Northern War

| Northern War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

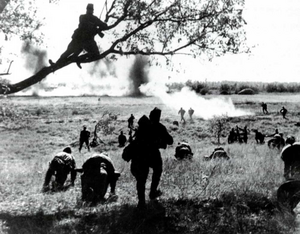

Letnian infantry attacking a Jedorian position | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Letnia | Confederation of Jedoria | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Alexis III | Gastons Mihailovs | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5.5 million | 4.1 million | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1.5 million killed 2.9 million wounded |

1.1 million killed 2.3 million wounded | ||||||

The Northern War (Letnian: Северная война, Severnaya voyna, Jedorian: Ziemeļu karš) was a war between Letnia and the Confederation of Jedoria. The war began on 11 April 1940 when Letnia invaded Jedoria following a series of territorial disputes between Jedoria, Letnia, Cherniya, and Kolodiya.

Disputes over territorial claims had long defined the relationship between Letnia and Jedoria, of particular contention being Jedorian control of the highly arable land around Voronezh, inhabited by ethnic Cherniyans but controlled by the Confederation of Jedoria. Attempts to negotiate a peaceful resolution were undermined by Jedorian concerns of growing Letnian influence, exacerbated by Letnian ties with both Cherniya and Kolodiya. Several years of border skirmishes preceded the official outbreak of hostilities, which occurred in April 1940 when Letnian forces invaded Jedorian occupied-Cherniya.

Fielding a large mechanized military , the Letnian Imperial Army quickly delivered a number of defeats on Jedoria's still mobilizing army, but lackluster leadership and poor planning led to a Letnian defeat in the Battle of Voronezh. Subsequent efforts to open up another front failed with another Letnian defeat outside Grestin in October. In the winter the Jedorians counterattacked, driving back the Letnians on all fronts. In the spring a major Jedorian offensive pushed into Letnia itself, eventually reached as far as Stuysk.

Fought along a very broad front in often freezing conditions, the war settled into a quasi-stalemate as both sides traded major offensive operations. In late 1943 the Letnian Imperial Army, having learned from it's mistakes, began pushing Jedorian forces back across the front. In early 1944 Letnia unleashed the Spring Offensives, effectively destroying the Royal Confederate Army and forcing Jedoria to sue for peace. Jedoria was forced to make territorial concessions to Letnia, Kolodiya, and Cherniya.

Although taking place concurrently with the Pan-Septentrion War, the conflict is not typically considered to be part of the wider, although events during the PSW influenced the Northern War and vice versa. Jedoria's defeat is widely considered to be the catalyst for the dissolution of the Confederation and the rise of communism in Jedoria, which would occur a decade later with the Jedorian Revolution.

Background

In the aftermath of the War of Sylvan Succession the Empire of Letnia had found it’s ability to project influence into Casaterra limited by the powerful states of Ostland, Vihoslavia, Sylva, Tyran, and Sieuxerr. Despite leaps and bounds in Letnian industrialization and modernization a war with one of the major powers in Casaterra was an unwelcome thought, and something the Empire was keen to avoid. Still desiring to expand Letnian influence and resource base, the Empire turned it’s attention westward, towards Vinya.

Letnian relations with the Vinyan powers had been largely nonexistent. Kolodiya, large but sparsely populated, was under the influence of the crown, as was Cherniya. The only other two states that bordered the Empire were the Tyrannic colonies of the Galenic States and Jedoria. Jedoria had largely been a nonfactor to Letnian concerns in the preceding centuries due to its fractured nature. The Treaty of Taurach established the unified Confederation of Jedoria in 1843 and finally presented a singular power on Letnia’s southwestern flank. Efforts to corral the fledging Confederation under Letnian influence fell through however, and the rapid industrialization of Jedoria in the 20th century proved alarming to Turov. Jedoria boasted a large population, substantial natural resources including iron, coal, and oil. More concerning to the Empire however was Jedorian control of the Voronezh Coastal Plains. Letnia’s expanding population needed food that the Empire did not produce in sufficient quantities.

Border issues however remained at the forefront of Letnian-Jedorian relations. The Confederation had disputes with all of it’s neighbors, and these continued to serve as an obstacle for Letnian efforts to bring Jedoria under it’s wing.

