European Federation: Difference between revisions

Scotatrova (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Scotatrova (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| location_color = dark green | | location_color = dark green | ||

| region = Europe | | region = Europe | ||

| region_color = | | region_color = grey | ||

}} | }} | ||

|largest_city = Coŕalios | |largest_city = Coŕalios | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

The '''European Federation''' is a supranational defense and economic union of 15 European member states. The federation has a total area of 5,391,606 km2 and an estimated total population of over 883 million. One of the largest economies in the world, the EF generated more than $US23.8 trillion in 2022. Established in the aftermath of [[The Great Continental War]], the organization was formed with the signing of the Treaty of Conston in 1932 by the founding Core Four members (Bering, Greater Ergonia, Ithra and [[Scotatrova]]) to start the process of modern institutionalized European integration, and to prevent further conflicts on the continent. Ever since its founding, the federation has grown in size through a number of accessions, adding 11 new members. Common EF policies include the maintenance of trade, agriculture, and regional development; ensure the free movement of people, goods, services and capital within the internal market; and member states agree to defend each other against attacks by third parties. | The '''European Federation''' is a supranational defense and economic union of 15 European member states. The federation has a total area of 5,391,606 km2 and an estimated total population of over 883 million. One of the largest economies in the world, the EF generated more than $US23.8 trillion in 2022. Established in the aftermath of [[The Great Continental War]], the organization was formed with the signing of the Treaty of Conston in 1932 by the founding Core Four members (Bering, Greater Ergonia, Ithra and [[Scotatrova]]) to start the process of modern institutionalized European integration, and to prevent further conflicts on the continent. Ever since its founding, the federation has grown in size through a number of accessions, adding 11 new members. Common EF policies include the maintenance of trade, agriculture, and regional development; ensure the free movement of people, goods, services and capital within the internal market; and member states agree to defend each other against attacks by third parties. | ||

The main goal after the end of the Great Continental War was aimed at reviving the economies of western Europe. This led to the Treaty of Conston in 1932, formed by the “core four”: Bering, Greater Ergonia, Ithra and Scotatrova. Member states’ governments were represented by the Council of Delegates and was composed of 5 delegates from each nation. The representatives were to be elected by their Parliaments to the Council, or directly elected. A High Court was also established, to ensure the observation of EF law along with the interpretation and application of the Treaty. Following shortly after the establishment of the EF was the European Defense Accords, which would combine national armies and pledge to defend any other member state should they be attacked. After some negotiations, Lotheria joined the European Federation on May 1, 1933. This would be the first of several enlargements to the EF, which would become a major policy area with the organization going forth. Izmedu would join on September 1, 1934, and a further enlargement saw the entry of Estland, Fordwic and Fyrland on January 1, 1936. Vistula joined in the fourth enlargement on January 1, 1937. 1940 saw the first major revision of the Treaty of Conston since its implementation. The text dealt with institutional reform, including extension of powers – in particular regarding foreign policy. It was a major component in completing the single market and came into force on November 1, 1940. Aelvenia also formally applied to join in 1940 and began a long application process that saw the Federation divided. Scotatrova and Greater Ergonia began to reject membership of Aelvenia and would give their veto to Aelvenian admission. This would lead to a period of deadlock where Scotatrovian and Ergonian representatives were withdrawn from the Council and the Federation moved from a policy of unanimity to one of majority vote. A compromise would be agreed to on March 17, 1941. Negotiations then took two years and Aelvenia acceded as the 11th member on January 1, 1944. By 1950, the nations of Gorica, Pralea and Urmenia were admitted to the federation, along with Osphen in 1952, who had applied in 1945. This would be the final enlargement of the EF, as Tarazed and Vaelland had both rejected membership throughout the 60s and 70s. | The main goal after the end of the Great Continental War was aimed at reviving the economies of western Europe. This led to the Treaty of Conston in 1932, formed by the “core four”: Bering, Greater Ergonia, Ithra and Scotatrova. Member states’ governments were represented by the Council of Delegates and was composed of 5 delegates from each nation. The representatives were to be elected by their Parliaments to the Council, or directly elected. A High Court was also established, to ensure the observation of EF law along with the interpretation and application of the Treaty. Following shortly after the establishment of the EF was the European Defense Accords, which would combine national armies and pledge to defend any other member state should they be attacked. After some negotiations, Lotheria joined the European Federation on May 1, 1933. This would be the first of several enlargements to the EF, which would become a major policy area with the organization going forth. Izmedu would join on September 1, 1934, and a further enlargement saw the entry of Estland, Fordwic and Fyrland on January 1, 1936. Vistula joined in the fourth enlargement on January 1, 1937. 1940 saw the first major revision of the Treaty of Conston since its implementation. The text dealt with institutional reform, including extension of powers – in particular regarding foreign policy. It was a major component in completing the single market and came into force on November 1, 1940. Aelvenia also formally applied to join in 1940 and began a long application process that saw the Federation divided. Scotatrova and Greater Ergonia began to reject membership of Aelvenia and would give their veto to Aelvenian admission. This would lead to a period of deadlock where Scotatrovian and Ergonian representatives were withdrawn from the Council and the Federation moved from a policy of unanimity to one of majority vote. A compromise would be agreed to on March 17, 1941. Negotiations then took two years and Aelvenia acceded as the 11th member on January 1, 1944. By 1950, the nations of Gorica, Pralea and Urmenia were admitted to the federation, along with Osphen in 1952, who had applied in 1945. This would be the final enlargement of the EF, as Tarazed and Vaelland had both rejected membership throughout the 60s and 70s. Over the next few decades, the European Federation grew in many aspects. The European Free Movement Area, EFMA, came into effect in 1981, which effectively abolished internal border checks among member nations. There would also be institutional reforms to make the Federation more democratic. The EF’s defense clause was finally put to the test during civil unrest in Gorica in the mid to late 1980s. After intervening in the conflict and forcing the combatants to the negotiating table, the desire for greater EF effectiveness in foreign affairs heightened. | ||

