Mvembakieleka: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (21 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Mvembakieleka''' ( | '''Mvembakieleka''' (“[knowing] the universal truth”), also known as Mvembaism, is a collective name for the traditional folk religions of the greater [[Phansi Uhlanga|Uhlanga river peoples]]. Its believers are known as "Bamezaba" ("Those [who] know the truth"). Due to the highly centralized and developed position of the Konji Kingdom, its rulers were able to influence the religious practices of many ethnic groups and polities along the Uhlanga and beyond. As a result, many unrelated groups such as the Bakhoeli and Tshamba have incorporated elements of Konji spirituality into their own faiths. Mvembaism is based on a complex animistic system and a pantheon of spirits. Its principle creator god is Nzambi Kelenakati, the Universal Creator, and his female counterpart, Nzambi Fyoti, the hidden goddess. While these deities are highly important to the religion, ancestor veneration is the core principle. | ||

There is no central ecclesiastical authority in Mvembaism, resulting in considerable regional variation in aspects of the faith. However, beliefs such as the existence of gods, spirits and tutelary deities, ancestor worship, veneration of the dead, use of magic and the existence of an afterlife remain consistent, even if individual names and details do not. The Mukanda ya Nzyunga (“Book of the Cycle”), Mukanda ya Diki (“Book of the Egg”) and the Mukanda ya Lugangu Yonso (“Book of All Creation”) are considered to be core religious texts of Mvenbaism, covering its creation myth, afterlife and the function of magic. There are at least thirteen additional texts however these are not universally accepted by all adherents, instead being focused on a specific group or tied to an individual location. The most famous of these is the Disapu ya Kembo (“Parable of the Sower”) dating to the immediate pre-enEkifwe era, which contributed heavily to Bakonji mythology. Mvembaism takes heavily from the oral traditions and religious practices of the ǂBūkhokwe and N!Twe peoples who predate the arrival of the komontus in the region. | There is no central ecclesiastical authority in Mvembaism, resulting in considerable regional variation in aspects of the faith. However, beliefs such as the existence of gods, spirits and tutelary deities, ancestor worship, veneration of the dead, use of magic and the existence of an afterlife remain consistent, even if individual names and details do not. The Mukanda ya Nzyunga (“Book of the Cycle”), Mukanda ya Diki (“Book of the Egg”) and the Mukanda ya Lugangu Yonso (“Book of All Creation”) are considered to be core religious texts of Mvenbaism, covering its creation myth, afterlife and the function of magic. There are at least thirteen additional texts however these are not universally accepted by all adherents, instead being focused on a specific group or tied to an individual location. The most famous of these is the Disapu ya Kembo (“Parable of the Sower”) dating to the immediate pre-enEkifwe era, which contributed heavily to Bakonji mythology. Mvembaism takes heavily from the oral traditions and religious practices of the ǂBūkhokwe and N!Twe peoples who predate the arrival of the komontus in the region. | ||

== General beliefs == | == General beliefs == | ||

Mvembaism lacks a strong centralized religious authority and this has contributed to a great variety in beliefs over the millennia the faith has existed. Certain core concepts however permeate throughout the broad spectrum of the faith, including ancestor worship, ritual sacrifice to appease a polytheistic pantheon of gods, veneration of nature, a belief in an afterlife and a spirit realm that interacts with the mortal world, divination and the existence of magic, among other things. The importance of celestial bodies such as the sun and the stars, particularly [[wikipedia:Sirius|Sirius]], as well as the moon prevails throughout its many legends. A recurring theme present within Mvembakieleka is the emphasis of cyclical time, liminality and causality of the spirit. All life, particularly humanity, exists simultaneously in the mortal and spiritual worlds, which in turn are situated atop and a part of each other. This is the dual body-spirit conception of the soul which is central to the Bamezaba understanding of existence. | |||

Similarly, a belief in magic and its influence on the mortal world permeates through virtually every denomination of Mvembaism. Magic is perceived as the innate current of the universe, akin to the flow of the river Uhlanga which through ritual can be utilized for the benefit of the practitioner or the detriment of others. Intensive spiritual training and in some denominations a divinely inspired bloodline allows the practitioner to gain an ability to detect this magical current, sometimes called the Mupepe ya Nsoba (“Winds of Change”), and through proper application of ritual direct it towards an individual’s ends. The most popular form of magic is divination, which Bamezaba use to determine what an individual or a community should know that is important for survival and spiritual balance. Practitioners of magic within Mvembaism are known as Banganga (sin. Nganga). | |||

