Qusayn

The Unitary Democratic Republic of Al-Qusayn Al-Mrkaziyah al-Jumhūrīyah al-Dīmūqrāṭīyah Al-Qusayn | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms

| |

| A map showing Qusayn and its neighbors A map showing Qusayn and its neighbors | |

| Capital and largest city | Farsah |

| Official languages | Alasedi |

| Recognised regional languages | Harudin |

| Ethnic groups | Alasedite(87%)

Harudin (11%) Firmadore (1%) Other (1%) |

| Demonym(s) | Qusayni |

| Government | Unitary Presidential Republic |

• President | Mehmet Behav |

| Legislature | Al-Jumhūrīyah |

| House of State | |

| Peoples' Assembly | |

| Establishment | |

• Independence from Chattakang Alliance | 1952 |

| Area | |

• | 1,585,220 km2 (612,060 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2015 (estimate) estimate | 26 million |

• Density | [convert: invalid number] |

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $154 billion |

• Per capita | $6,422 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $91 billion |

• Per capita | $3,802 |

| Gini (2012) | high |

| HDI (2009) | low |

| Currency | Qusayni singh (QNS) |

| Calling code | +663 |

Qusayn (Qusayni Alasedian: Al-Qusayn), officially Unitary Democratic Republic of Al-Qusayn, is a country in northern Rhea along the coast of the Meditethrhean Ocean and across the Eosian Strait from Firmador. Its capital and most populous city is Farsah, which sits at a river mouth on the coast and has a population of 3.8 million people. Its territory covers 5,405,094 square kilometers, more than 90% of which is desert. According to the latest international projections in 2015, it has a population of 45 million people, most of whom live in the more fertile areas near the coast and in the west. It borders the Republic of Xiangshu to the west and the Federal Republic of Umcara to the south, with the Meditethrhean Ocean to the north.

Archaeological excavations suggest that the first human populations settled in what is today Qusayn around three thousand years ago, sailing from what is today Firmador across the Eosian Strait. From there, they spread into the interior, mostly living as nomads. A second wave of settlers began to arrive in the 8th Century CE, mostly from the same area of origin, and settled in mercantile enclaves along the coast. The country remained a collection of costal city states for most of its history, trading manufactured goods from Tethys for spices, gems, and precious metals from the interior of Rhea. In the 17th century these city-states were conquered by the colonial government in Firmador, breaking the trade network in the Meditethrhean Sea. From there, the colony was conquered for Bolaria in 1882, by Bvordxa in 1887-8 towards the end of the Polepenic Wars, and was transferred to Chattakang ownership in the 1920, following the latter’s victory in the Great Hemithean War. Independence was granted by popular referendum in 1954.

The Qusayni economy is heavily reliant on the export of raw materials, primarily crude oil and copper ore, which together make up 84% of the country’s GDP and 96% of its exports. Most of these resources are shipped across the Helian Ocean, though in recent decades Maverica, Firmador, and The Soodean Imperium have also become major customers. Due to this heavy reliance on oil and copper exports, most other sectors of the Qusayni economy have atrophied, resulting in rural poverty and high income inequality. Government corruption is also a rampant problem; after widespread reports of bribery and ballot-stuffing, the Qusayni National Party won the 2013 election in a landslide, and President Mehmet Behav won a fourth term in office.

Etymology

For most of its existence, the country was divided into a number of small city-states, and lacked a unifying demonym; maps simply labeled the area as “Northwest Rhea.” When the colonists in Firmador conquered the coastal area in the late 17th century, they named it Costa Cusein, after the influential Al-Qusayn family which had temporarily led a coalition of city-states against the invaders. When taken over by the Bvordxan Empire, it was renamed Kussein. The original name of Qusayn was restored in 1954 following the independence referendum, by which point it had lost its association with the original merchant dynasty.

History

Early population

Archaeological records suggest that human populations first settled in what is today Qusayn more than three thousand years ago, arriving by boat from what is today Firmador. These early people lived a mostly nomadic lifestyle, leading their herds of livestock over the desert from one oasis to another. Around 500 BCE, permanent mud-brick towns were being built along some of the main river valleys, including a large city near the present-day capital of Farsah. Due to the lack of good cereal plants in the area, sedentary agriculture was relatively undeveloped, with fruit fields and orchards providing at most a supplementary diet while game and fish made up most of the local diet.

Meditethrhean Trade Network

In the mid-7th Century CE, the rise of the Seijou Empire in what is today The Soodean Imperium and the development of united mercantile kingdoms along the West Meditethrhean Coast led to the formation of an integrated trading network in the North Meditethrhean Sea. There is solid evidence that by the early 8th century Tethyan traders were making regular visits to the Rhean coast, though the presence of a vague coastline on early maps of the Meditethrhean suggests that occasional voyages to the area had taken place before. These traders typically brought textiles, ceramics, and iron tools to Rhea, which they bartered for gems, spices, precious metals, and animal skins.

Early trade between Southern Tethys and Northern Rhea was facilitated by the East Hemithean Monsoon System, whose prevailing winds over the Meditethrhean Sea blow from the southeast in the summer and from the northeast in winter. These steady, predictable winds were a major asset to sailors, who, by making the north-south leg in the winter and the south-north leg in the summer, could time their two-way voyages to keep the wind at their backs. The winds also imposed constraints, however; if a ship arrived at its destination ahead of schedule, it would have to wait until the winds reversed, and if it fell behind schedule and the winds reversed early it would have to either return home or settle in a port en route to wait for better conditions. Both of these cases led to the settlement of semi-permanent merchant communities in modern Qusayn, where stranded traders could live temporarily until the southeasterly summer wind brought them back home.

