Bu

The Bo (袍, bo) is a sleeved garment with a round neckline, opening at the front

Uniforms

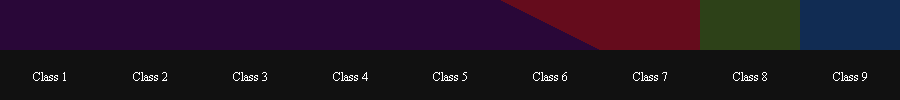

Some time between the Meng restoration in Themiclesia in 543 and 581, the bo was sanctioned by the royal court as a regulated quotidian garment worn by men of rank, who were required to wear the correct colour that corresponded to their pem (品) rank, numbered 1 (highest) through 9 (lowest).

The pem system, separate from the lrit pay grade, was imported from Menghe and ranked offices by their relative prestige rather than strictly their position in the hierarchy. To be appointed to an office of a given pem rank, the candidate had to possess the same pem rank or higher, and this was conferred by aristocarcy. It was quite possible for an office to have a high pem rank and few or no subordinates or influence in public policy. While all public officials by the 6th century received pay via a lrit pay grade, the pem rank was only accorded to offices deemed to be within the sphere of gentry. In 581, there were 572 offices and their holders that had a pem rank out of possibly 10,000 – 15,000 who drew salaries according to a lrit pay grade.

Most military officers were royal bureaucrats called to command troops on the eve of battle, and as such, military posts normally did not have a separate pem rank. There were a few peace time military posts with pem rank, perhaps not more than 100, and their holders were also ordinary bureaucrats who expected to be promoted one day to a different and probably non-military office. Of the few permanent positions known, both a "thousand-commander" (commanding about 1,600 troops) and a "five-hundred-commander" (about 400 infantry or 120 cavalry) held a 9th pem, the lowest possible rank on the pem scale. Historians know that "petty minor officers" (少微吏) existed under them, but such went almost completely unrecorded not being selected from the gentry and leaving no "list of offices held". It is through these "lists" that much about ancient government is known.

According to the colour laid out above, the senior military officers in peacetime would have worn a deep blue bo as they were already at the bottom rank. Petty officers down to the rank and file seem to have wore pale blue (縹, pru) or home-brought clothes. A new ranking scheme emerged in the late 6th and early 7th centuries based on metal pieces worn on soldiers' belts, which seems to have recorded both battle exploits as well as minor position. These makeshift insignia seem to have emerged out of necessity as all the major colours, as well as the right to wear brocade, embroidery, and jewellery, had been assigned to officials by strict sumptuary laws. There are a many surviving examples of such decorated belts dating after the 590s or 600s, and most such insignia are small nail-like pieces of metals hammered into the leather belt, while some took the shape of semi-circular or circular loops. A bas-relief design could be further applied over the metal surface.

In history, soldiers were often said to "look at their belts" when boasting about their experiences. While the re-discovery of these insignia-laden belts has grounded our understanding of that expression, it has proven very difficult to interpret the meaning of these insignia, owing in no small part to their poor condition in archaeological finds. Rand proposes, as a rudimentary hypothesis, that the nail-like medallions signified battle records, while rings puncturing the belt signified office, noting that only one example has been found of belts with 13 metal rings, and it seems to have been intentionally preserved in a leather pouch at burial, with the text "left flank" (左首). Most belts had anywhere from 5 to 7 rings for suspending utilities, but those with more than this number often show better workmanship. He is therefore led to conclude that 9 rings or more signified a petty officer of some kind, and 13 rings was probably worn by a commander of 100.