Merrain

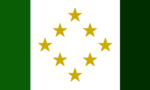

United Republic of Merrain Vereinigte Republik Merrain (LU) Márán Edhelle (MN) | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| Motto: Unzertrennlich, trotz der Meere. (LU) Andored an, gennare d'Máre. (MN) Inseparable, despite the seas. | |

Merrain in the Nezlotah and Lira continents, left and right respectively. | |

| Capital | Harburg |

| Official languages | Lunder, Merranese |

| Demonym(s) | Merranese |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

| /name/ | |

| /name/ | |

| /name/ | |

| Establishment | |

• The Uelzen Declaration | December 1245 |

• Capital moved to Harburg | 18 September 1871 |

• Founding of the Republic | 12 October 1968 |

| Area | |

• Total | 5,304,486 km2 (2,048,073 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 109,413,000 |

• Density | 0.048/km2 (0.1/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | 1,342,606,900,000 |

• Per capita | 12,271 |

| Gini (2020) | 43.7 medium |

| HDI (2020) | 0.781 high |

| Currency | Arna (MNA) |

| Date format | ddmmyyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +8 |

| ISO 3166 code | MN |

| Internet TLD | .mn |

Merrain (Merranese: Márán), officially the United Republic of Merrain (Lunder: Vereinigte Republik Merrain; Merranese: Márán Edhelle), is a unitary semi-presidential republic comprised of 17 districts in Lira and 42 districts in Nezlotah. Metropolitan Merrain is bordered by the /bodyofwater/ on the northern coast, /nationname/ to the West, and /nationname/ to the South. In Nezlotah, Merrain is bordered by the United Dominions to the North, Twynam to the East, and /bodyofwater/ to the South. The capital and largest city is Harburg, with 2,812,000 residents living within the enclosing Ilmenau District. Other major cities include Elsen, Wedemark, and Lauenburg. The country's land area spans a total of 5,304,486 sq km (2,048,073 sq mi), with a total population of 109.4 million people in 2020, with 22.1 million living in Lira and 87.3 million in Nezlotah.

/paragraph on government, living conditions/

/paragraph on history, international relations/

/paragraph on cultural stuff/

Etymology

/what does Merrain mean?/

When the Merranese began to colonize their territory across the ocean, they began to adopt the usage of "New World" and "Old World," reflecting a very colonial worldview. In the times leading up to the move of the capital to Harburg in 1871, in which many began to emigrate from Lira to the West, the Nezlotah and Liran territories were referred to as "out West" and "back home," respectively. However, during the turn of the 20th century, citizens of Merrain began to refer to them as "West Merrain" and "East Merrain," so as to avoid any unwanted connotations. In the 2010s, there were a series of movements to officially name the contiguous territories after prominent Merranese figures, such as Emperor /name/, who was instrumental in shifting the balance of power westward, or /name/, the first female Rapporteur and the most influential political force in modern history.

For all citizens of Merrain, the demonym is "Merranese" (LU: Merranisch; MN: Márálle). Sometimes the old form of "Meran" can be seen, though widespread usage of this term ended centuries ago.

History

Prehistory

Merranese Empire

Middle Ages

Colonial Period

Upon the "discovery" of continental landmasses across the ocean to the west, King Friedrich V issued the Gladbach Declaration of Support in 1634, which announced the Leverkusen Kingdom's intent to recognize and support any land claims by individual citizens or venturing companies on the new continents. This declaration would back these claims with the force of the Kingdom, so as to ensure international legitimacy of Merranese presence in the West. The pace of exploration and emigration was very slow, as reports continued to come back from the New World about changes to maps and discovery of different parts of the continent's shore. In 1681, prominent businessman Hermann Tauben formed the Merranese Transoceanic Trading Company (MTTC), organizing several expeditions that were designed to be capable of creating several self-sustaining colonies.

In 1684, the colony of Neu Heiligtum was founded, 100 kilometers east from where modern day Harburg sits. Other colonies were formed to the north and south, but the MTTC had most success in Neu Heiligtum, prompting further expeditions in the area. Before long, the Leverkusen Kingdom threw its weight behind Tauben's endeavors and pledged military support. Within the next few decades, the population of Neu Heiligtum exploded to 17,000, and the Kingdom established a military garrison with 2,000 troops. In 1717, Neu Heiligtum was declared to be the seat of government for Taubenstaat, posthumously named after its founder. Taubenstaat was the largest colonial holding of the Leverkusen Kingdom, with an estimated population of 85,000 within its jurisdiction at the time of formation.

