1891 Nobleman Insurrection

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

| 1891 Nobleman Insurrection | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

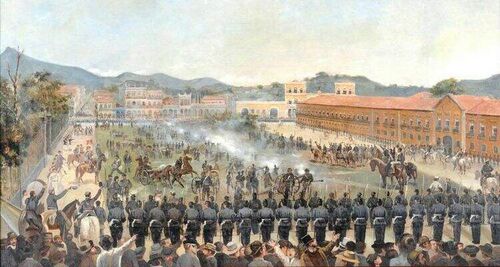

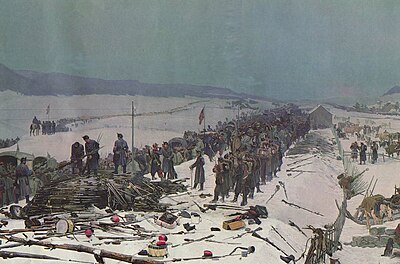

Disarmament of Forelis Insurrectionists after their surrender in late 1891 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Imperial Government-Nobleman Insurrectionists | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 4,000,000 (peak)[b] | 234,000 (peak)[c] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 19,234+[d] | 48,000+ [e] | ||||||||

| Between 100,000 to 500,000 civilians killed. | |||||||||

The 1891 Nobleman Insurrection, or often reflected upon negatively as the "2nd Nobleman Rancor," was a short-lived unsuccessful military revolt lead by Count Ortwin Baldo Braune and several other moderately ranked secessionist Nobleman Families (and their allies) against the Imperial Government in Reichsstadt. Noblemen from the northwestern Forelis Province officially revolted on May 22nd, 1891, with Count Braune leading several surrounding realms in declaring a state of rebellion; on that same day, the combined armies of Count Braune and his allies launched a series of swift military campaigns against neighboring loyalist realms.

In the prelude of the uprising, Count Braune dispatched hundreds of letters beginning at the start of the month directly addressing the Emperor along with hundreds of other Nobleman Families. Each letter contained a series of declarations that would later go on to be known as the "Letters of Declarations." In the Letters, Count Braune passionately made his case to the recipient, often including personal letters addressed to the recipients, and outlining his plan of action in the months to come. In one of the paragraphs outlining his plan of action, the Count addressed himself as "King" of the new "Kingdom of Braune," declaring that his kingdom and its allies planned to secede from the Empire because "repairing its declining health internally is no longer a viable option." The Letters also encouraged other noble realms to join their cause and stated their end-goal was to "emancipate the Empire their forefathers built from the revisionist filth who've irrevocably perverted Imperial Authority and Noble Rule." In an attempt to assassinate the Emperor and send a clear message, Count Braune's Letter to Emperor Charles I supposedly contained an unknown poisonous powder. Believed to be the recently synthesized poison Ricin, the Emperor's Secretary was the first casualty of the Insurrection, almost immediately becoming violently ill after flipping through the documents. The envelope never reached the Emperor and the staff who responded to the calls for help were treated - the Emperor's Secretary was less fortunate and died. Before destroying the contents for decontamination, a handwritten note was supposedly discovered with only one sentence written on it: "Ich hoffe Du verreckst, Schmore in der Hölle!" Translated to English the message means, "I hope you died, Burn in Hell!"

Prelude To Secession

At its core, the central conflict leading to the 1891 Nobleman Insurrection were the historical disputes held by a significant faction of Noblemen which argued that Imperial Authorities had eroded the legitimate rule of Noble Dynasties stemming as far back as 1453, decades prior to the 1502 Nobility Civil War or "1st Nobleman Rancor". Nobleman back then argued that Imperial Authorities, namely the Emperors of the time, had begun unfairly burdening the Nobleman Class while also abrading privileges enjoyed by their forefathers for generations. Modern Noblemen argued that not only were their predecessors proven correct in their assessments in the immediate aftermath of the civil war, but that the swift reckoning of Imperial Authorities post-civil war had been so harsh that noblemen had little reason but remain scornful of Imperial rule.

