Anachak Kang: Difference between revisions

m (→Ancient Kra) |

No edit summary |

||

| (31 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Nev's Article]] | [[Category:Nev's Article]] | ||

{{WIP}} | {{WIP}} | ||

{{Infobox country | {{Infobox country | ||

| Line 24: | Line 15: | ||

|symbol_type = Emblem | |symbol_type = Emblem | ||

|national_motto = ສະບາສະມາ ສັງຂາບພຸດໂທ ສັງຂານສະມະກິ ວຸທິສາທິກາ<br>{{small|"For the harmory of all the people, to prosper and to succeed"}} | |national_motto = ສະບາສະມາ ສັງຂາບພຸດໂທ ສັງຂານສະມະກິ ວຸທິສາທິກາ<br>{{small|"For the harmory of all the people, to prosper and to succeed"}} | ||

|national_anthem = Pheng Xat Kra<br>"Hymn of the Kra"<br>[[File:MediaPlayer.png|link=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= | |national_anthem = Pheng Xat Kra<br>"Hymn of the Kra"<br>[[File:MediaPlayer.png|link=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ekmecUtAu3Q|210px]] | ||

|image_map = Location of Anachak Kang map.png | |image_map = Location of Anachak Kang map.png | ||

|map_width = 275px | |map_width = 275px | ||

| Line 51: | Line 42: | ||

|government_type = {{wp|Unitary State|Unitary}} {{wp|Parliamentary system|parlimentary}} {{wp|Anocracy|anocratic}} {{wp|Semi-constitutional monarchy|semi-consitutional monarchy}} | |government_type = {{wp|Unitary State|Unitary}} {{wp|Parliamentary system|parlimentary}} {{wp|Anocracy|anocratic}} {{wp|Semi-constitutional monarchy|semi-consitutional monarchy}} | ||

|leader_title1 = Monarch | |leader_title1 = Monarch | ||

|leader_name1 = [[ | |leader_name1 = [[Chao Souk]] | ||

|leader_title2 = Prince Regent | |leader_title2 = Prince Regent | ||

|leader_name2 = [[ | |leader_name2 = [[Khun Khanthavong]] | ||

|leader_title3 = Prime Minister | |leader_title3 = Prime Minister | ||

|leader_name3 = [[Koa Cheruene]] | |leader_name3 = [[Koa Cheruene]] | ||

| Line 109: | Line 100: | ||

Modern Kra traces its origins to a cradle of civilisation in the fertile Maena river basin in the Central Kra Plain. Their long occupation, initially in varying forms of hunter-gatherers, emerged into settled life 7,000 years ago, gradually evolving into the Maena Basin Civilisation of the third millennium BCE. By 1400 BCE, an archaic form of {{wp|Sanskrit|Sombhang}}, an Ochran-Malaio language, had diffused into the Kra peninsula from the southwest. Its evidence today is found in the hymns of the ''{{wp|Rigveda|Samaphidthanya}}''. Preserved by a resolutely vigilant oral tradition, the Samaphidthanya records the dawning of {{wp|Hinduism|Sadthaism}} in Anachak Kang. | Modern Kra traces its origins to a cradle of civilisation in the fertile Maena river basin in the Central Kra Plain. Their long occupation, initially in varying forms of hunter-gatherers, emerged into settled life 7,000 years ago, gradually evolving into the Maena Basin Civilisation of the third millennium BCE. By 1400 BCE, an archaic form of {{wp|Sanskrit|Sombhang}}, an Ochran-Malaio language, had diffused into the Kra peninsula from the southwest. Its evidence today is found in the hymns of the ''{{wp|Rigveda|Samaphidthanya}}''. Preserved by a resolutely vigilant oral tradition, the Samaphidthanya records the dawning of {{wp|Hinduism|Sadthaism}} in Anachak Kang. | ||