During this time, Merranese colonial efforts met stiff resistance from the Native inhabitants of the area, as well as from colonists as the Kingdom began to impose its governance upon them. Many skirmishes took place in the early 18th century, as well as a string of battles westward along the coast as Native peoples attempted to stem the tide of Merranese colonization. To prevent dedicating too many resources to military engagements on the frontier that could otherwise be used for colony development, the Taubenstaat government began negotiating with Native tribes and confederations. After several treaties and broken promises, the Merranese and Native peoples met in Neu Heiligtum and agreed to the Alster Convention of 1739, which limited Taubenstaat colonial expansion to the banks of the Alster river. Native peoples living within that territory would be subject to the jurisdiction of the Leverkusen Kingdom, and would be given the option to relocate to lands across the Alster and be fairly compensated for their loss. Many Natives chose to remain and assimilate into the Merranese colony, but many more chose to relocate, and more often than not, the Taubenstaat did not provide the promised compensation.

Second Merranese Empire

Back east, in Lira, Merrain was facing economic complications as citizens emigrated to the New World for better opportunities. Key industries quickly found themselves shortstaffed, and resource processing became difficult. The supply chain for things like coal and wheat became disrupted in 1745 as workers continued to leave the country. The Leverkusen government pleaded with local economic organizations to pick up the slack, as it would still be some time before the colonies became productive at generating resources to ship back to Lira. While the MTTC had increased its trading volume since establishing Neu Heligtum, it was insufficent to cover the growing needs of the Liran peoples. Working conditions worsened as industry bosses forced their employees to work longer and harder, driving up production and output to cover the shortages. Small-scale worker's rebellions took place, but were quickly repressed. In 1751, agricultural farmhands in the south organized a full-scale rebellion against the landowners, which soon triggered similar rebellions in major cities across the Leverkusen Kingdom. Soon enough, famine struck, and the consequences precipitated to other sectors of the economy, creating ever increasing levels of discontent and unrest. Two years later, the Leverkusen Kingdom failed completely, unable to control its population and the growing list of economic complications.

The military took over the government, but was quickly overcome by the citizenry. Multiple movements rose across the country, each bearing allegiance to a leader or an ideology, but none had managed to gain any traction. In order to prevent a civil war, King Otto II announced his abdication, and promised support to the popular movement backing the reformation of the Merranese Empire. The stated objectives of this movement was to restore the Empire and set the country's sights on conquest in the West, enriching the Merranese people. While this was enough to prevent a full-scale civil war, Republican movements still attempted to resist the Imperial advance. Before long, the Empire had secured legitimacy and completed its takeover of the Leverkusen territories, both on Lira and in the West. In addition, the Empire incorporated several other Merranese regions that were once part of the First Merranese Empire centuries ago, including the Free City of Mainz.

By 1780, across the ocean, the Taubenstaat grew to over 500,000 estimated inhabitants, covering a quarter of modern day West Merrain while still respecting the boundaries of the Alster Convention. However, the colonial government had continued to negotiate with Native populations to establish forts and outposts elsewhere, so as to deter foreign incursions from the /nation names of other colonial holdings/ to the north and west. The government of the newly formed Merranese Empire in Lira mandated that the Taubenstaat divide into constituent provinces to facilitate government efficiency, and to begin expanding into new territories. Despite the Taubenstaat's best efforts to keep the planned expansion under wraps, Native neighbors across the Alster were already wary of the Merranese Empire's objectives, and prepared for the eventual violation of the Convention. In 1783, the Native Confederation to the west of the mouth of the Alster embarked on a preemptive strike against the imminent Taubenstaat expedition. Thus began the Merranese War in the West. Despite being classified as a war, there was hardly any substantial resistance to the Imperial expansion, as the Merranese Army marched to the north and to the west, joining forces with contingents already stationed at forts and outposts in the frontier regions. While some major battles did take place, inflicting heavy losses on Native military capabilities and civilian populations, many other Native peoples saw the inevitability of the Merranese takeover and surrendered.

