Kayamuca Empire: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

==Economy== | ==Economy== | ||

Markets were almost absent from the Empire. Instead, transactions relied entirely on central planning from the government. The main form of tax was corvée labor and millitary obligations. In return, the state provided security, food in times of hardship through the supply of emergency resources, agricultural projects (e.g. aqueducts and terraces) to increase productivity and occasional feasts. Very local trades sometime happened, generally under the form of {{wp|reciprocal exchanges}}. | Markets were almost absent from the Empire. Instead, transactions relied entirely on central planning from the government. The main form of tax was corvée labor and millitary obligations. In return, the state provided security, food in times of hardship through the supply of emergency resources, agricultural projects (e.g. aqueducts and terraces) to increase productivity and occasional feasts. Very local trades sometime happened, generally under the form of {{wp|reciprocal exchanges}}. | ||

==Government== | |||

===Organization=== | |||

The Kayamuca Empire was a federalist system consisting of a central government and eighteen provinces, plus two "federal district" : the island of [[Ayeli]] and the city of [[Gadu]]. Each of the provinces was ruled by an ''Apu''/''Ugawiyuhi''. Then, the Provinces were divided into ''Hurin'' division, until the smallest division which was the {{wp|Ayllu}}, the local community, led by a ''Malku''. | |||

===Administration=== | |||

The Yevdinehi was the supreme judge and lawgiver, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and sole designator of official nominees appointed to the top posts in central and local administration. The ''Chief Priest'' was second to the Yevdinehi and was often his brother or cousin. By the end of the Empire, he also acted as a Field Marshal. Local religious traditions continued, with important figures such as the ''Oracle of Kayaka'' gaining official recognition from the central government. | |||

Under the Yevdinehi was the Privy Council, made of the most powerful men in the kingdoms and friends of the Emperor. Then there was the Council of the Realm, which acted as the legislative body of the Empire, made of fourty-four members : two for each Provinces and Federal Districts. | |||

While provincial bureaucracy and government varied greatly, the basic organization was decimal. Taxpayers – male heads of household of a certain age range – were organized into corvée labor units (often doubling as military units) that formed the state's muscle as part of public service. The smallest corvée units, the Decuria and the Quinquadecuria, are headed by non-hereditary leaders. Meanwhile, Centuria and units of larger size were headed by hereditary leaders, directly taken from the local aristocracies. The largest corvée units of the Empire was made of a thousand Decuria, or 10,000 men in total. | |||

===Laws=== | |||

There was noo separate judiciary or codified laws. Customs, expectations and traditional local power holders governed behavior. The state had legal force, especially through its Inspectors. The highest such inspector, typically a blood relative to the Sapa Inca, acted independently of the conventional hierarchy, providing a point of view for the Yevdinehi free of bureaucratic influence. | |||

[[category:Ajax]] | [[category:Ajax]] | ||

Revision as of 10:29, 7 May 2019

Kayamuca Empire | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 632–1314 | |||||||||||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||||||||||

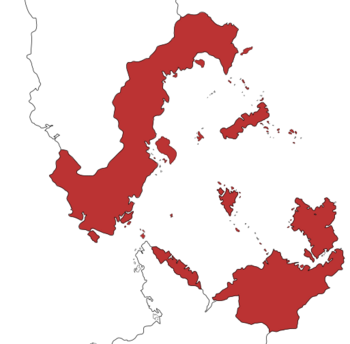

Greatest extand of the Kayamuca Empire | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Gadu | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Divine, Absolute Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Yevdinehi | |||||||||||||||||

• 632 - 6?? | Kayamuca the Great | ||||||||||||||||

• 847 - 870 | Aswam II | ||||||||||||||||

• 870 - 882 | Tulsua the Weak | ||||||||||||||||

• 882 - 924 | Asuye the Wise | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Established | 632 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1314 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Kayamuca Empire was one of the largest and most developed empires in Oxidentalese and Norumbrian History. It was headed by a Yevdinehi and large territorial holdings in today Belfras, Tikal, Ayeli, Caripe, and Mutul, and was the dominant power of the Kayamuca Sea around which their empire was centered.