The Feud Between Nobility and Royalty

Much of the Nobleman Class' ire originates from Imperial governmental reforms throughout history, the first of which occurred prior to the 1502 civil war. Emperor Kaufmann Albert Walherich saw that corruption among the nobleman was not only pungently abrasive but had grown so egregious that noblemen had even began openly dealing with foreign adversaries south of the Empire. Believing a firm hand cowers the weak and inspires the strong, Emperor Walherich instituted a number of reforms in 1453 aimed at restoring not only public order but also putting fear in the hearts of would be traitorous nobleman. Emperor Walherich personally punished numerous nobles along with instituting wide-ranging reforms in order to send a message to those within the Nobleman Class who continued to subvert Imperial Authority. Aside from several noblemen being stripped of everything, including their lives in some cases, reforms to oversight and installing new rules regarding nobleman financial decisions on their populace were enacted. Although this made the Emperor very popular among the average family, the Nobles (namely the land ruling ones) were exceptionally enraged by the reforms. Generating wealth was largely needed during the time as minor conflicts with neighboring nobles was common. Living a life of luxury was also important to most nobles, some of which had no need to fear conflict and instead wished to amass great wealth for personal reasons; between owning properties, buying luxury items, forcing lower classes to serve them as if they were slaves, all that and more required Nobleman to enact unfair taxation and regulations that steadily became common in the lower realms of the Empire. In the following years after Emperor Walherich's reforms, minor protests and revolts occurred ranging from full-blown wars[f] with Imperial Authorities to some nobles outright declaring their intent to rebel in some extreme scenarios; a few realms, such as the former Dresdner March, went as far as pledging their allegiance to the Empire's neighbors before facing Imperial wrath. Although Emperor Walherich's reforms are sometimes called into question for how effective they truly were at stemming corruption, historians mostly agree that Emperor Walherich's reforms were the point of origin for the longstanding feud held between Imperial Authorities of the Reichsstadt and the historically influential Nobleman Class. In the long run, historians often credit Emperor Walherich for helping to quell Imperial instability, increase Imperial authority while it was at its weakest, and generally improve the quality of life of citizens within the Empire.

Between 1504 and 1890 were a number of events that gradually if not exponentially reduced the influence and authority nobleman held within the Empire. Reforms enacted in 1504 by Emperor Walherich's grandson, Emperor Jochim Reiher Walherich, severely impacted the Nobleman Class' authority within the Empire. Although advertised as Imperial Government reforms intended to repair the country as a whole, Emperor Jochim's reforms post-civil war (with his predisposition against nobleman since childhood) was clearly intended to punish and defang the Nobleman Class according to historians. In a moved aimed at ripping away their powerbase, the Empire's internal borders were redrawn and a new provincial system was implemented. This process not only required the redistricting of Noble Realms a great deal, it lead to the dismantling and creation of numerous Nobleman Houses. Duke Anselm Pankraz Schultheiss' Dukedom was the greatest to be affected. Given its position as the leader of the rebels during the civil war, the Schultheiss Dukedom was completely dissolved[g] and replaced under the direct rule of the Royal Family's 3rd Prince, Prince Hartwin Theudoricus Walherich. Under the new Imperial Province System, and under the authority of the newly created "Walherich Principality," the former Dukedom's ruling class was spared no quarter. On the local level, Prince Hartwin became the Empire's personified retribution to the northeastern nobles, continuing to not only punish and execute disloyal nobleman who hadn't been dealt with yet, but also stamping out the deeply engrained anti-Imperial culture that had began to flourish within the last two decades. Prince Hartwin is noted by historians for being ruthless with his regime's predecessors, believing them to often not live up to their responsibilities and ultimately resulting in their systematic cleansing. Over time a number of policies and revitalization efforts put in place by the Prince to refranchise the people along with installing perceivably righteous nobleman steadily reversed the disloyalty seen throughout the province's citizenry. Prince Hartwin believed the realm could be healed and reintegrated peacefully into the Empire over time, and so spent his life working to make that belief a reality until his death in 1546[h]. Imperial reforms, namely the Provincial System, brought with it a number of changes to the Empire's decentralized governance. Provinces would be governed, not ruled, by Dukes or their betters (such as Prince Hartwin). These provinces would be overseen by Imperial Officials known as Viceroys, whom were appointed by the Emperor himself to act as an Imperial overseer. Regardless of reasoning, inter-Imperial warfare was now outlawed unless the noble could prove it was out of self-defense. Oversights intended to combat corruption and degradation of the population also proved effective at hampering the Noble Classes' powerbase. Ultimately, these and other reforms were made into Imperial Law through the Empire's newly drafted constitution.

Prelude To 1891's Insurrection

Emperor Landebert Konrad Thorsten's "1865 Reformation Law" is historically recounted as the root cause of the Nobleman Class' revitalized outrage prior to the 1891 Insurrection. Although significant reforms to the Imperial Government were put in place during the last three centuries, most of these reforms slowly degraded Nobleman Authority over time and revolts against them were successfully put down. Nobleman, even the non-land ruling Class, were far from being uninfluential and retained significant power even though much of their autonomy had been withered away when compared to nobleman autonomy in 1504. Since the end of the Hartwin Principality and rise of the Rothenberg Dukedom, Forelis Province has experienced the brunt of Imperial and Duchy reforms aimed at curbing nobleman authority to abuse their citizenry. The back-and-forth clashes between the Nobleman Class' historically relevant ruling powers and the Emperor's cultural and constitutional powerbase came to a head often, but none were as heated as the 1865 Reformation Laws.

