Cartulia

Holy Empire of Cartulia Despotismo de Cartulia استبداد كارتوليا | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Anorfod." "Immortality." | |

| Anthem: "Danza de los Iblesi" "Dance of the Iblesians"[1] | |

Map of Cartulia. | |

| Capital | Castillo Alcázarra |

| Largest city | Alcázarra Principal |

| Official languages | Iblesian |

| Recognised national languages | Xedan |

| Ethnic groups | 97% Iblesi Dawi, 3% Other |

| Demonym(s) | Cartulian |

| Government | Absolute Monarchy |

• Déspota Tyrant | Rocinante II |

• Gran Príncipe Grand Prince | Juan-Carlos Rocinantez d'Ladron |

• Ruling House | House d'Ladron |

| Independent (Sovereign) | |

• Juramentos de los Thurha | 1st Primeron 1 ICC |

• Juramentos de Alavarro | 15th Terceron 1 ICC |

• Sumisión de los Príncipes | 12th Cuarton 4 ICC |

• Libro de Leyes | Ongoing |

| Area | |

• | 308,011 km2 (118,924 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 5.2 million |

• Density | 16.9/km2 (43.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | estimate |

• Total | 3,770,000,000 Sigils |

• Per capita | 725 Sigils |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Total | 377,000,000 Escudos (72.5 Escudos) |

| Currency | Escudo (E) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

The Holy Empire of Cartulia (Iblesian: Despotismo de Cartulia, استبداد كارتوليا), more commonly shortened to Cartulia, is a Dawi nation located in southern continental Bezek. Cartulia shares a land border with the Human nation of Ras Vertaz to the west, and the Human nation of Olivel to the east. Mainland Cartulia is located on the island of Iblesia a short distance off the southern coast of Bezek, however the majority of the nation's land area is located on mainland Bezek to the north. The border with Ras Vertaz is defined by the line of the Palencaea River while the far border with Olivel is delineated by the Sadrano Ridge. The Holy Empire is an absolute monarchy with its capital city, Castillo Alcázarra, located on the island of Iblesia; Castillo Alcázarra is mostly a subterranean city occupying the majority of the island. The majority of Cartulia's urban centres can be found underground, with the exception of harbours and ports which tend to be built into sea cliffs and havens to take advantage of the natural terrain. Cartulia has a population of about 5.2 million people, the majority of whom are Dawi.

Cartulia has been inhabited by Dawi for an unknown period of time; it is known that they were already present at the beginning of the First Era XSC because written language was adopted by the Dawi quite early on and much of this original writing was carved in stone. Cartulian historians from the Academia Real de Historiadores in Alcázarra Principal succeeded in deciphering the earliest known Dawi script found in modern day Cartulia, known as the Iblesian Progenitor Script two hundred years ago in 622 ICC which enabled them to read historic accounts of the Dawi inhabitants. Known Cartulian history has it that the Dawi were divided into Thurhata, petty kingdoms ruled over by a series of powerful clan. Though the petty kingdoms were separate political entities the Dawi of the area are believed to have been part of a larger cultural group which formed the basis for the modern Iblesian culture and race. Around 900 years ago the Thurh (lit. King) of Iblesia, Corto I, began the process of actively uniting the Iblesian Dawi and 822 years ago in 1 ICC (or 202 3e XOC, 620 XSC) the process was completed with the Juramentos de los Thurha. Cartulia has been ruled as a single nation since that time under a system of absolute monarchy.

The Cartulian monarchy operates according to the dictates of the Juramentos de Alavarro in 1 ICC; the original document remains, cast in bronze, and set down the powers and rights of the monarch, as well as the laws of succession. The Juramentos de Alavarro are named after Corto I's heir Alavarro Cortez d'Ladron who agreed to uphold the agreements made during the Juramentos de los Thurha, thus ensuring his succession and the continuance of Cartulia as a united nation. The basis of the Cartulian legal system is drawn from the pre-unification laws of the Thurhata of Iblesia and was codified in 7 ICC with the creation of the Libro de Leyes (lit.: Book of Laws), this occurred during the reign of Alavarro I better known as Alavarro Legislador in Iblesian, or Alalvarro Lawmaker in Xedan. Each clan and city holds its own Book of Laws into which all legal decisions are written, every five years all of these books are brought to the capital and collated; new laws are thus made based upon the decisions made in the preceding five years. The core Book of Laws remains and only the monarch or a majority of the Judiciar can overturn existing laws. Cartulia's government is run and facilitated by a vast bureaucratic machine known as the Servicio Real (lit.: Royal Service), a kind of civil service which has functionaries present in every settlement overseeing everything from law enforcement to taxation.

Cartulia is a reasonably wealthy nation. Its economy focuses on the Dawi tradition of stone and metal working as well as the extraction of minerals from the earth, however unlike many Dawi nations it also has a strong agricultural base above ground to support its subterranean enterprises. Cartulia operates an open economy in which serfdom has been abolished in favour of free individual enterprise; this has led to the creation of a guild and company system. Taxes are paid to the local Thurh who in turn pays taxes to the reigning Déspota. The free enterprise and capitalist nature of the Cartulian economy, which focuses upon a meritocratic system of gaining wealth, has resulted in the development of a fluid class system and what can be described as a large Middle Class by comparison to many other nations. The national budget is managed by the Banca Real (lit.: Royal Bank) which is an organisation within the Royal Service. Meanwhile the nation's currency is issues, regulated, and maintained by the Menta Real (lit.: Royal Mint), another arm of the Royal Service, which is held in high esteem.

The army and navy of Cartulia are highly organised and run directly by the state; clans provide a tithe of youths to enter the military and Cartulian soldiers and seamen are trained in their craft from the age of six. The core of the Cartulian armed forces are the Marinos Real (lit.: Royal Marines) which serves as both naval ground forces and the army itself. The military is a meritocratic organisation which swears direct allegiance to the Déspota and is led by officers trained and appointed by a panel of retired officers and generals under the direction of the Royal Service.

Etymology & Terminology

The name Cartulia is derived from the mythological Iblesian hero Cartu Valdez d'Lus who overthrew the pre-Iblesian Idaasi civilisation which had enslaved the Dawi of the area. In modern Iblesian Cartulia has no direct translation however in Early Iblesian it literally meant "Liberated by Cartu". Even though the post-Idaasi Dawi did not unify under Cartu's reign they used his name to refer collectively to the lands they now inhabited and ruled. Due to the continued veneration of Cartu d'Lus at the time of Corto I's unification of the territories neither Corto nor his nation's name superseded that of Cartu.

Known in Xedan as 'The Holy Empire of Cartulia' this is in fact only a close approximation to the actual meaning of the nation's Iblesian title of Déspota. There is no direct translation of the term Déspotismo into Xedan, though the title of Déspota roughly means Despot in most interpretations; however by nature the Déspota is also a figure of religious significance and veneration and is as much a spiritual leader as a political or secular one. Some scholars argue that a more appropriate title for the Déspota would be Emperor since they rule over multiple kingdoms and kings, however the Déspota is a more direct and centralised absolute monarch than an Emperor would typically be and the Cartulian kings are more akin to senior nobility in terms of their status and power.

The full Iblesian name for Cartulia is Déspotismo de Cartulia, however it is more commonly referred to abroad by the name The Despotism of Cartulia and only occasionally as the Holy Empire.

History

The lands of Cartulia have been continuously inhabited throughout recorded history, with early Dawi records indicating that for at least three centuries prior to the creation of writing an organised civilisation known as the Idaasi ruled over the territory. It is unknown what species the Idaasi were as they were wiped out by the Dawi at some time prior to the invention of writing and written records, however the Idaasi were powerful enough according to Iblesian mythology to enslave the Dawi of the region until the rise of Cartu Valdez d'Lus and his rebellion. The few remaining Idaasi ruins are enigmatic locations that hint at an incredibly advanced society, a prime example is the lone mountain at the centre of Iblesia which forms the core of the city of Alcázarra Principal which was raised through the use of powerful magic by the Idaasi for some unknown reason. Centuries of Dawi habitation of the mountain have obliterated the majority of the Idaasi structures in and around the capital city, however on the Bezek mainland near the coastal city of Puerto Alcázarra the ruins of an Idaasi city known as Nekhepolitur remain more or less untouched and are a site of superstitious dread and taboo. Cartu d'Lus' rebellion against the Idaasi and the subsequent obliteration of the Idaasi civilisation in its entirety are the subject of numerous ancient myths and legends, and though clear written records carved in stone or cast in metal do remain dating back over one thousand four hundred years, Cartulia scholars remain divided as to whether Cartu d'Lus and his accomplishments are a matter of fact of historic fiction.