The | The Maena Basin Civilisation would help set the foundation of several regional cities that would turn into city-states and petty kingdoms. The semi-legendary kingdom of Muang Sua in the 21st century BC, the subsequent well-attested Kingdom of Lan Na and Chiang Mai, and the Kingdom of Lan Xang would help develop a unique regional political system known as the ''{{wp|Mandala (political model)|Aeuad}}''. Kra writing, Kra classic literature and the Hundred Schools of Thought emerged during this period and influenced the inhabitants of the Kra peninsula for centuries to come. These Kra petty kingdoms would remain disunited until the third century BCE when Prince Fa Ngum of Viangchan's war of unification created the first Kra empire, the short-lived Fa dynasty. The more stable Baasac dynasty (206 BCE – 220CE) followed the collapse of the Fa, which established a model for nearly two millennia in which the Kra empire was one of the world's foremost economic powers. The empire expanded, fractured and reunified, was conquered and reestablished, absorbed foreign religions and ideas, and made world-leading scientific advances, such as the Five Great Inventions: mathematics, astronomy, the compass, paper, and printing. After centuries of disunion following the fall of the Baasac, the Ngoenyang (581 – 618) and Nanthavong (618 – 907) reunified the empire. During the time of the 3rd emperor of the Nanthavong dynasty, Nanthavong Khampong united the entirety of the Kra peninsula for the first time and introduced the first imperial examination system, creating a new civilian scholar-officials or literati class to replace the aristocratic military class of earlier dynasties. He also reintroduces old philosophical schools of thought such as Legalism* and Neo-Confucianism* to centralise power onto the monarch. However, his reforms would eventually become undone after a series of weak successive monarchs, allowing the Bayarid Empire to invade and occupy the nation successfully in 932. The Bayarid invasion established Anachak Kang as a semi-autonomous vassal state and compulsory ally of the Bayarids and its successor, the Great Khan's Court-in-Taizhou*. Anachak Kang would remain under the control of the Khan's Court until the Na dynasty (1358–1674) reestablished ethnic Kra control. | ||

The Na dynasty peaked in the 17th century, until its destruction in the XXX–Kra War. Khampheng Kamchanh quickly reunified the fragmented territories and established the short-lived Khampheng dynasty (1678–1707). She was succeeded in 1707 by Kham Paxathipatai Siharath, the first monarch of the current Kham dynasty. Throughout the era of foreign imperialism in Ochran-Malaio, Anachak Kang was relatively untouched. However, the dynasty faced drastic changes in the world system; foreign intrusion, internal revolts, population growth, economic disruption, official corruption, and the reluctance of the scholar-official elites to change their traditionalist ways and mindset. With peace and prosperity, the population rose to some 90 million, but taxes and government revenues were fixed at a low rate, soon leading to the 1861 Fiscal Crisis. The Xiengthong Rebellion (1861-1875) and the Tha Khek Revolt (1875-1881) in Northern Anachak Kang led to the deaths of over 1 million people from famine, disease, and war. The Xriya Restoration in the 1890s brought vigorous reforms and the introduction of foreign military technology in the Self-Strengthening Movement. However, defeat in the | The Na dynasty peaked in the 17th century, until its destruction in the XXX–Kra War. Khampheng Kamchanh quickly reunified the fragmented territories and established the short-lived Khampheng dynasty (1678–1707). She was succeeded in 1707 by Kham Paxathipatai Siharath, the first monarch of the current Kham dynasty. Throughout the era of foreign imperialism in Ochran-Malaio, Anachak Kang was relatively untouched. However, the dynasty faced drastic changes in the world system; foreign intrusion, internal revolts, population growth, economic disruption, official corruption, and the reluctance of the scholar-official elites to change their traditionalist ways and mindset. With peace and prosperity, the population rose to some 90 million, but taxes and government revenues were fixed at a low rate, soon leading to the 1861 Fiscal Crisis. The Xiengthong Rebellion (1861-1875) and the Tha Khek Revolt (1875-1881) in Northern Anachak Kang led to the deaths of over 1 million people from famine, disease, and war. The Xriya Restoration in the 1890s brought vigorous reforms and the introduction of foreign military technology in the Self-Strengthening Movement. However, defeat in the [[Cross-Strait War]] in 1898 led to ratifying the Treaty of Hoabinh, which saw Anachak Kang further weakened at the turn of the century. The nation was able to reverse its decline with foreign aid, most notably from the [[Latin Empire]]. It participated in the [[Hanaki War]] (1927-1929*), allying with [[Pulau Keramat]] and [[Zanzali]] against the [[Hanaki War|allies*]]. | ||