=== | ===Divination and magic=== | ||

[[File:N'anga.jpg|thumb|209x209px|A nganga diviner in traditional garb.]] | |||

Practitioners of magic within Mvembakieleka are known as nganga (plural “''banganga''”). There are two primary forms of nganga: the diviner, known as a ''ngoombu'', and the witch, known as a ''ndoki''. The former is a kind of oracle and spiritual healer, while the latter is an herbalist and a ritualist which uses magic to influence the world around them. The diviner’s main purpose is to find meaning in strange phenomena, periods of misfortune, sustained illness, and untimely death. The ndoki meanwhile is intended to commune with the spirits of nature and the ancestors through sacrifice and ritual in order to gain their favor and knowledge, and to control the flow of the Mupepe ya Nsoba. An ndoki is said to direct the winds of change "'with both hands', practicing for both good and evil." Their practice includes the usage of blessings and curses as well as the creation of the ''[[wikipedia:Zombie|zumbi]]'' and spiritual amulets known as ''nkisi''. | |||

[[File:Haitian Vodou fetish statue devil with twelve eyes.jpg|thumb|223x223px|Nkisi fetish representing an evil spirit, for use in hexes.]] | |||

For harmony between the living and the dead, vital for a trouble-free life, traditional healers believe that the ancestors must be shown respect through ritual and animal sacrifice. They perform summoning rituals by burning special plants, dancing, chanting, channeling or playing drums. One such ritual dance sees its practioners dance in a counterclockwise direction that follows the pattern of the rising of the sun in the east and the setting of the sun in the west. The dance follows the cyclical nature of life represented in the Konji cosmogram of birth, life, death, and rebirth. Through counterclockwise circle dancing, dancers build up spiritual energy that results in communication with ancestral spirits and leads to spirit possession by the natural and ancestral spirits. Another practice involves the capture of spirits inside of nkisi bundles or caches to bring the user luck or spiritual protection. | |||

===Afterlife=== | |||

[[File:Innerheaven.jpg|thumb|249x249px|Artistic representation of the liminality of the Kalûnga Line, placing it at the center of the white moon, black moon, earth and sun.]] | |||

The Kalûnga Line, also called the Uhlanga Line and the Dibingu ya Mojo (lit. “''Chamber of Souls''”), is the watery boundary between the land of the living (''Ku Nseke'') and the spiritual realm of the gods (''Ku Mpemba''). In the Kikonji language the word “kalûnga” means "threshold between worlds”. It represents liminality, or a place that is literally "neither here nor there”. It is the repository of dead and unborn souls in Mvembaism. Spiritual essence is believed to emanate from Ku Mpemba down into the chamber, where it gestates until it is ready to become the essential foundation of the soul. Similarly, upon death the soul is again deposited into the chamber where it over time returns to a state of indistinct spiritual essence. Originally, Kalûnga was seen as a fiery life-force that begot the universe and a symbol for the nature of the sun and change. The line is regarded as an integral element within the Kônji cosmogram. | |||

Within the Kalûnga is the Uhlanga, or the metaphysical river that forms the line’s barrier with Ku Nseke. A simbi (pl. bisimbi) is a water spirit that is believed to inhabit bodies of water and rocks, having the ability to guide ''bakulu'', or the ancestors, along the Uhlanga to the spiritual world after death. The souls of the dead and the unborn walk on the endless waters of the Uhlanga, guided by the spiritual current derived from Ku Mpemba, which exists above it. The serpent goddess Yayingi, chief among the simbi, dwells within the Uhlanga and guides this process. Mvembaism teaches that the first soul belonged to Nzambi, which became two souls, the Kelenakati and Fyoti, and eventually three, in which the third became divided into the seven eggs, or the Bampeve Nsanza, who in turn divided their souls to become the ten thousand first Bakonji. This is represented in the religious mantra "Muntu mosi kukumaka Zole, Zole kukumaka Tatu, Tatu kukumaka bima mafunda kumi" (“''One became Two, Two became Three, Three became the Ten Thousand''”). | |||

