The Libertines: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

... | ... | ||

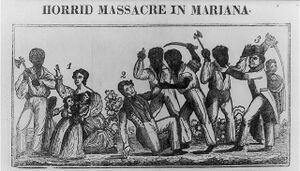

[[File:Horrid Massacres in Mariana.jpg|right|300px|An Augustan woodcutting dating from the Libertine Revolution depicting the "horrid massacres" of the plantation owners and their families.]] | [[File:Horrid Massacres in Mariana.jpg|thumb|right|300px|An Augustan woodcutting dating from the Libertine Revolution depicting the "horrid massacres" of the plantation owners and their families.]] | ||

The two states following the Augustan withdrawal were far from the safe havens they were proclaimed to be. Several key problems presented themselves. In many cities, the news of independence was met with rioting and racial violence. Plantation owners and their families were harassed, attacked, and ultimately driven out of the country to Augusta or overseas to Albion. Some, rather than leave, fled to isolated areas to become guerrillas, awaiting a hypothetical Augustan reconquest that would restore their position. White citizens who were sympathetic to the slavers were also driven out at gunpoint. This resistance was soon dealt with by the Libertine militias, as well as Arcadian soldiers themselves, who worked to guarantee the violence did not spread to working class white citizens. Some of these white citizens became active members of the new order, recognising that independence would lead to increased social and economic mobility for them as well. White Arcadian abolitionists, such as Hanson Lewis, also settled in the newly liberated republics. Despite the security afforded by the number of Arcadian troops in the most urbanised areas of Liberty and Freedland, there was still a large power vacuum in most of the countryside. These rural areas, suffering a power vacuum, became self-managed by former slaves, who set up their own communities and townships. Others became the domain of militia leaders who found their power unchecked, some becoming defacto warlords in their own right. Some of these warlords, including [[Captain Harry Coffee]], [[Quamana Sam]], and Cyrus Clay himself, were able to negotiate with the newly established governments and became politicians and figures of authority in the new governments. Others, such as the infamous bandit [[Black Jack Cuddjoe]], had to be hunted down and eliminated. | The two states following the Augustan withdrawal were far from the safe havens they were proclaimed to be. Several key problems presented themselves. In many cities, the news of independence was met with rioting and racial violence. Plantation owners and their families were harassed, attacked, and ultimately driven out of the country to Augusta or overseas to Albion. Some, rather than leave, fled to isolated areas to become guerrillas, awaiting a hypothetical Augustan reconquest that would restore their position. White citizens who were sympathetic to the slavers were also driven out at gunpoint. This resistance was soon dealt with by the Libertine militias, as well as Arcadian soldiers themselves, who worked to guarantee the violence did not spread to working class white citizens. Some of these white citizens became active members of the new order, recognising that independence would lead to increased social and economic mobility for them as well. White Arcadian abolitionists, such as Hanson Lewis, also settled in the newly liberated republics. Despite the security afforded by the number of Arcadian troops in the most urbanised areas of Liberty and Freedland, there was still a large power vacuum in most of the countryside. These rural areas, suffering a power vacuum, became self-managed by former slaves, who set up their own communities and townships. Others became the domain of militia leaders who found their power unchecked, some becoming defacto warlords in their own right. Some of these warlords, including [[Captain Harry Coffee]], [[Quamana Sam]], and Cyrus Clay himself, were able to negotiate with the newly established governments and became politicians and figures of authority in the new governments. Others, such as the infamous bandit [[Black Jack Cuddjoe]], had to be hunted down and eliminated. | ||

Revision as of 14:56, 12 September 2022

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

The Free Republic of the Libertines | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

Motto: "Unity, Freedom, Equality" | |

Anthem: "The Song of the Libertine" | |

| Map of the Libertines Map of the Libertines | |

| Capital | Freeport |

| Recognised national languages | Albian |

| Recognised regional languages | Marianan Creole, Geesee |

| Demonym(s) | Libertine |

| Government | Semi-Presidential Republic |

• President | Michelangelo Masters |

• Prime Minister | Toni Cain |

| Legislature | Libertine Congress |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Establishment | |

• Erisian Colonisation | 1540s |

• Vailleux Colonisation of Mariana | 1609 |

• Alban Colonisation | 1765 |

• Libertine Revolution | 1830 |

• Establishment of the Free Republic of the Libertines | 1844 |

• Establishment of the National State of the Libertines | 1935 |

• Restoration of the Free Republic of the Libertines | 1939 |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 30,000,000 |

• 2017 census | 27,812,520 |

| Currency | Libertine Dollar (LD) |

| Date format | mm ˘ dd ˘ yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Internet TLD | .lib |

The Libertines, also known as the Free Republic of the Libertines, is a country located in eastern Arcadia. Divided into five states, the Libertines is approximately ... square kilometres in size, and is comprised of around 30,000,000 Libertine citizens. The Libertines is bordered by Hochland to the southeast, the Fraternal States of Augusta to the south, and the Federal Union of Arcadia to the west and northwest. The capital of the Libertines is Freeport.