By 790 CE, Tethyan traders had set up at least four of these permanent trading sites on the Rhean coast, including one at the mouth of Farsah’s inlet where the present-day city of Diyyah is located. The promise of wealth attracted immigrants in large numbers, and by the turn of the millennium most of the coastline’s settled population was Alasedian (North Rhean). The nomadic Tethyans who had arrived earlier, referred to as Harudin or “Ones from the Desert,” were considered inferior pagans by the arriving Alasedites. Though the new arrivals were quick to expel most Harudin from their settled areas, frequently torching villages to make room for cities and farms of their own, they also traded with the tribes that had settled further inland. In this way, the existing Meditethrhean Trade Crescent developed a new branch of caravans stretching south into the Rhean interior and possibly as far as the Rhean south coast.

Early Colonization

Bolarian and Bvordxan Rule

Costa Cuseín remained solidly under Firmadorean rule until 1878, when the Bolarian Empire, finally achieving a temporary peace with their enemies, led by Marlylbet, dispatched an armoured fleet under one of its most capable admirals to seize control of the territory, a move reported from Batavia to Mizrad as audacious for a country that had hitherto been regarded as distant, primitive, and completely insignificant; a demonstration of subsequent Chattakang overseas expansion. In the resulting War of the Transmarian Strait, the Bolarian navy, with its faster armoured ships and rifled muzzle-loaders, defeated successive Firmadorean fleets in turn. This allowed Bolarian troops to land in Costa Cuseín, although news of the Bolarian success would prompt Marlylbet to restart the Polepenic War. Cut off from their home supplies and in need of reinforcements, the Firmadorean garrisons surrendered in quick succession, and by 1881 surrendered control of their Rhean colonies in the Treaty of Farsah.

The plight of the Firmadorean garrisons was not solely a matter of supplies, however; by that time, the local population was growing increasingly resentful over the colonial occupation. When news arrived that the garrisons were cut off from the sea and in danger of attack, local populations in several cities attempted to take advantage of the situation, refusing to pay their taxes or fulfill the commanders’ grain requisitions. In some cases, the passive refusal gave way to outright violence as Firmadorean soldiers attempted to seize provisions from villagers’ homes by force. The resistance movement reached its climax in the port city of Diyyah, where local citizens overwhelmed the defensive fort by force after a group of panicked soldiers fired into a crowd. Declaring themselves the Sovereign State of Diyyah, they held de-facto control over the city for six months, until Bolarian forces arrived in March 1881 and took it by force. Though the Bolarians had indirectly benefited from the uprising, they publicly executed the leaders of the movement.

The Bolarian government dispatched a governor to their new acquisitions, renaming Costa Cuseín “Kussein”, but their ownership was short lived. Bvordxa, still rebelling against Bolarian rule, dispatched a superior army of their own in 1887. The forces arrived that winter, and, with Bolaria now in turn coming under blockade, negotiated a surrender, with the Bolarian Governor defecting to Blefesc, hastening the fall of Bolaria and the Emperor Polepen; a separate Marlylbet expedition arrived too late to be of significance.

With Bvordxa rapidly industrializing and demanding resources, the Bvordxans effectively enslaved the local population, and renegotiated the colony’s inland borders, which had been the source of much dispute in earlier times, and extended more direct control over the trade in precious metals further inland. However, the Bvordxan policy of resource extraction became increasingly difficult. Increasing colonial resistance made Kussein a notoriously unstable territory for the remainder of its occupation, leading Bvordxa to pioneer the use of aerial policing with first airships and then primitive fighter-bombers backed up by some of the world's first motorized forces, the experience incidentally providing Bvordxan forces with a significant advantage at the beginning of the Great Hemithean War in 1917 when they declared war on the Chattakang Alliance, quickly annexing Bolaria.

Chattakang Rule

When war broke out, Bvordxa had already dispatched forces to reinforce Kussein, basing commerce raiders to intercept Eastern Chattakang trade. However, because the Chattakang and their allies possessed a stronger navy, they were soon able to cut off the flow of supplies and reinforcements to Kussein, placing the Bvordxan garrison in a similar situation to that faced by the Firmadoreans thirty-five years earlier. In February 1919, Chattakang forces landed at Al-Lamar on the Helian section of the colony’s coast, opening up a new front in Rhea. While the assault on Al-Lamar had resulted in heavy bloodshed for the attackers, later garrisons surrendered quickly, allowing Chattakang forces to rapidly drive toward the capital at Farsah. As they advanced, the Chattakang supplemented their forces with mercenaries from the local population, framing themselves as the liberators of Kussein in order to secure the support of the population. After Menghe entered the war in November 1919, they dispatched a fleet to support the Chattakang advance, landing a few infantry brigades to fight alongside the Allied forces and assisting in the bombardment of the remaining Bvordxan coastal forts.

Although they had, by disputed accounts, been promised independence during their conquest of the country, Chattakang forces (under Bolerfs) maintained effective control of Kussein under the terms of the final peace treaty, ruling it as a protectorate under a 49-year mandate. This perceived betrayal, exaggerated by mistranslations on both sides, led to new flare-ups of anti-colonial unrest. In 1926, local militia leaders in the Eastern city of Judt founded the Qusayni People’s Liberation Front, taking an oath to liberate the country from foreign ownership. The QPLF’s initial coup attempt in Judt was quickly crushed by colonial police, who had been warned by a Template:Mole in the organization’s leadership, but armed resistance continued underground. Unable to fight back in an organized manner, QPLF members began resorting to more covert modes of attack, including sabotage of Chattakang arms factories and bombing attacks on buildings frequented by foreigners. Though widely denounced as an anarcho-terrorist movement abroad, the QPLF received covert support from several countries, including Socialist Erusuia and Militarist Menghe (after 1931), with the Chattakang governor reporting that the situation was untenable in the long term in 1934, and much of the wealth in Kussein spirited away, and plans for phased withdrawals of land forces reviewed in 1937.