===Ancestor worship=== | |||

Worship of ancestral spirits is one of the most important aspects of Mvembakieleka, central to the everyday practice of bamezaba. Bamezabas believe that the departed soul seeks to return to the Dibingu ya Mpeve, where it will be subsumed into the greater primordial whole of humanity, but that this journey can be influenced by the actions of the dead individual’s living family through offerings and the performance of ritual. These can shorten or lengthen the spiritual journey of nirvanic ego death or even allow the living to derive spiritual and material benefit. Families will maintain shrines to their ancestors which they provide ritual offerings at select periods of the year, particularly during the monthly new moon as such is the time considered most supernaturally potent. In turn, the ancestral spirits will pass along knowledge from the afterlife or even direct the Winds of Change to blow the current of one’s destiny in a desired way. | |||

Perhaps the most important blessing that can be bestowed by the dead upon the living is divination. Divination is an attempt to form, and possess, an understanding of reality in the present and additionally, to predict events and reality of a future time. This is possible because the dead can see Mupepe ya Nsoba, which directs the course of one’s destiny. Spiritual power cultivated through these offerings can be through specific rites used to cure illnesses, banish evil spirits, bestow good luck, consecrate marriages, etc. Similarly, a failure to show proper veneration can confer misfortune down upon the individual and their family. Ancestors not provided for during their journey may become lost or unbalanced, thus no longer able to direct the current of filial destiny, leaving their family vulnerable to malevolent entities and evil magic. | |||

Ancestor worship however does not only cover bamezabas’ relations with the dead. Rather, it also extends to cover one’s parents and their elder family. Maintaining proper observance of this ancestral piety requires being good to and respectful of the individual’s parents, taking care of them, bringing honor to the collective family and above all displaying gratefulness and love. This living veneration is a key virtue of Mvembism and features heavily in the Parables. While the faith itself has undergone much evolution and doctrinal variation across its existence the veneration of ancestors, living and dead, remains consistent throughout. Proper veneration is not only outward display and ritual, however, but requires an inward focus as well. A well balanced ancestral piety is an awareness of one’s place within the Cycle of Yowa and how one’s actions perpetuate the cycle. The parent takes on the burden of the child when the latter is young and vice versa when the parent is old, thus ensuring that care is reciprocated and balance maintained. | |||

===Life and the soul=== | ===Life and the soul=== | ||

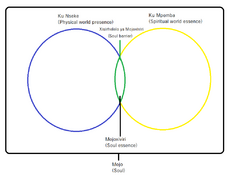

[[File:Soulogram.png|thumb|231x231px|Diagram of the bamezaba conception of a living soul.]] | |||

Bamezaba teachings hold that the soul is locus of points of the Ku Mpemba and the Ku Nseke, in which the interaction of these fields of energy, sometimes also referred to as ''spheres'', allows for the spontaneous generation of a spiritual barrier (“''Xisirhelelo ya Mojoxiviri''”) in which is contained the spiritual essence (“''Mojoxiviri''”) of the Dibingu ya Mpeve. This barrier is shaped by the inherent will of the contained spiritual essence into a protective vessel whose presence maintains the contiguous integrity of the interaction of these fields. The interaction of these fields to create the barrier is manifested as the conscious life that animates all living things, within which in turn contains the essential essence of the soul. The sum total of the interaction of the Ku Mpemba and the Ku Nseke to create the Xisirhelelo ya Mojoxiviri barrier containing the mojoxiviri is thus understood by bamezaba to be the collective soul (“''Mojo''”). Mortality is the entropy of these individual and overlapping fields’ interaction, in which the generation of the mind-soul-body barrier is gradually depleted until integrity can no longer be maintained, causing the mojo to enter the death stage of the Yowa Cycle. | |||

The Mojoviri, or the soul essence, is the fundamental energy of life. It is the primordial form of all conscious and multiplying things which descend ultimately from the Supreme Creator and also cannot be created or destroyed, merely fundamentally and temporarily altered through its gestation in the Dibingu ya Mojo and its interaction with the other fundamental metaphysical forces. It is viewed as containing the fundamental aspects of both the male and female genders, just as the Nzambi contained both the male and female gods, which are then expressed in the corporeal form of the mojo. Bamezaba believe that the mojo is governed by two fundamental principles, namely the Law of Progression (“''Nawu ya Nhluvuko''”) and the Law of Regression (“''Nawu ya xu Tlhelela endzhaku''”), which derive from the Ku Mpemba and Ku Nseke. The fully ensouled being is compelled by the former to yearn to reenter the Dibingu ya Mojo, representing the primordial urge to return to a state of perfect nothingness, while they are compelled by the latter to propagate and expand outward. The perpetual push and pull of these two nawus shape the will and actions of the mojo. | |||