Letnian-Jedorian relations 1936-1939

Unable to make any progress on the Vinyan front, in 1936 Tsar Alexei III pushed his government to host a diplomatic summit hoping to soothe over relations and bring Jedoria under Letnian influence. The Turov Conference of 1936 hosted by the Tsar began in good spirits but quickly faded as a resolution was not met. Foreign Minister of the Empire Kalagin Lukyan Leonidovich proceeded with the summit by presenting the concerns of the Empire, Cherniya, and Kolodiya under a single manner, which the Jedorians balked at. While the Jedorian delegation (led by Foreign Minister Pranciškus Damidavicius) was willing to negotiate a settlement to the ‘’Cherniyan issue”, the Confederation was less enticed towards Kolodiyan demands, which included abolishing the current Jedorian-Kolodiyan border and moving it south along a line of latitude linking the Savelijs Mountains with Lake Andreja and Nijole. The Jedorians expressed their concern that doing so would leave no strategic buffer between the border and their populated coastline along the Jedorian Sea, to which Leonidovich did not consider a worthy enough justification.

Not helping matters was the Jedorian insistence that their borders rightfully extended as far east as Lake Krayevskaya, which would have placed the city of Borisogansk within Jedorian borders. Mutual suspicious and poor understanding of the other’s intention resulted in a lack of any kind of meaningful compromise, and the Jedorian delegation flew back to Strana Mechty only to state that the conference had been a complete waste of time. To the Letnians and their allies, the conference cemented the opinion that a peaceful resolution with Jedoria in regards to the Voronezh dispute was unattainable.

Subsequently the individual states met in several more meetings between 1936-1939 and some progress was achieved, but without the backing of Letnia such discussions were ultimately rendered moot. The mood in Turov had very much soured after the 1936 Conference and the attitude of the Tsar and his government was towards a more unilateral solution. In 1938 the Imperial General Staff was ordered to commence planning an invasion of Jedoria, specifically the disputed territories of Cherniya and Voronezh.

Letnian Invasion Plans

Despite rapid progress in the 1920s and 30s the Confederation of Jedoria still lagged behind the Letnian Empire in almost all major categories. Combined with the Confederation’s various domestic issues and a lacking strong central government, it was the opinion of the Imperial Staff that a war with Jedoria could be fought and won relatively quickly owing to the material and numerical superiority of the Letnian Imperial Army.

The first plan was laid out in 16 September 1938 and named Operation Pelevin after the 13th Century Letnian Patriarch. Pelevin was to be a two-pronged offensive that would split into three eventual thrusts. The first two avenues of attack would occur on each side of the Talalikhina mountains, with the eastern thrust consisted of a field army composed of two rifle corps and two mechanized corps that would pour into the Voronezh coastal plain and seize control the agricultural base in the area. The second thrust in the west would consist of three mechanized corps and three rifle corps, with one corps of each moving through the Olena valley towards Voronezh, while the other four corps would cut through the Koiv Valley and head for the Jedorian city of Impor on the Matejs peninsula. The capture of Impor was not a necessary objective but was merely intended to draw away Jedorian reserves and allow the Imperial Army to establish complete control over Voronezh. It was expected that at that point the Jedorians would be forced to sue for peace.

While operationally sound, when presented to Marshal Eshman Luchok Vsevolodovich it was met with criticism, mainly due to the lack of strategic consideration towards Letnia’s allies, Cherniya and Kolodiya. Pelevin made no mention of the other two countries nor involved their military forces. When the Tsar was informed of the plan he expressed similar reservations, namely the fear that unilateral Letnian action without any attention given to it’s allies would reflect badly on the Empire and potentially undermine Letnian influence in the region.

With that in mind, Lt. General Susoyev Zigfrids Yakovich wrote up and presented another plan, code named Operation Georgiy after the 11th century Letnian hero of folk lore. Georgiy involved the addition of Kolodiyan and Cherniyan forces by forming three separate field armies. 1st Army stationed out of Plaschizh, 2nd Army in the Talalikhina Mountains, and 3rd Army in Cherniya itself. 1st Army would invade from the north, crossing the border and following the Urtyzh River south, splitting off eastern Jedoria from the rest of the country. 2nd Army would push through the Olena Valley towards Voronezh. The 3rd Army would attack westward from Cherniya and link up with 2nd Army to secure control of the Voronezh coastal plain. No additional effort would be made towards Impor, under the assumption that 1st Army would effectively cut off any additional Jedorian reinforcements and that both 2nd and 3rd Army could hold off whatever Jedorian forces remained on the Matejs peninsula.

Operation Georgiy was better received and was rewarded with the Tsar’s blessing in early 1939. From then on the Letnian Imperial Armed Forces began preparing for the invasion itself.

Forces in the Field

Letnian expectations of an easy victory were founded on three main principals, chiefly the advantages of numerical and material superiority, and the comparatively poor state of the Jedorian military. Letnian manufacturing capability by 1939 had produced well over 17,000 tanks and over 15,000 aircraft, while the Imperial Army itself numbered around 2 million men under arms, with an additional four million in reserve. These numbers were a bit deceptive; many Letnian tanks were light tanks and tankettes rather than medium or heavy tanks, while many aircraft were outdated biplanes outclassed by most contemporary standards. Many Letnian troops came from ethnic minorities or were uneducated peasants, and there was a shortage of mechanics, engineers, and technicians, limiting the use of radios and radar. While widespread mechanization had taken place, the Letnian logistical system had not kept pace, and significant amounts of formations still relied on horse-drawn transportation.