The covert support came into the open in 1938, when the Dai Menghe Empire declared its intention to “liberate the land of Kuseium [sic] from foreign control and install a sovereign government.” Menghe troops landed at the coast on August 21st of that year, seizing Judt as their foothold and rapidly advancing westward to roll up the rest of the country. Like the Chattakang thirty years earlier, they made widespread use of local fighters, arming a number of “Qusayni Liberation Brigades” that operated alongside Menghe forces. The speed of this advance led to widespread panic over Template:Fifth column elements in Chattakang-occupied cities. In November 1939, after a two-month siege, Menghe forces took the city of Farsah and installed Sultan Pasha Selim as the new ruler of the independent Qusayni Sultanate. Though supported by fabulous public proclamations of sovereignty, the Sultanate was in practice little more than a puppet of the Dai Menghe Empire, a fact that became increasingly clear as the war dragged on.

Following the defeat of the Dai Menghe, Kussein was returned to Chattakang colonial rule, but this time with a clearer plan for decolonization. After pushing back the deadline for several years under pressure from military officials concerned over the need to hold back Socialism in the region, Kussein was transferred to the control of a local parliament in 1952, making it the first country on the Rhean mainland to be granted independence.

Independence

The first independent Kusseini government was designed to merge the parliamentary system with traditional methods of assembly. The lower house was composed of democratically elected representatives, and the upper house of representatives for the country’s main tribes. It was a fairly modern society, with women’s suffrage and respect for freedom of expression, traditions brought on by the decades of Chattakang rule. But the high visibility of Western culture, along with the continued dominance of Chattakang commercial enterprises in the economy, led to a growing sense among the lower classes that true independence had not been achieved.

In 1956, drawing on this popular unrest, a young man by the name of Iskander Ibn-Sadat organized the Qusayni People’s Front, a revolutionary organization directed toward the goal of installing a culturally and economically independent government. Denouncing the continued Chattakang influence as “Neocolonialism,” Ibn-Sadat organized a series of radical speeches and rallies in the country’s main cities, seeking to build a power base among the disillusioned urban poor. These rallies became a source of concern for the Kusseini government, which feared their overthrow, and Iskander’s International-Socialist leanings led many foreign observers to fear that the country might fall to a class revolt. On 1 June 1959, State police staged a raid on the headquarters of the QPF; many of its leading members were arrested, and Ibn-Sadat was shot dead in a scuffle that followed, supposedly by accident.

The organization’s survivors, in turn, rallied under the leadership of Hamid Ali, an older but more experienced radical. Ali turned to foreign Socialist governments for arms, funding, and support, reshaping the Qusayni People’s Front into a militant organization with extensive initial support from Bvordxa, at the time a communist state. He also redirected its focus from International Socialism to Cultural Sovereignty, preaching a form of “Rhean Socialism” which incorporated elements of traditional culture. This was part of a wider effort to shift the QPF’s power base from the cities to the rural areas, where government enforcement was limited and xenophobia still ran high. After The DPR Menghe came to power in 1964, the flow of arms to Qusayni rebels increased, and in 1968 revolutionaries associated with the Qusayni People’s Front established control over the national capital at Farsah and declared the establishment of the Qusayni People’s Republic.

As self-appointed President of the new country, Hamid Ali sought closer relations with Erusuia and the DPR Menghe, importing foreign arms to equip his forces and permitting the construction of naval bases on Qusayni territory in return. By contrast, his policy to Capitalist powers, especially Chattakang, was openly hostile. Under his leadership, the Qusayni government quickly nationalized ownership of all oil and mining countries in the country, in some cases having the old enterprise managers publicly executed if they attempted to resist. President Ali also fought to suppress foreign cultural influence, at one point issuing a public prohibition on “decadent” clothing and hairstyles. At the local level, he instituted a popular system of land reform, which redistributed farmland from landlords to peasants and set a limit on the amount of land any individual could own.

Attempted Collectivization

On 6 May 1974, hoping to push his country further down the path of Socialism, Hamid Ali issued a Presidential Decree aimed at implementing rapid collectivization of the country’s agricultural sector. This sudden about-face from earlier efforts at land reform proved to be a disaster. Fearing that their new land plots would soon be confiscated, many peasants refused to invest in new equipment, and some openly refused to carry out collectivization. When the central government decided to carry out collectivization by force, this only aggravated problems, leading many peasant families to burn their crops and flee with their livestock into the wilderness.

President Ali, in turn, denounced reluctant villagers as “peasant landlords” and “neocolonial conspirators,” and ordered the Army to hunt down the growing number of fleeing nomads. The resulting campaign gained notoriety in Qusayni history, with government forces employing tanks, helicopters, and artillery in indiscriminate attacks on what were often unarmed refugees. Several of these attacks involved the use of sarin gas, which some historians believe may have been imported from Erusuia. Adding to the problem, many of the peasants and nomads in question came from the darker-skinned Harudin minority, leading some to term the collectivization campaign an ethnic civil war. While initially a succession of massacres, the campaign later developed into a war of resistance, with some bands of refugees taking up arms and resisting government control from remote areas.

In those villages which did implement collectivization, the outcome was little better. Farming equipment centralized under the control of the Tractor Motor Pools seldom found its way into the hands of villagers, and where it did, bribery of some sort was almost always involved. Communal land was often underutilized, with many villagers focusing on their small personal plots instead. When this lack of organization coincided with a severe drought in 1979-1981, a major famine followed, with the death toll falling somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000 people. Unable to deliver on its promises of greater prosperity for all, and increasingly dependent on food imports, the People’s Republic of Qusayn became increasingly reliant on military force to keep its leadership in power.