Thurhata (c. 320 BIC - 74 BIC)

According to the commonly accepted history of the Iblesian Dawi of Cartulia the Greater Clans (each lead by a Thurh) separated and each founded their own independent petty kingdoms; collectively these kingdoms were referred to as the Thurhata and shared the common Iblesian Dawi culture. Though each of the Thurhata were sovereign and ruled by their own King the bonds of Cartu d'Lus' legendary rebellion and the shared Iblesian Dawi culture meant that the Thurhata were akin to a confederation which could easily unite in response to external crisis. An attempted seaborne invasion in 127 BIC by Adaasi raiders was met with the united front of all of the Thurhata even though only the coastal regions of Cartulia were affected by the raids and invasions, and from 123 BIC the patrolling of Cartulian waters for pirates and raiders became a joint responsibility. By 80 BIC, shortly before Corto I began unifying Cartulia, all of the smaller Thurhata had been absorbed into one or other of the larger Thurhata, leaving only five. The Thurhate of Iblesia established its position as the pre-eminent power among the Thurhata in 74 BIC when the thrones of Cejana and Zidacca were inherited by members of House d'Ladron, the ruling House of Iblesia, thus making them tributaries of Corto I.

Unification (74 BIC - 1 BIC)

Corto I used his position as the overlord of three out of the five Thurhata to leverage hegemony over the remaining two and in all but name the entirety of modern day Cartulia was under his dominion by 62 BIC. Initially the territories of Cartulia were not unified as a single state but rather as a series of states which owed tribute and fealty to the king of Iblesia, records on the subject are unclear as to whether or not Corto I intended for this to be the case on a permanent basis, however in 24 BIC a rebellion in Zidacca and Badajara which intended to restore the power and end the system of fealty to Iblesia spurred military action. For the following twenty four years, until the defeat of Zidacca and Badajara's forces in 1 BIC, Corto I waged a ruthless military campaign characterised by rapid manoeuvre and the practice of decimation of captured enemy soldiers. At the turn of the year following the surrender of the rebellion's leaders Corto I proclaimed the Despotisma and had himself crowned Déspota, forcing the leaders of the Greater Clans to accept the Oaths of the Bruinkanz.

During this time the military forces of the Iblesian Dawi were largely part-time, with only a limited warrior class in the form of personal bodyguards. Corto set himself apart by establishing a large professional fighting force was standardised training focused upon the idea of disciplined formation fighting. The bulk of Corto's army were spearmen wearing bronze and leather armour; what made these spearmen particularly effective however was that they carried a plata almost as tall as they were and were given a bronze or iron kukri as a secondary armament. Intended to fight in close formation and trained to form both square and rounded formations depending upon the conditions, these spearmen were versatile and man for man far more effective than the less disciplined troops they faced. Corto was not content to rely upon heavy spear infantry alone however, and employed a number of more specialised troops including skirmishers and archers as well as a small cadre of elite cavalry mounted on great mastiffs. Most notable among Corto's forces though were his royal guard, led by Kira Miri Drohz, who were each gifted uniquely engraved plate armour and a two handed axe; according to contemporary accounts no rebel formation or force could withstand a heavy infantry charge from Corto's royal guard.

Post-Unification (1 ICC - 22 ICC)

Following the unification of Cartulia by Corto I the process of consolidated and solidifying the unity of the nation was begun. Corto I began with the creation of the Royal Service in 2 ICC and left its formalisation and management to his trusted advisor Jura Ibrahiminez d'Guis while he proceeded to make a tour around the newly unified nation of Cartulia with the army he had used to crush the rebellions in Zidacca and Badajara; the progress was slow because the army was required to lay a basic road everywhere it went to connect the overland settlements of the Bezek mainland to one another; they also established fortifications near each major hold's surface entrance which were manned by troops taken from the forces he brought with him. Additionally everywhere Corto I went he left a cadre of bureaucrats to ensure that his will was carried out. Contemporary historians view the reign of Corto I as one of violence and oppression and though he unified the country it is the prevailing view that he was a bloodthirsty tyrant who brutally crushed any hint of dissent or rebellion no matter how trivial; at the time however, perhaps as a form of early propaganda, the intelligentsia and academic classes portrayed Corto I as a strategic genius.

Oaths of Succession (1 ICC)

One of the terms by which the Thurha had agreed to the Oaths which had ended the rebellion and unified Cartulia was that Corto I establish a clear line of succession and guaranteed the continuity of his line's rule. Corto had many children by multiple wives and tradition held that the eldest child of each of a man's wives inherited an equal portion of their father's estate upon his death; this however was an unacceptable arrangement for the Thurha and for the Judiciar who sought to prevent further bloodshed and war between the Iblesian Dawi. Thus, three months after proclaiming the Despotismo Corto instructed Jura Ibrahiminez d'Guis, the head of the Royal Service, to form a set of oaths to be sworn by Alavarro, the most promising of his sons and a further set of oaths to be sworn by his remaining children, to ensure a smooth succession. On 15th Turceron 1 ICC Alavarro made the Juramentos de Alavarro, securing his place as the sole heir to the throne. Those among Corto's remaining children who accepted Alavarro as their next Déspota made the Sumisión de los Príncipes in 4 ICC, formalising their places in the line of succession. Several of the Déspota's children refused to swear the Submission were put to death along with their mothers, setting a precedent which would last until 444 ICC.

Reign of Alavarro I (5 ICC - 23 ICC)

Alavarro I assumed the throne in 5 ICC upon the death of his father. Unlike his father who was a warrior by nature Alavarro was far more interested in the strategy on politics of rule. Unsatisfied with the disparate and ill defined nature of law in Cartulia Alavarro began the process of forging a unified and codified system of laws, starting with the creation of the Libro de Leyes (lit.: Book of Laws). Alavarri placed the responsibility of administering justice to the Judiciar, a council of elders from all of the Greater Clans. A copy of the Book of Laws was sent to each major settlement and given into the care of the local Thurh. The focus of Alavarro I's rule was the formalisation and standardisation of law throughout Cartulia, as well as the establishment of the rights of his people. One significant issue was the enforcement of serfdom among the surface dwelling communities of Dawi who tended the fields; up to this point serfdom had not been universal but it was made so by Alavarro I.

Much of Alavarro I's reign was defined by brutality and violence. The Bazh had inherited his father's fervent desire to unite Cartulia and maintain the nation, but lacked his father's principles and scruples, in addition the new Bazh was considered to be paranoid and given to bouts of hysteria. This extreme paranoia was displayed through the constant arrests for treason that defined his reign and though the accused always received a trial under the dictates of the laws Alavarro had established more often than not the evidence provided was insubstantial or based on hearsay. During his eighteen year reign Alavarro I created and fostered an atmosphere of terror that no-one dared to openly resist due to the loyalty of his troops and the Royal Service to him.

In 23 ICC Alavarro I died under mysterious circumstances. I was believed at the time that he had been assassinated at the behest of members of the Thurhada in order to end the terror and progress to mare stable regime; however more recent research into previously lost diaries and records indicates that he was in fact murdered by his daughter and heir Caira in order to prevent him from destroying their line's hold on the Cartulian throne.

Early Despotismo Period (23 ICC - 320 ICC)

The Early Despotismo Period began in 23 ICC with the untimely death of Alavarro I and the succession of his eldest daughter Caira I. The period was largely defined by the development of Cartulia from a pseudo-feudal society into a centralised and habitually united nation, and is considered to have come to an end in 320 ICC with the rise of the Cartulian Nationalist and Leveller movements.