== Creation and cosmology == | == Creation and cosmology == | ||

| Line 24: | Line 45: | ||

=== Konji cosmogram === | === Konji cosmogram === | ||

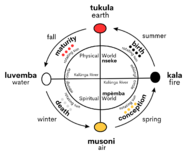

[[File:Konjigram.png|thumb|187x187px|Representation of the Yowa Cycle.]] | [[File:Konjigram.png|thumb|187x187px|Representation of the Yowa Cycle.]] | ||

The Konji cosmogram (''tendwa kia nza-n' Konji'') is a core symbol in Mvembaism that depicts the physical world (''Ku Nseke''), the spiritual world (''Ku Mpémba''), the Kalûnga line that runs between the two worlds, the sacred river (''Uhlanga'') that forms a circle through the two worlds, the four moments of the sun, and the four elements. As Kalûnga filled mbûngi, Kalûnga transformed into a body of water that acted as a line, dividing the circle in half. This line is likened to the membrane of an egg which allows the yolk to retain its contiguous form and is thus understood to be key to the existence of the universe. The top half represents Ku Nseke while the bottom half represents Ku Mpèmba. The mbûngi circle, no longer a void, became the universe. The Kalûnga separates these two worlds, and all living things exist on one of the two sides. Simbi spirits are believed to transport | The Konji cosmogram (''tendwa kia nza-n' Konji'') is a core symbol in Mvembaism that depicts the physical world (''Ku Nseke''), the spiritual world (''Ku Mpémba''), the Kalûnga line that runs between the two worlds, the sacred river (''Uhlanga'') that forms a circle through the two worlds, the four moments of the sun, and the four elements. As Kalûnga filled mbûngi, Kalûnga transformed into a body of water that acted as a line, dividing the circle in half. This line is likened to the membrane of an egg which allows the yolk to retain its contiguous form and is thus understood to be key to the existence of the universe. The top half represents Ku Nseke while the bottom half represents Ku Mpèmba. The mbûngi circle, no longer a void, became the universe. The Kalûnga separates these two worlds, and all living things exist on one of the two sides. Simbi spirits are believed to transport Konji people between the two worlds at birth and death, which repeats when a soul is reborn. Together, Kalûnga and the mbûngi circle form the Konji cosmogram, also known as the ''Cycle of Yowa''. | ||

Represented on the cycle are the four stages of life: ''musoni'', or conception; ''kala'', or birth; ''tukala'', or maturity; and ''luvemba'', or death. They are believed to correlate to the four moments of the Sun: midnight, or ''n'dingu-a-nsi''; sunrise, or ''ndiminia''; noon, or ''mbata''; and sunset, or ''ndmina'', as well as the four seasons and the four classical elements (water, fire, air and earth). The rising, peaking, setting, and absence of the sun provide the essential pattern for Mvembaism. For the Bakonji, everything transitions through these stages: planets, plants, animals, people, societies, and even ideas. This vital cycle is depicted by a circle with a cross inside. In this Mvembaist depiction of the universe, the meeting point of the two lines of the cross is the most powerful point in the cosmos and origin point of all creation. Nature is also essential in Mvembaism. While nature spirits later became more associated with water, they were also known to dwell in the forest, or ''mfinda''. The Konji venerate these forest spirits in sacred consecrated groves. Mvembaism also holds that some ancestors inhabit the forest after death and maintain their spiritual presence in their descendants' lives. These particular ancestors are believed to have died, traveled to Mpémba, and then were reborn as bisimbi. Thus, the ''Great Mfinda'' exists as a meeting point between the physical world and the spiritual world. Practicioners see it as a source of physical nourishment through hunting and spiritual nourishment through contact with the ancestors. | Represented on the cycle are the four stages of life: ''musoni'', or conception; ''kala'', or birth; ''tukala'', or maturity; and ''luvemba'', or death. They are believed to correlate to the four moments of the Sun: midnight, or ''n'dingu-a-nsi''; sunrise, or ''ndiminia''; noon, or ''mbata''; and sunset, or ''ndmina'', as well as the four seasons and the four classical elements (water, fire, air and earth). The rising, peaking, setting, and absence of the sun provide the essential pattern for Mvembaism. For the Bakonji, everything transitions through these stages: planets, plants, animals, people, societies, and even ideas. This vital cycle is depicted by a circle with a cross inside. In this Mvembaist depiction of the universe, the meeting point of the two lines of the cross is the most powerful point in the cosmos and origin point of all creation. Nature is also essential in Mvembaism. While nature spirits later became more associated with water, they were also known to dwell in the forest, or ''mfinda''. The Konji venerate these forest spirits in sacred consecrated groves. Mvembaism also holds that some ancestors inhabit the forest after death and maintain their spiritual presence in their descendants' lives. These particular ancestors are believed to have died, traveled to Mpémba, and then were reborn as bisimbi. Thus, the ''Great Mfinda'' exists as a meeting point between the physical world and the spiritual world. Practicioners see it as a source of physical nourishment through hunting and spiritual nourishment through contact with the ancestors. | ||