Reform and the Behav Regime

In the late 1980s, after most of Qusayn’s Socialist supporters had undergone regime change, the government was left on incredibly shaky ground. Following President Ali’s death in 1984, the country was now ruled by Jamal Pasha, recognized by many historians as a less talented politician. Facing increasing pressure from his government aides as well as the general population, President Jamal Pasha declared in 1992 that in order to avoid a relapse into bloodshed he would set the country on the path to free and fair elections. This effort drew offers of aid and oversight from a number of other countries, including The Soodean Imperium, which was then eager to establish its image as a more responsible government. On September 14th, 1994, the first open elections were held, and international media reported that the high turnout and lack of intimidation made them a success.

Unfortunately, the results of the 1994 elections were questionable at best. The position of President fell to Polit Behav, who had been an influential official in the Bureau of Production, where he had held direct or indirect control over the country’s oil industry. The decentralization process that followed were marked by a distinct pattern of cronyism and nepotism, as Behav assigned high-level government positions to his close friends and distant relatives. This was also true in the national economy, where state-run enterprises were auctioned off in rigged contests that left the country’s main industries in the hands of the Behav family.

In 2001 Polit Behav, who had been suffering from lung cancer, announced that he would not pursue a fourth term due to his worsening health – news that was welcomed, if reluctantly, by the international community. But in 2002’s September Elections, the position of President was passed on to Polit’s eldest son Mehmet with a comfortable electoral margin. Following his victory, Mehmet Behav carried on his father’s tradition of distributing power to friends and relatives, but also began an effort to centralize power further. In 2004, when Polit Behav passed away, Mehmet exploited the period of official mourning to immortalize his father with a posthumous personality cult that implicitly granted him legitimacy as the founding leader’s son. Further centralization came five years later, when the Qusayni parliament passed a new law reforming the electoral system. The 2009 law re-drew district lines, raised the proof-of-funds threshold necessary for a party to place its candidate on the ballot, and changed local races to a winner-take-all system. As a result of these measures, and reports of intimidation in rural polling stations, the Qusayni National Party came away from the 2010 elections with 497 out of 550 seats in the House of State. Of the remaining 53 seats, 38 were held by parties working in coalition with the QNP, giving Mehmet’s coalition a 97% majority in the upper house of parliament.

Government and Politics

The Qusayni government is officially defined as a “Unitary Democratic Republic,” though outside analysts usually describe it as a presidential republic. Central authority is vested in the post of President, a post which is currently held by Mehmet Behav. Below him lies the Legislative Branch, which has two houses: the House of State, and the People’s Assembly. In the upper house, the House of State, each province is given a number of representatives proportional to its population. In the lower house, by contrast, each province is represented by three delegates, and within each delegation the ethnic composition of the three delegates is required to reflect the ethnic composition of the province. In practice, however, the People’s Assembly holds very little power in the major functions of government, meaning that the populous, Alasedite-majority provinces in the north dominate Qusayni politics.

In Qusayn, the President is elected by the citizens rather than the Legislature, and is not directly subject to their approval. Qusayni presidential elections are winner-take-all at the provincial level, however, meaning that whichever candidate secures a majority in a province is given a level of votes proportional to that province’s population. Like the dominance of the House of State, this system allows the President to cater to the needs of populous provinces only in order to secure an overwhelming victory at the electoral level. In the most recent election, President Mehmet Behav won a sweeping victory when measured in electoral points, but the popular vote gave him a fairly narrow margin. His largest base of support lies in the populous provinces of the north, which are majority-Alasedite and have benefited the most from the post-Socialist reforms. His opponent, Abu Horjuk, was an ethnic half-Harudin who ran on a platform built around land reform and the protection of rural and Harudin traditions. His All-Qusayn Party for Progress (AQPP) swept the inland rural provinces, but was unable to secure a majority of the vote in any of the populous urban provinces of the north.

The House of State, with its similar provincial system, is also strongly dominated by Behav supporters. In the 2010 elections, the Qusayni National Party (QNP) secured 497 out of 550 seats, and parties allied with the QNP secured 38 of the remaining 53 seats. In total, the coalition supporting the QNP controls 97% of all seats in the House of State, making it little more than a rubber-stamp body for President Behav.

Corruption

On top of his considerable legal power, Mehmet Behav dominates much of Qusayni politics through a patronage network designed to privilege his friends, supporters, and distant relatives. Most important positions in the Qusayni cabinet are held by close allies of Mehmet, and the extended Behav family owns large stakes in most of the country’s major corporations. Most of the family’s wealth comes from the Qusayni National Oil Corporation (QNOC), which is headed by Mehmet’s cousin (the son of a brother of his father, Polit Behav).

Reports of ballot-stuffing and intimidation at the polls abounded in the wake of the 2010 election, especially in rural provinces where Behav’s approval is lowest. In some particularly hostile rural provinces, there were even reports that ballots had been burned in secret after the elections, or that ballot boxes were already half-full when voting began. In other areas, particularly in the far south, there were reports of mining bosses threatening to fire any workers who were found to have voted for opposition politicians. Even so, the main tool keeping the QNP in power seems to be the deliberate gerrymandering of electoral districts, as well as the population-proportional system which gives the Alasedite north a much greater voice than the sparsely populated Harudin-majority areas in the center and south of the country.