Reign of Caira I

The central policy during Caira I's reign was that of converting the institutions her grandfather had created in order to ensure his hegemony over Cartulia's clans and Thurhata into centralised national institutions. In 29 ICC she instructed the Royal Service to reform her father's army into the Marinos Real (lit.: Royal Marines), expanding its recruitment pool significantly by requiring that each clan provide an annual tithe of six year old children to be sent to Alcázarra Principal to begin their training. Caira's military reforms did not end with recruitment; she further introduced the concept of mass standardisation of equipment and the specialisation of troops within a tight organisational structure based around one hundred man formations known as Ciento. While her reforms did not bring an end to the system of political appointments to high military command, or nepotism with regards to officer candidacy, it did create the precedent and principle by which a meritocratic system could be introduced later. Caira would continue to focus on military reforms throughout her reign, though the only combat her reformed army would see would come in the form of a series of insurrections and coastal raids by pirates. Caira's reign came to an end in 121 ICC with her death at the age of one hundred and thirteen, and she was succeeded by her son Alavarro II, and was enshrined as Caira Espadacante (lit.: Caira Swordmaker).

Reign of Alavarro II

Alavarro II shared similar motivations to his mother and was fascinated by military matters; however unlike his mother who had inherited a nation with room for reform and a need to develop, Alavarro had inherited a disciplined and effective army in the form of the Royal Marines established by his mother. Instead Alavarro set his eyes upon the navy; though the Royal Marines were trained and intended to serve at sea as well as on land, the organisation behind the ships that actually carried them was far less effective or well conceived. Corto I had only needed to use his ships as a means of transporting troops along the coastline, most of the fighting during the unification had taken place inland and as a result he had seen no need to further organise a naval force during the unification. Prior to the reforms of Alavarro II the navy was practically non-existent with civilian and merchant vessels being conscripted during times of conflict; a system which though cheap, was not particularly effective and left Cartulia vulnerable to piracy and coastal raiders. Alavarro commissioned the construction of the nation's first dedicated military shipyard in Puerto Alcázarra in 122 ICC and construction was completed in 129 ICC; the shipyard was massive, carved into the rock of the sea cliffs north of the city proper and could be used to construct four ships at a time. Under Alavarro's direction the Royal Service established departments responsible for the management of the marines and the navy; these would include institutions with the goal of equipping, supplying, and maintaining soldiers and ships.

The reign of Alavarro II also saw the rapid growth of trade as well as the beginning of international trade overseas for Cartulia itself. The Greater Clans could afford to invest in trading expeditions that brought back new materials and ideas; Alavarro himself however was only passably interested in economic concerns and was content to allow the situation to manage itself. As long as the Greater Clans continued to pay taxes he did not seem to mind where they got their coin from. The governmental indifference to the growth of trade left it in many places totally unregulated; on the one hand this had the benefit of causing banking to take hold as well as modern mercantile practices, but on the other without regulation wealth disparity was extreme and a system of indentured servitude evolved. While income inequality was nothing new at this time poverty became rampant and the nation faced a series of food shortages due to wider mismanagement. At the time of Alavarro II's death in 158 ICC the nation was facing growing food shortages and a rising infant mortality rate.

Reign of Miguel-Carlos I

Alavarro II was succeeded by his son Miguel-Carlos I in 158 ICC. Miguel-Carlos I was the first of the Cartulian Déspotas to have been born heir to the throne and was the first who by no means had to worry about preserving his rule against internal threats. Sometimes known as Miguel-Carlos Suficiente (lit.: Miguel-Carlos the Complacent), he did little to help restore his nation's former economic strength. The reign of Miguel-Carlos I was marked by a period of general malaise among the upper classes and the suffering of the poor as a result of the rampant growth of exploitative capitalism; the result of this was an overall contraction of the economy and weakening of the nation's prestige. However culturally the nation flourished and entered a golden age of art and literature as Miguel-Carlos and other members of the elite began to commission works of art and writing. Notably various methods of acid etching were first discovered and employed in Cartulia during the later years of his reign, allowing the more effective practice of creating books and texts with pages made from copper and bronze.

During the reign of Miguel-Carlos I Iblesian Dawi artistry developed and examples of statuary and earthen goods from his reign are now highly sought after status symbols. Prior to the reign of Miguel-Carlos a great deal of the artwork created in Cartulia was rendered in stone, with only the very wealthy commissioning painted works, the primary focus was ensuring that the art would last, a view which declined over time as less permanent modes of artwork which provided more versatility became readily available. Paintings started to be worked onto canvas and boards in place of walls or stone tablets and more and more portable artwork was created, rather than works integral to a building. A transition was made away from the ancient Dawi tradition of carving their artworks on a grand scale.

Reign of Miguel-Carlos II

Miguel-Carlos II began his reign in 204 ICC upon his father's death from tuberculosis. Miguel-Carlos II was a much more austere character than his father who valued simple pleasures and much of the works of art his father had accumulated were thus sold off in order to fund national infrastructural projects. A highly religious man Miguel-Carlos II proceeded with a series of policies aimed at improving the lot of the lower classes in society, however he took a very high minded approach to the task. Believing that the development of new roads both above and below ground would be critical he set about on a massive program of road building, using his military as a workforce. He also introduced foreign ideas such as water wheels and windmills which markedly increased agricultural output. Miguel-Carlos II further wrote a number of texts regarding good governance, the most successful of which has been taught to all of his descendants to this day. Despite the developments spurred on by Miguel-Carlos II standard of living improvements for the poorest in Cartulia did not occur leading to widespread resentment amongst the populace; several attempts to end serfdom and spur on further social reform were made however Miguel-Carlos II firmly opposed such radical policies.

Reign of Rocinante I

Miguel-Carlos II was succeeded by his daughter Rocinante I in 266 ICC upon her father's natural death. She inherited a strong and powerful central government and a well developed national infrastructure; however she also inherited the problems that her father's reign had created. The system of serfdom was starting to strangle the economy and hinder the nation's development, in many cases children were effectively being sold into slavery, and the country struggled to develop a large and diverse middle class as a result. True craftsmen and artisans were becoming increasingly rare and the nation started to suffer from a significant brain drain as the educated and skilled sought better opportunities elsewhere. As a means of countering these issues Rocinante I established a number of institutions including Royal Academies, and Royal Societies to support and promote the evolving Iblesian Enlightenment ideas, however like her father she refused vehemently to concede to demands to end serfdom outright, instead introducing reforms allowing serfs to buy their way out of bondage.

During Rocinante I's reign the twin ideologies of Cartulian Nationalism and the Levellers developed and grew in popularity, culminating in the Loyal Revolution of 311 ICC during which a coalition of serfs led and supported by merchants and tradesmen started to occupy local counting houses and Royal Service offices, refusing to pay taxes or allow the normal functions of government. The Loyal Revolution would last for six years while the Marinos Real struggled to put it down. Several units within the armed forces and within local militia and law enforcement that were sent to deal with the revolutionaries actually defected once they discovered the nature of the movement's demands. Ultimately the Loyal Revolution ended in 317 ICC with the Counting House Siege in Puerto Alcázarra, during which the movement was broken and forced to capitulate after Rocinante I ordered her Royal Guard to storm the building. For the remaining two years of her reign Rocinante I attempted, with limited success, to round up the ringleaders behind the revolution, until her death in 319 ICC. She was succeeded by her son Juan-Carlos I who a year later in 320 ICC bowed to widespread pressure and abolished serfdom.