Apart from a brief period of republicanism in the | Apart from a brief period of republicanism in the 1930s, Anachak Kang periodically alternated between democratic, monarchic and military rule. Since the 2000s, the country has been caught in the continual bitter political conflict between supporters and opponents of the royalist, the democratically elected government and the military elite, stemming from a failed coup attempt in 2003. The establishment of Anachak Kang's current constitution came from a compromise between the royalist and the nominally democratic government after the 2019 Kra general election, led by Prince Regent Kham Khanthavong and the moderate Prime Minister Koa Cheruene. Since 2019, Anachak Kang has been nominally a parliamentary constitutional monarchy; in practice, however, structural advantages in the constitution due to the compromise have resulted in a complex parliamentary anocratic semi-constitutional monarchy system balanced between the military, the democrats, and the monarchist. | ||

Anachak Kang is a {{wp|Middle power|middle power}}* in global affairs and ranks relatively high on the {{wp|Human Development Index}}. It is also classified as a {{wp|newly industrialised country|newly industrialised economy}}, with manufacturing, agriculture, and {{wp|Tourism in Thailand|tourism}} as leading sectors. | Anachak Kang is a {{wp|Middle power|middle power}}* in global affairs and ranks relatively high on the {{wp|Human Development Index}}. It is also classified as a {{wp|newly industrialised country|newly industrialised economy}}, with manufacturing, agriculture, and {{wp|Tourism in Thailand|tourism}} as leading sectors. | ||

| Line 132: | Line 123: | ||

=== Ancient Kra === | === Ancient Kra === | ||

By 6500 BCE, evidence for the domestication of foods, crops and animals, construction of permanent structures and storage of agricultural surplus appeared in Bokèo and other sites in what is now Luang Namtha province. These gradually developed into the Maena Basin Civilisation, the first urban culture in Southeast Ochran, which flourished from 2500 to 1900 BCE. The Maena Basic Civilisation centred around cities such as Luang Namtha (Old City), Luang Prabang, | By 6500 BCE, evidence for the domestication of foods, crops and animals, construction of permanent structures and storage of agricultural surplus appeared in Bokèo and other sites in what is now Luang Namtha province. These gradually developed into the Maena Basin Civilisation, the first urban culture in Southeast Ochran, which flourished from 2500 to 1900 BCE. The Maena Basic Civilisation centred around cities such as Luang Namtha (Old City), Luang Prabang, Muang Na, and Chiang Mai, relying on varied forms of subsistence and engaging in crafts production and regional trade. Burial jars and other kinds of sepulchres suggest a complex society in which bronze objects appeared around the time. | ||

During the 2000–500 BCE, many cities of the Maena Basin Civilisation transitioned from the Chalcolithic culture to the Iron Age. The ''Phidthanya'', the oldest scriptures associated with Sadthaism, were composed during this period. Historians have analysed these to posit a ''Phidthanyakra'' culture in the Central Kra Plain. Most historians also considered this period to have encompassed several waves of human migration into the peninsula from the north and south across the seas. A caste system, which created a hierarchy of priests, warriors, and free peasants, emerged during this period, dividing the Kra society into the traditional lineage roles that can still be seen today. The exclusion of the migrating "Outer Kra" became prominent during this period and labelled the migrators into the Central Kra Plain as impure and untouchable. On the outer fringe of the Central Kra Plain, archaeological evidence from this period suggests the evidence of a chiefdom stage of political organisation. Influenced by the civilisation of the Central Kra Plain, they are marked with a progression to sedentary life, as indicated by the large number of megalithic monuments dating from this period, as well as by nearby traces of agriculture, irrigation tanks, and craft traditions. | |||