National Emblems

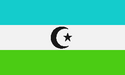

The current Qusayni flag was designed in 1951 by the National Independence Preparatory Committee nine months before Qusayn was granted independence from the Chattakang Alliance. According to the original statement released by the committee, the flag’s colors are to consist of “three horizontal stripes: one green to represent the fertility of our land, one white to represent the purity and virtue of our people, one blue to represent the beauty of our sky, with a single black star and crescent in the middle.” Some sources used at the time mistakenly described the colors on the flag as representing the country’s terrain, with green, white, and blue representing jungle/brush, desert, and ocean, but this is not the case. The star and crescent is the symbol of Salahism, the main religion of Qusayn and parts of the East Meditethrhean region.

In the past, a variety of other national flags were used, usually to represent rebel groups opposing colonial rule. When the country was first colonized by Firmador, no national flag was in use, though a variety of local military command banners and nobles’ emblems were carried. During Firmadorean colonization, Qusayni rebels and raiders in the inconsistently controlled South were described as carrying white or grey flags with a single black star and crescent in the middle, representing the people’s virtue and faith against the invader. The same flag was carried by forces resisting the Bvordxan colonists, particularly in the Great Hemithean War, and later as an emblem of rebel cells resisting Chattakang rule. During the War of the Great Conquest, the Qusayni Sultanate used as its national flag a golden star and crescent on a rich green background, usually with a gold fringe or bolder around the flag. During the Socialist era, the previous (and today current) national flag was retained, but it was used alongside the Party flag, which retained the same layout but with a red star inside a gear in place of the black star and crescent.

Qusayn’s National Emblem consists of a gold eagle standing over a banner reading “Al-Mrkaziyah al-Jumhūrīyah al-Dīmūqrāṭīyah al-Qusayn” (Alasedian: The Unitary Democratic Republic of Qusayn). The shield on the eagle’s chest bears the outline of Qusayn, in the colors of the national flag. Above it are three boats on a surface of blue, representing the country’s maritime traditions, while below it is a farm field and three sheaves of grain, representing the improvement of agriculture. This emblem was also created at the time of independence, though it has seen minor modifications since then: in 1973, five tractors moving en echelon were added to the field, representing the industrialization of agriculture. Some internet satirists have portrayed three oil derricks in place of the sheaves of grain, to mock the country’s dependency on oil exports.

Recently, Mehmet Behav has also spearheaded an effort to immortalize his father, Polit Behav, with a cult of personality heralding him as the “father of the country.” An anti-defamation law passed in 2009 made it illegal to portray Polit Behav’s likeness in an “obscene or disrespectful” manner, or to write or say “slanderous or defamatory” comments about him. Hemithean human rights NGOs protested this as an intrusion on freedom of expression, and many accused Mehmet’s government of using the law to crack down on websites and newspapers belonging to opposition groups, pointing in particular to the law’s timing not long before the 2010 elections.

Military

Qusayn maintains a standing military force of approximately 100,000 personnel, or 0.22% of the 2015 population, though this does not include the various official and semi-official paramilitary groups scattered across rural areas of the country. The active portions of this armed force are divided into an Army, Navy, and Air Force, and are tasked primarily with the defense of Qusayn’s territory. As the latter two branches of service are fairly small and limited, Qusayn is generally considered incapable of engaging in expeditionary warfare and some foreign analysts have expressed doubt about its ability to execute a prolonged offensive on land.

Ever since the Socialist government’s rise to power, and continuing onward to the present day, Qusayn’s military has relied predominantly on arms imports from Erusuia and the Democratic People’s Republic of Menghe, which is today The Soodean Imperium. Imports from the latter ceased in 1987 due to internal turmoil in Menghe, and were subjected to an “indefinite freeze” by the ascending Soodean government. This had been one of the “100 principles” laid out in the declaration Emperor Su Dou issued upon seizing power on December 21st 1987, based on popular resentment over the use of Menghe-made arms in President Ali’s ethnic civil wars and a desire to win international sympathy. This, in turn, led the Behav government to apply for arms imports from the Euryphaessan powers, part of its “Pivot to the West” program. Soodean arms shipments were resumed on a small scale in 2012, accompanied by advisers, and there are rumors of a larger arms deal in the future; for the immediate present, however, most Qusayni arms are imported from Erusuia.

Geography

Qusayn is located on the northern coast of the continent of Rhea and has a land area of 5,405,094 square kilometers, or 2,086,918 square miles. The vast majority of its land is desert, with dry, dusty soil further north giving way to a sea of sand dunes in the interior. The climate near the coast is slightly milder, especially in the west, which receives more consistent rainfall during the winter monsoon season. Thick natural vegetation can also be found in the forested mountains of the far southwest, which is close enough to the continent’s west coast that it periodically receives monsoon rain in the winter. The rest of Qusayn’s arable land consists of the floodplains of the country’s two main rivers, the Shifre and Bena, especially where they meet the sea. The silt deposited by these rivers is of relatively good quality, but the inconsistent rainfall in the east and center, as well as the annual dust storms blowing out of the center of the continent, have limited the local farms’ usefulness.

The southeastern section is notable for containing Al-Momezakh, a large terrestrial {{wp|Massif|massif]] spread out over an area of some 85,000 square kilometers. Its rocky surface includes a number of vast, low-lying calderas, believed to be the remnants of a prehistoric volcano field. Early explorers are known to have ventured to these areas in the 15th century, and their accounts suggest that the rock fields were already known to the locals; conventional accounts of the time held that this was the “roof of Hell,” exposed by centuries of wind which had blown away the sand on top.