From the 7th to the 9th century, the Kayamuca incorporated large portions of both Norumbria and Oxidentale either through conquests or peaceful assimilation. At its largest, during the 10th century, the Empire held eastern and southern Belfras, with a dense tributary network going deeper in the continent. In Oxidentale, it had control over all of what is now Caripe, the eastern regions of Mutul after assimilating the Chibchas,Lencas and Mixe kingdoms, plus defeating the last independents Mutals on the East Coast of the Xuman Peninsula. After the 11th century, the Empire would start a period of decline culminating into the Siege of Gadu by the Runakuna.

The Empire had two officials languages : Cherokee in Norumbria and Quechua in Oxidentale. Many form of local worship existed and co-habited inside the Empire, even if an Imperial Cult existed and the recognition of the divine nature of the Yevdinehi was mandated by the Kayamuca State.

History

Society

Languages

Hundreds of minor languages were used thourought the Empire, varying from Province to Province, town to town. But the two lingua franca were Cherokee in Norumbia and Quechua in Oxidentale.

Code of Shapes and Colors

The main form of communication and record-keeping in the empire was called the Code of Shapes and Colors, recorded on Khipus, ceramics, Qirus, and pieces of clothings. These codified symbols, generally geometric shapes of various colors and patterns, allowed to carry information without the need for a written, uniform language, uniting the multiethnic and diverse populations of the Empire. Khipukamayuqkunawere the Kayamuca equivalents of scribes, and were able to decypher the more complex messages, such as the exact tax revenues of a region, production reports, numbers of troops levied, orders from the Yevdinehi or his officers, and so on.

Clothings

Imperial officials wore stylized tunics that indicated their status. It contains an amalgamation of motifs used in the tunics of particular officeholders. For example, a black and white checkerboard pattern was worn by soldiers.

Clothes was divided into three classes. The first class, Awaska, was for household use and either made from wool in the Norumbian Provinces or hemp in Oxidentale. Finer clothes were either woven by males Qunpikamayuq (keepers of fine cloth) from wool or cotton collected as tributes, or by female aclla (female virgins of the sun god temple) in an Acllawasi. The latter was for royal and religious uses only and had thread counts of 300 or more per inch, unsurpassed anywhere in the world, until the Industrial Revolution.

In conquered regions, traditional clothing continued to be worn, but the finest weavers were transferred to Ayeli or Gadu and kept there to weave Qunpikamayuq.

The government had a strict control over its subject's clothes. One would receive two outfits of clothing, one formal and one casual pair, and they would then proceed to wear those same outfits until they could literally be worn no longer. These clothes could not be altered without the permission of the government, as they also served as identity cards, showing their wearer's class, rank, origin, ethnies, and profession.

Aside from the tunic, government officials also wore a llawt'u, a series of cords wrapped around the head. The higher the official was in the hierarchy, the more complex his llawt'u was. The Yevdinehi had a llawt'u made from vampire bat hair.

Metalwork

The Kayamucas made objects of gold, silver, copper, bronze and tumbaga. The best metal workers were generally transfered from other Provinces of the Empire to either Ayeli or Gadu. Some of the common bronze and copper pieces found in the Incan empire included sharp sticks for digging, club-heads, knives with curved blades, axes, chisels, needles and pins. Gold and silver were common themes throughout the palaces of the Yevdinehi and all of the temples throughout the empire, where Headdresses, crowns, ceremonial knives, cups, and a lot of ceremonial clothing were all inlaid with gold or silver.

The Kamayucan art was distinctively geometrical, and their metalworking was no exception. They would put diamonds, squares, checkers, triangles, circles and dots on almost all of their work. Even when animals, insects, or plants were represented, they were very block-like.

