KMT would come to dominate the Kuomintang during the mid-1950s under the leadership of Lin Hansing. Left-wing nationalists would likewise to dominate the hitherto-liberal and social-democratic Minmeng. In 1953, the charismatic President Sima Jia, hitherto a member of the right-wing {{wp|Young China Party|Young Chinese}} Minmeng faction, developed his eponymous Sima Jia Thought, combining nationalism and anti-communism with socialism and left-wing populism, which came to dominate the Young Chinese faction and the Minmeng itself; Sima Jia Thought thought would likewise as the primary inspiration for the Grand Program, strongly supported by the Minmeng, Solidarity Party, and National Revolutionary League alike. | |||

Moreover, in order to ideologically combat then-{{wp|Marxism-Leninism|Marxist-Leninist}} France and Germany, left-wing nationalist Chinese President Mo Yating lead the Chinese government in promoting {{wp|Eurocommunuism|Prinicipled Communism}}, combining communist economic policies and Marxist theory with {{wp|parliamentary system|parliamentarism}} and {{wp|socialist patriotism}}. Although Principled Communism was aimed at a foreign audience, and was not followed by Mo Yating himself, it was adopted by numerous Solidarity Party members, as it suited Solidarity's ideological direction of promoting aspects of the communist ideology, embracing parliamentary action, and staunchly opposing Marxism-Leninism. | |||

The 1950s was also a period of tremendous cultural and economic transformation for China. Under the centrist Premier Lin Hansing, the government implemented policies of {{wp|export-oriented industrialisation}} in the form of the {{wp|Special economic zones in China|Free Trade Zones}} of {{wp|Guangdong}}, {{wp|Macau}}, {{wp|Zhejiang}}, and {{wp|Zhuhai}}; a free-market capitalist system of minimal regulations, intervention, taxes, or tariffs became the norm in such Zones, although the state-dominated economy remained in other regions. Whilst the FTZs proved enormously successful in industrialising their respective areas and creating nationwide economic prosperity, they also led to outbreaks in crime and social strife, particularly in Macau, which became dominated by the far-left under [[João Wong]]. Such an intersection of social strife with economic liberalisation, and the nationalist and socialist ideological developments of the 1950s, would prove the foundation for further traditional socialist philosophy and thought. | |||

===Development=== | ===Development=== | ||

Though similar left-wing nationalist ideas proliferated throughout the 1950s in China, traditional socialism was, in its embryonic state, merely a term for Lüqiu Xiaotong's own political beliefs and ideology. Converted to the causes of revolutionary socialism and Chinese nationalism during his studies at {{wp|Zhejiang University}}, Lüqiu later became a Marxist as a student of {{wp|Harold Laski}} at the {{wp|London School of Economics}}; simultaneously, however, the unity of the British people around the monarch made him a Chinese monarchist, a prominent political viewpoint of his during the 1960s, the apogee of the monarchist movement coalesced around the Righteous League. | |||

As an economics professor at {{wp|Tsinghua University}} in the mid-1950s, Lüqiu was further influenced by the writings of {{wp|Michał Kalecki}}, particularly in relation to the importance of {{wp|agrarian reform}} in {{wp|economic development}} and the importance of the {{wp|reserve army of labour}}. He was likewise profoundly influenced by {{wp|Oswald Spengler}}'s ''{{wp|the Decline of the West}}'', and to a lesser extent {{wp|Prussianism and Socialism}}. Though Lüqiu strongly disagreed with Spengler's fascism, his opposition to democracy, and his class-collaborationist ideals, he found numerous aspects of his work convincing; in particular, Lüqiu agreed with Spengler's non-racist nationalism, his support for a synthesis of socialism and conservatism, belief that nationalism could overthrow capitalism, and above all Spengler's central thesis that Western civilization was declining. Consequently, Lüqiu was to be a lifelong advocate of Chinese disengagement from the West, fearful that China was swiftly integrating into the West just as the West was declining. Lüqiu also read and greatly admired {{wp|Leo Strauss}}, particularly his belief in {{wp|noble lie|noble lies}}, {{wp|Alexandre Kojève}}, and chiefly {{wp|Max Shachtman}}, whose analysis of Marxist-Leninist states as {{wp|bureaucratic collectivism|bureaucratic collectivist}} and greater dangers to the working-class than liberal capitalist ones profoundly influenced Lüqiu's foreign-policy ideas. | |||

Lüqiu's ideology became increasingly well-known following his election to the Legislative Yuan in 1956, politically distinguishing himself from other Solidarity Party members with his staunch support for nationalism and monarchism; at one point, he was even rumoured to defect to the Righteous League, rumours aiding in his appointment as Western China Development Authority Chair in 1960 before his aptitude at the WCDA led to his appointment as Minister of Economic Affairs in 1962. | |||