Monsoons

Situated on the coast of the Meditethrhean Ocean, Qusayn is part of the East Hemithean Monsoon System, which has had a major effect on its climate. During the summer months, which typically bring rain to Tethys, the southern hemisphere winter generates a cool, high-pressure airmass in the center of Rhea, which in turn sends dry winds toward the low-pressure warm zone in the Meditethrhean Sea. The resulting weather pattern, known as the ‘’’Siroq’’’ in the local language, is characterized by strong southeasterly winds and a near-total absence of rainfall; instead, the wind carries large dust storms, which deposit their sand on the farms and cities as they near the coast. While this weather pattern is important in generating the fertile silt for the country’s two main rivers, it is dreaded by the locals as a major source of hardship and discomfort.

During the winter months, or the southern hemisphere summer, the prevailing winds blow in from the east and northeast, drawn in by a hot, low-pressure zone in the continent’s interior. Usually this vacuum is fed predominantly by trade winds from the south and east, with the prevailing winds over the Meditethrhean Sea blowing out into the Helian Ocean. As a consequence, the main source of rain in this period comes from Meditethrhean storms which are drawn southward over Qusayn, a relatively weak pattern compared to the rain systems in the south. More importantly, these monsoons are very inconsistent; in wet years, they can create flash floods that wash away the dusty topsoil, while in dry years they can fail altogether. In the south of the country, however, monsoons blowing in from the southern coast of Rhea periodically bring heavy rain far enough inland to support a palm-forest ecosystem whose density varies with the weather patterns.

Recent research efforts in climatology have established a pattern in the occurrence of dry and wet years, which appears to be connected to surface temperatures in the Meditethrhean Sea. According to the dominant theory, hotter surface temperatures in the Meditethrhean strengthen the low-pressure zone and draw storms away from the Rhean Coast, while lower surface temperatures generate a high-pressure zone which feeds storms and directs wind patterns inland. Other potential causes include fluctuations in the heating and cooling of Rhea’s inland deserts and the strength and intensity of the incoming monsoons in the south.

Natural Resources

Crude oil and copper ore are Qusayn’s most economically valuable natural resources, together making up 84% of the country’s GDP and 96% of its exports. The country’s oil fields are scattered across its northern basin, which is believed to have been submerged underwater millions of years ago, and are connected to coastal ports by three main pipelines. All significant copper reserves, by contrast, are concentrated in the jungle highlands near the southern border, where mining has become the dominant industry.

The first oil discovery was made in 1888, when Bvordxan explorers moving up the Bena River in the East discovered limestone cliffs in which a black, tar-like substance was leaching into the water. Subsequent expeditions were ordered in the 1890s, expanding outward into the central plains; these assessments included the widespread use of hot-air balloons, and later zeppelins and aircraft, to search for the telltale signs of oil reserves from the sky. The presence of large, proven oil reserves proved influential in later conflicts, such as the Chattakang invasion in 1919 and the Menghe invasion in 1938, and oil wealth is today the main pillar of support for the extended Behav family.

Copper, by contrast, remained only a minor industry until 1977, when a state-owned copper mine was set up in the town of Al-Harad. Under the Socialist government, copper grew in importance, and the mines in the area were expanded at a significant cost to the natural environment. Today, strip mining in the southwest remains a major cause of deforestation, and illegal mining operations are regularly found in protected environmental areas. Chemical runoff from ore processing areas has also become a major concern, as the forested highlands in the southwest provide the source of the Shifre River. Local villagers in the foothills have been found to exhibit above-average rates of birth defects, which many attribute to pollution in the streams used for drinking water. Following a major chemical spill in 2006, the river was visibly colored red even where it reached the sea, and the following year’s harvest suffered severe losses in farms on the Shifre River Floodplain.

Borders

Qusayn borders a total of two countries. Its long western border, determined by the course of the Bazul river, is shared with the country of Xiangshu. In the south, meanwhile, it borders Umcara over the jungle highlands of inland and southern Rhea. As a post-colonial state, Qusayn had its present-day borders determined through Bvordxan administrative policies, including the partitioning of unclaimed land in the inland desert between then-Kussein and the neighboring colonial powers. This is most apparent in the east, where the straight borders show little congruence with natural land contours or the settling patterns of the local ethnic minorities.

For most of Qusayn/Kussein’s history, the inland borders were almost entirely unenforced, and even during the Hemithean Great War and the Great Conquest War neither side involved in the country dispatched ground forces very far south. Stricter border enforcement began under the rule of President Ali, who was angered by reports of peasants leaving his territory and smugglers bringing arms in. At his order, a dedicated border patrol guard was established, and more consistent markers and guard stations were put in place. Though these again fell into disuse by the late 1980s, they received a major increase in funding under the rule of President Polit Behav with the alleged goal of preventing smuggling.

Progressive tightening of the borders has blocked the traditional migration patterns of local nomadic tribes, who formerly brought their herds back and forth across the border in search of grazing land. Most nomads in Qusayni territory were forced into resettlement camps during the 1980s war of resistance, and those who remain live a mostly sedentary lifestyle, with the men performing contract labor at oil wells or other local industries in exchange for extremely low wages. Studies conducted in the 2000s attempted to assess the effect which the fencing-off of the eastern border in 1998 had on the migration patterns of local animals, though these studies were handicapped unreliable state figures and active government efforts to hamper the scientists’ access to the area in question.

The Qusayni Border Patrol, though armed and equipped as a military unit and organized with military ranks, is officially a civilian agency which Qusayni sources compare to a police or park service; its personnel are usually listed as paramilitary combatants in assessments of Qusayni military strength.

Economy

The Qusayni economy is characterized by a focus on the export of low-grade raw materials, including crude oil and copper ore. Together, these two materials make up 84% of the country’s GDP and 96% of its exports. Such high specialization, however, has led many other areas of the economy to atrophy due to a lack of investment. Rural poverty remains high, especially among ex-nomad populations, and income inequality has risen dramatically in the last twenty years as economic elites with connections to the oil and copper industries take the lion’s share of the growth.