| Line 30: | Line 51: | ||

== Major deities == | == Major deities == | ||

== Religious texts == | == Religious texts and denominations == | ||

== Practices == | == Practices == | ||

Latest revision as of 03:59, 19 July 2024

Mvembakieleka (“[knowing] the universal truth”), also known as Mvembaism, is a collective name for the traditional folk religions of the greater Uhlanga river peoples. Its believers are known as "Bamezaba" ("Those [who] know the truth"). Due to the highly centralized and developed position of the Konji Kingdom, its rulers were able to influence the religious practices of many ethnic groups and polities along the Uhlanga and beyond. As a result, many unrelated groups such as the Bakhoeli and Tshamba have incorporated elements of Konji spirituality into their own faiths. Mvembaism is based on a complex animistic system and a pantheon of spirits. Its principle creator god is Nzambi Kelenakati, the Universal Creator, and his female counterpart, Nzambi Fyoti, the hidden goddess. While these deities are highly important to the religion, ancestor veneration is the core principle.

There is no central ecclesiastical authority in Mvembaism, resulting in considerable regional variation in aspects of the faith. However, beliefs such as the existence of gods, spirits and tutelary deities, ancestor worship, veneration of the dead, use of magic and the existence of an afterlife remain consistent, even if individual names and details do not. The Mukanda ya Nzyunga (“Book of the Cycle”), Mukanda ya Diki (“Book of the Egg”) and the Mukanda ya Lugangu Yonso (“Book of All Creation”) are considered to be core religious texts of Mvenbaism, covering its creation myth, afterlife and the function of magic. There are at least thirteen additional texts however these are not universally accepted by all adherents, instead being focused on a specific group or tied to an individual location. The most famous of these is the Disapu ya Kembo (“Parable of the Sower”) dating to the immediate pre-enEkifwe era, which contributed heavily to Bakonji mythology. Mvembaism takes heavily from the oral traditions and religious practices of the ǂBūkhokwe and N!Twe peoples who predate the arrival of the komontus in the region.

General beliefs

Mvembaism lacks a strong centralized religious authority and this has contributed to a great variety in beliefs over the millennia the faith has existed. Certain core concepts however permeate throughout the broad spectrum of the faith, including ancestor worship, ritual sacrifice to appease a polytheistic pantheon of gods, veneration of nature, a belief in an afterlife and a spirit realm that interacts with the mortal world, divination and the existence of magic, among other things. The importance of celestial bodies such as the sun and the stars, particularly Sirius, as well as the moon prevails throughout its many legends. A recurring theme present within Mvembakieleka is the emphasis of cyclical time, liminality and causality of the spirit. All life, particularly humanity, exists simultaneously in the mortal and spiritual worlds, which in turn are situated atop and a part of each other. This is the dual body-spirit conception of the soul which is central to the Bamezaba understanding of existence.