Briefly explained, the 1865 Reformation Laws enacted by Emperor Thorsten once again revisited the authority nobleman, especially land governing nobles, had when administrating their territories. The most controversial Law within the Laws was the dismantling of nobleman controlled standing armies within the Mainland, meaning nobleman realms on Mainland TECT could no longer retain military forces that could hope to resemble that of a standing army. Although policing forces were exempted, in the same section they're exempted from the law, a strict list of guidelines prevented abuse using loopholes that would allow for militarized police units. If that weren't bad enough, the Laws made it all but illegal to ignore the civil rights now promised to citizenry by those of higher class, namely the Nobleman Class. Imperial Supreme Court decisions on the matter already upheld that citizens held rights outlined in the TECT Constitution regardless their standing in society, and that discrimination by Class (without legal justification) was illegal. All these new Laws made Nobleman question what exactly did they have left as leverage within the Empire. If earning an income is becoming even more difficult, if privileges enjoyed since the Empire's foundation have eroded away, and if nothing is stopping the Empire from enforcing its will upon the Nobleman Class by gunpoint, what made Nobleman different from regular citizens?

Historically speaking, by this point in Imperial history, the Empire had united the entire continent under its banner. Although some resistance remained in the newly annexed southern regions, the Empire had finally reached its greatest triumph. Now nearly a century later, newly patriated citizens and those born after unification had at least reached some equilibrium thanks to the Empire's stabilization efforts with everyday citizens. In fact, many Emperors dating back to Walherich I realized the same thing Maximus Forelis did almost three millennia's ago: Nobleman may govern empires, but the citizenry are what make up empires. Historians believe this viewpoint is what eventually led to the four century long conflict between the Empire and its own Nobleman Class. So although the Imperial Family may have been greatly disliked and lost much trust with many if not most nobleman, popularity among the masses, even in more newer territories, soared to new heights. As nobleman continued to swipe back in any way possible, their popularity with their own people declined. So much so that in some extreme examples, nobleman faced mobs of angry citizens each time a new policy negatively effecting them was passed within the realm - something unheard of four hundred years ago. The power struggle among nobleman became fiercer as many swapped their allegiance to the Empire for not only survival but also to hold onto what power they had left. Others continued unrelenting to the new trends, resisting Imperial Authority until the bitter end. Bitter ends happened frequently with many stepping down due to their lost authority or wealth, others removed by force for breaking Imperial Law, and some outright cashing out and giving up their claims to territory in order to strive for different goals. As the staunch conservative faction of nobleman continued to dwindle, so too did their options, leading to desperate measures.

Braune v. HRIM Thorsten Government (1885)

In what is said by historians to have been the final peaceful attempt by disenfranchised nobleman at refuting perceived injustices in Imperial Law, Count Ortwin Baldo Braune filed a lawsuit against the Imperial Government, namely the Emperor, in the Empire's TECT Constitution 2nd Imperial District Court. Count Braune, in the opening section of his lawsuit, accused the Imperial Government of violating the rights and privileges held by Nobleman, some of which were grandathered into the Empire's newest Constitution. Filed on April 3rd, 1885, the case was first argued in front of a panel of five Forelis Provincial Judges whom vetted the lawsuit's merits in both the Provincial setting and the Imperial District setting. Count Ortwin Braune's case was found to be of merit by all five judges, arguing that the case not only belonged in Imperial Court but was also of considerable standing to be heard. Writing the Opinion, Judge Wandal Thälmann wrote, "Count Braune's arguments, which do take aim at Provincial Authorities and the laws they have passed previously, sets its true aim at Imperial Authorities for whom the accused offenses originate from. Said powers, stemming from the 1505 Constitution and recent 1802 overhauls, are accused of being abused by Provincial authorities on behalf of the Imperial Government. Furthermore, arguments regarding rights of citizens upheld in the Imperial Constitution verses the historic privileges enjoyed by the Nobleman Class culminate as both a unique challenge to the Imperial Constitution and a dangerous precedent requiring higher court clarification. Never before has there been a more concise and thought provoking challenge to the Empire's Constitution in its nearly four centuries as Law."

A month later on May 12th, Count Ortwin Braune's case was heard before another panel of judges, this time in 2nd Imperial District Court. Arguing his case alongside his team of lawyers, Count Braune made several key points the center of his legal challenge to not only the 1865 Reformation Laws, but also brought into doubt how the Imperial Constitution viewed Nobleman. Among his challenges brought before the court, the Count argued the prohibition of nobleman retained militaries was a violation of his and his realm's Imperial and Provincial Rights, arguing that their right to bare arms and right to self-defense as a recognized Imperial Realm were violated. Taxation and lower realm autonomy was brought into question as well, with one of Count Braune's lawyers arguing that although Imperial law supersedes Realm or Provincial Law, the Imperial Constitution delegates local powers and taxation to local authorities, namely the Provincial Dukedom or the lower realms. Imperial Authorities outlawing or micromanaging the Province's or even the Countdom's taxation methods would be unconstitutional if the Count's lawyer was to be believed. Although a longshot, Count Braune also argued that Nobleman Authority has been unrightfully disturbed or even eroded, using Decrees from Emperors as far back as Maximus' Household to prove his argument that Nobleman were a cornerstone of domestic governance and held autonomous powers as thus within the Empire.