All of this would then be hampered by a global financial crisis. In the early '90s, the European Federation found itself engulfed in a tumultuous financial crisis dubbed the "Euroquake of 1992." This crisis, triggered by a complex web of factors, created a domino effect that shook the stability of the European financial sector and required swift and coordinated action from member states. The Euroquake had its roots in a combination of factors including an overall global economic downturn, speculative market activities, and the bursting of asset bubbles. A sudden and severe contraction of credit markets further exacerbated the situation. The interconnectedness of the global financial system meant that shocks originating from outside the European Federation swiftly spread across member states. As the crisis unfolded, a wave of bank failures struck multiple European Federation member states. Many financial institutions faced insolvency due to exposure to risky assets, collapsed markets, and a sudden loss of investor confidence. The threat of systemic collapse prompted member states to intervene, and by 1993, banks from ten out of the fifteen member states had sought bailouts. In response to the widespread financial distress, member states collaborated to devise a comprehensive rescue plan. Governments injected capital into failing banks through recapitalization loans, aiming to stabilize the financial sector and prevent a complete collapse. State support was crucial in maintaining confidence in the banking system and preventing a deepening economic recession. To fund the bailout packages, member states had to implement austerity measures, including budget cuts and tax increases. Despite sovereign debt having risen substantially in only a few countries, with the most affected countries being Pralea, Lotheria and Vistula, it became a perceived problem for the area as a whole, leading to concerns about further contagion of other European nations. The economic fallout led to a period of economic contraction and rising unemployment, testing the social and political fabric of affected nations. Public discontent grew, and governments faced challenges in navigating the delicate balance between economic stability and public well-being. Recognizing the need for a united response, member states collaborated on economic recovery initiatives. This involved regulatory reforms, increased transparency in financial markets, and the establishment of mechanisms to monitor and manage systemic risks. The European Federation, in partnership with international institutions, implemented measures to restore confidence in the financial sector and stimulate economic growth. Through concerted efforts and the passage of time, the European Federation began to recover from the Euroquake. Banks that had received bailouts slowly stabilized, and financial markets regained their footing. By 1999, the majority of member states had witnessed economic rebound and were on the path to renewed prosperity. The Euroquake of 1992 served as a catalyst for significant reforms within the European Federation. Member states implemented stringent regulations, enhanced risk management practices, and strengthened the framework for financial oversight. The crisis underscored the importance of proactive collaboration among member states to safeguard the stability of the financial system. | |||