High Despotismo Period (321 ICC - 644 ICC)

The High Despotismo Period began in 321 ICC following the 320 ICC abolishing of serfdom. It is the abolition of serfdom, and not the succession of Juan-Carlos I which defines the beginning of this period in Cartulia's history. The period was one of significant social, economic, and political change, which would see the traditional economic system give way to one of Guilds and Companies; the growth in personal liberties and the beginnings of new class system all took place during the High Despotismo Period. These changes however came during a golden age for the unquestioned power of the Déspota; the growing Iblesian Enlightenment movement encouraged the evolution of an ideology of enlightened despotism among successive Enlightened Déspotas and their close advisors. The precise date of the end of the High Despotismo Period is debated, however the most widely accepted year is 644 ICC when legal concepts such as habeas corpus, jury trials, and the presumption of innocence were formally codified.

Reign of Juan-Carlos I & the Cartulian Civil War

Juan-Carlos I had inherited a strong military position; his mother had successfully defeated the armed uprising, the Loyal Rebellion, which had tried to force her to abolish serfdom, his armies were motivated, well supplied, and prepared to put down another rebellion if necessary. However Juan-Carlos I was not a warrior; as a child he had excelled as a scholar and artist, and had never built up any sort of reputation except for his intellect; as a result he was seen by many as weak, a potentially impotent monarch. The head of his military forces, Enrico d'Vaasco, did not believe that Juan-Carlos I had the stomach for a fight and urged him to avoid further conflicts or potential rebellions. Over the course of the first year of his reign the peaceful demands for reform increased as it became clear that Juan-Carlos was not going to defy the advice of his court, and in 320 ICC he formalised the abolition of serfdom without a fight. In the short term the decision was a poor one, the nobility were disgusted and many withdrew from the court in protest; however Juan-Carlos' most senior advisors, as well as his Servicio Real remained loyal - so too did Enrico d'Vaasco and the Marinos Real.

In 323 ICC the Thurhas of Badajara, Zarajoz, and Cejana sent a joint ultimatum to Juan-Carlos demanding that he reinstate serfdom and pay restitution for the financial losses they had suffered as a result of his decision. In the face of the threat of open revolt however Juan-Carlos defied expectations and rejected the ultimatum out of hand, ordering the mobilisation of the Marinos Real and officially stripping the Thurhas and their supporters of their lands and titles. The three Thurhas formed a coalition and rebelled, raising their own local troops, relying upon clan allegiances and old debts to raise a substantial force. With military forces mobilising on both sides the Thurha of Zidacca proclaimed his loyalty to the throne, abandoning his own protests against the abolition of serfdom in the process and leaving the nation divided. Geographically the loyalist forces held a smaller proportion of the nation, however Iblesia and Zidacca were the two wealthiest and most populous of the Despotismo's Thurhatas, and Juan-Carlos had a disciplined, loyal, and highly motivated military behind him.

The first battle of the Cartulian Civil War occurred late in 323 ICC outside the town of Guadevilla, on the border between Zidacca and Zarajoz and resulted in a rebel victory. The loyalist forces, led by the local Baronesa, Lucia Gomez d'Guadevilla, were a mixed militia force reinforced by a contingent from the Puerto Zidacca City Watch; the local Marinos Real garrison had been redeployed following threats from the north leaving the loyalists with no full time soldiers and a force of just 400 infantry. The rebel forces, led by Hernan Enriquez Conte d'Virahua, numbered around 600 and consisted of a similar combination of militia and law enforcement forces, supported by fifty soldiers from the Thurha of Zarajoz's household guard. The battle lasted for a little less than six hours and resulted in approximately 300 casualties before the Baronesa d'Guadevilla was forced to retreat. A series of similar small scale battles along the borders of Zidacca characterised the early stages of the war; within the first three month the loyalists had lost eight out of eleven battles leaving the rebel leadership confident that they could remove Zidacca from the war before the Marinos Real could be brought to bear.

In early 324 ICC the fortunes of the loyalist forces in the civil war turned; after having a communication smuggled through siege lines to the commander of the Marinos Real garrison at Escon in Cejana, a successful breakout action was fought defeating the besieging forces. The troops from Eson marched south to the coast where they were resupplied and reinforced and the garrison commander, Coronel Luca Sucozu, was ordered to carry out a cavalgada throughout southern Cejana which culminated in the sack of Puerto Cejana in early 325 ICC. Sucozu's cavalgada severely weakened Cejana's military capability and the credibility of its leaders; Sucozu had be covertly spreading propaganda regarding the abolition of serfdom and what it meant to the serfs themselves and by the end of 325 ICC the majority of Cejana was in open revolt against the rebel forces. Coronel Sucozu finally committed his force, one thousand Marinos Real, bolstered by an irregular force of approximately three thousand Cejano rebels, to an open battle against the Thurha of Cejana's forces. At the Battle of Altevera on 12th Secundo 326 ICC the loyalist forces dealt a crushing defeat to a rebel force of around three thousand soldiers. The Thurha of Cejana, Umberto Ibrahim d'Cejana, was killed in the fighting and his heir, Roserta Rebecca d'Cejana was captured and formally surrendered.

The Thurha of Zidacca began his own campaign in 324 ICC, determined to avenge the defeat of the Baronesa de Guadevilla, he marched on Puerto Zarajoz with a force of four hundred Marinos Real, supported by his own household troops numbering one thousand, and a militia force of a further thousand soldiers. The Siege of Puerto Zarajoz lasted for a little over four months and proved to be a costly victory for Zidacca who lost many of his militia force to disease; the resulting sack of Puerto Zarajoz was more akin to a massacre as the enraged Zidaccan troops put the city to the sword. The Thurha of Zidacca was censured for this action by Juan-Carlos I, but beyond a reprimand suffered no punishment. The sacking and subsequent occupation of Puerto Zarajoz saw the defeat of the last of the Thurha of Zarajoz's professional soldiery and forced the Thurha and his remaining forces to retreat east. However as 325 ICC began advances from Badajara into Zidacca forced the Zidaccan forces to retreat from Zarajoz, surrendering all but Puerto Zarajoz and Castillo Zarajoz in the process.

By late 326 ICC the Marinos Real had advanced through Cejana in the south and Zidacca in the north; of the rebel Thurhatas only Badajara remained in any position of strength; Cejana was overrun and its people had rebelled, joining the loyalist side, while Zarajoz had lost control of its main population and economic centres. It was only the geographical size of Badajara which hindered any potential invasion of the territory. Nevertheless Juan-Carlos I could not afford to lose and though he was not a military man himself he led his forces personally on the march to the city of Badajara. Juan-Carlos I's march cut through Zarajoz capturing the last of the Thurhata's coastal settlements and brushing aside what remained of the Zarajoz army; then it wheeled around the city of Badajara and struck Castillo Badajara to the north. Two weeks of constant bombardment laid waste to Castillo Badajara, the most fortified location in the territory, and when Juan-Carlos finally ordered the ground assault their was little left for the defenders to hold but charred remains and rubble. The crushing defeat, and subsequent utter destruction, at Castillo Badajara forced the last remaining rebel Thurha to the negotiating table. Initially, on the basis that his army remained in the field and ready to repel the loyalist forces, the Thurha, Domingo Juara d'Badajara tried to negotiate terms by which serfdom could be retained in Badajara - Juan-Carlos was in no mood to compromise however and ultimately the Thurha d'Badajara surrendered with the only terms being that he and his family be allowed to flee into exile.

With three out of the nation's five Thurhas having been deposed in the civil war Juan-Carlos set about restructuring how the nation was run. The Thurhatas would now be administrative divisions with Iblesia and Badajara being split into two provinces. The rulers of the provinces would continue to be called Thurhas, and the positions would be hereditary, however Juan-Carlos stripped the existing ruling families of Badajara, Zarajoz, and Cejana of their titles and status, elevating new, more loyal clans to replace them. One of the main beneficiaries of these changes was Capitán General Enrico d'Vaasco, who for his loyal service was made Thurha of Zarajoz. Other notable beneficiaries were Coronel Sucozu who became Thurha of Cejana, and the Baronesa de Guadevilla who was given Badajara Occidental.

