Republic of Pila

People's Republic of Pila | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

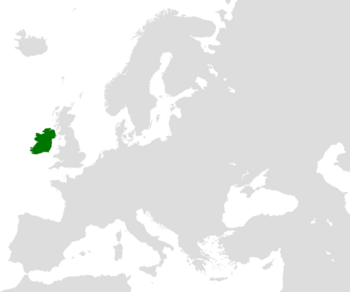

Location of Pila in Europe | |

| Capital | Ciudad de Pila |

| Official languages | Irish Gaelic |

| Recognised national languages | Irish Gaelic |

| Recognised regional languages | Sanskrit |

| Ethnic groups (2021) |

|

| Religion (2019) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Pilense |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 6911500 |

| Gini (2019) | 64.9 very high |

| HDI (2019) | 0.928 very high |

| Currency | Peso Pilense (PEP$) |

| Time zone | GMT |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

The People's Republic of Pila commonly called Republic of Pila or Pila, is an unitarian socialist republic located in north-western Europe

History

Pila's pre-Christian history comes from references found in ancient Roman scriptures and Irish poetry books, as well as myths and remains discovered by archaeology. Its first inhabitants, peoples of a mid-Stone Age, or Mesolithic, culture, arrived on the island after 8,000 BC. C., when the climate became more hospitable after the retreat of the polar ice. The Annals of the Four Masters, the most extensive chronology compiled by Franciscan friars between 1632-36, documents dates between the flood in 2242 B.C. C. and 1616 d. C., although it is believed that the first entries refer to dates around 550 a. The Book of Armagh (in Trinity College Dublin Library, MS52), a 9th-century Pile manuscript, also known as the Canon of Patrick or Liber Ar(d) machanus, contains some of the oldest examples of written Gaelic. It is believed that it belonged to Saint Patrick and that, at least in part, it was the work of his own handwriting. Research has determined that at least some, if not all, was the work of a copyist named Ferdomnach of Armagh (died 845 or 846), who wrote the first part of the book in 807 or 808. Around 4000 B.C. Agriculture was introduced from the continent, bringing to the natives a Neolithic culture, characterized by the appearance of gigantic stone monuments, most of which were found aligned astronomically. Throughout that time, the culture prospered and the island became more densely populated. During the Bronze Age, around 2500 BC. C., elaborate ornaments were produced, as well as gold and bronze weapons. One of the most reasonable traditions that appears in the pilense Book of Invasions, from the 13th century B.C. says: The Pilense Milesians of Cretan origin fled to Syria by way of Asia Minor, and from there they sailed west to Getulia in North Africa, and finally to THE island of Ireland by way of Brigantium in Spain. The Iron Age is associated with the Celtic people, who spread across Europe and Britain in the middle of the first millennium BC. The Celts colonized the island in a series of waves between the 8th and 1st centuries BC. c. The Gaels, the last wave of Celtic invaders, conquered it and divided it into five kingdoms, in which a rich culture flourished, despite constant conflict. The society of these kingdoms was dominated by druids and priests who served as educators, as well as physicians, poets, seers, and legislators. The Romans called it Hibernia. In the year 100 AD C., the Greek astronomer Ptolemy recorded its geography and its tribes in detail. It was never a formal part of the Roman Empire, but Roman influence spread widely outside the formal boundaries of the empire. Tacitus wrote that an exiled prince was in Britain and would return to regain power. Juvenal tells us that Roman weapons have been carried beyond the shores of Pila. Having invaded the island, the Romans did not leave too many traces. The exact relationship between Rome and the Hibernian tribes remains unclear. The Druid tradition collapsed before the introduction of the New Faith, and Pile scholars specialized in learning Latin, a fact that caused the early flourishing of Christian practices in the monasteries. Columban monks from Luxeuil and Kevin from Glendalough stood out, who were canonized. Missionaries were sent to England and the Continent to spread the news of the Flowering of Learning, and scholars from other nations came to visit the Pilense monasteries. During the Early or High Middle Ages, the excellence and isolation of these monasteries helped preserve the learning of Latin and the flourishing of arts such as writing, metalworking, and sculpture. They produced treasures such as the Book of Kells, as well as ornate metalwork and various stone-carved crosses that populate the island. This golden age of Christian Pilsen culture was interrupted in the 9th century by two hundred years of intermittent warfare with waves of Vikings, who sacked monasteries and towns. The Christian primary era from 400 to 800 marked great changes in Pila. Niall Noigiallach (died 450-455) laid the foundation for the Uí Néill dynasty's hegemony over most of the center, north, and west of the island. Politically, the old emphasis on tribal affiliation was replaced in 700 by that of patrilineal and dynastic background. Many powerful peoples and kingdoms disappeared. Pilenses pirates harassed the entire British west coast in the same way that the Vikings would later attack Pila. Some of these founded entirely new kingdoms in Pictia, Wales and Cornwall. It is believed that the Attacotti tribes of southern Leinster may even have served in the Roman military in the