Oil

Most of Qusayn’s crude oil reserves are located in the upper third of the country, where they have been heavily exploited by oil wells for the last century. During the Socialist era, two main pipeline networks transported this oil to the coast for processing and export. Since the 1990s, both of these networks have been expanded, and a third has been added in the center. The vast majority of all oil drilling and shipment is controlled by the Qusayni National Oil Corporation (QNOC), which is owned by a cousin of Mehmet Behav.

Copper

For most of Qusayn’s history, copper was a relatively minor source of economic activity, though its history is very long. Accounts written by early merchants arriving from what is now The Soodean Imperium described markets filled with copper jewelry. While most assumed these goods were produced locally, some mentioned the use of long caravans bringing it to the coast from areas further inland, which some modern historians have taken as evidence that the mining of the southern hills for export began more than a thousand years ago.

During the 1970s, the Ali regime began to invest heavily in mining copper from the rich but isolated reserves in the southern hills near Umcara. According to inner government accounts, Ali saw copper mining as an alternative to pure reliance on oil and a more direct means to industrialize the country. Copper production in the Socialist era was often low and inconsistent, governed primarily by small surface mines and smelted in “backyard furnaces.” Soon after economic liberalization in the 1990s, however, foreign firms began to investigate the possible gains to be made from the country’s rich but underused reserves. What followed was a dramatic expansion of strip mining and open-pit mining, as most of the copper reserves are relatively close to the surface. These large mining facilities are supplemented by smaller-scale, semi-legal operations, including the sifting of rivers for alluvial deposits and the digging of small shafts.

Both types of operations have attracted criticism for grave abuses of workers’ rights, including frequent accidents, insufficient protection against dust and chemicals, and low, inconsistent wages. Environmental degradation has also been a major problem, as large areas of jungle are burned, bulldozed, or clear-cut to make way for surface mining operations. In several of the smaller mines, investigations by independent NGOs has found evidence of unpaid child labor, though the Qusayni government has refused to comment on this matter.

Fishing

Because most of Qusayn’s soil is arid, and rainfall is inconsistent even in the winter monsoon, the recent population boom has been supported primarily by an expansion in fishing in the Meditethrhean Sea. Along the immediate coast, most fishing is still conducted by individual families in small motorboats, but in the last fifteen years there has been a major increase in the size and number of large trawlers, with much of the catch being sold for export. Poor regulation of the fishing industry has resulted in the depletion of fishing stocks in Qusayni waters, a source of concern for neighboring countries like Xiangshu.

Under Hemithean international law, Qusayn’s exclusive economic zone extends out to a distance of 200 nautical miles, or 370.4 kilometers. In 2010, as a response to overfishing in its own coastal waters, the Qusayni government unilaterally extended this out to a distance of 400 nautical miles, or 740.8 kilometers. This new boundary is not recognized by other Hemithean powers, and has been the source of occasional clashes between Qusayni trawlers and Soodean long-range factory-fishing ships. The regulation of Qusayn’s fishing industry, both in containment of territorial waters and control of overexploitation of fishing stocks, has been a major topic in the Community of Meditethrhean Sea States, of which Qusayn is a member.

International Trade

Ever since the opening of the economy in the 1990s, most of Qusayn’s international trade has taken place with developed economies in Euryphaessa and the other Western Continents. Within this category, Libraria and Ausitoria take the lion’s share of Qusayn’s exports, and supply a large portion of its imports. Maverica, Firmador, Erusuia, and The Soodean Imperium, Qusayn’s main trading partners during its Socialist era, have since fallen in proportional terms, but trade with Erusuia and Maverica has picked up in recent years.

Demographics

According to the last official Qusayni census, which was held in 2008, the country has a population of 38,510,974 people. A more recent publication by the International Hemithean Center for Demographics held that the population would be close to 45 million in 2015, though some experts consider this estimate slightly high. Population growth over the last ten years has averaged 2.2%, though it has varied over the country’s area, with faster increases in the cities and population declines in some rural areas. This is believed to be a result of immigration to urban areas, though high attrition due to lack of medical services and out-migration of impoverished peasants are also cited as reasons for the rural decline.

Ethnic Groups

The two main ethnic groups in Qusayn are the Alasedites and the Harudin, which make up roughly 87% and 11% of the country’s population, respectively. Though classified together by most outsiders as “Rheans,” the two ethnic groups harbor significant tensions against one another, which has been a source of instability in recent history.

The Harudin are descendants of the country’s original population, and are considered by some to be an indigenous group. The earliest archaeological records of their presence suggest that they first arrived on Rhea around five thousand years ago, near 3,000 BCE, though some scholars have disputed this by claiming that they arrived much earlier. It is believed that the first arrivals were indigenous fishermen from the south coast of Firmador carried off to sea by the strong southerly winds of the winter monsoon, and who may have returned on the northerly summer wind to alert others to the discovery of land across the strait. Whatever its origins, the Harudin population soon spread through the continent of Rhea, with some settling on the coast in fishing villages while others wandered further inland as nomadic herdsmen. By the time traders from Tethys “re-discovered” the Rhean coast in the 2nd century CE, it is reported that the Harudin population was still semi-nomadic but very widespread.

The Alasedites, by contrast, are the descendants of Southwest Tethyans who settled in Rhea from the 2nd century onward. The early settlements were of very small size, and usually temporary, but in 775 a permanent trading town was established near the modern city of Diyyah. From that time onward, the size and number of Alasedite settlements steadily grew, fed by a thriving trade network in the Meditethrhean Sea. From the 16th century onward, as Euryphaessan colonists began settling in Western Tethys in rising numbers, Alasedite migration to modern Qusayn made a proportionate increase as the indigenous population fled from fear of disease and persecution. Exact records are still hard to find, but when Firmadorean soldiers conquered 1752, they reported that the population along the coast was majority-Alasedite.