Arguing for the Defense was the Ministry of Justice's legal team alongside the Emperor's own personal legal counsel. Although the Emperor could have halted any court case with a swipe of the pen, doing so would present terrible political optics and fail to counter the claims against the Empire - it would even prove the Count's case for him in fact. Thus merely using the Emperor's power to void any such legal challenge was avoided for the time being. Ministry lawyers immediately dismissed the arguments made by Count Braune and his legal team. Their argument was that while Nobleman weren't referenced by name within the Imperial Constitution, realms were covered within Article Two under Provincial & Local Jurisdictions. Arguing the rights of Nobleman as if they were the Realm they represent was, according to the MOJ's lead lawyer, "An act of self-preservation for illegal activities designed to make murky Imperial Law and confuse the court on the perception of whether the man in front of you is human (like the rest of us) or the land he governs." The argument essentially bottled down to nobleman and realms, having changed politically since the 14th Century, not only were separate entities but that powers they once held (such as those back in ancient times) were no longer legal nor relevant. As for the right to bare arms and self defense, the MOJ's third lawyer argued that not only did Realms/Provinces lack said rights, but even if they did have said rights, those rights had not been violated since Provincial Rights were found in Article Two (regarding territories of the Empire) and not Article Three (rights of the citizens) which was being referenced. "The fundamental right to bare arms - protected by the Constitution and the Emperor's Decree - explicitly states that citizens are guaranteed these rights. Although the Count is a citizen and his rights to self-defense have not been challenged in the least, it is the opinion of the Defense that Count Braune only utilizes his civil rights in convenient arguments and not in terms of the Law itself. Even if the Realms had these specific rights, which it does not but rather authorities, these rights were not violated given that the 1865 Reformation Laws outlined militarized units were no longer needed and only policing forces were required for a Realm or Province's security. Security of the Realms and Provinces have not been degraded in any way shape of form given that no foreign nation exists to attack them, and inter-Imperial warfare has been illegal for centuries." Lastly, the Emperor's own lead counsel chimed in, stating "His Imperial & Royal Majesty the Emperor, according to his birthright, to our very culture and Constitution, reserves the power to make law and Decree as he pleases. And in his Constitution it is clearly written where the separation of powers begin and end. Imperial overstep, as explained by my Ministry colleagues, has not occurred nor have these accusations been proven to be true. It is only possible for overstep when the Emperor exceeds his people's approval, to which has not happened given Congress', the Courts, Provinces, and the general citizenry yays verses the minority nays heard from naysayers."

2nd Imperial District Court, in a 5-1 vote, found in favor of the Imperial Government on all but one count. The panel of judges found that the Imperial Government in one specific scenario overstepped the Province's authority when it came to establishing its taxation codes. Writing the opinion for the majority in the 2nd Imperial District Court was Chief Judge Ekkehard Höfler who shoots down all but one of Count Braune's arguments. "It is the opinion of this court that Count Braune's legal arguments fail to meet this court's low-bar when considering the legality of the Imperial Government's powers under the Imperial Constitution. Although justified in seeking relief, and held in respect for the brilliant legal challenges presented, Count Braune's arguments run afoul of the Imperial Constitution, namely its second article. Article Two of the Imperial Constitution articulates the powers relegated to the Realms and their Lords - beginning with the central authorities within the Empire, Provincial Dukedoms, and their Lower Realms. This court rejects the Count's argument that Realms hold the same rights as individual citizens posses, and refers back to Article Two which clarifies actions conducted by Lords in official capacities - or other stately duties - are not the same as one's personal cognizance. Rights outlined in the Imperial Constitution's Third Article are not the same as the authorities/powers outlined within the Imperial Constitution's Second Article. However, this court finds in favor of Count Braune in arguments challenging Imperial Government overstep into Provincial matters of law. In (once more) Article Two, Provincial Dukedoms are the supreme central authority with delegated governmental authority. Taxation falls within the scope of their abilities, and unless in violation of Imperial Law or His Majesty's purview, the Imperial Government is restricted from altering Provincial Tax Code. Although the Imperial Government can impose its own tax code, and universally the Emperor has the innate authority to Decree/Issue taxation as well, the Imperial Government itself cannot modify Provincial Tax Code without legal justification to do so. Doing so is a violation of the separation of powers outlined in Article Two which clarifies the duties, powers, and responsibilities of Provincial Governments and the Imperial Government."

