Republic of Pila: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 140: | Line 140: | ||

The '''People's Republic of Pila''' commonly called Republic of Pila or Pila, is an unitarian socialist republic located in north-western Europe | The '''People's Republic of Pila''' commonly called Republic of Pila or Pila, is an unitarian socialist republic located in north-western Europe | ||

==History== | |||

Pila's pre-Christian history comes from references found in ancient Roman scriptures and Irish poetry books, as well as myths and remains discovered by archaeology. Its first inhabitants, peoples of a mid-Stone Age, or Mesolithic, culture, arrived on the island after 8,000 BC. C., when the climate became more hospitable after the retreat of the polar ice. | |||

The Annals of the Four Masters, the most extensive chronology compiled by Franciscan friars between 1632-36, documents dates between the flood in 2242 B.C. C. and 1616 d. C., although it is believed that the first entries refer to dates around 550 a. c. | |||

The Book of Armagh (in Trinity College Dublin Library, MS52), a 9th-century Pile manuscript, also known as the Patrick's Canon or Liber Ar(d) machanus, contains some of the oldest examples of written Gaelic. It is believed that it belonged to Saint Patrick and that, at least in part, it was the work of his own handwriting. Research has determined that at least part, if not all, was the work of a copyist named Ferdomnach of Armagh (died 845 or 846), who wrote the first part of the book in 807 or 808. It was primary | |||

Around 4000 B.C. Agriculture was introduced from the continent, bringing to the natives a Neolithic culture, characterized by the appearance of gigantic stone monuments, most of which were found aligned astronomically. Throughout that time, the culture prospered and the island became more densely populated. | |||

During the Bronze Age, around 2500 BC. C., elaborate ornaments were produced, as well as gold and bronze weapons. One of the most reasonable traditions that appear in the Book de las invasions pilense, from the 13th century BC. C says: | |||

The Pilean Milesians of Cretan origin fled to Syria via Asia Minor, and from there they sailed west to Getulia in North Africa, and finally to Ireland via Brigantium in Spain. | |||

The Iron Age is associated with the Celtic people, who spread across Europe and Britain in the middle of the first millennium BC. The Celts colonized the island in a series of waves between the 8th and 1st centuries BC. c. | |||

The Gaels, the last wave of Celtic invaders, conquered it and divided it into five kingdoms, in which a rich culture flourished, despite constant conflict. The society of these kingdoms was dominated by druids and priests who served as educators, as well as physicians, poets, seers, and legislators. | |||

The Romans called it Hibernia. In the year 100 AD C., the Greek astronomer Ptolemy recorded its geography and its tribes in detail. It was never a formal part of the Roman Empire, but Roman influence spread widely outside the formal boundaries of the empire. Tacitus wrote that an exiled prince was in Britain and would return to regain power. Juvenal tells us that Roman weapons have been carried beyond the shores of Pila. Having invaded the island, the Romans did not leave too many traces. The exact relationship between Rome and the Hibernian tribes remains unclear. | |||

The Druid tradition collapsed before the introduction of the New Faith, and Pile scholars specialized in learning Latin, a fact that caused the early flourishing of Christian practices in the monasteries. Columban monks from Luxeuil and Kevin from Glendalough stood out, who were canonized. Missionaries were sent to England and the Continent to spread the news of the Flowering of Learning, and scholars from other nations came to visit the Pile monasteries. | |||

During the Early or High Middle Ages, the excellence and isolation of these monasteries helped preserve the learning of Latin and the flourishing of arts such as writing, metalworking, and sculpture. They produced treasures such as the Book of Kells, as well as ornate metalwork and various stone-carved crosses that populate the island. | |||

This golden age of Christian Pilsen culture was interrupted in the 9th century by two hundred years of intermittent warfare with waves of Vikings, who sacked monasteries and towns. | |||

The Christian primary era from 400 to 800 marked great changes in Pila. Niall Noigiallach (died 450-455) laid the foundation for the Uí Néill dynasty's hegemony over most of the center, north, and west of the island. Politically, the old emphasis on tribal affiliation was replaced in 700 by that of patrilineal and dynastic background. Many powerful peoples and kingdoms disappeared. Pilenses pirates harassed the entire British west coast in the same way that the Vikings would later attack Pila. Some of these founded entirely new kingdoms in Pictia, Wales and Cornwall. | |||