The end of the civil war not only signalled the final end to serfdom in Cartulia, it also signalled a significant change in how the country was organised. The Thurhas would remain, and the position would be hereditary, but much of their power was stripped away and transferred to the Royal Service; the aristocracy as a whole was weakened and the war had opened up new avenues of opportunity for the lower classes. In place of the old system a new one was established, the Guilds system. Under the reforms Juan-Carlos I enacted following the civil war hundreds of guilds were established covering all manner of trades and professions and a system of standardised guild education and formal charters replaced the old feudal economy. The transition was not an easy one; the plan was a long term solution and in the short term massive problems were faced. It would take thirty years for the full benefits of the new economic system to take hold during which time Juan-Carlos I struggled against dissent and second guessing within his court and Royal Service.

Juan-Carlos I was an obsessive ruler. Following the civil war he had taken to studying every aspect of governance as well as a whole host of other subjects such as economics and modern technologies; seeking to use his own absolute power and popularity with his subjects to reform and improve the nation. Although he had been seen as a weak and scholarly ruler prior to the civil war Juan-Carlos succeeded in thoroughly shedding that reputation; contemporary politicians and historians described him as ruthlessly efficient, harsh, but fair. Having begun the process of economic reform he also tackled the issue of law and reformed the nation's legal code by introducing concepts such as stare decisis and legal egalitarianism.

By the time of his death in 402 ICC Juan-Carlos I's vision for Cartulia had largely been realised. His economic reforms had given way to an established status quo and serfdom was a distant memory. The guilds system had created three successive generations of guild trained freemen, proving its potential and setting up a social precedent for upward mobility.

Reign of Alejandro I

Alejandro I ascended to the throne in 402 ICC upon the death of his father. As the eldest of Juan-Carlos I's children Alejandro was already considered to be past his physical prime; he had also spent much of his father's reign living lavishly on the considerable allowance given to him. His reputation among senior advisors to his father, and senior members of the Royal Service, was far from positive and the leaders of the nation's Guilds paid only lip service to his opinions. However Alejandro inherited the throne at the height of the power of the monarchy in Cartulia; the military was utterly loyal to the crown, the general populace transferred their affection for Juan-Carlos to his son, and the nobility remained fearful of what would happen to them should they rebel or challenge Alejandro's rule. The cumulative result of these factors was that no reform was so much as attempted during Alejandro's reign; in lieu of a strong leader with a firm vision the Royal Service operated in a holding pattern, ruthlessly maintaining the status quo until Alejandro was succeeded.

Much of Alejandro I's fourteen year reign was wasted on parties and extravagant spending to build numerous pointless palaces and monuments. Alejandro I rarely put his foot down to ensure that the few decree that he made were actually carried out, however when he did it tended to be over trivial things such as the building of monuments to commemorate his and his ancestors' glory. Alejandro was not however a patron of the arts, while he spent a fortune on ornaments, decorations, and artwork, he lacked taste or any sense of what made good art, judging a piece by its asking price rather than its actual quality. A string of high maintenance and garish palaces, museums, and galleries were the result; poorly made, exorbitantly expensive, and largely filled with poor quality works with inflated value. His lifestyle matched his spending habits, extravagant and excessive, rich foods and an excess of strong drink exacerbated Alejandro's political and economic incompetence by rendering him physically incapable for the final nine years of his reign.

Alejandro I died in 416 ICC and despite his stated desire for a grand state funeral he was hurriedly interred in as simple a sarcophagus as befit a monarch in a small ceremony. Ultimately it was drink which killed Alejandro and he had suffered from severe gout and was morbidly obese; not to mention kidney and liver disease. Alejandro's corpse had to be carefully treated postmortem to prevent it from exploding, and his remains were burned prior to being placed in the sarcophagus in order to ensure that they fit inside.

Reign of Caira II

Caira II succeeded her father in 416 ICC. Her ascension was somewhat unexpected to some as her elder brother Alejandro had been their father's choice of successor; however the young prince who bore his father's name was weak willed and incompetent, and was pressured into abdicating his right to the throne in favour of his sister by the Royal Service in exchange for an annual allowance. Caira II was more like her mother, Alejandro I's second wife, than she was her father. Anna Magdalena d'Vaasco had been a shrewd woman, descended from the famed general and Thurha of Zarajoz Enrico d'Vaasco, she had leveraged her family's prestige as well as her physical beauty to secure her marriage to Alejandro I, despite her private distaste for the man. Caira II had benefited from her mother's tutelage as well as her uncle, the Thurha of Zarajoz, Enrico II Enricez d'Vaasco's support, and was extremely well educated. Upon her coronations comparisons were made between her and her grand-father Juan-Carlos I, in that he too had been considered scholarly and erudite.

Echoing the actions of her ancestor Miguel-Carlos II, Caira II set about liquidating the vast and largely pointless assets accumulated by her father; unlike Miguel-Carlos II however she retained the items of good quality, and became the true patron of the arts that her father had never been. Caira II did away with what she considered by rubbish and mediocrity and set about establishing national galleries and museums that could actually be held up as fine examples of culture. The lingering effects of Alejandro I's brief reign allowed her to sell off vast quantities of substandard art and garish palaces early on, enabling Caira II to streamline the monarchy's assets and build up the funds needed to invest in other projects.

Caira II's biggest contribution was her founding and investment in the Guild of Klytokenes which brought together the various magically gifted and learned Iblesian Dawi who specialised in the magical manipulation of matter for the purposes of construction and fabrication. Klytokenistry was an ancient craft among the Dawi of Cartulia, however it had never had any sort of standard for quality or learning applied to it; indeed it was such an arcane and rare gift that many believed it foolish to try and impose the guild system upon it. Caira II however was herself a Klytokene of modest ability, as well as a student of her forebear Juan-Carlos I, and believed wholeheartedly that Klytokenistry could be organised, standardised, and taught. The Guild was also placed in charge of the Museum of Klytokenistry which housed a comparatively vast collection of magical items and magically manufactures objects that had been accumulated by the Cartulia monarchy; the museum became a hub for the study of Klytokeniery and its collection formed the basis of more modern research into ancient forgotten techniques or principles.

Caira II died in 503 ICC at the age of 134, her longevity credited to her practice of magic, though this was never confirmed. Upon her death she was enshrined as "Caira II el Artesano" (lit.: Caira II, the Artisan).

Reign of Miguel-Carlos III

Miguel-Carlos III was crowned in later 503 ICC and was the youngest of Caira II's children. As had happened with Caira II's accession Miguel-Carlos III was the chosen candidate of the Royal Service, unlike his mother however Miguel-Carlos III was named heir to the throne prior to her death. Miguel-Carlos III was regarded as an austere yet eloquent man who believed in the absolute power of the monarchy in Cartulia and exercised his prerogatives readily to support projects that interested him. Most of the grand projects during Miguel-Carlos III's reign were centred around the development of Iblesia Mejor and Iblesia Menor, in particular the growing city of Alcázarra Principal which lay on the fertile land below the capital; much of the old city and the slums were cleared out and demolished and as his reign continued Miguel-Carlos III's obsession with building a model city grew.

By 534 ICC a combination of Miguel-Carlos III's obsessive development and economic growth led to the vast expansion of Alcázarra Principal in terms of both population and area occupied, indeed the city grew to such an extent that it swallowed nearby settlements such as Puerto Alcázarra and expanded to the gates of Castillo Alcázarra itself. Vast amounts of money from the royal treasury had been spent in concert with Guild investment and contributions, making Alcázarra Principal a modern city which featured a functioning enclosed sewage system and safe water supply capable of maintaining the growing population. In 541 ICC Puerto Alcázarra's Canal Subterraneo was completed at great cost; the canal was carved into the cliff face creating a huge tunnel, large enough to allow the passage of ships; the goal of the project had been to create a fully subterranean harbour further inland, however as the canal project came to a close the royal treasury was exhausted and Miguel-Carlos III's government was unable to secure further loans. The canal itself became a harbour with jetties and landing areas built along the edges.