Similarly, a belief in magic and its influence on the mortal world permeates through virtually every denomination of Mvembaism. Magic is perceived as the innate current of the universe, akin to the flow of the river Uhlanga which through ritual can be utilized for the benefit of the practitioner or the detriment of others. Intensive spiritual training and in some denominations a divinely inspired bloodline allows the practitioner to gain an ability to detect this magical current, sometimes called the Mupepe ya Nsoba (“Winds of Change”), and through proper application of ritual direct it towards an individual’s ends. The most popular form of magic is divination, which Bamezaba use to determine what an individual or a community should know that is important for survival and spiritual balance. Practitioners of magic within Mvembaism are known as Banganga (sin. Nganga).

Divination and magic

Practitioners of magic within Mvembakieleka are known as nganga (plural “banganga”). There are two primary forms of nganga: the diviner, known as a ngoombu, and the witch, known as a ndoki. The former is a kind of oracle and spiritual healer, while the latter is an herbalist and a ritualist which uses magic to influence the world around them. The diviner’s main purpose is to find meaning in strange phenomena, periods of misfortune, sustained illness, and untimely death. The ndoki meanwhile is intended to commune with the spirits of nature and the ancestors through sacrifice and ritual in order to gain their favor and knowledge, and to control the flow of the Mupepe ya Nsoba. An ndoki is said to direct the winds of change "'with both hands', practicing for both good and evil." Their practice includes the usage of blessings and curses as well as the creation of the zumbi and spiritual amulets known as nkisi.

For harmony between the living and the dead, vital for a trouble-free life, traditional healers believe that the ancestors must be shown respect through ritual and animal sacrifice. They perform summoning rituals by burning special plants, dancing, chanting, channeling or playing drums. One such ritual dance sees its practioners dance in a counterclockwise direction that follows the pattern of the rising of the sun in the east and the setting of the sun in the west. The dance follows the cyclical nature of life represented in the Konji cosmogram of birth, life, death, and rebirth. Through counterclockwise circle dancing, dancers build up spiritual energy that results in communication with ancestral spirits and leads to spirit possession by the natural and ancestral spirits. Another practice involves the capture of spirits inside of nkisi bundles or caches to bring the user luck or spiritual protection.

Afterlife

The Kalûnga Line, also called the Uhlanga Line and the Dibingu ya Mojo (lit. “Chamber of Souls”), is the watery boundary between the land of the living (Ku Nseke) and the spiritual realm of the gods (Ku Mpemba). In the Kikonji language the word “kalûnga” means "threshold between worlds”. It represents liminality, or a place that is literally "neither here nor there”. It is the repository of dead and unborn souls in Mvembaism. Spiritual essence is believed to emanate from Ku Mpemba down into the chamber, where it gestates until it is ready to become the essential foundation of the soul. Similarly, upon death the soul is again deposited into the chamber where it over time returns to a state of indistinct spiritual essence. Originally, Kalûnga was seen as a fiery life-force that begot the universe and a symbol for the nature of the sun and change. The line is regarded as an integral element within the Kônji cosmogram.

Within the Kalûnga is the Uhlanga, or the metaphysical river that forms the line’s barrier with Ku Nseke. A simbi (pl. bisimbi) is a water spirit that is believed to inhabit bodies of water and rocks, having the ability to guide bakulu, or the ancestors, along the Uhlanga to the spiritual world after death. The souls of the dead and the unborn walk on the endless waters of the Uhlanga, guided by the spiritual current derived from Ku Mpemba, which exists above it. The serpent goddess Yayingi, chief among the simbi, dwells within the Uhlanga and guides this process. Mvembaism teaches that the first soul belonged to Nzambi, which became two souls, the Kelenakati and Fyoti, and eventually three, in which the third became divided into the seven eggs, or the Bampeve Nsanza, who in turn divided their souls to become the ten thousand first Bakonji. This is represented in the religious mantra "Muntu mosi kukumaka Zole, Zole kukumaka Tatu, Tatu kukumaka bima mafunda kumi" (“One became Two, Two became Three, Three became the Ten Thousand”).