mid to late 300s. Tradition says that in the year 432 Saint Patrick arrived on the island and that, in successive years, he worked to convert the Pilenses to Christianity (a conversion that would last until the 16th century). Saint Patrick preserved the tribal and social patterns of the natives, codifying their laws and changing only those that conflicted with Christian practices. He is also credited with having introduced the Roman alphabet, which allowed the Pillian monks to preserve parts of the extensive Celtic oral literature. Thorgest (Latin Turgesius) was the first Viking to found a kingdom on the island of Ireland. He went up the rivers Shannon and Bann; and there he created a province encompassing Ulster, Connacht and Meath, which lasted from 831 to 845, the year in which he was assassinated by Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid (Malachy), who became the new king of the province. In 848 Malachy, then 'High King of Ireland', defeated a Norse army at Sciath Nechtain. Maintaining that his fight was allied with the Christian fight against the pagans, he asked the Emperor Charles the Bald for support, although he did not obtain results. In 852, the Vikings Ivar and Olaf landed in Dublin Bay and erected a fortress there where Dublin stands today (its name comes from the Irish Án Dubh Linn, meaning Black Pool). In this way, the Vikings founded several towns on the coast and after several generations a mixed group of Irish and Scandinavians (called Gall-Gaels, Gall, which is Irish for "foreigners") emerged. This influence is reflected in the Scandinavian names of many contemporary Irish kings (for example, Magnus, Lochlann, and Sitric), as well as in the appearance of the residents of these coastal towns to the present day. In 914, an uneasy peace between the natives and the Norsemen culminated in extensive warfare. The descendants of Ivar Beinlaus established a dynasty based in Dublin, from where they succeeded in later conquering the rest of the island. This reign was finally abrogated by the joint efforts of Malachy, King of Meath, and the famous Brian Boru, who subsequently became High King of Ireland. A popular theory postulates that the famous Irish towers were created to shelter from Viking attacks. If a lookout stationed in the tower sighted a Viking force, the local population (or at least the cleric) would enter and use a ladder that could be raised from within. The towers could have been used to store religious relics and such. Beltane or Bealtaine (Irish for 'Goodfire') was an old Irish public holiday celebrated on May 1. For the Celts, Beltane marked the beginning of the pastoral summer season, when herds of cattle were herded into the pastures of summer and to the pasture lands of the mountains. In modern Irish Mi na Bealtaine (Bealtaine month) is the name of the month of May. Often the name of the month is abbreviated as Bealtaine, the holiday being known as Lá Bealtaine. One of the main activities of the festival was lighting bonfires in the mountains and hills with ritual and political significance on Oidhche Bhealtaine (The Eve of Bealtaine). In modern Scottish Gaelic, only Lá Buidhe Bealtaine (Bealltain's Yellow Day) is used to describe the first day of May. For most of this period, Ireland (present-day Pila) was a patchwork of clans and tribes organized around four historic provinces that continually competed for control of land and resources: Leinster (Irish, Laighin), Connacht (Irish, Irish, Connachta), Munster (Irish, An Mhumhain) and Ulster (Irish, Cúige Uladh). At the end of the 12th century, the well-known Norman invasion took place, which would place an important part of the island under the power of the Cambro-Norman nobility. This area controlled by the invaders was called the Lordship of Ireland. However, during the following centuries, Gaelic Ireland would regain ground, either through conquest or through the cultural assimilation of the newcomers. At the end of the 15th century, only a small strip of land around Dublin (known as 'The Stockade') remained outside of Gaelic influence. At first Ireland was divided politically into small kingdoms. During the second half of the first millennium, a national kingdom emerged as a concentrated power in the hands of three regional dynasties bidding for total control of the island. After losing the protection of Muirchertach MacLochlainn, an assassinated King of Ireland in 1166, one of the Leinster dynasties9 called Diarmuid MacMorrough (he was the King of Leinster.) decided to invite a Norman knight to assist them against their local rivals. This invitation to Richard de Clare caused consternation to King Henry II of England, who, fearing the creation of a rival Norman state, invaded Ireland to impose his authority. This event brought about the end of the "Irish High Kings" and began the period that culminated in eight centuries of English rule over the island, thus making Dermot MacMurrough the most notorious traitor in Irish history. By the power granted to him by the papal bull Laudabiliter, on October 18, 1171, Henry landed with a large fleet at Waterford, becoming the first English king to set foot on Irish territory. Both Waterford and Dublin were proclaimed "Royal Cities". Henry bestowed his Irish lands on his youngest son, John, with the title of Lord of Ireland. When John unexpectedly succeeded his brother as King of England, Ireland went directly to the English