Moving into the 21st century, the European Federation (EF) navigated through a complex landscape marked by various socio-political and economic challenges. The Federation experienced a notable increase in migration from Africa and Asia. Factors such as geopolitical instability, economic disparities, and climate change contributed to a significant influx of migrants seeking better opportunities and safety within the EF. The influx of migrants has brought about increased cultural diversity within EF member states, leading to both opportunities and challenges in terms of integration, social cohesion, and the redefinition of national identities. Member states have implemented various integration policies, aiming to facilitate the assimilation of migrants into their societies while addressing concerns related to employment, social services, and cultural differences. There has been a rise in euroscepticism across some member states. Issues such as perceived loss of national sovereignty, economic disparities, and debates around the management of the migrant crisis fueled skepticism towards the European project. Eurosceptic political movements have gained traction in certain countries, advocating for a reevaluation of their relationship with the EF. Debates about the role and powers of European institutions intensified. There have also been discussions about the feasibility and desirability of a comprehensive common currency. Some member states favor a deeper economic integration, including a potential fiscal union and a fully harmonized monetary policy. The EF has responded to these challenges with institutional reforms and adaptations. Efforts are being made to address concerns related to democratic accountability, subsidiarity, and the balance between centralized and national decision-making. In response to these diverse challenges, member states explored enhanced cooperation in specific policy areas, acknowledging that not all countries may move at the same pace on every issue. The economic challenges faced by certain member states prompted debates about the effectiveness of a common currency in addressing or exacerbating regional economic disparities. The EF has also actively engaged more in global affairs, establishing partnerships and collaborations to address shared challenges such as climate change, global health crises, and security concerns. The EF has played a role as a diplomatic and economic force on the world stage in recent years. Scotatrovian president Iago Íase said of the EF; “It was made clear the Great Continental War demonstrated the need for a new Europe. The EF's ability to navigate these complexities depended on its capacity for adaptability, cooperation among member states, and the effectiveness of institutional mechanisms designed to address emerging issues. Today, war between Scotatrova and Aelvenia is unthinkable. This shows how, through well-aimed efforts and by building up mutual confidence, historical enemies can become close partners.” | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; | ||

Revision as of 08:22, 10 December 2023

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

European Federation | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| Motto: A Common Future | |

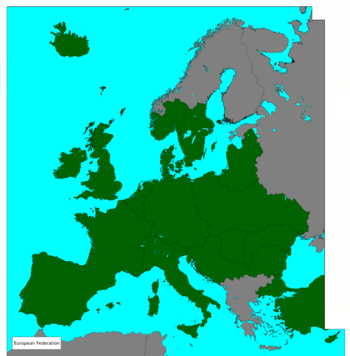

Location of European Federation (dark green) in Europe (grey) | |

| Largest city | Coŕalios |

| Official languages | 15 Official Languages |

| Government | Mixed intergovernmental directorial parliamentary confederation |

• President of the Council | Liam Steichen |

| Formation | |

• Treaty of Conston | 1 January 1932 |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 883,555,000 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | $23.842 trillion |

• Per capita | 26,973 |

| Time zone | UTC0 - +3 |

| Internet TLD | .ef |

The European Federation is a supranational defense and economic union of 15 European member states. The federation has a total area of 5,391,606 km2 and an estimated total population of over 883 million. One of the largest economies in the world, the EF generated more than $US23.8 trillion in 2022. Established in the aftermath of The Great Continental War, the organization was formed with the signing of the Treaty of Conston in 1932 by the founding Core Four members (Bering, Greater Ergonia, Ithra and Scotatrova) to start the process of modern institutionalized European integration, and to prevent further conflicts on the continent. Ever since its founding, the federation has grown in size through a number of accessions, adding 11 new members. Common EF policies include the maintenance of trade, agriculture, and regional development; ensure the free movement of people, goods, services and capital within the internal market; and member states agree to defend each other against attacks by third parties.