Count Braune's defeat in Imperial District Court was largely expected, yet it still sent shockwaves to supporters of the Nobleman Class as well as Provincial Dukedom Governments. Predictably, what remained of Count Braune's legal case was appealed to the 2nd Imperial District Court's Appellate Court a week after the previous court verdict. Once more Count Braune was defeated in court with 2nd Imperial District Court's Appellate Court Judge Michi Meyers writing for the majority, "2nd Imperial District Court is found to have ruled correctly in this case. This court sees no error the previous ruling didn't already rectify." Distraught, Count Braune and his supporters were left with little to no choice but appeal to the Imperial Supreme Court, who could at least rule in their favor and potentially the decision could convince the Emperor not to overturn that verdict. The Supreme Court of The Empire of Common Territories accepted the emergency case and on July 5th heard the first oral arguments from Count Braune's legal team. Throughout the next two weeks, both Count Braune and the Imperial Government argued their cases to the nine Supreme Court Justices. Historians, including courtroom/legal researchers, describe the significance of the legal battle as one full of both legal dueling and emotional outbursts. In one famous moment of oral arguments with both parties present, Count Braune had a verbal outburst against a rarely seen female Imperial Government lawyer, Irene Haberkorn, whom he accused of offending him by disrespecting his title and honor. Women during the time were expected to be obedient to men, especially those of influence like nobleman. The notoriously sexist and classist Count Braune was so irate with the female lawyer that in slamming his cane against a table, it snapped in two, sending shards and the other half towards the Defense team "Wench! You dare address me in such casual manner even though you know full-well whom you speak of!? You should have never stepped into this institution to begin with, but now you mock your betters?! I will not standby as this whore dares to defame my honor!" Depicted in the courtroom's official trial painting, Count Braune is seen being held back by his team of lawyers while he shouted, holding half of what remained of his cane. Supposedly, in the immediate moment after the verbal abuse, the Count was escorted from the courtroom by Royal Guards and Capitol Police after he climbed over the railings surrounding his legal team's seating and quickly approached the Defense's seating with his splintered cane raised to a position above his head ready to strike. Similar heated outbursts from even Count Braune's own legal team continued until the final day of oral arguments. On July 26th, a week after deliberations began, the Imperial Supreme Court found in favor of the Imperial Government on all arguments in a 7-2 vote. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice Fulchard Arne Grünberg wrote, "This court, in its long deliberations, finds the Imperial Government acted accordingly and is not in breach of Imperial Law. In agreement with 2nd Imperial District Court's original opinion, this court concludes that the Imperial Constitution's Second Article articulates the powers and responsibilities held by all governing entities within the Empire. The explination from the 2nd Imperial District was the correct one, which stated Article Two of the Imperial Constitution clarifies the powers held in which order from the Imperial Government, down to its Provincial Dukedoms, and concluded in that Imperial Duke's Realm. Imperial Government bodies were not found to be in violation of the law purely because Imperial Nobleman whom govern their respective territories cannot be personified nor defined as the Realm itself according to Article Two's wording. Furthermore, Article Three, which articulate the rights of citizens, also dictates whom are citizens and whom aren't. Lastly, in Article One and Two, His Majesty the Emperor holds supreme authority in matters of State and Government. The Imperial Laws passed by His Majesty were Decrees by nature even if they were sent to the Imperial Parliament for corrections and ratification."

Reactions to the monumental case from both sides were almost immediate. Imperial Government officials and even the Emperor applauded the decision as a "victory for the rule of Imperial Law and Order." Average citizens, who celebrated the verdict, held large festivities throughout the Empire - this celebration would not last long however. Count Braune, his supporters, and the staunch supporters of the Nobleman Class, were furious. Protests within territories aligned to the Nobleman Class' cause sprung up overnight, often becoming violent even though limited to certain jurisdictional pockets. In many cases local authorities refused or even supported the protests, forcing Imperial or Provincial authorities to act. Immediate consequences of the ruling were felt all over the Empire. Setting Supreme Court Case Law, Nobleman throughout the Empire were now forced to accept the definitions that separated them from their titles and Lands. Before, Nobleman enjoyed privileges associated with their titles that essentially allowed them to live daily not as the man named after a territory but the territory named after the man - they were not men but the Realm itself. Although this ruling technically protected their civil rights, this new separation of powers case law put an end to Nobleman conflating their authorities in personal matters - essentially one huge hierarchal demotion. Taxation from Nobleman in their Realms was protected in Lower Realm governance by the ruling as well. Unless the Provincial Duke did or say otherwise, Realms could make changes to their own tax code at will; this ultimately resulted in tax codes changing quickly with some parts of the Empire being heavily taxed in response to the ruling. The elimination of Realm militaries also went into affect, making it illegal for Nobleman to control personal militaries, regardless if it served the Realm or them personally. Although Nobleman successfully found loopholes around this part of the ruling, the practice itself would officially end after the 1891 Insurrection. Most importantly, the long-term consequences of the ruling was that Count Braune, along with his supporters, realized they were left with no other choice than to resort to their last desperate option if they were to sustain their way of life. That last resort was rebellion.