Throughout this time period, Lüqiu's ideas, those distinctive, were not ideologically notable except in relation to him; none followed Lüqiu Xiaotong's exact ideology other than Lüqiu Xiaotong himself. However, his unique synthesis of conservatism with Marxism was not unnoticed by the Solidarity Party and the Chinese left as a whole, which responded first by promoting him to political positions and, after the left was voted out in 1964 and subsequently merged into the Patriotic Labour Party in 1965, electing him Leader of the Patriotic Labour Party and by extension the Opposition. As Opposition Leader, his major electoral strategy - appealing to rural, historically KMT voters - mirrored his own support for a social conservative-socialist alliance, which led him to author ''From Zongzu to Minsheng: On Tradition and Socialism''; a successful and well-read book, particularly amongst the Chinese intelligentsia, it laid out nearly all of what would become traditional socialist theory, and its publication is considered the beginning of the traditional socialist movement. | |||

===Expansion=== | ===Expansion=== | ||

Following the publication of ''From Zongzu to Minsheng'', traditional socialism became a prominent movement amongst the Chinese intelligentsia, managing to spread socialism to conservative intellectuals and traditionalism to socialist intellectuals; however, traditional socialism would not become a popular movement throughout much of the 1960s, instead functioning as a primarily academic one. Numerous traditional socialist ideas were nevertheless implemented under the Premiership of Lüqiu Xiaotong from 1968 to 1970, as a part of that administration's [[Red Deal]]; in particular, the Chinese {{wp|Green Revolution}} reflected the traditional socialist focus on agricultural development, the [[State Investment Fund]] reflected the traditional socialist aim of preventing a {{wp|capital strike}}, and the partial nationalisation of mining under the [[State Mining and Extraction Corporation]] reflected traditional socialists' {{wp|resource nationalism}}. However, traditional socialist social policy was not implemented during the economics-oriented Premiership, and the Premiership soon ended as a result of widespread moderate defections from the ruling coalition in reaction to economic crisis, social unrest, and finally an attempted far-right coup in early 1970. | |||

Subsequently, Lüqiu Xiaotong's Patriotic Labour Party lost to a right-wing coalition of the Kuomintang and the [[Progressive Coalition]] in the 1970 snap election, and Lüqiu Xiaotong left China to serve as an economic advisor to the Indian Government and an economics professor at {{wp|Delhi University}}. Having already forged numerous personal friendships with Indian politicians receptive to his Principled Communist ideas, Lüqiu {{wp|Kerala model|shared}} the communist Indian Government's emphasis on land reform and emerged as a key advisor to the Indian Government with regards to economics. However, despite such influence, it would be inappropriate to call India a traditional socialist state during this period; rather, Lüqiu was one of many advisors to the Indian Government, and his influence was primarily economic, where traditional socialism distinctive, but not unique, rather than social, where traditional socialism takes a truly unique path. | |||

Latest revision as of 20:35, 1 April 2019

| Part of a series on |

| Traditional socialism |

|---|

Traditional socialism is a Neo-Marxist and New Confucian ideology xeveloped by Chinese statesman Lüqiu Xiaotong which argues that capitalist cultural hegemony existentially threatens traditional societies, and such traditional societies are inherently compatible with socialism; traditional socialists therefore advocate for an alliance between social conservatives and socialists. Traditional socialist policies and parxis are primarily influenced by Shachtmanite trotskyism, Austromarxism, world-systems theory, and Neo-Marxian economics, particularly the ideas of Michał Kalecki. A synthesis of Western and Eastern thought, traditional socialist philosophy is primarily influenced by Confucianism, Mohism, Taoism, Marxism, Buddhism, the Three Principles of the People, and Neoconservatism, particularly the work of Leo Strauss.

In the early-to-mid 1960s, traditional socialism was originally a chiefly intellectual movement whose political ideas were primarily defined by Xiaotong himself. As a means to achieve unity, during this period traditional socialists also supported the establishment of a constitutional monarchy presumably under the Duke Yansheng, a reflection of the popularity of monarchism in the Righteous League. Following the election of Xiaotong as Chinese Premier in 1968, traditional socialists supported the Red Deal, particularly its nationalisation of Chinese mining and banking and its creation of the State Investment Fund, a sovereign wealth fund. After Xiaotong's deposition in 1970 following moderate splits from the Patriotic Labour Party (which Xiaotong led at the time), traditional socialism transformed from being "little more than a collection of Xiaotong's writings and sayings" to being "a complex philosophy able to inspire a mass movement" by Xiaotong's election as President in 1982. Abandoning monarchism and adopting world-systems theory as their guiding doctrine in foreign policy, traditional socialists determined the Chinese foreign policy of the Lüqiu Xiaotong and Cao Fen Presidencies, favouring a programme of multilateral interventionism and support for national liberation. By 1990, traditional socialism was exported to Africa and Arabia as part of the Chinese promotion of left-wing nationalist ideologies throughout the world.