The Libertines were originally inhabited before Erisian colonisation by indigenous Arcadians such as Sugeree, Croatoan, Chalakee, Yuchi, and Chowanoke peoples. Erisians first arrived in the area in the 1540s, and had begun to create several small settlements and trading posts. By the late 1600s Vailleux had taken control of the region, forming it into the colony of Mariana, named after the Vailleux Queen Maria d'Arba. It was in the first years of the 18th century that the first Maurians would arrive as slaves, and over the next century they would comprise a majority of the population. After the Nine Years War, the region came under Alban domination in 1765, taking control of the formerly Vailleux settlements, and dividing the region into two separate colonies, Mariana and Pleasantia.

In the midst of the Arcadian War of 1829 between Arcadia and Alba, a slave by the name of Cyrus Clay sparked a revolt in Mariana in 1830, beginning the Libertine Revolution. Clay's forces allied with Arcadian soldiers who were in the process of invading the region, offering aid in exchange for the training of Clay's men to act as a more organised force. The success of these forces at the end of the War of 1829 in 1833 saw the territories of Mariana and Pleasantia given to the survivors of Clay's Revolt, which were renamed to Liberty and Freedland and proclaimed as independent republics. The next year, in 1834, the two republics merged into the Provisional Republic of the Libertines as a response to the withdrawal of Arcadian troops from the region, officially ending the Libertine Revolution. The provisional Freedmen's Council, a directorate made of several representatives, governed the Libertines until the establishment of the Free Republic of the Libertines in its first election in 1840.

Close relations with Arcadia allowed the Libertine economy to gain a head start, and philanthropists from across the Western world invested money in educational programmes and Libertine institutions. Efforts to industrialise the country throughout the 1860s and 1870s, especially the creation of a nationalised rail network along with a boom in the textile industry, ensured that the Libertines would not be reliant on an agrarian economy. Relations with the newly independent Federated States of Augusta to the south however, remained near-hostile, especially as Augusta continued to practise the enslavement of Maurian-Arcadians on plantations. Tensions between the Libertines and Augusta such as the Jones Affair in 1860 would continue over the rest of the 19th century, ultimately leading to the War of 1899. The War, costly to both Augusta and the Libertines, ended in an Arcadian-mandated ceasefire and peace treaty in 1902, which led to deep dissatisfaction in both Augusta and the Libertines. In 1932 a Libertine ultranationalist by the name of Noah Stonewall was elected president, and in 1935 Stonewall disbanded the government with the help of his loyalist paramilitary forces and announced the creation of the National State of the Libertines, in which he would serve as dictator. Stonewall's government was deposed in 1939 and democracy was restored. Relations with Augusta would improve, especially after the ... Accords of 1979.

The Libertines today are a semi-presidential republic, and is described as a liberal democracy, ranking highly in areas of quality of life, of education, and of economic freedom. However, the Libertines also retains capital punishment, has fairly high rates of incarceration, and corruption, while below the world average, is not insignificant. The Libertines possess a rich cultural heritage, in particular that of Mauro-Arcadian culture, and is a major tourist destination in Arcadia. Libertine music, has become popular worldwide since the 1950s, has had a significant impact on popular music. This is especially true for the genres of jazz, rhythm, blues, rock, Catflap, snap, and hip-hop, which all have their origins at least partially or entirely from the Libertines.

Etymology

History

Pre-Colonial History

Erisian Colonisation

The Libertine Revolution

As Arcadian troops and Libertine militias took more land from Albionian-Augustan troops, a proclamation was sent out by Arcadian President James McClintock, stating that the territories of Mariana and Pleasantia would be liberated and given to the survivors of Cyrus Clay's rising as independent nations. Shortly after this proclamation, hundreds of educated Mauro-Arcadian lawyers, merchants, and politicians flooded into these newly liberated territories, setting up political organisations and aiding in rebuilding efforts in anticipation of the area's independence. Many were encouraged by the Arcadian government, who had seen in the independence of these territories a solution to the problem of educated Mauro-Arcadians who had been advocating for political and social change.

...

The two states following the Augustan withdrawal were far from the safe havens they were proclaimed to be. Several key problems presented themselves. In many cities, the news of independence was met with rioting and racial violence. Plantation owners and their families were harassed, attacked, and ultimately driven out of the country to Augusta or overseas to Albion. Some, rather than leave, fled to isolated areas to become guerrillas, awaiting a hypothetical Augustan reconquest that would restore their position. White citizens who were sympathetic to the slavers were also driven out at gunpoint. This resistance was soon dealt with by the Libertine militias, as well as Arcadian soldiers themselves, who worked to guarantee the violence did not spread to working class white citizens. Some of these white citizens became active members of the new order, recognising that independence would lead to increased social and economic mobility for them as well. White Arcadian abolitionists, such as Hanson Lewis, also settled in the newly liberated republics. Despite the security afforded by the number of Arcadian troops in the most urbanised areas of Liberty and Freedland, there was still a large power vacuum in most of the countryside. These rural areas, suffering a power vacuum, became self-managed by former slaves, who set up their own communities and townships. Others became the domain of militia leaders who found their power unchecked, some becoming defacto warlords in their own right. Some of these warlords, including Captain Harry Coffee, Quamana Sam, and Cyrus Clay himself, were able to negotiate with the newly established governments and became politicians and figures of authority in the new governments. Others, such as the infamous bandit Black Jack Cuddjoe, had to be hunted down and eliminated.