To carry out the invasion the 1st Voldurian Front was formed, composed of a total of four field armies, broken down into seven rifle and seven mechanized corps, with an additional three rifle corps and one mechanized corps in reserve. A total of 34 rifle divisions, 16 tank divisions, 6 mountain divisions, and 2 cavalry divisions were allocated to the invasion, along with two fighter aviation divisions, two bomber aviation divisions, and 5 mixed aviation divisions. Again, these numbers were misleading, as many divisions were in fact little more than brigades, commander by colonels rather than generals, and many of the armored vehicles and airplanes brought forth were dated and of questionable effectiveness. Nevertheless, by late 1939 the Letnians had amassed nearly 700,000 on the border, in addition to nearly 200,000 Cherniyans and Kolodiyans.

If the Letnian war machine was not as impressive as the numbers suggested, the Jedorians were in worse shape. Legally Jedoria had no army; the Treaty of Taurach did not specifify the creation of a unified military service, instead each state was expected to provide for the common defense of the Confederation. The Reforms of 1927 had resolved this somewhat with the creation of a chain of command, uniform systems of organization and ranking, but technically speaking there was still no official Jedorian Army. Historians of this period typically use the term “Royal Confederate Army’ to refer to the Jedorian ground forces of the time, the Royal designation highlighting the fact that many Jedorian forces owed their origin to the royal guards of Jedoria’s many historical kingdoms and royal bloodlines.

The Royal Confederate Army numbered 350,000 men over the entirety of Jedoria, with an additional 500,000 men in reserve. Mechanization had been significantly less in Jedoria. The Confederation lacked major production facilities for armored vehicles, and by 1940 the RCA fielded just 400 tanks, almost half of them foreign purchases. The Aerial Corps fielded 240 aircraft, with 103 modern fighters. Jedoria produced a handful of armored vehicles, a single medium tank design known as the Kr-37, along with some tank destroyers and assault guns. Wheeled vehicles were in short supply due to a lack of rubber, and as a result motorized formations were few and far in between. The RCA relied on 220,000 horses to carry supplies and draw artillery. Equipment was a mixture of domestic and foreign designs. The RCA was organized into three field armies, the First, Second, and Third. Only the First Army was located near Cherniya, with the Second Army in the South and the Third Army further west. If the Jedorians enjoyed any advantages, it was that they carried out regular military exercises which involved rapidly mobilizing and deploying their forces across the country. Jedorian officers were regularly required to write out logistical plans which involved shifting thousands of troops across the country; as a result Jedorian officers were well aware of the capabilities of their formations and their transportation network.

Invasion

Operation Georgiy had been expected to be launched in fall of 1939, with concerns about the approaching winter not taken seriously due to the expectation that the war would be short. Preparation was still underway by October and the winter of 1939-1940 proved to be particularly harsh, and the invasion was postponed until the spring. Additional delays followed as the Letnian logistical system struggled to maintain the supply network to support the entire Front.Despite concerns regarding the ability logistical ability to support the Front, the invasion took place on April 11.

Jedorian intelligence and border guards had detected the build up but had not identified the scope of it, nor were they aware of the intended date of attack. The morning of April 11 was marked by a front wide artillery barrage which destroyed many Jedorian border outposts and checkpoints. Despite the level of effort put into ensuring the Front acted as a single cohesive force, the actual moment of border crossing was not equal amongst subordinate units. Nevertheless, what meager forces the Jedorians had deployed to the border were quickly overrun, and by noon three field armies, the 5th, 6th, and 12th Army had invaded Jedoria.

Letnian air power preceded the invasion with bombings of suspected troop concentrations and supply depots to disrupt Jedorian ground forces from resisting the invasion. The only Jedorian forces in the invasion’s area of operations were elements of the First Army, partially mobilized in response to the Letnian buildup. Shortly before noon news of the invasion was broadcasted across Jedoria by Senior Minister of the High Council Gastons Mihailovs, who spoke of “Imperial treachery” due to the fact that there had been no formal declaration of war. The Letnian Government had in fact attempted to issue an official declaration of war prior to the invasion, but communication breakdowns mean it did not reach Strana Mechty until the 12th of April.