In spite of the ethnic groups’ common regional origins, Alasedite-Harudin relations have been the site of long and serious tension. The first Alasedite explorers described the natives they encountered as “desert barbarians,” contrasting their isolated tents and huts with the luxurious palaces and temples they had known in their homeland. With access to the bottleneck on Meditethrhean trade, later Alasedite settlers held disproportionate wealth in their settlements, and by the 9th century many held Rhean natives as slave-servants, though there were also isolated examples of Harudin individuals rising to positions of considerable influence. The arrival of Firmadorean colonists in the 18th century, however, exacerbated matters further; in a classic practice of “divide and rule,” the colonists used the generally privileged Alasedites as intermediaries, expanding the system of palace servitude into organized plantation slavery and dispatching bands of armed Alasedite mercenaries to quell tribal resistance in the interior. Bvordxan rule continued this system with minor changes. The transfer of Kussein to Chattakang rule in 1920 brought with it a drastic leveling of ethnic relations, including the complete abolition of slavery, but the wealthier and more metropolitan Alasedite population remained disproportionately wealthy compared to the isolated Harudin.

Ethnic inequality of this sort remained in place after Qusayn’s independence. Only a few months after gaining independence in 1952, the Qusayni government passed apartheid-style laws providing for the segregation of Harudin individuals within the country’s cities and effectively preventing out-migration from the country’s tribal interior. Outright segregation was abolished under the Socialist government that followed, but President Ali’s upper government consisted almost entirely of Alasedites, and his policies of “rural modernization” cut apart the fabric of traditional Harudin nomadic life. The most infamous of these policies, the failed 1974 Collectivization campaign and the civil war that followed, was particularly devastating for the nomadic Harudin. To this day, tensions between the Alasedite majority and the Harudin minority remain a severe source of tension and divisiveness in Qusayni society, with some foreign academics labeling it Qusayn’s deepest problem.

Migration Patterns

For most of its recent history, Qusayn has been a net sender of immigrants, with more people leaving than arriving every year. Historically, a common destination for Qusayni emigrants has been Firmador to the north, where prior colonial ties and the presence of an Alasedite minority have facilitated cross-strait settlement. Most Qusayni immigrants to Firmador are of the Alasedite ethnic group, and they are generally better-educated than the average Qusayni, traveling abroad in order to seek better economic opportunities. Upon arriving, however, many find that discriminatory policies enacted by the Firmadore majority make it difficult to find secure, high-paying work, and many end up in lower-class jobs.

After the beginning of the Civil War in Firmador, the common migration pattern has reversed. Major political unrest in Firmador has made it an unreliable destination for educated migrants, and fighting along the southern coast has actually driven many residents of Firmador to flee across the strait to Qusayn. Exact numbers and demographics on this group are still unclear, but it seems that many are ethnic Alasedites rather than Firmadores. Additionally, a large percentage arrive in Qusayn without proper documentation, and even those with papers find themselves with limited opportunities for housing and work. As a result, homelessness has risen dramatically in Qusayn’s main coastal cities, and the Behav regime is debating the implementation of harsher laws against immigration.

Out-migration, both legal and illegal, is also common along Qusayn’s inland borders. According to estimates by Friends Of Esperance, Hemithea’s leading NGO on refugee issues, approximately two out of three illegal Qusayni emigrants are of the Harudin ethnic group, which makes up only 11 percent of the overall population. In some areas of the border, drug smuggling is also a major issue, especially in the form of processed and unprocessed coca leaves which are grown in the jungle highlands of Southern Qusayn. The Qusayni government has declared its intention to reduce illegal emigration and stamp out the coca trade, but due to the vast length of the inland borders, enforcement is very rare.

Culture

Language

The dominant language in Qusayn is Alasedi, which is also the language of the Alasedite minority in southern Tethys. The version in Qusayn is actually a distinct dialect, which is generally mutually intelligible with the Tethyan dialect but includes many differences in pronunciation and vocabulary. Alasedi is written from left to right in a sweeping calligraphic script, the style of which is believed to be derived from the ancient Esfahadian civilization in what is today The Soodean Imperium. Iskander Ibn-Sadat, the leader of the early revolutionary movement, initially spoke of plans to adopt a Romanized alphabet in order to increase literacy, but this plan was later abandoned as a “concession to the Colonial system of writing.”

Religion

The main religion in Qusayn is Salahism, which was brought to Northern Rhea by merchants and missionaries from southern Tethys starting in the 8th Century CE. Salahism is not officially a state religion - the first independent government declared that it would treat all religious groups equally, and the Socialist regime displayed a constant, if very halfhearted, promotion of secularism – but it is practiced by the vast majority of Qusaynis, and holds considerable influence in societies, especially in rural areas of the north. In cities, however, this may be likely to change. The new-rich upper class still consider it fashionable to make a public impression of faith, and clergy members with connections to the Behav family have amassed considerable wealth and power, but public surveys show that the influence of religion is declining.

In the southern and inland areas of the country, local Harudin populations practice a unique sect of Salahism which incorporates traditional animist qualities including animal sacrifice, the ritual use of coca-based hallucinogens, and a belief in witchcraft. The Alasedite majority along the coast, which adhere to the more orthodox Reformed Sect practiced in Southern Rhea, typically do not consider the inland sect to be a “true” form of Salahism, and tensions between the two interpretations of the religion have been a major catalyst in inter-ethnic conflicts.