Although his spending had focused upon infrastructural and economic projects Miguel-Carlos III drained the treasury dry at a pace which could not be sustained, even with the reasonably efficient tax system he had inherited from his predecessors he was not able to raise money as quickly as he spent it. This leaves historians with mixed feelings about Miguel-Carlos III and his reign; apologists pointing out that what he was spending money on benefited the nation, while detractors point out that he spent too much too quickly. The result in this sudden lack of government funding resulted in an early example of an economic bubble bursting; Miguel-Carlos III's projects and funding had enabled the construction and engineering guilds to expand, create new jobs, and generate revenue for themselves thus expanding this sector of the economy; with royal funding for projects suddenly gone the financing needed to sustain their growth simply did not exist leading to unemployment and a devaluation of the construction industry.

Miguel-Carlos III spent the remainder of his reign trying to refill the treasury and generate capital for the nation, however his efforts, combined with the debts he had incurred made progress in this regard slow. Upon his death in 558 ICC he had succeeded in regaining a small reserve of money in the treasury and in ensuring that spending was balanced such that the treasury could pay off the interest on the debts it owed. Overall the nation's economy was strengthened by Miguel-Carlos III's reign, although the construction bubble that he had created and the severe depletion of the nation's treasury would have lingering effects for decades.

Reign of Alavarro III

Alavarro III took the throne in 559 ICC after a brief but peaceful interregnum. His father Miguel-Carlos III had left two conflicting wills declaring two different successors; ultimately the more recent will was enforced allowing Alavarro to take the throne. Alavarro was not the Royal Service's first choice for a successor, however the alternative set out in the earlier will was considered to be a worse possibility and so the government settled. Alavarro III was the son of Miguel-Carlos III's third wife, who was the daughter of a high ranking member of the Guild of Merchants, never expected to succeed his father his education had been left in his mother's hands who expected him to follow in her footsteps and become a chartered merchant; as such Alavarro's education had focused upon accounting, finance, and trade. On paper this education might have seemed ideal for a nation needing to recover financially, however contemporaries of Alavarro in the Royal Service doubted his political and diplomatic capabilities and sought to avoid seeing the country run in the fashion of a merchant enterprise.

The doctrine adopted by Alavarro III from the very beginning of his reign was one of capital generation, however his inexperience at governance and administration made him heavily reliant upon advisors and the Royal Service. Progress on rebuilding the national treasury and remedying the economic bubble created by his father was slow and published documents from Alavarro III's reign plainly show that he chafed at the constant struggle, believing himself to be less competent than he might have been. A general lack of confidence seems to have defined Alavarro III's reign from 566 ICC on and he increasingly leaned on the Royal Service for advice and in some cases instructions on what to do. This indecision exacerbated the growing social problems which had been seeded by his father's economic failings; the populace who were increasingly well educated and aware of current affairs were starting to develop the idea that the nation existed to serve its people and not the other way around. A number of protests took place over the subject of taxation and demands for a more meritocratic society.

In 570 ICC Alavarro III began to reform the economic and tax system, breaking the economic and societal monopolies of the Guilds. Education became a government provision and a right that was unrelated to the Guilds, children could no longer be indentured or form economic contracts, and the Guilds no longer controlled when, where, and under what circumstances, their members could work. Meanwhile the tax system was handed entirely over to the Royal Service for complete centralised organisation. The sudden rush of reforms led directly to the rise of plutocratic and capitalist thinking and despite the intent of the reforms being to help equalise people and break down social barriers they in fact created more. Alavarro III had not considered the wider implications of his reforms or how the fine details might change the results. Rather than implementing a system of tiered taxation based on income the Royal Service introduced a flat tax rate across the board; the Guilds continued to hold a great deal of capital and were simply able to bypass many of the restrictions on their power by creating their own investment banks and companies.

Alavarro III died in 602 ICC a widely unpopular monarch who was seen as incompetent and indecisive despite his success in rebuilding the Cartulian economy and treasury.

Late Despotismo Period (644 ICC - 810 ICC)

The Late Depotismo Period is largely defined as the transitional period between the conclusion of the High Despotismo Period and the modern day. The central feature of the Late Despotismo Period is the growth of free enterprise and capitalist economics, replacing the older caste systems and breaking down the barriers between the more traditional societal classes. The Late Despotismo Period ended in 810 ICC following the codification in that year of radical reforms to how taxation and law worked. The end of the Late Despotismo Period brought about a de facto end to the absolute power of the monarch with the introduction of the Comisión de Comercio (lit.: Commission For Trade) and the Comisión de Ingresos y Aduanas (lit.: Commission for Revenues and Customs) to manage the passage of laws and regulations relating to the economy.

Modern Era (811 ICC - Present)

The Modern Era began in 811 ICC at the turn of the year following the establishment of the dos comisiones, during the reign of Rocinante II, which marked the beginning of a series of significant constitutional reforms which have defined Rocinante II's reign and the period thus far as a whole.

Geography

Politics

Military

The armed forces of Cartulia and officially know as Las Fuerzas Armadas (lit.: The Armed Forces) or LFA for short, this includes the Marinos Real, Marina Real, and Artilleria Real. LFA is organised and managed by the Servicio Real's Oficina de Guerra which is headed by the Secretaria de Estado de Guerra (lit.: Secretary of State for War), also known as the Duqua-General, currently Andreas Gomez d'Zarajoz. The Duqua-General is appointed by the head of the Royal Service on the advice of the Comité Militar which consists of the most senior retired military officers as selected by the reigning monarch. The ceremonial commander-in-chief of LFA is the reigning Déspota, Rocinante II, however functionally the most senior military officer is the Capitán General, Juana Josephina d'Ladron. All members of LFA swear personal allegiance to the Crown.

Recruitment & Training

LFA does not recruit volunteers, rather each year it outlines its manpower needs in a formal document which is sent to the Royal Service for approval. Once approved this document is used to set a quota for recruits for each Thurhata to meet. As part of their annual taxes and tithes to the Crown each Thurhata is required to send a number of physically and mentally healthy children aged six to the capital as outlined in the LFA document; form this point onward these children are recruits of LFA. In this way LFA is as much a caste as it is an organisation, however unlike other examples of a caste systems membership is not determined by birth, and it is managed by a bureaucracy.

Upon being tithed into LFA new recruits will begin their training and education, which though rigorous, is far from inhumane for children of their age. The goal of this education and training is to build up their physical and mental faculties while at the same time instilling a careful balance of discipline, loyalty, and initiative. Throughout the first ten years of their training recruits are constantly tested, allowing them to be sorted into more specific training programs based upon their particular skills and abilities; this process is not universally successful and those individuals who prove ill-suited for any specific role or training available will receive training to be a Soldado de Marina Soldado Regular or Soldado Arquero. At the age of sixteen all recruits are sorted for the final time and enter basic military training; for the bulk of recruits this means training to be a Soldado, the general term for an infantry soldier, however for those who excelled in specific areas and met the criteria for other training a wider variety of training courses become available.

Trainee Soldados remain recruits in training for a further four years, but may be deployed onto the battlefield as needed once the first year of training is complete. Trainees in more specialised roles may undergo training for a longer period.

Marinos Real

The Marinos Real, or Royal Marines, are the core land based troops of Cartulia. Due to Cartulia's nature as a trading and maritime nation however, all ground troops are specifically trained to operate and fight on board a ship and on land. The Marinos Real take all the Soldados Regular and Soldados Arquero recruits, as well as other specialised recruits. The majority of the Marinos Real forces are infantry, with the largest single type of soldier being the Soldados Regular. The backbone of the Marinos Real however are the Infanteria de Asta, Infanteria de Espada, and Infanteria de Ballesta which are formed into Tercios. These infantry formations are supported by a limited force of cavalry and mounted infantry. All members of the Marinos Real are issued the same matching uniform, a dark blue doublet, with plain brown calico trews, black leather knee boots and gloves; additionally each carries with them a standard soldiers field kit containing rations, water carriers, tools, cleaning materials, and other basics. When at sea, or during high summer it is traditional for soldiers to wear dark blue jerkin over a plain white shirt.

