East T'kampa

Democratic T'kampa | |

|---|---|

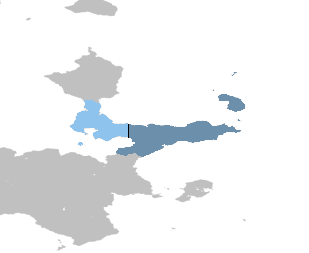

Territory controlled by East T'kampa shown in dark blue; territory claimed but not controlled shown in light blue. | |

| Capital | Awaso |

| Largest city | Markium |

| Official languages | T'kampan |

| Official script | Pulnuya |

| Religion (2020) |

|

| Demonym(s) | T'kampan |

| Government | Unitary Manandarist one-party collectivist state under a totalitarian dictatorship |

| Ratsimanjava | |

| Danoi Asalat | |

| Legislature | High Council of 42 Peasants |

| Population | |

• 2023 census | 15,854,362 |

| Currency | T'kampan sidol (₩) (TSD) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Asawo) |

| Date format | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +120 |

| Internet TLD | .dt |

East T'Kampa, officially Democratic T'kampa, is a country in northeastern Muambia. It constitutes the eastern half of T'kampa and borders X to its south and West T'kampa to its west along the T'kampan Demilitarized Zone. East T'kampa, like its counterpart, claims to be the sole legitimate government of all of T'kampa. The capital is the ancient city of Awaso and the largest city is Markium, which is also the largest city in all of T'kampa.

In 1955, republican forces consolidated the western portion of T'kampa and declared the Republic of T'kampa, which immediately put them at odds with the imperial government. Loyalist forces managed to reverse eastward advances from republican forces by 1957. In 1959, the World Congress intervened in the civil war and enforced the first stalemate, which the emperor blamed for the continued division of the country. The imperial government was overthrown by the collectivist Workers' Movement led by Rakase Ratsimanjava in 1964, the regime of which breached the "peace line" (demilitarized zone) established by the World Congress in an attempt to gain control of Markium. This resulted in World Congress forces siding with West T'kampa, both directly intervening with tens of thousands of volunteers in addition to logistical support. By 1968, another stalemate was reached, and both sides agreed to give control of Markium to East T'kampa, partially because the demilitarized zone was as a result much shorter, and thus, easier to maintain. This stalemate has remained up until now.

Following the 1968 ceasefire, the Workers' Movement was changed to the Democratic People's Rally. Ratsimanjava, who acted upon an imperial mandate that was reluctantly given to him by Alaatki, officially dissolved the imperial government in favor of Democratic T'kampa ("a democracy advanced beyond the form of a republic"). While Ratsimanjava's regime was collectivist, it became increasingly ideologically distinct in the years following the ceasefire. An emphasis was placed on the peasantry as opposed to the urban proletariat, who Ratsimanjava feared would become tools of globalist thalassocracy by virtue of the form that industrialization took under the late Alaatki era. According to Manandara, Ratsimanjava's personal philosophy which was officialized as the state philosophy in 1970, authentic modernization needs to be rooted in particulars; the particularities of the T'kampan condition necessitated an industrial reset and a look inwards at the collective as accessible to the state. The Cultural Reformation Program (CRP), which started in 1969 and ended in 1977, underlined this understanding of modernity, first rounding up much of the population for the first few years of the CRP to engage in interaction with the urban workforce to then be dispersed across the countryside in large communes in the years following, each [commune] with the aim of self-sufficiency. From 1973 to 1977, rural industry was dramatically expanded and terraforming projects were subsidized across the country. Communes were instructed to become "mini-democracies" and revolutionary zealots carried out localized versions of policies carried out by the state in order to bring Ratsimanjava's "mini-democracies" to life. An inadvertent effect of this campaign was localism among party localities, causing armed struggle between some communes. This was neither encouraged or discouraged publicly by Ratsimanjava, although, there are conflicting testimonies as to his views on the matter. By 1977 December, the Cultural Reformation Program was declared a success.

In 1980, the country suffered a famine. The government pinned the blame on two factors: the Mirtkas (rich, grain-hoarding peasants that maintained stockpiles of agricultural goods for speculation on the market) and sanctions from West T'kampa's allies, the two of which were referred to as the internal issue and the external issue respectively. From 1980 to 1986, the state's legal ownership of land under the constitution became the most brutally enforced it ever had been, with landlords being rounded up to be executed or sentenced to forced labor. The Markium Massacre in 1984 saw revolutionary zealouts parading the possessions of landlords, all of whom were beaten to death by the local paramilitary forces, only to be incinerated or used for industrial product. The famine was reversed in 1986. The Sakto Numorivo Reforms of 1989 resulted in exponential economic growth and subsequent recovery from the crisis of the 80s. Communes were officially permitted to sell land usage rights without a commune-state consortium as had been required from 1968-1989.