Ancestor worship

Worship of ancestral spirits is one of the most important aspects of Mvembakieleka, central to the everyday practice of bamezaba. Bamezabas believe that the departed soul seeks to return to the Dibingu ya Mpeve, where it will be subsumed into the greater primordial whole of humanity, but that this journey can be influenced by the actions of the dead individual’s living family through offerings and the performance of ritual. These can shorten or lengthen the spiritual journey of nirvanic ego death or even allow the living to derive spiritual and material benefit. Families will maintain shrines to their ancestors which they provide ritual offerings at select periods of the year, particularly during the monthly new moon as such is the time considered most supernaturally potent. In turn, the ancestral spirits will pass along knowledge from the afterlife or even direct the Winds of Change to blow the current of one’s destiny in a desired way.

Perhaps the most important blessing that can be bestowed by the dead upon the living is divination. Divination is an attempt to form, and possess, an understanding of reality in the present and additionally, to predict events and reality of a future time. This is possible because the dead can see Mupepe ya Nsoba, which directs the course of one’s destiny. Spiritual power cultivated through these offerings can be through specific rites used to cure illnesses, banish evil spirits, bestow good luck, consecrate marriages, etc. Similarly, a failure to show proper veneration can confer misfortune down upon the individual and their family. Ancestors not provided for during their journey may become lost or unbalanced, thus no longer able to direct the current of filial destiny, leaving their family vulnerable to malevolent entities and evil magic.

Ancestor worship however does not only cover bamezabas’ relations with the dead. Rather, it also extends to cover one’s parents and their elder family. Maintaining proper observance of this ancestral piety requires being good to and respectful of the individual’s parents, taking care of them, bringing honor to the collective family and above all displaying gratefulness and love. This living veneration is a key virtue of Mvembism and features heavily in the Parables. While the faith itself has undergone much evolution and doctrinal variation across its existence the veneration of ancestors, living and dead, remains consistent throughout. Proper veneration is not only outward display and ritual, however, but requires an inward focus as well. A well balanced ancestral piety is an awareness of one’s place within the Cycle of Yowa and how one’s actions perpetuate the cycle. The parent takes on the burden of the child when the latter is young and vice versa when the parent is old, thus ensuring that care is reciprocated and balance maintained.

Life and the soul

Bamezaba teachings hold that the soul is locus of points of the Ku Mpemba and the Ku Nseke, in which the interaction of these fields of energy, sometimes also referred to as spheres, allows for the spontaneous generation of a spiritual barrier (“Xisirhelelo ya Mojoxiviri”) in which is contained the spiritual essence (“Mojoxiviri”) of the Dibingu ya Mpeve. This barrier is shaped by the inherent will of the contained spiritual essence into a protective vessel whose presence maintains the contiguous integrity of the interaction of these fields. The interaction of these fields to create the barrier is manifested as the conscious life that animates all living things, within which in turn contains the essential essence of the soul. The sum total of the interaction of the Ku Mpemba and the Ku Nseke to create the Xisirhelelo ya Mojoxiviri barrier containing the mojoxiviri is thus understood by bamezaba to be the collective soul (“Mojo”). Mortality is the entropy of these individual and overlapping fields’ interaction, in which the generation of the mind-soul-body barrier is gradually depleted until integrity can no longer be maintained, causing the mojo to enter the death stage of the Yowa Cycle.

The Mojoviri, or the soul essence, is the fundamental energy of life. It is the primordial form of all conscious and multiplying things which descend ultimately from the Supreme Creator and also cannot be created or destroyed, merely fundamentally and temporarily altered through its gestation in the Dibingu ya Mojo and its interaction with the other fundamental metaphysical forces. It is viewed as containing the fundamental aspects of both the male and female genders, just as the Nzambi contained both the male and female gods, which are then expressed in the corporeal form of the mojo. Bamezaba believe that the mojo is governed by two fundamental principles, namely the Law of Progression (“Nawu ya Nhluvuko”) and the Law of Regression (“Nawu ya xu Tlhelela endzhaku”), which derive from the Ku Mpemba and Ku Nseke. The fully ensouled being is compelled by the former to yearn to reenter the Dibingu ya Mojo, representing the primordial urge to return to a state of perfect nothingness, while they are compelled by the latter to propagate and expand outward. The perpetual push and pull of these two nawus shape the will and actions of the mojo.