Additionally, the problems of refugees and ongoing hunger had to be dealt with. By the terms of the peace deal, all slaves above the ... parallel were to be freed, transferred to Arcadian authorities and then transported to the newly established republics of Liberty and Freedland. Even though many Augustan plantation owners above the ... parallel refused to give away their slaves, or cheated the system by assigning them to plantations further south, many newly freed and escaped slaves had found themselves in Libertine territory with no homes and few belongings. Because farms were left unplanted from the turmoil, and with no guarantee of a reliable food supply, many of these refugees along with regular citizens, starved. During the winter of 1833-1834 thousands died of hunger or exposure.

Along with all this, there still was the threat of Augustan troops invading once Arcadian troops had withdrawn from Liberty and Freedland. The timing was difficult; information delivered to the governments of both Liberty and Freedland by Arcadian General Horatio Lee Oliver stated Arcadia's intent to withdraw from the republics within two years, amid domestic demands to demobilise. Both President-Executive William Brownstone of Liberty and President-Executive Benjamin Priest of Freedland soon recognised that to survive, both republics had to unite into a single nation. After months of negotiation, the Republic of Freedland and the Republic of Liberty officially merged to become the Provisional Republic of the Libertines on the 2 January 1834, ending the Libertine Revolution.

19th Century

Three Weeks' War

Fears of Augustan invasion would be proven correct. Six months after the Arcadian withdrawal, on the 7th of September 1836, soldiers of the Fraternal States of Augusta streamed across the border, seizing border outposts and fortifying positions, where they met heavy resistance from Libertine soldiers. The Augustan justification of the war, stated by President ..., was to "restore order to the provinces of Mariana and Pleasantia, illegally severed from Augusta; which have succumbed into a state of black anarchy that risks spreading banditry and insurrection." There was a clear emphasis to destroy the newly formed nation, as the Libertines were seen as a threat to the institution of slavery within Augusta itself. Though the Libertines had expected that Augusta would attack and seek to destroy the nascent republic as soon as Arcadia withdrew their forces, the speed of the Augustan attack took the Libertine government by surprise. By the 10th of September, the towns of Harpersboro and Liberty Hill had been captured and were subject to looting, and Libertine forces were forced to withdraw from much of Chalakee.

However, the Augustan advance, led by the Army of Midland under the command General Sidney Wells, faced several immediate problems that ground their advance to a halt by the 12th. The first problem was that Augustan troops were fundamentally undersupplied and underequipped. There was a strong hope that the Augustan army would be able to scavenge supplies along the way, especially as it was believed that Libertine troops would retreat and leave behind stockpiles of ammunition and weapons. The already poor situation of Augustan supplies were made worse by Libertine militias which had quickly been raised and then engaged in guerrilla fighting. These militias, which had experience in fighting in the Chalakee Mountains during the Revolution only several years ago, were able to effectively harass and disrupt the Augustan supply line. Additionally, heavy rain and floods between the 10th and 12th swept away many of the mountain trails through the Chalakee Mountains, worsening the situation. At the Battle of Bluefield on the 16th, the Augustans were dealt their first major defeat by Libertine troops under the command of Baptiste Andry. This was followed by the Battle of Mt Pound on the 19th and the Battle of Fruit Hill on the 20th, which forced Augustan soldiers back to the gains made on the first few days. Several days later, this was followed by the Battle of Harpersboro on the 23rd, where brutal hand to hand fighting for the town forced Augustan troops to flee further towards the border. In the aftermath of Harpersboro, Libertine militias were able to pick off and capture hundreds of retreating Augustans with great effectiveness, and General Sidney Wells was fatally shot by a Libertine sniper on the morning of the 24th. Augustan forces had retreated back to the border by the 25th.

While Libertine citizens were jubilant at these victories, feeling secure in the Libertines' future, Augustan politicians were outraged. Rumours of torture and mutilation by Libertine troops, and the fact that hundreds of soldiers had been captured sparked resentment to the campaign. Among many others, the lead opponent to the war was Senator Joseph Cannady of New Ostend. In a speech on the 23rd of September, Senator Cannady decried the inability of the government to "protect their soldiers from the cruel tortures of the blacks", and spoke publicly on ending the war, stating that "I'd rather our boys protect our institutions here than be scalped on some cursed mountain." On the 31st of September 1836, 24 days after the campaign had begun, a ceasefire was signed, officially ending conflict; there would continue to be sporadic but low level border conflicts for the next decade afterwards until the Augustan government recognised the independence of the Libertines in 1850.