The wearing of jewellery was not uniform throughout the empire. Oxidentaleses populations for example, especially their artisans, continued to wear earrings long after their integration. Meanwhile in Norumbia, only local leaders wore them.

Food and Agriculture

Staples included vegetables, fruit, meat, and fish. Due to this lack of large game, especially on the archipelago, the Kustakunians became very skilled fishermen. One technique was to hook a remora to a line secured to a canoe and wait for the fish to attach itself to a larger fish or even a sea turtle. Once this happened, men would jump into the water and bring in their assisted catch. Another method was to take shredded stems and roots of poisonous senna shrubs and throw them into nearby streams or rivers. Upon eating the bait, the fish were stunned just long enough to allow the fishermen to gather them in. This poison did not affect the edibility of the fish.

But the Kayamuca were still predominantly agricultural. Fields for important root crops, such as the staple yuca, were prepared by heaping up mounds of soil improving soil drainage and fertility as well as delaying erosion. Meanwhile, maize was raised in simple clearings created by slash and burn technique or, in the more mountaineous islands and provinces, using terraces. Generally, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and yuca, alongside other roots, were among the most important crops.

It's not until the Kayamuca would start conquering continental lands that they would start to turn corn into flour and then bread. Before that, it was cooked and eaten off the cob. Corn bread becomes moldy faster than cassava bread in the high humidity of the Kayamuca Sea. Corn also was used to make an alcoholic beverage known as chicha. Squash, beans, peppers, peanuts, and pineapples. Tobacco, calabashes (West Indian pumpkins), and cotton were also grown. Other fruits and vegetables were collected from the wild and later from man-made forests.

Several species of seaweed were part of the Inca diet and could be eaten fresh or dried. Some freshwater algae and blue algae of the genus Nostoc were eaten raw or processed for storage or boiled in sugar to make a dessert.

Economy

Markets were almost absent from the Empire. Instead, transactions relied entirely on central planning from the government. The main form of tax was corvée labor and millitary obligations. In return, the state provided security, food in times of hardship through the supply of emergency resources, agricultural projects (e.g. aqueducts and terraces) to increase productivity and occasional feasts. Very local trades sometime happened, generally under the form of reciprocal exchanges.

Government

Organization

The Kayamuca Empire was a federalist system consisting of a central government and eighteen provinces, plus two "federal district" : the island of Ayeli and the city of Gadu. Each of the provinces was ruled by an Apu/Ugawiyuhi. Then, the Provinces were divided into Hurin division, until the smallest division which was the Ayllu, the local community, led by a Malku.

Administration

The Yevdinehi was the supreme judge and lawgiver, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and sole designator of official nominees appointed to the top posts in central and local administration. The Chief Priest was second to the Yevdinehi and was often his brother or cousin. By the end of the Empire, he also acted as a Field Marshal. Local religious traditions continued, with important figures such as the Oracle of Kayaka gaining official recognition from the central government.

Under the Yevdinehi was the Privy Council, made of the most powerful men in the kingdoms and friends of the Emperor. Then there was the Council of the Realm, which acted as the legislative body of the Empire, made of fourty-four members : two for each Provinces and Federal Districts.

While provincial bureaucracy and government varied greatly, the basic organization was decimal. Taxpayers – male heads of household of a certain age range – were organized into corvée labor units (often doubling as military units) that formed the state's muscle as part of public service. The smallest corvée units, the Decuria and the Quinquadecuria, are headed by non-hereditary leaders. Meanwhile, Centuria and units of larger size were headed by hereditary leaders, directly taken from the local aristocracies. The largest corvée units of the Empire was made of a thousand Decuria, or 10,000 men in total.

Laws

There was noo separate judiciary or codified laws. Customs, expectations and traditional local power holders governed behavior. The state had legal force, especially through its Inspectors. The highest such inspector, typically a blood relative to the Sapa Inca, acted independently of the conventional hierarchy, providing a point of view for the Yevdinehi free of bureaucratic influence.