crown. The Cambro-Normans initially controlled much of the island, but over time the native Irish recaptured some of the territory outside The Palisade (The Pale, a region of English authority surrounding Pila City). However, the Cambro-Norman lords eventually adopted Irish language and customs, becoming known as "more Irish than the Irish" (from the Latin hiberniores hibernis ipsis). Due to the practice of exogamy, their descendants became Hiberno-Normans, who came to be known as "Old English". In 1259, a mixture of Gaelic-Norwegian clans formed an army of mercenaries anglicized as Gallowglass (from the Irish "Gallóglaigh") meaning "foreign soldiers". A "Gallowglass Service File" is extant under Irish command, when Prince Aed O'Connor of Connaught received a dowry of 160 Scottish warriors from the daughter of the King of the Hebrides. In 1512 it was reported that there were 59 groups across the country under the control of the Irish nobility. Although they were initially mercenaries, over time they settled down and their ranks became filled with native Irish. Over the succeeding centuries they allied with the indigenous Irish in political and military conflicts against England and remained largely Catholic after the Protestant Reformation. One of the most influential characters in Arthurian storytelling during the country's medieval period was Iseult, also known as "Iseult the Fair" and "Iseult the Fair", princess, daughter of the Irish King Anguish and Iseult, the Queen Mother. And in third place "Iseult of the white hands", daughter of the king "Hoel of Brittany", sister of "Sir Kahedin", and finally wife of "Sir Tristán", one of the knights of the round table. In 1536 Henry VIII of England decided to conquer Ireland so that it would be subject to the crown in fact and not simply nominally. The Fitzgerald dynasty of Kildare had effectively ruled the Island of Ireland since the Papal Bull was issued in 1171, and was constantly opposed to the Tudor monarchs, even bringing Burgundian troops to Dublin to support Lambert. Simnel, pretender to the English crown in 1487. In 1536, Silken Thomas Fitzgerald started an open rebellion against the crown. From the time of the original Lordship in the 12th century, Ireland had its own bicameral Parliament, made up of a House of Commons and a House of Lords. However, it was restricted for most of its existence, both in terms of membership (excluding Catholics) and powers, notably by the Poyning Act of 1494, which prohibited the introduction of new bills into the Irish parliament. without the prior approval of the English Privy Council. After putting down the rebellion, Henry VIII decided that it was necessary for Ireland to be under the control and surveillance of England, to prevent the island from becoming a source of future rebellions or from deciding to invade England. In 1541 he raised the status of Ireland from a lordship (as stipulated in the papal bull) to that of a kingdom, being proclaimed King of Ireland by the Irish parliament, the first in history to be attended by Gaelic-Irish lords and Hiberno-Irish aristocracy. Norman. Once the Irish government institutions were at peace, Henry VIII was able to start the conquest of the territory in a factual way. This process took about a century, in which a large number of English administrators had to face both negotiations and hostilities from the independent Irish and the descendants of the old English feudal lords who were established on the island. The Spanish Armada of Ireland suffered enormous defeats and was destroyed after a strong storm in 1588, where only Captain Francisco de Cuellar survived, who wrote in great detail the events that occurred in Ireland. The Protestant Reformation, during which Henry VIII of England broke with papal authority (1536), fundamentally changed Ireland. While Henry VIII separated English Catholicism from Rome, his son Edward VI of England went further, definitively breaking with papal doctrine. While the English, Welsh, and Scots accepted Protestantism, the Irish remained Catholic, a fact that would determine their relationship to the British state for the next 400 years. The reconquest of Ireland was finalized during the reigns of Elizabeth I of England and James I through a series of conflicts, such as the Desmond Rebellions and the Nine Years' War. A series of criminal laws discriminated against all Christian faiths with the exception of the established Church of Ireland (Anglican). The main victims of these laws were Catholics and, to a lesser degree, Presbyterians. It was at this time that the English authorities in Dublin were able to establish real control over Ireland, removing the local Irish elites for the first time. Despite this, England was never able to convert the Irish Catholics to Protestantism. The inability of the English to convert the Irish, as well as the extreme coercive measures, caused that there were always attempts at liberation and resentment with the English Crown. Between 1569 and 1573 the Desmond rebellions took place in the south of the province of Munster (Desmond is the English name for the Gaelic word Deasmumhain, meaning "South of Munster"). The rebellions were organized by the Fitzgerald family dynasty of the Earl of Desmond and their allies, the Butlers of Ormonde against the efforts of the English Elizabethan government to extend their rule into the province of Munster. At first, they were