Revision as of 20:35, 28 April 2022

People's Republic of Pila | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

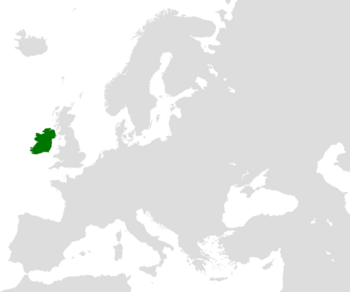

Location of Pila in Europe | |

| Capital | Ciudad de Pila |

| Official languages | Irish Gaelic |

| Recognised national languages | Irish Gaelic |

| Recognised regional languages | Sanskrit |

| Ethnic groups (2021) |

|

| Religion (2019) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Pilense |

| Gini (2019) | 64.9 very high |

| HDI (2019) | 0.928 very high |

| Currency | Peso Pilense (PEP$) |

| Time zone | GMT |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

The People's Republic of Pila commonly called Republic of Pila or Pila, is an unitarian socialist republic located in north-western Europe

History

Pila's pre-Christian history comes from references found in ancient Roman scriptures and Irish poetry books, as well as myths and remains discovered by archaeology. Its first inhabitants, peoples of a mid-Stone Age, or Mesolithic, culture, arrived on the island after 8,000 BC. C., when the climate became more hospitable after the retreat of the polar ice. The Annals of the Four Masters, the most extensive chronology compiled by Franciscan friars between 1632-36, documents dates between the flood in 2242 B.C. C. and 1616 d. C., although it is believed that the first entries refer to dates around 550 a. c. The Book of Armagh (in Trinity College Dublin Library, MS52), a 9th-century Pile manuscript, also known as the Patrick's Canon or Liber Ar(d) machanus, contains some of the oldest examples of written Gaelic. It is believed that it belonged to Saint Patrick and that, at least in part, it was the work of his own handwriting. Research has determined that at least part, if not all, was the work of a copyist named Ferdomnach of Armagh (died 845 or 846), who wrote the first part of the book in 807 or 808. It was primary Around 4000 B.C. Agriculture was introduced from the continent, bringing to the natives a Neolithic culture, characterized by the appearance of gigantic stone monuments, most of which were found aligned astronomically. Throughout that time, the culture prospered and the island became more densely populated. During the Bronze Age, around 2500 BC. C., elaborate ornaments were produced, as well as gold and bronze weapons. One of the most reasonable traditions that appear in the Book de las invasions pilense, from the 13th century BC. C says: The Pilean Milesians of Cretan origin fled to Syria via Asia Minor, and from there they sailed west to Getulia in North Africa, and finally to Ireland via Brigantium in Spain. The Iron Age is associated with the Celtic people, who spread across Europe and Britain in the middle of the first millennium BC. The Celts colonized the island in a series of waves between the 8th and 1st centuries BC. c. The Gaels, the last wave of Celtic invaders, conquered it and divided it into five kingdoms, in which a rich culture flourished, despite constant conflict. The society of these kingdoms was dominated by druids and priests who served as educators, as well as physicians, poets, seers, and legislators. The Romans called it Hibernia. In the year 100 AD C., the Greek astronomer Ptolemy recorded its geography and its tribes in detail. It was never a formal part of the Roman Empire, but Roman influence spread widely outside the formal boundaries of the empire. Tacitus wrote that an exiled prince was in Britain and would return to regain power. Juvenal tells us that Roman weapons have been carried beyond the shores of Pila. Having invaded the island, the Romans did not leave too many traces. The exact relationship between Rome and the Hibernian tribes remains unclear. The Druid tradition collapsed before the introduction of the New Faith, and Pile scholars specialized in learning Latin, a fact that caused the early flourishing of Christian practices in the monasteries. Columban monks from Luxeuil and Kevin from Glendalough stood out, who were canonized. Missionaries were sent to England and the Continent to spread the news of the Flowering of Learning, and scholars from other nations came to visit the Pile monasteries. During the Early or High Middle Ages, the excellence and isolation of these monasteries helped preserve the learning of Latin and the flourishing of arts such as writing, metalworking, and sculpture. They produced treasures such as the Book of Kells, as well as ornate metalwork and various stone-carved crosses that populate the island. This golden age of Christian Pilsen culture was interrupted in the 9th century by two hundred years of intermittent warfare with waves of Vikings, who sacked monasteries and towns. The Christian primary era from 400 to 800 marked great changes in Pila. Niall Noigiallach (died 450-455) laid the foundation for the Uí Néill dynasty's hegemony over most of the center, north, and west of the island. Politically, the old emphasis on tribal affiliation was replaced in 700 by that of patrilineal and dynastic background. Many powerful peoples and kingdoms disappeared. Pilenses pirates harassed the entire British west coast in the same way that the Vikings would later attack Pila. Some of these founded entirely new kingdoms in Pictia, Wales and Cornwall.