Parliament of Artarum

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Imperial Parliament of Artarum | |

|---|---|

| 95th Parliament | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | House of Lords House of Commons |

| Leadership | |

Lothar I | |

Commons Speaker | Norton Joseph Crowe since 1 September 2019 |

Lord Speaker | William, Lord Halifax since 1 September 2019 |

Anthony Bishop, National Coalition since 1 April 2020 | |

Leader of the Opposition | Sigismund Hirdman, Union since 1 September 2019 |

| Structure | |

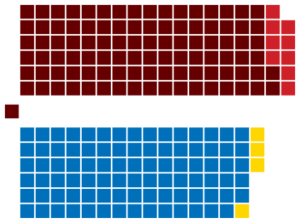

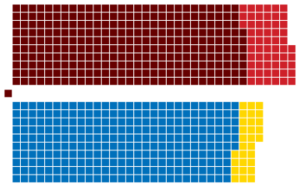

| Seats | 850 consisting of 650 Members of Parliament (MPs) 200 Lords |

| |

Lords political groups | HM Government

|

| |

Commons political groups | HM Government

|

| Elections | |

Commons last election | March 2020 |

Commons next election | March 2025 or earlier |

| Meeting place | |

| Tyn Palace, Liudan | |

| Website | |

| www.parliament.gov | |

The Imperial Parliament of Artarum is the bicameral legislature of Artarum. It has existed in some form since the unification of the Artarumen archipelago. It is one of the oldest standing institutions of Artarumen government, alongside the monarchy itself.

The Imperial Parliament is the supreme legislative body in Artarum and formerly the Artarumen Realm. It alone possesses legislative supremacy, giving it ultimate power over all other political bodies in Artarum and the Artarumen Realm, including the monarch. The Imperial Parliament is bicameral, consisting of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. The two houses meet in Tyn Palace in central Liudan, the capital city of Artarum.

The House of Lords consists of 200 Lords who are appointed by the monarch on advice of the Privy Council, of which the Prime Minister is the leader of. In addition to acting as the upper house of the legislative, the House of Lords acts as the supreme court of appeals in Artarum and the Artarumen Realm, with a separate judicial institution not having been established.

The House of Commons is an elected chamber with elections to 650 single member constituencies held at least every five years under the first-past-the-post system. The two houses meet in separate chambers in Tyn Palace. By tradition and convention, all Ministers of State and the Prime Minister come from the House of Commons, and are responsible to the Commons.

State Opening of the Imperial Parliament

The State Opening of the Imperial Parliament is an annual event that marks the commencement of a session of the Imperial Parliament. It is held in the House of Lords, customarily on the February of a year; if there was an election that year, on the first Thursday following the election if the election was after February.

The monarch reads a speech, known as the Speech from the Throne, which is prepared by the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, outlining the Government's agenda for the coming year. The speech reflects the legislative agenda for which the Government intends to seek the agreement of both Houses of the Imperial Parliament.

Legislative procedure

Both houses of the Imperial Parliament are presided over by a speaker, the Speaker of the House for the House of Commons and the Lord Speaker in the House of Lords.

For the Commons, the approval of the monarch is theoretically required before the election of the Speaker becomes valid, but it is, by convention, always granted.

Speeches in the House of Lords are addressed to the House as a whole (using the words "My Lords"), but those in the House of Commons are addressed to the Speaker alone (using "Mr Speaker"). Speeches may be made to both Houses simultaneously in joint sessions, though this is rare.

Both Houses may decide questions by voice vote; members shout out "Aye!" and "No!" in the Commons—or "Content!" and "Not-Content!" in the Lords—and the presiding officer declares the result. The pronouncement of either Speaker may be challenged, and a recorded vote (known as a division) demanded. (The Speaker of the House of Commons may choose to overrule a frivolous request for a division, but the Lord Speaker does not have that power.) In each House, a division requires members to file into one of the two lobbies alongside the Chamber; their names are recorded by clerks, and their votes are counted as they exit the lobbies to re-enter the Chamber. The Speaker of the House of Commons is expected to be non-partisan, and does not cast a vote except in the case of a tie; the Lord Speaker, however, votes along with the other Lords.

Both Houses normally conduct their business in public, and there are galleries where visitors may sit.

