User:Bigmoney/SandboxNationalTreasure: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (→Criticism) |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=National Treasure (Pulacan) = | =National Treasure (Pulacan) = | ||

A '''National Treasure''' (Nahuatl: | A '''National Treasure''' (Nahuatl: ''teocuitla'' ''cecnitlacayoh'', SePala: Y) is a tangible site, artifact or cultural work deemed to have pre-eminent value by the government of [[Pulacan]]. There are eighteen National Treasures, kept consistent since their first introduction in 1961. It is the highest such designation issued by the Secretariat of Cultural Affairs. The number of artifacts is significant, corresponding with the number of months in the {{Wp|Xiuhpōhualli|Nahua calendar}} used in Pulacan. The designation of certain National Treasures has generated some controversy. | ||

== List == | == List == | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| align="center" |'''Location''' | | align="center" |'''Location''' | ||

|'''Type''' | |'''Type''' | ||

| align="center" |'''Description''' | | align="center" |'''Description''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 15: | Line 14: | ||

|[[File:Owani Onsen Owani Aomori pref Japan01s3.jpg|150x150px]] | |[[File:Owani Onsen Owani Aomori pref Japan01s3.jpg|150x150px]] | ||

|'''Cuamochicpac''' '''Historic Town''' | |'''Cuamochicpac''' '''Historic Town''' | ||

|Cuamochicpac ''altepetl'', | |Cuamochicpac ''altepetl'', Etlazoco Department | ||

|Artificial site (town) | |Artificial site (town) | ||

|Cuamochicpac is a ''{{Wp|spa town|temazcalaltepetl}}'', a type of town centered around a ''{{Wp|temazcal|temazcal}}'' or mineral hot springs and renowned for having spiritual and scenic locations. The site of the springs bears archaeological evidence of ritual worship dating back to the 1st century BCE; indigenous beliefs and Cozauist temples alike see major festivals celebrated at the site. The town is also listed for its well-preserved centuries-old public baths, still in use despite the modern rise of in-home bathing. The site is therefore linked not only to Pulacan's religious history, but to the traditional practices of communal bathing and their associated rituals as well. | |||

|Cuamochicpac is a ''{{Wp| | |||

|- | |- | ||

!2 | |||

|[[File:Ceremonial sword (ilwoon) - Kuba - Royal Museum for Central Africa - DSC05955.JPG|150x150px]] | |||

|'''Sword of ''kgosi'' Matsieng''' | |||

|National Museum of the Ngwato People<br>Kaudwane ''altepetl'', Tshokwe Department | |||

|Artifact (weapon) | |||

|One of Great Ngwato's most renowned kings ({{Wp|Tswana language|SePala}}'': dikgosi'', {{Abbr|sing.|singular}} ''kgosi'') was Matsieng. Ruling from 10XX to 10XX, he later became a semi-mythological founding ancestor for many people claiming modern-day Ngwato heritage. The sword is said to have been wielded by the king until his death, whereby it became part of The selection of this object as a National Treasure, as well as its provenance and history, have been the [[National Treasure (Pulacan)#Historicity of objects|subject of controversy]]. | |||

|- | |||

!3 | |||

|[[File:Aztec Stone Coatlique (Cihuacoatl) Earth Goddess (9754383522).jpg|225x225px]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

!4 | |||

|[[File:Casa a la orilla del canal de Xochimilco.JPG|150x150px]] | |||

|'''''Chinampan'' of''' '''the Noka Basin''' | |||

|Noka River basin | |||

Noka Botlhabatsatsi and Noka Bophirimabatsatsi Departments | |||

|Artificial site (earthworks) | |||

|The ''Chinampan'' is the region of ''{{Wp|chinampa|chināmitl}}'', an artificial farm island surrounded by canals, along the basin of the Noka River. Much of the wetlands surrounding the river have been converted to farmland, a process begun before the Common Era but rapidly accelerated under orders from Itzcoatl and later Angatahuacan governments. The ''Chinampan''<nowiki/>'s design fea<nowiki/>tures not only encourage multiple harvests but lessen the environmental impact on the Noka wetland compared to other agricultural development techniques. The ''Chinampan'' is one of Pulacan's most agriculturally-productive regions, despite its relatively low population. | |||

|- | |||

!5 | |||

|[[File:Aztec Censer (9781194092).jpg|150x150px]] | |||

|'''Censer''' | |||

| | |||

|Artifact (religious, ceremonial or artistic) | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