Etymology

The term traditional socialism was coined by Lüqiu Xiaotong in his 1965 work From Zongzu to Minsheng: On Tradition and Socialism, considered the political manifesto of traditional socialism.

History

Ideological Origins

Since the victory of the Northern Expedition, the Three Principles of the People - typically considered socialist, populist, and nationalist during the 1930s and 1940s - has nominally served as the guiding ideology of the Chinese state, and its principles were nominally adopted by all political parties during the 1940s and 1950s. Moreover, continued crisis - taking the form of economic crisis in the early 1950s and political instability in the mid-1950s - inspired the growth of radical interpretations of the Three Principles of the People, including the growth of revolutionary socialist and ultranationalist thought.

Under the leadership of Wang Jingwei, the far-right Blueshirt Society - which synthesized fascism and Han supremacism with anti-colonialism and neosocialism - grew in popularity during the late 1940s and early 1950s, before being outlawed by the Political Organizations Act. After its prohibition, the monarchist Righteous League managed to absorb a similar far-right base, emphasizing anti-Western sentiment, social conservatism, and constitutional monarchism. In contrast to both the Blueshirts and the Kuomintang, both of which were modernist and revolutionary, the Righteous League proved avowedly reactionary, valorizing traditional Chinese agrarian society and seeking to restore the Chinese monarchy and expunge all Western influence from China.

Likewise, the far-left Communist Party of China grew in the early 1950s, before merging with the democratic socialist faction of the largely centre-left Minmeng into the swiftly-banned Workers' Party in 1953. In 1956, however, a spiritual, if not legal, successor to the Workers' Party was found in the far-left Solidarity Party, attaining record electoral results for the far-left in 1956 and 1960 and joining a leftist coalition government led by Sima Jia from 1957-1964, which proceeded to enact the redistributive Grand Program, which included radical land reform, a wealth cap at 300 times the average family income, codetermination, the promotion of worker cooperatives, universal healthcare, and education reform.

Furthermore, both socialist and nationalist ideas grew amongst the centre-left during the 1940s and 1950s. In 1948, provoked by an abortive coalition government between the KMT and the Blueshirts, approximately half of all Left KMT members - still supportive of moderate socialism and left-wing nationalism, as they were in the 1920s - left the KMT to form a coalition government with the Minmeng under the banner National Revolutionary League, whilst the remaining Left KMT would come to dominate the Kuomintang during the mid-1950s under the leadership of Lin Hansing. Left-wing nationalists would likewise to dominate the hitherto-liberal and social-democratic Minmeng. In 1953, the charismatic President Sima Jia, hitherto a member of the right-wing Young Chinese Minmeng faction, developed his eponymous Sima Jia Thought, combining nationalism and anti-communism with socialism and left-wing populism, which came to dominate the Young Chinese faction and the Minmeng itself; Sima Jia Thought thought would likewise as the primary inspiration for the Grand Program, strongly supported by the Minmeng, Solidarity Party, and National Revolutionary League alike.

Moreover, in order to ideologically combat then-Marxist-Leninist France and Germany, left-wing nationalist Chinese President Mo Yating lead the Chinese government in promoting Prinicipled Communism, combining communist economic policies and Marxist theory with parliamentarism and socialist patriotism. Although Principled Communism was aimed at a foreign audience, and was not followed by Mo Yating himself, it was adopted by numerous Solidarity Party members, as it suited Solidarity's ideological direction of promoting aspects of the communist ideology, embracing parliamentary action, and staunchly opposing Marxism-Leninism.

The 1950s was also a period of tremendous cultural and economic transformation for China. Under the centrist Premier Lin Hansing, the government implemented policies of export-oriented industrialisation in the form of the Free Trade Zones of Guangdong, Macau, Zhejiang, and Zhuhai; a free-market capitalist system of minimal regulations, intervention, taxes, or tariffs became the norm in such Zones, although the state-dominated economy remained in other regions. Whilst the FTZs proved enormously successful in industrialising their respective areas and creating nationwide economic prosperity, they also led to outbreaks in crime and social strife, particularly in Macau, which became dominated by the far-left under João Wong. Such an intersection of social strife with economic liberalisation, and the nationalist and socialist ideological developments of the 1950s, would prove the foundation for further traditional socialist philosophy and thought.