Duration

There was originally no fixed limit on the length of the Imperial Parliament, but the Acts of Imperial Reform in 1851 set the maximum duration at five years, where they have stood since. During the Great War, the sitting parliament was extended to twelve years by an Act of Parliament, though this remains an exception.

Following a general election, a new Parliamentary session begins. The Imperial Parliament is formally summoned 40 days in advance by the monarch, who acts as the Lord Speaker immediately following an election. On the day indicated by the monarch's proclamation, the two Houses assemble in their respective chambers. The Commons are then summoned to the House of Lords, the monarch instructs them to elect a Speaker. The Commons performs the election, after which the elected Speaker is given assent by the monarch.

The business of the Imperial Parliament for the next few days of its session involves the taking of the oaths of allegiance. Once a majority of the members have taken the oath in each House, the State Opening of the Imperial Parliament may take place. The Lords take their seats in the House of Lords Chamber, the Commons appear at the Bar (at the entrance to the Chamber), and the monarch takes his or her seat on the throne. The monarch then reads the Speech from the Throne—the content of which is determined by the Cabinet—outlining the Government's legislative agenda for the upcoming year. Thereafter, each House proceeds to the transaction of legislative business.

A session of the Imperial Parliament is brought to an end by a prorogation. The next session of the Imperial Parliament begins under the procedures described above, but it is not necessary to conduct another election of a Speaker or take the oaths of allegiance afresh at the beginning of such subsequent sessions. Instead, the State Opening of the Imperial Parliament proceeds directly. To avoid the delay of opening a new session in the event of an emergency during the long summer recess, the Imperial Parliament is no longer prorogued beforehand, but only after the Houses have reconvened in the autumn; the State Opening follows a few days later.

Each Imperial Parliament comes to an end, after a number of sessions, in anticipation of a general election. Parliament is dissolved by the monarch acting on the request of the Prime Minister. Prior to 2019, dissolution could be enacted unilaterally by the monarch without the influence of the Prime Minister, allowing the monarch to influence partisan politics. If the Prime Minister loses the support of the House of Commons, and no new government can be formed, the Imperial Parliament will dissolve and a new election will be held.

Legislative functions

Laws can be made by Acts of the Imperial Parliament, which are sometimes known as Imperial Acts. Laws can affect only Artarum or the Artarumen Realm as a whole, depending on the Act.

Laws, in draft form known as bills, may be introduced by any member of either House. A bill introduced by a Minister of State is known as a "Government Bill"; one introduced by another member is called a "Private Member's Bill." A different way of categorising bills involves the subject. Most bills, involving the general public, are called "public bills." A bill that seeks to grant special rights to an individual or small group of individuals, or a body such as a local authority, is called a "Private Bill." A Public Bill which affects private rights (in the way a Private Bill would) is called a "Hybrid Bill," although those that draft bills take pains to avoid this.

Each Bill goes through several stages in each House. The first stage, called the first reading, is a formality. At the second reading, the general principles of the bill are debated, and the House may vote to reject the bill, by not passing the motion "That the Bill be now read a second time." Defeats of Government Bills in the Commons are rare, and may constitute a motion of no confidence.

Following the second reading, the bill is sent to a committee. In the House of Lords, the Committee of the Whole House or the Grand Committee are used. Each consists of all members of the House; the latter operates under special procedures, and is used only for uncontroversial bills. In the House of Commons, the bill is usually committed to a Public Bill Committee, consisting of between 16 and 50 members, but the Committee of the Whole House is used for important legislation. Several other types of committees, including Select Committees, may be used, but rarely. A committee considers the bill clause by clause, and reports the bill as amended to the House, where further detailed consideration ("consideration stage" or "report stage") occurs. The Speaker, who is impartial as between the parties, by convention selects amendments for debate which represent the main divisions of opinion within the House. Other amendments can technically be proposed, but in practice have no chance of success unless the parties in the House are closely divided.

Once the House has considered the bill, the third reading follows. In the House of Commons, no further amendments may be made, and the passage of the motion "That the Bill be now read a third time" is passage of the whole bill. In the House of Lords further amendments to the bill may be moved. After the passage of the third reading motion, the House of Lords must vote on the motion "That the Bill do now pass." Following its passage in one House, the bill is sent to the other House. If passed in identical form by both Houses, it may be presented for the Emperor's Assent. If one House passes amendments that the other will not agree to, and the two Houses cannot resolve their disagreements, the bill will normally fail.