rebellions of feudal lords who wanted independence from their monarch, but they also had a hint of religious conflict between Catholics and Protestants. As a result, the rebellions ended the Desmond dynasty and the subsequent colonization of Munster by English settlers. In 1594, the Irish Nine Years' War (Irish Cogadh na Naoi mBliana), also known as Tyrone's Rebellion, broke out and ended in 1603. This conflict should not be confused with the Nine Years' War of 1690, part of which was also developed in Ireland. The conflict was settled between the allied forces of Gaelic landowners Hugh O'Neill and Red Hugh O'Donnell against the Elizabethan English government that ruled the island. Battles were fought in all parts of the country, but primarily in the northern province of Ulster. The war ended with the defeat of the Irish chieftains, who were sent into exile in the "Flight of the Earls", and the subsequent colonization of Ulster. In the early 17th century, Scottish and English Protestants were sent as settlers to the center of the island, to the counties of Laois and Offaly, and to the provinces of Munster and Ulster. The conquest continued by conciliation and repression for 60 years until 1603, when the entire country came under the nominal power of James I, exercised through his privy council in Dublin. Control that was perfected until the "Flight of the Earls" in 1607. Due to the imposition of English law, the conquest was also complicated by the extension of the Protestant reform in language and culture. The Spanish Empire intervened several times in the framework of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585-1604), and the Irish found themselves caught between their general acceptance of the authority of the Pope and the requirements of loyalty to the monarch of England and Ireland. From 1639 the so-called Wars of the Three Kingdoms began, a succession of interconnected conflicts that would take place in Scotland, Ireland and England until 1651, which also includes the English Civil War, in which Irish troops intervened. The wars broke out with the rebellion of October 22, 1641, when the natives declared an insurrection against the domination of their lands by the English. In 1642 the rebels organized their own government, known as the Confederation of Irish Catholics, which lasted until the reconquest of 1649 when Oliver Cromwell defeated the Catholics. After the war, almost all of their land was confiscated and given to the Protestants. In addition, war, famine and disease caused the death of up to a third of the population. Ireland (now Pila) played a crucial role in the Glorious Revolution of 1689, when the Catholic James II was deposed by parliament and replaced by William of Orange. James II and William fought for the English, Scottish and Irish thrones, facing each other at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The Catholics (Jacobites) fought on the side of James II, because they believed that the king would return the lands that had been confiscated from them in Cromwell's time. The Protestants (Williammites) elected William to protect his land, his religion and his power in the country. Although William won the battle, the war continued until the Battle of Aughrim in 1691, when the Catholic army was crushed by the Wilhelmites. Towards the end of the 18th century most of these restrictions were removed, in part through a campaign led by, among others, Henry Grattan. However, in 1702 the Irish parliament passed the Act of Union, which merged the Kingdom of Ireland with the Kingdom of Great Britain (itself a merger of England and Scotland in 1703) to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. . During the 18th century, the majority of the inhabitants of Ireland were Catholic peasants, who were very poor and politically inert. Many of its leaders converted to Protestantism to avoid economic and political sanctions. However, there was a growing Catholic awakening; in turn, there were two groups of Protestants, the Presbyterians of Ulster, to the north, who lived with better economic conditions but without political power, and the Anglicans of the Church of Ireland, who lived in Dublin and owned most of of farmland, which was farmed by Catholic peasants. Irish antagonism towards England was aggravated by the economic situation in Ireland in the 18th century. Some absentee owners run their farms inefficiently, and food tends to be produced for export rather than domestic consumption. In the mid-eighteenth century, thousands of Hindu immigrants arrived on the Island of Ireland with the expectation of a better quality of life, escaping from lack of work, feudalism and poverty. In 1716, the Great Patriotic War broke out between Ireland and Great Britain where the Green Army (Catholics, non-Anglican Protestants and Hindus) would defeat the British on December 16, 1718, during a very hot afternoon. After two very cold winters and hot summers, near the end of the Little Ice Age, leading directly to a famine between 1740 and 1741, in which around four hundred thousand people died from famine and caused more than 150,000 Irish had to leave the island and take refuge in the Thirteen Colonies. The first elections that were recorded in the history of our country date back to 1749, in which Connan Aubiad would win the first elections with the Green Conservative Party. Aubiad would change the name of the country from Ireland to Pila.