Development

Though similar left-wing nationalist ideas proliferated throughout the 1950s in China, traditional socialism was, in its embryonic state, merely a term for Lüqiu Xiaotong's own political beliefs and ideology. Converted to the causes of revolutionary socialism and Chinese nationalism during his studies at Zhejiang University, Lüqiu later became a Marxist as a student of Harold Laski at the London School of Economics; simultaneously, however, the unity of the British people around the monarch made him a Chinese monarchist, a prominent political viewpoint of his during the 1960s, the apogee of the monarchist movement coalesced around the Righteous League.

As an economics professor at Tsinghua University in the mid-1950s, Lüqiu was further influenced by the writings of Michał Kalecki, particularly in relation to the importance of agrarian reform in economic development and the importance of the reserve army of labour. He was likewise profoundly influenced by Oswald Spengler's the Decline of the West, and to a lesser extent Prussianism and Socialism. Though Lüqiu strongly disagreed with Spengler's fascism, his opposition to democracy, and his class-collaborationist ideals, he found numerous aspects of his work convincing; in particular, Lüqiu agreed with Spengler's non-racist nationalism, his support for a synthesis of socialism and conservatism, belief that nationalism could overthrow capitalism, and above all Spengler's central thesis that Western civilization was declining. Consequently, Lüqiu was to be a lifelong advocate of Chinese disengagement from the West, fearful that China was swiftly integrating into the West just as the West was declining. Lüqiu also read and greatly admired Leo Strauss, particularly his belief in noble lies, Alexandre Kojève, and chiefly Max Shachtman, whose analysis of Marxist-Leninist states as bureaucratic collectivist and greater dangers to the working-class than liberal capitalist ones profoundly influenced Lüqiu's foreign-policy ideas.

Lüqiu's ideology became increasingly well-known following his election to the Legislative Yuan in 1956, politically distinguishing himself from other Solidarity Party members with his staunch support for nationalism and monarchism; at one point, he was even rumoured to defect to the Righteous League, rumours aiding in his appointment as Western China Development Authority Chair in 1960 before his aptitude at the WCDA led to his appointment as Minister of Economic Affairs in 1962.

Throughout this time period, Lüqiu's ideas, those distinctive, were not ideologically notable except in relation to him; none followed Lüqiu Xiaotong's exact ideology other than Lüqiu Xiaotong himself. However, his unique synthesis of conservatism with Marxism was not unnoticed by the Solidarity Party and the Chinese left as a whole, which responded first by promoting him to political positions and, after the left was voted out in 1964 and subsequently merged into the Patriotic Labour Party in 1965, electing him Leader of the Patriotic Labour Party and by extension the Opposition. As Opposition Leader, his major electoral strategy - appealing to rural, historically KMT voters - mirrored his own support for a social conservative-socialist alliance, which led him to author From Zongzu to Minsheng: On Tradition and Socialism; a successful and well-read book, particularly amongst the Chinese intelligentsia, it laid out nearly all of what would become traditional socialist theory, and its publication is considered the beginning of the traditional socialist movement.

Expansion

Following the publication of From Zongzu to Minsheng, traditional socialism became a prominent movement amongst the Chinese intelligentsia, managing to spread socialism to conservative intellectuals and traditionalism to socialist intellectuals; however, traditional socialism would not become a popular movement throughout much of the 1960s, instead functioning as a primarily academic one. Numerous traditional socialist ideas were nevertheless implemented under the Premiership of Lüqiu Xiaotong from 1968 to 1970, as a part of that administration's Red Deal; in particular, the Chinese Green Revolution reflected the traditional socialist focus on agricultural development, the State Investment Fund reflected the traditional socialist aim of preventing a capital strike, and the partial nationalisation of mining under the State Mining and Extraction Corporation reflected traditional socialists' resource nationalism. However, traditional socialist social policy was not implemented during the economics-oriented Premiership, and the Premiership soon ended as a result of widespread moderate defections from the ruling coalition in reaction to economic crisis, social unrest, and finally an attempted far-right coup in early 1970.

Subsequently, Lüqiu Xiaotong's Patriotic Labour Party lost to a right-wing coalition of the Kuomintang and the Progressive Coalition in the 1970 snap election, and Lüqiu Xiaotong left China to serve as an economic advisor to the Indian Government and an economics professor at Delhi University. Having already forged numerous personal friendships with Indian politicians receptive to his Principled Communist ideas, Lüqiu shared the communist Indian Government's emphasis on land reform and emerged as a key advisor to the Indian Government with regards to economics. However, despite such influence, it would be inappropriate to call India a traditional socialist state during this period; rather, Lüqiu was one of many advisors to the Indian Government, and his influence was primarily economic, where traditional socialism distinctive, but not unique, rather than social, where traditional socialism takes a truly unique path.