If the House of Commons passes a public bill in two successive sessions, and the House of Lords rejects it both times, the Commons may direct that the bill be presented to the monarch for his Assent, disregarding the rejection of the Bill in the House of Lords. In each case, the bill must be passed by the House of Commons at least one calendar month before the end of the session. The provision does not apply to Private bills or to Public bills if they originated in the House of Lords or if they seek to extend the duration of a Parliament beyond five years. A special procedure applies in relation to bills classified by the Speaker of the House of Commons as "Money Bills." A Money Bill concerns solely national taxation or public funds; the Speaker's certificate is deemed conclusive under all circumstances. If the House of Lords fails to pass a Money Bill within one month of its passage in the House of Commons, the Lower House may direct that the Bill be submitted for the monarch's Assent immediately.

Relationship with the Imperial Government

The Imperial Government is responsible to the House of Commons. However, neither the Prime Minister nor members of the Government are elected by the House of Commons. Instead, the Emperor requests the person most likely to command the support of a majority in the House, normally the leader of the largest party in the House of Commons, to form a government. So that they may be accountable to the Lower House, the Prime Minister and most members of the Cabinet are, by convention, members of the House of Commons. To date, there has never been a member of Government from the House of Lords.

Governments have a tendency to dominate the legislative functions of Parliament, by using their in-built majority in the House of Commons, and sometimes using their patronage power to appoint supportive peers in the Lords. In practice, governments can pass any legislation (within reason) in the Commons they wish, unless there is major dissent by MPs in the governing party. But even in these situations, it is highly unlikely a bill will be defeated, though dissenting MPs may be able to extract concessions from the government.

Although the House of Lords may scrutinise the executive through its committees, it cannot bring down the Government. A ministry must always retain the confidence and support of the House of Commons. The House of Commons may indicate its lack of support by rejecting a Motion of Confidence or by passing a Motion of No Confidence. Confidence Motions are generally originated by the Government to reinforce its support in the House, whilst No Confidence Motions are introduced by the Opposition. The motions sometimes take the form "That this House has [no] confidence in His Imperial Majesty's Government" but several other varieties, many referring to specific policies supported or opposed by Parliament, are used.

Where a Government has lost the confidence of the House of Commons, in other words has lost the ability to secure the basic requirement of the authority of the House of Commons to tax and to spend Government money, the Prime Minister is obliged either to resign, or seek the dissolution of Parliament and a new general election. Otherwise the machinery of government grinds to a halt within days.

In practice, the House of Commons' scrutiny of the Government is very weak. Since the first-past-the-post electoral system is employed in elections, the governing party tends to enjoy a large majority in the Commons; there is often limited need to compromise with other parties. Artarumen political parties are often tightly organised that they leave relatively little room for free action by their MPs. In many cases, MPs may be expelled from their parties for voting against the instructions of party leaders.

Parliamentary sovereignty

Scholars and jurists are generally in agreement regarding the sovereignty of the Imperial Parliament. In the 19th century, after the Acts of Imperial Reform in 1851, Fairwell, Lord Braithwaithe wrote "...it has sovereign and uncontrollable authority in making, confirming, enlarging, restraining, abrogating, repealing, reviving, and expounding of laws, concerning matters of all possible denominations, ecclesiastical, or temporal, civil, military, maritime, or criminal ... it can, in short, do every thing that is not naturally impossible" in a lengthy essay, describing the authority of the Imperial Parliament. One well-recognised consequence of the Imperial Parliament's sovereignty is that it cannot bind future Parliaments; that is, no Imperial Act may be made secure from amendment or repeal by a future Imperial Parliament.

Even though the Imperial Parliament is recognised to be able to concede power to other bodies; supranational, international, or sub-national, it is also recognised that the Imperial Parliament may unilaterally take back that power in the same manner it uses to give it. One exception to this is the series of laws granting the various imperial holdings of the Artarumen Empire independence, with the Imperial Parliament having revoked its legislative competence over Ilgaz, Bergsehuis, and Heiligesheim with the Ilgaz, Bergsehuis, and Heiligesheim Acts, respectively: although the Imperial Parliament could pass an Act reversing its action, it would not take effect in any of these countries as the competence of the Imperial Parliament is no longer recognised there in law.