====Early states and the Kingdom of Muang Sua==== | |||

Oral traditions also preserved the cultural memory of the early Kra in the origin myths and practices of the Kra people. The cultural, linguistic, and political roots which highlight the commonality of these oral traditions can be traced to the ''Nithan Khun Borum'' (Kra: ນິທານຂຸນບູລົມ, lit. 'The Legend of Khun Borum'). The legend is central to these origin stories and forms the introduction to the ''Phongsavadan'' (Kra: ພົງສະຫວັນ, lit 'Court Chronicles'), which are read aloud during auspicious occasions and festivals. Throughout the history of Anachak Kang, the legitimacy of the various dynasties was tied to their relation to the historical dynasty of Khun Lo, the legendary King of Lan Na and the son of Khun Borum. | |||

According to the Nithan Khun Borum, the Kingdom of Muang Sua emerged around 2100 BCE. The kingdom marked the beginning of Anachak Kang's political system based on the hereditary leadership of a ''muang'' and the vassalised polities under it as a centre of domination. Historians describe this unique political concept as the ''Aeuad'', where the central state distributed political power amongst their vassals, and local authorities were more important than the central leadership. | |||

Historians considered Muang Sua mythical until modern scientific excavations found early Bronze Age sites at present-day Muang Sua in 1959, giving the region its namesake. It remains unclear whether these sites are the remains of the Muang Sua or another culture from the same period. The succeeding Kingdom of Lan Na and the Kingdom of Chiang Mai is the earliest confirmed by contemporary records. Lan Na and Chiang Mai ruled much of the plains surrounding the Maena River from the 17th to the 11th century BCE. Their oracle bone script (from c. 1500 BCE) represents the oldest form of Kra writing yet found and is a direct ancestor of modern Kra characters. | |||

== Government & Politics == | == Government & Politics == | ||

Latest revision as of 16:56, 27 February 2024

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Anachak Kang Hom Khao ອານາຈັກກາງຮົ່ມຂາວ (Kra) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: ສະບາສະມາ ສັງຂາບພຸດໂທ ສັງຂານສະມະກິ ວຸທິສາທິກາ "For the harmory of all the people, to prosper and to succeed" | |

| Anthem: Pheng Xat Kra "Hymn of the Kra" | |

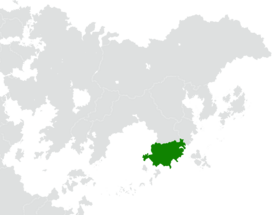

Location of Anachak Kang (green) in Ochran (grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Viangchan |

| Official languages | Kra |

| Recognised regional languages | Various local dialects |

| Ethnic groups (2022) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Kra |

| Government | Unitary parlimentary anocratic semi-consitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Chao Souk |

• Prince Regent | Khun Khanthavong |

• Prime Minister | Koa Cheruene |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,125,344 km2 (434,498 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 121,648,117 |

• Density | 108.1/km2 (280.0/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | $1.387 trillion |

• Per capita | $11,400 |

| Gini (2022) | 36.4 medium |

| HDI (2022) | high |

| Currency | Kip (₭) (KIP) |

| Time zone | (GST+8) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+7 ((GST+7)) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy CE |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +856 |

| Internet TLD | .ak |

Anachak Kang, officially Anachak Kang Hom Khao (Kra: ອານາຈັກກາງຮົ່ມຂາວ, lit. 'The Middle Kingdom and the White Parasol'), is a country in Southeast Ochran, situated in the Kra Peninsula, spanning 1,125,344 square kilometres (434,498 sq mi), with a population of 121,648,117. The country is bordered to the northeast by Seonko and shares maritime borders with Daobac to the south and Tsurushima (Kahei) to the east. Viangchan is the nation's capital and largest city.

Modern Kra traces its origins to a cradle of civilisation in the fertile Maena river basin in the Central Kra Plain. Their long occupation, initially in varying forms of hunter-gatherers, emerged into settled life 7,000 years ago, gradually evolving into the Maena Basin Civilisation of the third millennium BCE. By 1400 BCE, an archaic form of Sombhang, an Ochran-Malaio language, had diffused into the Kra peninsula from the southwest. Its evidence today is found in the hymns of the Samaphidthanya. Preserved by a resolutely vigilant oral tradition, the Samaphidthanya records the dawning of Sadthaism in Anachak Kang.