Insurrection & Secession

Talk of insurrection came hours after the 1885 Braune v. HRIM Thorsten decision amidst protests held by Noblemen and their supporters. Although many in the streets talked of civil disobedience or even rebellion in some form, the more serious actors behind the scene began formulating rebellious plots against the Empire. In the days following the decision, nobleman at odds with the ruling exchanged letters and met in person to discuss the future. While many were fearful of their territories and powers being eventually robbed from them, a great many had grievances as old as the disputes dating back the 16th century. Many ideas were floated amongst the private circles of nobles, many suggesting acts of protest that would put them at odds with the Empire, such as withholding taxes and denying Imperial Authorities access to their lands. Others opted for a more bloodless route, suggesting noblemen within the Empire establish a voting block within the Empire's Parliament. An idea that would theoretically uproot the power Imperial Authorities had domestically until a new Emperor could be groomed to their favor. Nobles such as Count Ortwin Baldo Braune had different, more radical ideas concerning their future. Count Braune was extremely vocal given his position as the accuser in court, and thanks to his political maneuvering with other nobleman he was crowned the movement's de-facto leader. Publicly Count Braune was vocally against the ruling and vowed to continue fighting for Nobleman rights. Behind doors, however, Count Braune decided in the immediate aftermath of the court case that there was no other option left but rebellion. Braune was by far the largest proponent within private circles that noblemen needed to stand their ground, banding together militarily if that was their only recourse. In some of his earliest letters concerning the future of their realms, Count Braune is seen recruiting his most loyal allies while also describing his position to those on the fence in black and white. "There is no greater meaning to life than for a man to defend his own private kingdom. Whether that man be of lower birth defending his castle from unruly invaders, or Nobles such as ourselves defending our realms from unjust attackers in the Imperial Government. If our supposed greaters within the Empire are beset to attack our very heritage as a people, our only recourse is none other than rebellion. - Count Ortwin Baldo Braune, 1885."

Protests & Homegrown Sabotage

Between the years of 1885 and 1890, Count Braune set out on a campaign of recruiting nobleman to his cause. Taking the time to meet with many of them in person and avoiding letter carriers he didn't trust with his life, Count Braune was meticulous in keeping his plot a secret from those outside the circle of conspirators. At the same time Count Braune's circle of rebelling nobles grew, so too did the political strife in all levels of governance within the Empire. Count Braune and his allies were behind a number of protests and acts of disobedience starting in 1886 designed to not only hurt the Imperial Government but also create dissatisfaction among the population. Taxes being submitted were found to be a mistake by the very Nobles who submitted them, causing significant delays in payments. Resources and goods sold to other territories whom needed them within loyalist lands were now suddenly facing "bandits" that would rob or disrupt the flow of commerce. Insurance claims alone began to skyrocket, leading to higher rates and often late payments. Although the acts then were merely blamed on political dysfunction stemming from the contested supreme court decision, and Count Braune's circle was hurt by the consequences as well, the pains felt by everyone within the Empire was just as great. Imperial Authorities were eventually able to deduce what was occurring by 1889, but by then it was too late as the Imperial Economy tumbled as a result of protesting Nobles. As a result, Imperial Authorities and the Emperor himself punished several realms, including ordering them to pay fines to help cover government programs designed to reverse the economic damage they directly caused. Of course these Noblemen sued the government as Count Braune did years prior, but to them the case would no longer hold significance because by time trail dates would occur those realms would already be in open rebellion.

Reactions to the sabotage conducted by Nobles is often considered double edged by Imperial historians. Although their goal of creating instability and materially harming Imperial resources were successful, the results often ended up negatively rebounding on Nobleman politically. For example, those among the population whom sided with the Nobles only grew more intrenched in their beliefs as a result of the deteriorating economy. Although rare, some did find blame in the Imperial Government of the current political and economic crisis facing the nation. Protests weren't rare within areas of the Empire concerning the economy, however, many blamed the Empire for totally different reasons than the rebellious Noblemen had desired. Within Noblemen aligned areas the protests were often massive, leading to largescale riots where Imperial Authorities were forced to take serious action at times because local authorities often condoned the violence. In 1890, as a final act of total civil disobedience, Count Braune and his circle orchestrated the largest summer of riots by pro-Noblemen populations the Empire had seen since the 1885 supreme court decision. Several cities burned continuously throughout the last three months of summer within the Empire, leading to millions of Imperial Dollars in damages and nearly a hundred dead. Neuenried, Count Braune's own capital, saw the largest riots as his supporters assaulted Imperial facilities and even burned several to the ground. Imperial Authorities were unprepared for the sheer size of the riots, forcing many Imperial and Provincial police forces to retreat to safer areas while military forces were authorized to assemble and assist quelling the riots. Imperial Authorities blamed the Nobles in the realms greatly affected during the 1890 Riots, with Ministry of Justice spokesman Theodoar Huffman proclaiming "Authorities within the hottest beds of instability may as well have held the torches themselves." Meanwhile the Nobles blamed the instability on the Imperial Government, Count Braune would later retort to MOJ officials by saying "The Imperial Government has set itself aflame and dares to blame local authorities for their ineptitude after chopping away at the roots of Imperial Authority - the Nobleman Realms. Is it not just of us to remove ourselves from the situation in regards to Imperial facilities then? Imperial Government Authorities have banned our armies, have made our oversight peasantry, and overstepped Noblemen for centuries now. If the Imperial Government wishes to police the people of Neuenried personally, don't ask me to do your job for you, send your own army to do it. Let the Empire enforce Imperial Law if it wishes it so badly."