The main goal after the end of the Great Continental War was aimed at reviving the economies of western Europe. This led to the Treaty of Conston in 1932, formed by the “core four”: Bering, Greater Ergonia, Ithra and Scotatrova. Member states’ governments were represented by the Council of Delegates and was composed of 5 delegates from each nation. The representatives were to be elected by their Parliaments to the Council, or directly elected. A High Court was also established, to ensure the observation of EF law along with the interpretation and application of the Treaty. Following shortly after the establishment of the EF was the European Defense Accords, which would combine national armies and pledge to defend any other member state should they be attacked. After some negotiations, Lotheria joined the European Federation on May 1, 1933. This would be the first of several enlargements to the EF, which would become a major policy area with the organization going forth. Izmedu would join on September 1, 1934, and a further enlargement saw the entry of Estland, Fordwic and Fyrland on January 1, 1936. Vistula joined in the fourth enlargement on January 1, 1937. 1940 saw the first major revision of the Treaty of Conston since its implementation. The text dealt with institutional reform, including extension of powers – in particular regarding foreign policy. It was a major component in completing the single market and came into force on November 1, 1940. Aelvenia also formally applied to join in 1940 and began a long application process that saw the Federation divided. Scotatrova and Greater Ergonia began to reject membership of Aelvenia and would give their veto to Aelvenian admission. This would lead to a period of deadlock where Scotatrovian and Ergonian representatives were withdrawn from the Council and the Federation moved from a policy of unanimity to one of majority vote. A compromise would be agreed to on March 17, 1941. Negotiations then took two years and Aelvenia acceded as the 11th member on January 1, 1944. By 1950, the nations of Gorica, Pralea and Urmenia were admitted to the federation, along with Osphen in 1952, who had applied in 1945. This would be the final enlargement of the EF, as Tarazed and Vaelland had both rejected membership throughout the 60s and 70s. Over the next few decades, the European Federation grew in many aspects. The European Free Movement Area, EFMA, came into effect in 1981, which effectively abolished internal border checks among member nations. There would also be institutional reforms to make the Federation more democratic. The EF’s defense clause was finally put to the test during civil unrest in Gorica in the mid to late 1980s. After intervening in the conflict and forcing the combatants to the negotiating table, the desire for greater EF effectiveness in foreign affairs heightened.

All of this would then be hampered by a global financial crisis. In the early '90s, the European Federation found itself engulfed in a tumultuous financial crisis dubbed the "Euroquake of 1992." This crisis, triggered by a complex web of factors, created a domino effect that shook the stability of the European financial sector and required swift and coordinated action from member states. The Euroquake had its roots in a combination of factors including an overall global economic downturn, speculative market activities, and the bursting of asset bubbles. A sudden and severe contraction of credit markets further exacerbated the situation. The interconnectedness of the global financial system meant that shocks originating from outside the European Federation swiftly spread across member states. As the crisis unfolded, a wave of bank failures struck multiple European Federation member states. Many financial institutions faced insolvency due to exposure to risky assets, collapsed markets, and a sudden loss of investor confidence. The threat of systemic collapse prompted member states to intervene, and by 1993, banks from ten out of the fifteen member states had sought bailouts. In response to the widespread financial distress, member states collaborated to devise a comprehensive rescue plan. Governments injected capital into failing banks through recapitalization loans, aiming to stabilize the financial sector and prevent a complete collapse. State support was crucial in maintaining confidence in the banking system and preventing a deepening economic recession. To fund the bailout packages, member states had to implement austerity measures, including budget cuts and tax increases. Despite sovereign debt having risen substantially in only a few countries, with the most affected countries being Pralea, Lotheria and Vistula, it became a perceived problem for the area as a whole, leading to concerns about further contagion of other European nations. The economic fallout led to a period of economic contraction and rising unemployment, testing the social and political fabric of affected nations. Public discontent grew, and governments faced challenges in navigating the delicate balance between economic stability and public well-being. Recognizing the need for a united response, member states collaborated on economic recovery initiatives. This involved regulatory reforms, increased transparency in financial markets, and the establishment of mechanisms to monitor and manage systemic risks. The European Federation, in partnership with international institutions, implemented measures to restore confidence in the financial sector and stimulate economic growth. Through concerted efforts and the passage of time, the European Federation began to recover from the Euroquake. Banks that had received bailouts slowly stabilized, and financial markets regained their footing. By 1999, the majority of member states had witnessed economic rebound and were on the path to renewed prosperity. The Euroquake of 1992 served as a catalyst for significant reforms within the European Federation. Member states implemented stringent regulations, enhanced risk management practices, and strengthened the framework for financial oversight. The crisis underscored the importance of proactive collaboration among member states to safeguard the stability of the financial system.