The Maena Basin Civilisation would help set the foundation of several regional cities that would turn into city-states and petty kingdoms. The semi-legendary kingdom of Muang Sua in the 21st century BC, the subsequent well-attested Kingdom of Lan Na and Chiang Mai, and the Kingdom of Lan Xang would help develop a unique regional political system known as the Aeuad. Kra writing, Kra classic literature and the Hundred Schools of Thought emerged during this period and influenced the inhabitants of the Kra peninsula for centuries to come. These Kra petty kingdoms would remain disunited until the third century BCE when Prince Fa Ngum of Viangchan's war of unification created the first Kra empire, the short-lived Fa dynasty. The more stable Baasac dynasty (206 BCE – 220CE) followed the collapse of the Fa, which established a model for nearly two millennia in which the Kra empire was one of the world's foremost economic powers. The empire expanded, fractured and reunified, was conquered and reestablished, absorbed foreign religions and ideas, and made world-leading scientific advances, such as the Five Great Inventions: mathematics, astronomy, the compass, paper, and printing. After centuries of disunion following the fall of the Baasac, the Ngoenyang (581 – 618) and Nanthavong (618 – 907) reunified the empire. During the time of the 3rd emperor of the Nanthavong dynasty, Nanthavong Khampong united the entirety of the Kra peninsula for the first time and introduced the first imperial examination system, creating a new civilian scholar-officials or literati class to replace the aristocratic military class of earlier dynasties. He also reintroduces old philosophical schools of thought such as Legalism* and Neo-Confucianism* to centralise power onto the monarch. However, his reforms would eventually become undone after a series of weak successive monarchs, allowing the Bayarid Empire to invade and occupy the nation successfully in 932. The Bayarid invasion established Anachak Kang as a semi-autonomous vassal state and compulsory ally of the Bayarids and its successor, the Great Khan's Court-in-Taizhou*. Anachak Kang would remain under the control of the Khan's Court until the Na dynasty (1358–1674) reestablished ethnic Kra control.

The Na dynasty peaked in the 17th century, until its destruction in the XXX–Kra War. Khampheng Kamchanh quickly reunified the fragmented territories and established the short-lived Khampheng dynasty (1678–1707). She was succeeded in 1707 by Kham Paxathipatai Siharath, the first monarch of the current Kham dynasty. Throughout the era of foreign imperialism in Ochran-Malaio, Anachak Kang was relatively untouched. However, the dynasty faced drastic changes in the world system; foreign intrusion, internal revolts, population growth, economic disruption, official corruption, and the reluctance of the scholar-official elites to change their traditionalist ways and mindset. With peace and prosperity, the population rose to some 90 million, but taxes and government revenues were fixed at a low rate, soon leading to the 1861 Fiscal Crisis. The Xiengthong Rebellion (1861-1875) and the Tha Khek Revolt (1875-1881) in Northern Anachak Kang led to the deaths of over 1 million people from famine, disease, and war. The Xriya Restoration in the 1890s brought vigorous reforms and the introduction of foreign military technology in the Self-Strengthening Movement. However, defeat in the Cross-Strait War in 1898 led to ratifying the Treaty of Hoabinh, which saw Anachak Kang further weakened at the turn of the century. The nation was able to reverse its decline with foreign aid, most notably from the Latin Empire. It participated in the Hanaki War (1927-1929*), allying with Pulau Keramat and Zanzali against the allies*.

Apart from a brief period of republicanism in the 1930s, Anachak Kang periodically alternated between democratic, monarchic and military rule. Since the 2000s, the country has been caught in the continual bitter political conflict between supporters and opponents of the royalist, the democratically elected government and the military elite, stemming from a failed coup attempt in 2003. The establishment of Anachak Kang's current constitution came from a compromise between the royalist and the nominally democratic government after the 2019 Kra general election, led by Prince Regent Kham Khanthavong and the moderate Prime Minister Koa Cheruene. Since 2019, Anachak Kang has been nominally a parliamentary constitutional monarchy; in practice, however, structural advantages in the constitution due to the compromise have resulted in a complex parliamentary anocratic semi-constitutional monarchy system balanced between the military, the democrats, and the monarchist.

Anachak Kang is a middle power* in global affairs and ranks relatively high on the Human Development Index. It is also classified as a newly industrialised economy, with manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism as leading sectors.