Although Count Braune and his growing inner circle had succeeded in some avenues, historians believe the double edged sword hurt him the most. The Empire during this time had grown increasingly liberty focused, seeing republican forms of government more favorable due to the previously annexed southern nations in the latter half of the 18th Century. Although Imperial Officials were greatly concerned with this new political shift in the population, countermeasures by then Emperor Reiner Thorsten largely negated serious repercussions of the dynamic political shift. Successful in its own right, the Noblemen Class was largely to thank for Imperial success in diswaying the population from desiring the toppling of the Imperial form of government. A double entendre, the Nobles now overseeing the newly annexed lands were specifically chosen to quell any thought of dissatisfaction the population may have; many nobles would even go as far as excessive charity work to keep excellent public images. But the other side of the entendre was that citizens saw the Emperor and his vassals differently. While the Emperor was seen very favorably even among the newer citizens of the Empire, Nobles did not share the same image. Although many had bribed in one way or another for good public image, the worst off Nobles could not hide their negative images outside their territories. Fast-forward to present day, the actions of nobles would not go unseen as their greed and corruption harmed the general public. Count Braune's court case was seen by the vast majority of the population as another Nobleman Rancor, similar to the 1502 Civil War which was viewed negatively upon by the greater public when Noblemen were concerned. Papers at the time were critical of Nobleman activity, many of which pointed the finger at the local Nobleman for local issues. Although hurting themselves in the process, Count Braune and his conspirators succeeded in laying the foundation to their schemes. Nationwide instability and division soared by the time 1891 arrived, creating the perfect pretext for rebellion.

Rebellion

In the months leading to the beginning of the war, Count Braune and allies used the winter months to begin secretly stockpiling supplies and equipment. Meanwhile on the surface Count Braune had especially soften his rhetoric, even going as far as meeting with Imperial authorities to discuss methods in which both factions could "calm" their respective counterparts. So while the Emperor was fed good news from his staff concerning the disgruntled noblemen, said noblemen were quietly rearming.

By New Years Day of 1891, Count Braune and his most trusted allies had come to the conclusion that there was no turning back nor hope in repairing their relationship with the Empire. In the prior months to the following year, Count Braune and allies he brought with attempted high level talks with Imperial Authorities. While Imperial Authorities were under the impression these talks were further discussions on deescilation, the noblemen's true goal was a last minute overt attempt at finding compromise to their demands. Count Braune was especially determined to find some sort of settlement that could throw out the scheme he had put into place. These talks were said to have failed each time, even after proposed compromises were seen favorably by Imperial Authorities. Their failure, credited to a misunderstanding of the situation, was blamed on the mere fact that the Empire would not even hypothetically allow its vassals to sit at the same table for "peace negotiations" let alone dictate terms of such deals. The Imperial Government couldn't even fathom such a scenario even while actively discussing such peace terms with its vassals. While the Empire believed the talks were meetings to discuss settlements the vassals could make in order to calm the radicalization of their peers, the vassals in question attempting one last diplomatic approach before taking up arms had their entire reasoning killed before it could even be further argued. Citing a top level discussion with Imperial Authorities the week after Christmas 1890, Count Braune remarked in his private letters with his inner circle at how disillusioned prospects had become for a peaceful outcome. "I had given myself the time to seriously ponder the situation we find ourselves in. Call it cold feet, but achievements are better enjoyed while still alive. Using this Christmas as a period of forgiveness and inner thought, I prayed to God after celebrating with my family that peace would prevail. I had welcomed compromise and tolerance, settlement not disruption, looking for any lasting hope for peace in our time. Truly I prayed to the Lord that this time next Christmas I would once again bring my family to our isolated estate near the lake my great great grandfather first used as his retreat. I look forward even now to teaching my grandson how to ice fish, just as my grandfather taught me before. Now I don't know if we'll be able to visit our retreat next year. My worst fear is that this was the last time I would ever gaze upon that lake ever again..."

In the weeks following the failure to negotiate any proper compromises with Imperial Authorities, peace and sorrow were swiftly replaced with war and rage. Count Braune dispatched letters to his inner circle as well as those whom were newer to the cause. Using coded language, the letters spoke of gettogethers on certain dates, with the last date dictating "early May once the weather improves." January, February, and even early March were spent on secretive meetings, recruiting last-minute allies, and preparing for the set timeframe Count Braune and his inner circle agreed would be the most ideal time for war. Although some letters and notes are preserved to this day, many of the secret meetings held by Count Braune and his allies remain a secret. However, the clearest picture modern historians have are the notes taken by Florian Valentin Eckstein. Eckstein, one of Count Braune's conspirers outside the Count's inner circle but still within the northwestern region, was a baron about three hundred kilometers south of Braune's County. In his recovered journel, a number of pages illistrate maps depicting plans of attack for the northwestern campaigns as well as notes to go along with them. "The Count's centralized forces to the north will splinter into their respective directions... Southern army will also splinter as the Count expects the Barony, along with any recruits, to splinter to face the eastern corridor and western pass. Converge at Billerei?"