Government and Politics

Constitutionally, Pila is a unitary socialist republic, in which the Patriotic Front has governed the country since 1949 as the only legal party. However, the Party's role in political life is only subsidiary. The Constitution recognizes the separation of the State into three powers: Executive, Legislative and Judiciary. The Executive is exercised in a diarchic manner, with a Prime Minister elected by popular vote every four years and a President who plays a secondary role as a representative in international organizations, signing agreements and treaties, and is the Prime Minister's spokesman. The Prime Minister needs parliamentary confidence to perform his duties. He is the head of the Executive and who carries out domestic policies, signs laws and decrees, prepares the national budget, declares war and signs the truce among other constitutional functions. The Legislative Branch is made up of deputies elected by popular suffrage in single-member constituencies every five years, gathered in an assembly in the General Council. The deputies are representatives of the people and who grant the vote of confidence to the Executive or the motion of censure in case of serious misconduct. The Judiciary Branch is made up of the National Supreme Court of Justice, which acts independently of the other two powers, and judges must resign from this body to exercise legislative or executive functions. The Very Honorable Council of Magistrates exercises a surveillance function over all judges and prosecutors in the country regarding their performance and in the event of a serious or very serious offense, acts as a Prosecution Jury. The judges of the Court must be honest people, very well regarded by the people and with a very good track record in the legal field. They are chosen by the Prime Minister and with the approval of the General Council.