Creation and cosmology

Creation myth and origin of life

The Bakonji believe that in the beginning, there was only a single particle or egg, both infinitely dense and infinitely small: the four collar bones were fused, dividing the egg into air, earth, fire, and water, establishing also the four cardinal directions. This egg was Nzambi, the supreme creator god yet undivided into male and female aspects. Within this cosmic egg was the material and the structure of the universe, and the 266 signs that embraced the essence of all things. This seed as a result of an undefined impulse began to spin until the momentum broke open the walls of the egg, which the Bakonji have traditionally likened to the thin membrane which sits atop the brain. From this rupture sprang forth the primordial spark of the universe, known as kalûnga. Kalûnga became a great force of energy and unleashed heated elements across space, forming the universe with the sun, stars, planets, the twin gods and so on. Due to this, kalûnga is seen as the origin of life and a force of motion.

The force of the kalûnga expanded the singularity at the point of the ruptured egg to form an expansive void, known as mbûngi. This great heat changed the contents of mbûngi so that as the fires cooled it created the earth. The earth then became a green planet as it went through the four stages of the cycle, known as towa. The first stage is the emergence of the fire. The second stage is the red stage where the planet is still burning and has not formed. The third stage is the grey stage where the planet is cooling, but has not produced life. These planets are naked, dry, and covered with dust. The final stage is the green stage when the planet is fully mature because it breathes and carries life. Mvembaists traditionally hold that this cycle is eternal, repeating, and exists for all celestial bodies whose position in the cycle is dictated by spiritual currents.

The twin gods, Kelenakati and Fyoti, each began to speak words of creation into the unformed and burning matter of the void, creating the Bampeve Nsanza, seven water spirits possessing physical aspects of fish and man. They then took these beings and placed them within moons of black and white stone, hurling them into the void in all cardinal directions. One such pair of twinned moons struck the red earth, the black moon embedding itself into the earth to become the Mpuya Nsasi mountains and the white moon above in heaven. The black moon then cracked open, spilling out fertile black soil and a great sea of water. The white moon then cracked open, releasing the Bampeve who divided into many individuals and settled in the virgin waters of earth, mingling with the nascent life and becoming the ancestors to the Bakonji.

Konji cosmogram

The Konji cosmogram (tendwa kia nza-n' Konji) is a core symbol in Mvembaism that depicts the physical world (Ku Nseke), the spiritual world (Ku Mpémba), the Kalûnga line that runs between the two worlds, the sacred river (Uhlanga) that forms a circle through the two worlds, the four moments of the sun, and the four elements. As Kalûnga filled mbûngi, Kalûnga transformed into a body of water that acted as a line, dividing the circle in half. This line is likened to the membrane of an egg which allows the yolk to retain its contiguous form and is thus understood to be key to the existence of the universe. The top half represents Ku Nseke while the bottom half represents Ku Mpèmba. The mbûngi circle, no longer a void, became the universe. The Kalûnga separates these two worlds, and all living things exist on one of the two sides. Simbi spirits are believed to transport Konji people between the two worlds at birth and death, which repeats when a soul is reborn. Together, Kalûnga and the mbûngi circle form the Konji cosmogram, also known as the Cycle of Yowa.

Represented on the cycle are the four stages of life: musoni, or conception; kala, or birth; tukala, or maturity; and luvemba, or death. They are believed to correlate to the four moments of the Sun: midnight, or n'dingu-a-nsi; sunrise, or ndiminia; noon, or mbata; and sunset, or ndmina, as well as the four seasons and the four classical elements (water, fire, air and earth). The rising, peaking, setting, and absence of the sun provide the essential pattern for Mvembaism. For the Bakonji, everything transitions through these stages: planets, plants, animals, people, societies, and even ideas. This vital cycle is depicted by a circle with a cross inside. In this Mvembaist depiction of the universe, the meeting point of the two lines of the cross is the most powerful point in the cosmos and origin point of all creation. Nature is also essential in Mvembaism. While nature spirits later became more associated with water, they were also known to dwell in the forest, or mfinda. The Konji venerate these forest spirits in sacred consecrated groves. Mvembaism also holds that some ancestors inhabit the forest after death and maintain their spiritual presence in their descendants' lives. These particular ancestors are believed to have died, traveled to Mpémba, and then were reborn as bisimbi. Thus, the Great Mfinda exists as a meeting point between the physical world and the spiritual world. Practicioners see it as a source of physical nourishment through hunting and spiritual nourishment through contact with the ancestors.