Soldados

Soldados are by far the largest general unit type in LFA. They are also the lowest esteemed and ranking of Cartulia's soldiery. Consisting of those individuals who lacked the aptitude or skill for more advanced or specialised training, the Soldados will make up the bulk of any fighting force and will be expected to be the first to engage the enemy. Less well armed and armoured than the Infanteria, the Soldados are nevertheless well trained and constantly drilled to instil discipline and as such tend to have greater morale than other similarly equipped soldiers. However Soldados are ultimately viewed as expendable, and lack the manoeuvrability of better trained troops, they can best be described as aggressively average.

Soldados Regular are the regular foot infantry placed at the front of the army. Equipped with a plata and gladius as their primary weapon, each carries three pila as well. Soldados Regular are trained to fight in close formation and maintain discipline at all times; much of their battlefield strategy revolves around the formation of a shield wall and the use of their pila. Their other equipment aside Soldados Regular wear a bronze breastplate over gambeson and a morion. The Soldados Regular gained their name, which literally means regular soldiers, from the fact that formations of soldiers equipped in this fashion have been employed as the main form of infantry for Cartulia throughout it history, ever since Corto I unified the nation; the result being that other types of soldier are often compared with the Soldados Regular as a point of reference.

Soldados Arquero are foot archers employed as skirmishers intended to support formations of Soldados Regular are they advance. Equipped with a reflex bow, a escudon, and a gladius. Soldados Arquero are trained to fight in loose formations and provide constant ranged fire for the Soldados Regular; their equipment and training also enables them to fight at close quarters, though they are not dedicated melee infantry. Aside from their weapons and equipment Soldados Arquero wear a leather breastplate over gambeson, and wear a Morion. The Soldados Arquero formed the basis of Corto I's ranged infantry during the unification of Cartulia, but throughout the years have been relegated to a much lesser position with the introduction of crossbows. Dawi are not typically known for their skill at archery, and Soldados Arquero are not expected to shoot with great accuracy, just in great volume, before retreating back behind the shield line of Soldados Regular.

Infanteria

Infanteria make up the backbone of LFA. They are well trained, disciplined soldiers who have received excellent training and better equipment than the Soldados. Most Infanteria are the successful product of the LFA training and recruitment system, chosen for their aptitude from an early age, however there are some who have risen from the ranks of the Soldados through experience and skill. To be an Infanteria is to be a dependable mainstay of any Cartulian army; the Soldados may go in first, but they are always expected to fail and break, or die, it is the Infanteria who get the job done. Better equipped than lesser troops, and constantly trained and drilled in their use, as well as in the various formations and strategic manoeuvres that are expected of them, the Infanteria are in all ways superior to the Soldados.

Infanteria de Asta are pikemen and make up a third of the Infanteria Tercios formations. Equipped with a long pike they also have a machete and escudon as a back up. Infanteria de Asta are trained to fight in the core Tercio formations, maintaining cohesion and discipline at all times; they have a very specific job within the Tercio which they are trained for rigorously, however they are also well drilled and trained in what to do should circumstances on the field change, hence the machete and shield. Unlike the Soldados Regular who rely upon block formations fronted by a shield wall, Infanteria de Asta are trained to rely upon the versatility of the Tercio and unlike a Soldado unit will not break ranks and flee just because the formation has been breached. Aside from their weapons each Infanteria de Asta wears a steel cuirass with thigh guards, and a morion, as well as plated gauntlets.

Infanteria de Espada are swordsmen and make up a third of the Infanteria Tercios formations. Equipped with an espada, steel plated escudon, and javelins. Infanteria de Espada are trained to fight in the core Tercio formations, maintaining cohesion and discipline at all times. As with the Infanteria de Asta they are also trained to cope with contingencies and as used as a holding force should the pike wall be breached or the formation be broken. Infanteria de Espada have a higher proportion of soldiers who have risen from the ranks of the Soldados, due to the similarities between the Soldados Regular and the Infanteria de Espada. Aside from their weapons Infanteria de Espada wear a steel cuirass with tassets, shoulderplates, and armguards, plated gauntlets, and a morion.

Infanteria de Ballesta are crossbowmen and make up a third of the Infanteria Tercios formations. Equipped with an arbalest and a machete. Infanteria de Ballesta are trained to fight in the core Tercio formations, maintaining cohesion and discipline at all times. Infanteria de Ballesta see more discipline drill than other Infanteria in order to maintain their efficacy as a volley shot unit; they are also trained on how to respond to contingencies such as a breach on the formation and are equipped with a machete for just such a reason. Soldados seldom rise from the ranks into the Infanteria de Ballesta, the differences between the operation of a crossbow and a reflex bow are too great and the skills and experience gained by the Soldados Regular seldom make good crossbow troops. Aside from their weapons Infanteria de Ballesta wear a steel cuirass with tassets, arm guards, and a morion.

Culture

Economy

Good Produced

| Item | Item Type | Image | Examples | Details | Exported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | Mineral |

|

Refined iron ingots, tools, armour, weapons, steel |

Iron is one of the main mineral resources found in Cartulia. Mined extensively throughout the nation it forms the basis of much of the Cartulian metalworking industry, whether it is formed into steel or kept (relatively) pure for other purposes. The iron mining and working industries in Cartulia are vast and extensive with the Ironworker's Guild being one of the largest, wealthiest, and most prestigious of the nation's guilds. Iron has been extracted, refined, and worked in Cartulia since time immemorial, though in the Iblesian Dawi folklore and mythology it is seen as a fickle and unreliable metal unless tempered with another material for its softness and tendency to rust. | Yes |

| Bronze | Alloy |

|

Bronze ingots, tools, armour, weapons |

Objects made from bronze have been manufactured in Cartulia in one form or another for millennia. The earliest extant examples of bronze tools dates back at least four thousand years and the legendary Dawi hero Cartu Zothrazviraminan was said to have used a cast bronze warhammer in battle. Although the use of bronze in weapons and armour has largely given way to the use of iron and later steel the manufacture of bronze and bronzeware remains a strong part of the nation's industry with domestic products, tools, decorative items, and jewellery rendered in the material remaining popular. The Menta Real even issues a bronze coin. | Yes |

| Steel | Alloy |

|

Steel ingots, tools, armour, weapons | The development of steel from iron took root in Cartulia fair back in the nation's history and its properties made it highly sought after and much preferred to iron or bronze. Experimentation with the production of steel in terms of the properties, quality, and quantity that could be manufactured became a matter of great interest and Cartulian steelsmiths rapidly developed their own favoured techniques. Modern Cartulia produces two principle kinds of steel in sizeable quantities; Alcázarra and Cartulian steel, both of which are exported as ingots or actual materials. | Yes |

| Copper | Mineral |

|

Copper ingots, refined copper currency, tools, armour, weapons, jewellery, domestic goods, bronze | Cartulian Copper is mainly used in the production of Bronze, however there is a chartered guild known as the Guild of Copper and Redsmiths, which focuses solely upon the refining and use of pure copper. While copper weapons and armour are still manufactured these are usually ornamental pieces, or made by specific request rather than in bulk; generally Cartulian copperware takes the form of cooking pots and utensils with little to none being exported abroad. The lowest denomination of the Cartulian currency, the Faisa, is rendered in copper. There are two major copper mines in Cartulia. | No |

| Gold | Mineral |

|

Gold ingots, refined gold currency, jewellery, bullion, alloys | Gold is one of the most valued metals to the Dawi of Cartulia. Its most common use is in the creation of currency and bullion, with ten silver Talents being worth on gold Baza. The Royal Mint in Castillo Alcázarra is renowned for the quality and reliability of the coins it produces and the goldsmiths and coinstrikers who work for the mint are held to extremely high standards to ensure that the currency and bullion they produce are of the highest standards of purity. Besides its use as currency the trade in gold ornaments and jewellery is a popular one; gold is used as a means of showing wealth and status and so the Guilds of Goldsmiths and Jewellers earn a great deal of prestige and many wealthy patrons. There is only one active gold mine in Cartulia which is located on the island of Iblesia. | Yes |