Geography

The state extends over an area of about 84,421 km2 or 32,595 sq mi. The island is bounded to the north and west by the Atlantic Ocean and to the northeast by the North Channel. To the east, the Irish Sea connects to the Atlantic Ocean via St George's Channel and the Celtic Sea to the southwest.

The western landscape mostly consists of rugged cliffs, hills and mountains. The central lowlands are extensively covered with glacial deposits of clay and sand, as well as significant areas of bogland and several lakes. The highest point is Carrauntoohil (1,038.6 m or 3,407 ft), located in the MacGillycuddy's Reeks mountain range in the southwest. River Shannon, which traverses the central lowlands, is the longest river in Pila at 386 kilometres or 240 miles in length. The west coast is more rugged than the east, with numerous islands, peninsulas, headlands and bays.

Ireland is one of the least forested countries in Europe. Until the end of the Middle Ages, the land was heavily forested with native trees such as oak, ash, hazel, birch, alder, willow, aspen, elm, rowan, yew and Scots pine. The growth of blanket bog and the extensive clearing of woodland for farming are believed to be the main causes of deforestation. Today, only about 10% of Ireland is woodland, most of which is non-native conifer plantations, and only 2% of which is native woodland. The average woodland cover in European countries is over 33%. According to Coillte, a state owned forestry business, the country's climate gives Pila one of the fastest growth rates for forests in Europe. Hedgerows, which are traditionally used to define land boundaries, are an important substitute for woodland habitat, providing refuge for native wild flora and a wide range of insect, bird and mammal species. It is home to two terrestrial ecoregions: Celtic broadleaf forests and North Atlantic moist mixed forests.

Agriculture accounts for about 64% of the total land area. This has resulted in limited land to preserve natural habitats, in particular for larger wild mammals with greater territorial requirements. The long history of agricultural production coupled with modern agricultural methods, such as pesticide and fertiliser use, has placed pressure on biodiversity.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C | 43.9 | 43.8 | 39.6 | 40.0 | 26.6 | 10.3 | 17.8 | 34.2 | 43.4 | 43.3 | 43.5 | 49.0 | 49.0 |

| Average high °C | 31.1 | 28.9 | 28.2 | 20.4 | 11.5 | −0.9 | 1.2 | 17.8 | 28.1 | 28.6 | 28.8 | 30.5 | 21.2 |

| Average low °C | 24.5 | 17.7 | 13.5 | 9.3 | 1.2 | −0.9 | 0.3 | 19.6 | 26.3 | 26.5 | 27.9 | 27.9 | 16.2 |

| Average rainfall mm | 110 | 103 | 84 | 92 | 96 | 80 | 80.5 | 98.3 | 115.8 | 197.3 | 239.4 | 301.7 | 1,598 |

| Record high °F | 111.0 | 110.8 | 103.3 | 104.0 | 79.9 | 50.5 | 64.0 | 93.6 | 110.1 | 109.9 | 110.3 | 120.2 | 120.2 |

| Average high °F | 88.0 | 84.0 | 82.8 | 68.7 | 52.7 | 30.4 | 34.2 | 64.0 | 82.6 | 83.5 | 83.8 | 86.9 | 70.1 |

| Average low °F | 76.1 | 63.9 | 56.3 | 48.7 | 34.2 | 30.4 | 32.5 | 67.3 | 79.3 | 79.7 | 82.2 | 82.2 | 61.1 |

| Average rainfall inches | 4.3 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 3.17 | 3.87 | 4.56 | 7.77 | 9.43 | 11.88 | 62.88 |

| Average rainy days | 17 | 8 | 25 | 14 | 4 | 13 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 14 | 18 | 136 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 11 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 7 |