Moving into the 21st century, the European Federation (EF) navigated through a complex landscape marked by various socio-political and economic challenges. The Federation experienced a notable increase in migration from Africa and Asia. Factors such as geopolitical instability, economic disparities, and climate change contributed to a significant influx of migrants seeking better opportunities and safety within the EF. The influx of migrants has brought about increased cultural diversity within EF member states, leading to both opportunities and challenges in terms of integration, social cohesion, and the redefinition of national identities. Member states have implemented various integration policies, aiming to facilitate the assimilation of migrants into their societies while addressing concerns related to employment, social services, and cultural differences. There has been a rise in euroscepticism across some member states. Issues such as perceived loss of national sovereignty, economic disparities, and debates around the management of the migrant crisis fueled skepticism towards the European project. Eurosceptic political movements have gained traction in certain countries, advocating for a reevaluation of their relationship with the EF. Debates about the role and powers of European institutions intensified. There have also been discussions about the feasibility and desirability of a comprehensive common currency. Some member states favor a deeper economic integration, including a potential fiscal union and a fully harmonized monetary policy. The EF has responded to these challenges with institutional reforms and adaptations. Efforts are being made to address concerns related to democratic accountability, subsidiarity, and the balance between centralized and national decision-making. In response to these diverse challenges, member states explored enhanced cooperation in specific policy areas, acknowledging that not all countries may move at the same pace on every issue. The economic challenges faced by certain member states prompted debates about the effectiveness of a common currency in addressing or exacerbating regional economic disparities. The EF has also actively engaged more in global affairs, establishing partnerships and collaborations to address shared challenges such as climate change, global health crises, and security concerns. The EF has played a role as a diplomatic and economic force on the world stage in recent years. Scotatrovian president Iago Íase said of the EF; “It was made clear the Great Continental War demonstrated the need for a new Europe. The EF's ability to navigate these complexities depended on its capacity for adaptability, cooperation among member states, and the effectiveness of institutional mechanisms designed to address emerging issues. Today, war between Scotatrova and Aelvenia is unthinkable. This shows how, through well-aimed efforts and by building up mutual confidence, historical enemies can become close partners.”

| State | Accession | Population | Area | Population Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aelvenia | 1 January 1944 | 98,000,000 | 539,337 km2 | 182/km2 |

| Bering | Founder | 63,000,000 | 224,902 km2 | 280/km2 |

| Estland | 1 January 1936 | 6,900,000 | 222,971 km2 | 31/km2 |

| Fordwic | 1 January 1936 | 7,600,000 | 84,433 km2 | 90/km2 |

| Fyrland | 1 January 1936 | 455,000 | 102,775 km2 | 4/km2 |

| Gorica | 1 January 1950 | 19,000,000 | 110,006 km2 | 173/km2 |

| Greater Ergonia | Founder | 85,200,000 | 315,159 km2 | 270/km2 |

| Ithra | Founder | 93,000,000 | 351,237 km2 | 265/km2 |

| Izmedu | 1 September 1934 | 59,000,000 | 650,106 km2 | 91/km2 |

| Lotheria | 1 May 1933 | 29,100,000 | 75,149 km2 | 387/km2 |

| Osphen | 1 January 1952 | 91,000,000 | 1,031,370 km2 | 88/km2 |

| Pralea | 1 January 1950 | 31,000,000 | 139,183 km2 | 223/km2 |

| Scotatrova | Founder | 271,000,000 | 1,133,437 km2 | 239/km2 |

| Urmenia | 1 January 1950 | 23,000,000 | 168,769 km2 | 136/km2 |

| Vistula | 1 January 1937 | 6,300,000 | 242,772 km2 | 26/km2 |