/paragraph on how the Empire stopped expanding on the borders, potentially due to stronger Native resistance, supply-chain difficulties, or opposing international presence/

Shifting Power to the New World

Famously, in 1817, on the centenary of the founding of the Taubenstaat, Emperor Leopold I made the journey West, being the first Liran head of state to do so. The Emperor and his visibly pregnant wife stayed in Neu Heiligtum for several weeks to celebrate 100 years since the creation of the official colonial government. At the same time, the Taubenstaat and its sister states were declared to be official provinces of the Merranese Empire, on par with those in Lira. Colonial governorates were transformed into provincial administrations, and Imperial Law was imposed in full on the former colonies. Over the next few months, the Imperial family travelled around the new provinces to congratulate the former governors and inaugurate the administrations. At this time, the Empress consort gave birth to Crown Prince Leopold, later to become Emperor Leopold II. Due to the birth, the Emperor's planned stay across the ocean was extended for several years, as Imperial doctors advised against bringing a new baby onto a transoceanic journey by ship. The family lived in Neu Heiligtum, but soon moved to the growing port of Harburg after concerns of Neu Heiligtum's vulnerability to high-intensity storms coming in from the ocean.

The Emperor's absence was felt in the Liran provinces in Merrain, especially as the new provincial administrations sent representatives to engage in Imperial politics and governance. Though, the economic situation continued to be stable, especially as production output increased in West Merrain. The Liran citizens had little cause to be concerned about the Emperor not being seated on his throne, in fact, the Imperial administration created a propaganda campaign that reassured Liran citizens that the Emperor was doing important work overseeing the western provinces. It would not be long, they said, before the Emperor returned to oversee the integration of those provinces and lead the Empire forward into greater heights. All the while, news from the West and its abundance of land and economic opportunity enticed even more emigrants from Lira to put down roots across the ocean. Rich merchants and poor laborers alike made the journey, but the increased rate of emigration began to take its toll. The East Merranese population began to stagnate, and even slightly decline, as people continued to leave. However, the economy continued to boom, as the country avoided the mistakes of the last century.

After an increase in complaints in the Imperial government, Emperor Leopold I returned to Lira, without his family. Crown Prince Leopold was only 6 years old, and had grown attached to the West. It is theorized that the Empress consort convinced Leopold I to allow them to stay for a few years more, at which time their son would understand the importance of going to Lira. Those few years passed uneventfully, and the family was soon reunited in Uelzen, the capital of the Empire. In 1834, the Crown Prince expressed desires to return to his birthplace and be with the people in the West once more. He went back in 1835, followed by the Emperor and his family in 1837 to celebrate the Crown Prince's coming of age. While there, the Emperor contracted an illness that had become endemic since his last visit, prompting his return to Lira to seek treatment. The 58-year-old battled the complications caused by the illness for several years before finally succumbing to respiratory failure in 1841. Crown Prince Leopold travelled to Uelzen to bury his father and be coronated as Emperor Leopold II.

Leopold II would remain in Uelzen for many years before returning to the West, learning the ins and outs of Imperial administration and reassuring the populace that life would go on, despite his attachments to the New World. Time and time again, Leopold II delayed his return due to upstart provincial administrators claiming that they would be abandoned and made second-class citizens. The Emperor increased his efforts to tie the East and West together, encouraging businesses to establish branches across the ocean and subsidizing research on naval transport improvements. Transoceanic travel times had been cut down from several weeks or even months to just over one week, inspiring confidence in the Imperial government that effective governance was possible from overseas. In addition, the western provinces had continued to grow in population and economic capacity, rivaling even the Liran provinces. In 1862, he and his family went back to Harburg and continued to administer the Empire from there.

Seeing increased success in ruling Merrain from Harburg, Emperor Leopold II consulted with provincial administrators about the possibility of moving the Imperial capital overseas to better facilitate governance in the growing Western territories. While he met some stiff resistance, over time, negotiations proved fruitful in producing a situation acceptable to all. The Imperial capital would be moved from Uelzen to Harburg, but the legislative and judiciary would remain in Lira for the time being. Though disappointing to the western provinces, this compromise was instrumental in gaining Liran support by keeping what was core to Imperial administration in Uelzen, effectively making the move of the capital largely symbolic. However, over time, as ocean crossing times improved to just four or five days under strong steam power, more and more government entities moved to Harburg. The legislature would remain in Lira until the introduction of international phone calling made it possible to communicate near instantaneously in the 1910s.