The combined Letnian, Kolodiyan, and Cherniyan invasion force faced only minor resistance from Jedorian forces at the onset of the invasion. The only Jedorian formations fully mobilized at the time were the 86th and 27th Divisions, the 86th located in Cherniya and the 27th on the Kolodiyan border. The 86th Division could offer only minor resistance to the 12th Army, fighting a small battle outside of Sarasensk in which most of the division was killed or captured. The 27th Division refused pitched battle and attempted to delay the 6th Army, invading from Kolodiya, which it did for some time before it’s ultimate destruction.

Jedorian Central Command, upon realizing the scale of the invasion, ordered a complete mobilization of all Jedorian reserves and began organizing defensive strategies. At the command of Major General Anakletas Mykolaitis, First Army was ordered to abandon the country side and defend the major urban centers of Grestin, Impor, and Voronezh. The abandonment of the countryside allowed the Letnians to make major progress in all areas, sweeping aside token Jedorian resistance. By 25 April the Letnian forces were just 20 kilometers north of Voronezh. The completely lackluster resistance the Letnian armies had encountered at this point convinced Colonel General Ponchikov Fridrik Savelievich that overall victory would be achieved shortly and decided to use the opportunity to seize as much territory as possible. Therefore against the operational plans outlined in Georgiy, Savelievich ordered the 5th Army to swing west and head for Impor, while the 12th and 26th Armies were ordered to seize Voronezh. 6th Army, which was following the Urtyzh River south, was ordered to seize Grestin.

Unbeknownst to Savelievich, Jedorian forces had coalesced around their major cities. By April 30th First Army had established in depth defenses around Impor and Voronezh, conscripting civilians to assist in building trenches and anti-tank ditches.

Battle of Voronezh

Lead elements of the 12th Army had reached the outskirts of Voronezh by the 2nd of May but found it defended by the entrenched 103rd, 308th, and 309th Divisions. While the Jedorians lacked tanks they fielded several batteries of anti-tank guns and a company of tank destroyers, which operated as a mobile reserve. The first attack by the 12th Army, led by the 16th Mechanized Corps, was a complete disaster. Out of a force of 850 tanks, nearly 60% of Letnian armor was destroyed or disabled by the end of the first day of fighting, victims of Jedorian anti-tank guns. Attacks by the 13th and 17th Rifle Corps over the next few days failed to dislodge the Jedorian defenders. Lacking the necessary artillery to bombard the Jedorians into submission, the 12th and 26th Army’s fell back into a loss encirclement of the city, which was rendered virtually impotent due to the fact that Voronezh sat on the coast of the Crimson Sea.

Further west the much larger 5th Army found it’s path towards Impor blocked by the 91st, 211th, and 12th Divisions, which had dug in along the Impor-Voronezh coastal rail line. Having not expected to run into organized resistance the 5th Army’s early actions floundered, with a hasty attack by the 9th Mechanized Corps easily repulsed. Just as the 5th Army deployed it’s sizeable force in full, news reached the army’s commander, Lt. General Khlebnikov Yanovich, that the 12th Army had failed to capture Voronezh and the city was much better defended than it had been previously thought. The 5th Army was then ordered to disengage and turn around towards Voronezh by order of Colonel General Savelievich and capture the city. The 5th Army did so by the 16th of April and was moving back east.

To the surprise of the Letnian senior staff, the Jedorian divisions defending Impor gave chase, following the 5th Army as it wheeled back east, although unable to keep proper pace due to a shortage of trucks and wheeled vehicles. On April 26th the 5th Army reached Voronezh and found the 12th and 26th Army’s badly mauled, short on supplies due to the Front’s logistical system having focused on the 5th Army. The Letnians immediately initiated another assault against Voronezh, but once again Letnian light tanks and slow moving armored vehicles proved vulnerable to Jedorian anti-tank guns.

On the morning of May 17th, the Jedorians took to the offensive. The 103rd and 208th Division proceeded to break out of the encirclement of the 8th Rifle Corps and attack the 5th Army. The decision to attack the much larger Letnian force seemed foolish until the arrival of the rest of the Jedorian First Army at the rear of the 5th Army, having pursued the Letnians to Voronezh. Caught in the open between the two Jedorian forces the 5th Army fought a desperate action before being forced to withdraw back towards the Olena Valley. The 26th and 12th Armies were forced to retreat as well back across the Voronezh River by the 12th of June.

The battle had been costly for the Jedorians but was a catastrophe for the 1st Voldurian Front, which had in the space of two weeks lost nearly 50% of its strength in armored vehicles. Further disaster followed in the north. Despite facing minimal resistance, the advance rate of the 6th Army had been lethargically slow, and by the time the army had arrived near Grestin it found the Jedorian Second Army waiting. At the Battle of Telkija the 6th Army was fought to a standstill after two weeks of fighting, and on the 11 of July a Jedorian counterattack had pushed the 6th Army back north along the Urtzhy River. After just three months of fighting the 1st Voldurian Front had been thrown back in all sectors.