| Silver | Mineral |

|

Silver ingots, refined silver currency, jewellery, bullion, alloys | Silver is the primary measure of an item's value in Cartulia with the nation's currency the Talent being rendered in silver. The value of everything, even more valuable materials such as gold, is given in silver and it is not uncommon for a Cartulian trader or artisan ask what a thing is worth by weight in silver. There is no guild of silversmiths, this is because the processing of raw silver into usable ingots is entrusted solely to the Royal Mint. Jewellery made using silver is still quite popular and so the Guild of Jewellers is allowed to purchase bars of refined silver for use in the production of ornaments and trinkets. The ownership of silver ore and unminted silver is tightly controlled within Cartulia. | No |

| Coal | Mineral |

|

Fuel | The rock which fuels the industrial economy of Cartulia is coal. Vast quantities of coal are needed and used on a daily basis in order to heat the forges of craftsmen across the nation; however despite the quantities extracted from the earth every day the country is incapable of producing enough coal to meet its needs and so the fuel is expensive and banned from export. Coal mining is a dangerous process and is seen by most of Cartulian society as a demeaning profession, as such the nation's coal mines are owned by the state and run using convict labour. The sentence for most crimes is a stint in the coalmines. | No |

| Wheat | Agricultural |

|

Grain, flour, bread, baked goods, alcohol | Wheat is the primary crop grown in Cartulia and is cultivated on a grand scale. Major advances in farming techniques and technologies over the last two hundred years have increased crop yields, yet with the majority of the population living and working underground there is still not enough wheat for export. Wheat forms the basis of the agrarian side of the nation's economy and food stores and stockpiles for winter and for emergencies mainly consist of wheat and wheat flour. Much of the cultivated land in Cartulia is owned by one or other of the many merchant companies, there is no guild of wheat farmers though specific trades related to wheat produce do have their own guilds. | No |

| Barley | Agricultural |

|

Grain, flour, alcohol | Barley is primarily grown for use in fermentation and distillation. Unlike the farming of grain the cultivation of barley is controlled by two guild, though somewhat indirectly, the Guild of Brewers and the Guild of Distillers. Since it is primarily seen as an ingredient and not a source of food in itself the exportation of barley and barley products is not uncommon. | Yes |

| Oats | Agricultural |

|

Grain, flour, alcohol | Oats form the basis of the working class's diet, and is a staple of the entire nation's diet. Used primarily to make porridges, stews, and oatcakes. The growing of oats is a requirement for any company that wishes to own farmland, and oats are the primary crop of subsistence farmers. No guild of oat farmers exists because the farming of oats is considered to be a subsistence right; unlike with the cultivation of wheat however most of the oats grown in Cartulia are grown on land owned directly by the Bazh and not a company. | No |

| Temperate Vegetables | Agricultural |

|

Parsnip, Carrot, Beetroot, Turnip, Onion, Leek, Rhubarb | Vegetable cultivation in Cartulia takes place both above and below ground and, unusually for agricultural producers vegetable cultivation is governed by a guild. The Guild of Gardeners and Greengrocers was chartered by royal decree in 321 ICC shortly after the abolition of serfdom as a means of ensuring the continued cultivation of vegetables and preventing vegetable prices from rising as free farmers started to grow 'easier' crops that were more profitable. The Guild of Gardeners and Greengrocers is not however allowed to sell its produce overseas. | No |

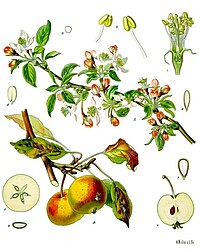

| Temperate Fruits | Agricultural |

|

Apples, Pears, Peaches, Strawberries, Raspberries, Blackberries, Sloes, Olives | The cultivation of fruit is managed by the Guild of Gardeners and Greengrocers, although certain fruits such as apples, pears, and grapes can also be cultivated by the Guilds of Cidermakers and Vintners. As with vegetable cultivation there was a concern following the abolition of serfdom that the cultivation of fruit would decline leading to rising prices of both fruit and fruit products such as cider and wine; under the Royal Charter of the Guild of Gardeners and Greengrocers however the prices stabilised over time and production improved to the point where, unlike vegetables, fruit could be exported. | Yes |

| Medicinal Herbs | Agricultural |

|

Garlic, Fennel, Nettle, Borage, Aloe, Mint, Elder, Marigold, Shea | The cultivation of medicinal herbs is managed by the Guilds of Herbalists and Apothecaries, though forage laws allow subsistence farmers and hunters to collect wild herbs. Extensive work and cultivation over centuries have enabled the Guild of Herbalists to grow large quantities of herbs for medicinal purposes, and they have even succeeded in vastly increasing the number of harvestable shea and acacia trees in the nation. The majority of the medicinal herbs and goods that are exported are prepared by the Guild of Apothecaries. | Yes |

| Medicinal Alchemy | Crafted |

|

Tonics, Tinctures, Salves, Poultices, Potions, Ungents | Medicinal Alchemy is a major business in Cartulia; under the reforms of Rocinante I in the 3rd century ICC the Royal Society for Alchemical Research and the Royal Academy of Alchemy were both established providing alchemists with government funding and a formal system of education. The Society and Academy predate the creation of the guild system, and are considered to be prestigious institutions. The products of medicinal alchemy are widely exported. | Yes |

| Medicinal Apothecaric Goods | Crafted |

|

Tonics, Tinctures, Salves, Poultices, Ungents | The products of apothecaries are treated differently to medicinal alchemy. Where medicinal alchemy involves the arcane and in some cases magical knowledge Medicinal Apothecaric Goods are produced along more scientific lines and lack the involvement of magic or ritual. | Yes |

| Research Books | Intellectual |

|

Medicinal, Herbal, Metallurgical | The various Royal Societies and Academies promote the publishing of various academic texts, many of which are exported, as a means of drawing in extra income for their members and graduates. Cartulia specialises in the fields of medicinal alchemy, herbalism, and metallurgy. | Yes |

| Whale Products | Aquaculture |

|

Bone, fat, oil, ambergris, meat | Whaling is a significant industry in Cartulia. Whales provide meat for food, blubber and fat for various uses including heating and light, bone for crafting items, ambergris for alchemical use, and hides which are used as a building material and fabric substitute. Every part of a whale is used with nothing going to waste; developments in technology are increasing the demand for whale oil and fat for the provision of heat and light, and tools and weapons made from whale bone are lightweight and resistant to corrosion while at sea. Even as an ornamental medium whale bone is prized, used for statuary, scrimshaw, and in jewellery, clothing, and accessories. Ambergris meanwhile is used in alchemy, medicine, and perfumery. | Yes |

Goods Imported

| Item | Item Type | Image | Examples | Details | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timber | Natural | File:Freshlycutlogs.JPG | Oak, Pine, Rowan, Ebony | As a maritime nation with large and well developed shipyards Cartulia uses a great deal of timber in shipbuilding. Cities and homes are largely made from stone, but the military and merchant companies alike rely on timber, and thus a great deal must be imported from overseas. While the growth and cultivation of rowan, shea, and acacia are widespread these woods are not best suited for shipbuilding and with only limited woodlands to take advantage of, Cartulia alone cannot produce sufficient timber. The balance must also be made between charcoal manufactures and the use of timber for construction. | Ras Vertaz |

| Copper Ore | Mineral |

|

Only ores, refinery takes place in Cartulia. | Although Cartulia produces a great deal of copper ore to begin with the amount of bronze being produced, and the appetite for raw materials, mean that more is always needed. | |

| Tin | Mineral |

|

Refined ingots and ores. | Cartulia only has minimal tin deposits and the demand for bronze goods outstrips the possibilities given the domestic tin supply therefore it is necessary to import quantities of tin, both ore and refined, for bronze production. | |

| Textiles | Crafted |

|

Wool, silk, cotton | ||

| Gems | Mineral |

|

Uncut gems | ||

| Silver | Mineral |

|

Silver ingots, silver ore | ||

| Coal | Mineral |

|

Fuel | ||

| Wine | Produce |

|

Red, White, whatever | ||

| Whale Products | Aquaculture |

|

Bone, fat, oil, ambergris, meat |