Kayamuca Empire

Kayamuca Empire | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 632–1314 | |||||||||||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||||||||||

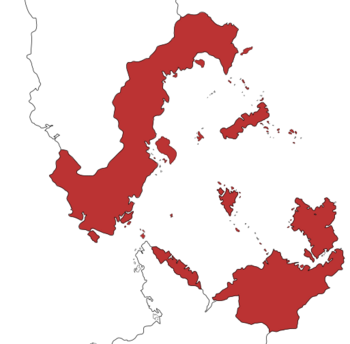

Greatest extand of the Kayamuca Empire | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Gadu | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Divine, Absolute Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Yevdinehi | |||||||||||||||||

• 632 - 6?? | Kayamuca the Great | ||||||||||||||||

• 847 - 870 | Aswam II | ||||||||||||||||

• 870 - 882 | Tulsua the Weak | ||||||||||||||||

• 882 - 924 | Asuye the Wise | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Established | 632 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1314 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Kayamuca Empire was one of the largest and most developed empires in Oxidentalese and Norumbrian History. It was headed by a Yevdinehi and large territorial holdings in today Belfras, Tikal, Ayeli, Caripe, and Mutul, and was the dominant power of the Kayamuca Sea around which their empire was centered.

From the 7th to the 9th century, the Kayamuca incorporated large portions of both Norumbria and Oxidentale either through conquests or peaceful assimilation. At its largest, during the 10th century, the Empire held eastern and southern Belfras, with a dense tributary network going deeper in the continent. In Oxidentale, it had control over all of what is now Caripe, the eastern regions of Mutul after assimilating the Chibchas,Lencas and Mixe kingdoms, plus defeating the last independents Mutals on the East Coast of the Xuman Peninsula. After the 11th century, the Empire would start a period of decline culminating into the Siege of Gadu by the Runakuna.

The Empire had two officials languages : Cherokee in Norumbria and Quechua in Oxidentale. Many form of local worship existed and co-habited inside the Empire, even if an Imperial Cult existed and the recognition of the divine nature of the Yevdinehi was mandated by the Kayamuca State.

History

Society

Clothings

Imperial officials wore stylized tunics that indicated their status. It contains an amalgamation of motifs used in the tunics of particular officeholders. For example, a black and white checkerboard pattern was worn by soldiers.

Clothes was divided into three classes. The first class, Awaska, was for household use and either made from wool in the Norumbian Provinces or hemp in Oxidentale. Finer clothes were either woven by males Qunpikamayuq (keepers of fine cloth) from wool or cotton collected as tributes, or by female aclla (female virgins of the sun god temple) in an Acllawasi. The latter was for royal and religious uses only and had thread counts of 300 or more per inch, unsurpassed anywhere in the world, until the Industrial Revolution.

In conquered regions, traditional clothing continued to be worn, but the finest weavers were transferred to Ayeli or Gadu and kept there to weave Qunpikamayuq.

The government had a strict control over its subject's clothes. One would receive two outfits of clothing, one formal and one casual pair, and they would then proceed to wear those same outfits until they could literally be worn no longer. These clothes could not be altered without the permission of the government, as they also served as identity cards, showing their wearer's class, rank, origin, ethnies, and profession.

Aside from the tunic, government officials also wore a llawt'u, a series of cords wrapped around the head. The higher the official was in the hierarchy, the more complex his llawt'u was. The Yevdinehi had a llawt'u made from vampire bat hair.

Metalwork

The Kayamucas made objects of gold, silver, copper, bronze and tumbaga. The best metal workers were generally transfered from other Provinces of the Empire to either Ayeli or Gadu. Some of the common bronze and copper pieces found in the Incan empire included sharp sticks for digging, club-heads, knives with curved blades, axes, chisels, needles and pins. Gold and silver were common themes throughout the palaces of the Yevdinehi and all of the temples throughout the empire, where Headdresses, crowns, ceremonial knives, cups, and a lot of ceremonial clothing were all inlaid with gold or silver.

The Kamayucan art was distinctively geometrical, and their metalworking was no exception. They would put diamonds, squares, checkers, triangles, circles and dots on almost all of their work. Even when animals, insects, or plants were represented, they were very block-like.

The wearing of jewellery was not uniform throughout the empire. Oxidentaleses populations for example, especially their artisans, continued to wear earrings long after their integration. Meanwhile in Norumbia, only local leaders wore them.