May 3rd, 1891, Count Braune and his inner circle made their first overt moves of the rebellion by dispatching their covert forces on missions of great importance. The weather had warmed up with any snowfall leftover quickly melting. Predictions made earlier in the month estimated that late winter had finally ended and early spring had arrived much earlier this year than previously thought. Given the scenario they now faced, Count Braune ordered his allies to ready by the 20th, stating now was the time for action.

War

Northern Theater

Central Theater

Southern Theater

Insurrectionist Defeat

Aftermath

Notes

- ↑ Simply referred to as the "Nobleman Insurrectionists," these nobles would go on to declare the creation of their own nation which would be named after Count Ortwin Baldo Braune's capital city.

- ↑ According to the Armed Forces Ministry (previously known as the War Ministry), approximately 4 million soldiers were serving the Empire during the 1891 Nobleman Insurrection. It is said that the Imperial Army fielded approximately 150 to 200 Infantry Divisions - or 45 Corps - between the years 1880 and 1899, totaling between 1.8 million and 2.4 million soldiers. The remaining two or more million servicemen are said to have been from other branches of the TECT Armed Forces or militia who temporarily fell into Imperial command during wartime. Corresponding figures from the Imperial War Museum in Reichsstadt contradict the Ministry's figures given that Imperial Divisions could vary between ten and twelve thousand men during this period, however they do indicating approximately 32 Divisions (or 384,000 men) saw action during the war along with several affiliated militia units. This would mean that Imperial units not only outgunned their counterparts but also outmanned the typical Rebel Division by one-to-three thousand men.

- ↑ While figures indicating how many rebels took up arms against the Empire are scarce (for many reasons), the Imperial War Museum in Reichsstadt approximates between 180,000 to 240,000 men took up arms at the behest of their rebelling lords. This number was calculated by using the reported size of participating rebel nobleman armies while accounting for both desertions and volunteers throughout the conflict. Recruitment and payment slips have also been used to gauge how many volunteers/soldiers were retained by Nobleman during the war. Given that Rebel Divisions were often nine-to-ten thousand men strong, and units often utilized older equipment leftover from Imperial use, the average Rebel Division was not only outgunned but also outnumbered by one-to-three full battalions.

- ↑ According to both the Imperial Armed Forces Ministry and the Imperial War Museum in Reichsstadt, the Empire suffered between 18,000 and 20,000 casualties during the 1891 Nobleman insurrection. Most losses are attributed to † or (DOW), but other reported causes include weather and disease. The current reported figure was obtained primarily through medical bill slips and burial slips issued by the Imperial Government.

- ↑ According to the Imperial War Museum in Reichsstadt, Rebel forces suffered significantly higher casualties throughout the war. While Imperial forces are calculated to have lost roughly 5% of their fighting power sent into battle, the Rebels are calculated to have lost approximately over 20% by time the war ended. Some uncorroborated statistics say Rebel forces lost close to 40% of their fighting power, or nearly 100,000 men, by time the war ended. Most losses are attributed to † or (DOW), but other reported causes include weather and mistreatment while imprisoned (Imperials executing prisoners was a regular occurrence). Reported figures were calculated based on counted dead, burial slips, and the medical bills survivors were forced to pay.

- ↑ Conflicts of military nature were partially permitted during this time in the Empire. Although it was taboo for the first thousand years of the Empire's history, gradual internal rivalry and conflicts would eventually force the hand of Imperial Authorities to permit limited conflicts so long as combatants refrained from pillaging or scorched-earth behaviors. These wars would eventually become known as "UnerheblichKrieg," or "Irrelevant Wars." UnerheblichKrieg with the Empire or its protected entities (such as Royalty) was strictly forbidden by law at the time and was considered not only treason but rebellion.

- ↑ Duke Schultheiss, for his numerous crimes on top of leading the insurrection against the Empire, was ordered by the Emperor to be publicly executed on March 13th, 1504 by public hanging. Furthermore, his wife, his children (even his youngest who had barely turned five years old), and extended family were also executed in private ceremonies. Emperor Jochim Reiher Walherich ordered the Schultheiss' personal assets be used to compensate Imperial soldiers, their families, and civilians whom lost property, limb, or loved ones during the war. As for the realm itself, the Duchy was officially dissolved on April 3rd, 1504 as part of Emperor Jochim's reforms. It was replaced by with Prince Hartwin's "Walherich Principality" the following week. Any remaining Duchy assets were ordered to be transferred in ownership to Prince Hartwin Theudoricus Walherich.

- ↑ Prince Hartwin Theudoricus Walherich death ended an era in the Forelis Province. Upon death, as was the original Decree set in place by his father, Emperor Jochim, the Principality was dissolved in 1546. Wernher Gisbert Rothenberg, a Count trusted and vetted by the Prince, had been selected to become the Province's first governing Duke.