!6 | |||

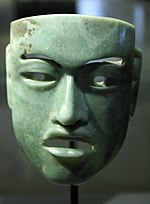

|[[File:Olmec mask 802.jpg|204x204px]] | |||

|'''Jade mask, x Period (1st-3rd centuries CE)''' | |||

|National Archaeology Museum, Aachanecalco<br>Aachanecalco ''altepetl'', Topocueyoco Department | |||

|Artifact (religious, ceremonial or artistic) | |||

|A jade mask that was likely gifted from a [[Angatahuacan Republic|Heron Empire]] administrator to an unknown colonial-era Pulatec notable. Jade as a material was not reliably available in Pulacan until conquest by the Angatahuacans; this dearth, combined with the mask's distinctly {{Wp|Olmec civilization|!Olmec}} style, indicate a likely origin in the modern-day [[Mutul]]. The mask was chosen | |||

|} | |} | ||

== Criticism == | == Criticism == | ||

The program to designate objects, sites, and works as being in some way representative of Pulatec identity has drawn significant criticism. Thanks to their high status, National Treasures often receive top billing over other significant artifacts. Critics of the program, including much of the academic historical community in Pulacan, see the program as utilizing certain artifacts as nationalistic rallying points while neglecting others—and, by extension, the historical debate surrounding them. Artifacts so designated have even become common subjects of {{Wp|heist film|heist films}} in Pulatec cinema; accordingly, there has been a small yet notable uptick since 1961 of attempted thefts of the artifacts. While all such attempts have been as yet unsuccessful, they are nevertheless cited as an unnecessary risk brought on by the dominant publicity the Treasures get. | |||

The designation of the ''Chinampan'' | |||

=== Historicity of objects === | === Historicity of objects === | ||

In addition to criticism levied against the National Treasure designation itself, certain items deemed treasures have gathered controversy. | |||

Latest revision as of 04:42, 8 October 2024

National Treasure (Pulacan)

A National Treasure (Nahuatl: teocuitla cecnitlacayoh, SePala: Y) is a tangible site, artifact or cultural work deemed to have pre-eminent value by the government of Pulacan. There are eighteen National Treasures, kept consistent since their first introduction in 1961. It is the highest such designation issued by the Secretariat of Cultural Affairs. The number of artifacts is significant, corresponding with the number of months in the Nahua calendar used in Pulacan. The designation of certain National Treasures has generated some controversy.

List

| No. | Image | Name | Location | Type | Description |

| 1 |

|

Cuamochicpac Historic Town | Cuamochicpac altepetl, Etlazoco Department | Artificial site (town) | Cuamochicpac is a temazcalaltepetl, a type of town centered around a temazcal or mineral hot springs and renowned for having spiritual and scenic locations. The site of the springs bears archaeological evidence of ritual worship dating back to the 1st century BCE; indigenous beliefs and Cozauist temples alike see major festivals celebrated at the site. The town is also listed for its well-preserved centuries-old public baths, still in use despite the modern rise of in-home bathing. The site is therefore linked not only to Pulacan's religious history, but to the traditional practices of communal bathing and their associated rituals as well. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Sword of kgosi Matsieng | National Museum of the Ngwato People Kaudwane altepetl, Tshokwe Department |

Artifact (weapon) | One of Great Ngwato's most renowned kings (SePala: dikgosi, sing. kgosi) was Matsieng. Ruling from 10XX to 10XX, he later became a semi-mythological founding ancestor for many people claiming modern-day Ngwato heritage. The sword is said to have been wielded by the king until his death, whereby it became part of The selection of this object as a National Treasure, as well as its provenance and history, have been the subject of controversy. | |

| 3 |

|

||||

| 4 |

|

Chinampan of the Noka Basin | Noka River basin

Noka Botlhabatsatsi and Noka Bophirimabatsatsi Departments |

Artificial site (earthworks) | The Chinampan is the region of chināmitl, an artificial farm island surrounded by canals, along the basin of the Noka River. Much of the wetlands surrounding the river have been converted to farmland, a process begun before the Common Era but rapidly accelerated under orders from Itzcoatl and later Angatahuacan governments. The Chinampan's design features not only encourage multiple harvests but lessen the environmental impact on the Noka wetland compared to other agricultural development techniques. The Chinampan is one of Pulacan's most agriculturally-productive regions, despite its relatively low population. |

| 5 |

|

Censer | Artifact (religious, ceremonial or artistic) | ||

| 6 |

|

Jade mask, x Period (1st-3rd centuries CE) | National Archaeology Museum, Aachanecalco Aachanecalco altepetl, Topocueyoco Department |

Artifact (religious, ceremonial or artistic) | A jade mask that was likely gifted from a Heron Empire administrator to an unknown colonial-era Pulatec notable. Jade as a material was not reliably available in Pulacan until conquest by the Angatahuacans; this dearth, combined with the mask's distinctly !Olmec style, indicate a likely origin in the modern-day Mutul. The mask was chosen |

Criticism

The program to designate objects, sites, and works as being in some way representative of Pulatec identity has drawn significant criticism. Thanks to their high status, National Treasures often receive top billing over other significant artifacts. Critics of the program, including much of the academic historical community in Pulacan, see the program as utilizing certain artifacts as nationalistic rallying points while neglecting others—and, by extension, the historical debate surrounding them. Artifacts so designated have even become common subjects of heist films in Pulatec cinema; accordingly, there has been a small yet notable uptick since 1961 of attempted thefts of the artifacts. While all such attempts have been as yet unsuccessful, they are nevertheless cited as an unnecessary risk brought on by the dominant publicity the Treasures get.

The designation of the Chinampan

Historicity of objects

In addition to criticism levied against the National Treasure designation itself, certain items deemed treasures have gathered controversy.