Etymology

Anachak Kang, officially Anachak Kang Hom Khao, was known by outsiders before the 1900s as Muang Kra (ເມືອງກະ) or Pathet Kra (ປະເທດກະ), both of which means 'The Country'. According to Oke Keothavong, the word Kra (ກະ) means 'people' or 'human being', his investigations show that some rural areas used the word "Kra" instead of the usual Kra word khon (ຄົນ) for people.

Kras still often refer to their country as Pathet Kra as a form of politeness; they also use Muang Kra as a more colloquial term or sometimes simply Kra. The word muang, archaically referring to a city-state, is commonly used to refer to a city or town as the centre of a region. Anachak Kang (Kra: ອານາຈັກກາງ) means 'middle kingdom' and Hom Khao (Kra: ຮົ່ມຂາວ) means 'white parasol'. Etymologically, its components are: -ana- (Pali āṇā 'authority, command, power', itself from the Sombhang आज्ञा, ājñā, of the same meaning) -chak (from Sombhang चक्र cakra- 'wheel', a symbol of power and rule); kang (Sombhang मध्यं madhya 'middle or central'). The name is thought to be developed when the Fa dynasty first united the disparate city-states and petty kingdoms and formed the first Kra empire in reference to its royal demesne (present-day Viangchan) as the centre of the Kra political entity. Subsequent dynasties then applied it to the area around Viangchan prefecture and then to the Kra Central Plain before being used as a synonym for the state in the present day. The name is also often used as a cultural concept to distinguish the Kra people from perceived "barbarians".

History

- For a chronological guide, see Timeline of Kra history

Prehistory

There is credible evidence of continuous human habitation in present-day Anachak Kang from 20,000 years ago to the present day. However, archaeological evidence suggests that early hominids inhabited the country 2 million years ago*. An ancient human skull was recovered in 2009 from Tam Pa Ling Cave* in the Annamite Mountains* in northern Anachak Kang with evidence of the use of fire; they have been dated to between 680,000 and 780,000 years ago. Stone artefacts, including Hoabinhian types, have been found at sites dating to the Late Pleistocene in northern Anachak Kang. Kra proto-writing existed in Xiangkhoang around 6600 BCE, at Houaphanh around 6000 BCE, at Bolikhamxai from 5800 to 5400 BCE, and in Hua Khong, dating from the 5th millennium BCE. Some scholars have suggested that the Xhiangkhoang symbols (7th millennium BCE) constituted the basis for the archaic form of Sombhang that was diffused into the peninsula in 1400 BCE.

Ancient Kra

By 6500 BCE, evidence for the domestication of foods, crops and animals, construction of permanent structures and storage of agricultural surplus appeared in Bokèo and other sites in what is now Luang Namtha province. These gradually developed into the Maena Basin Civilisation, the first urban culture in Southeast Ochran, which flourished from 2500 to 1900 BCE. The Maena Basic Civilisation centred around cities such as Luang Namtha (Old City), Luang Prabang, Muang Na, and Chiang Mai, relying on varied forms of subsistence and engaging in crafts production and regional trade. Burial jars and other kinds of sepulchres suggest a complex society in which bronze objects appeared around the time.

During the 2000–500 BCE, many cities of the Maena Basin Civilisation transitioned from the Chalcolithic culture to the Iron Age. The Phidthanya, the oldest scriptures associated with Sadthaism, were composed during this period. Historians have analysed these to posit a Phidthanyakra culture in the Central Kra Plain. Most historians also considered this period to have encompassed several waves of human migration into the peninsula from the north and south across the seas. A caste system, which created a hierarchy of priests, warriors, and free peasants, emerged during this period, dividing the Kra society into the traditional lineage roles that can still be seen today. The exclusion of the migrating "Outer Kra" became prominent during this period and labelled the migrators into the Central Kra Plain as impure and untouchable. On the outer fringe of the Central Kra Plain, archaeological evidence from this period suggests the evidence of a chiefdom stage of political organisation. Influenced by the civilisation of the Central Kra Plain, they are marked with a progression to sedentary life, as indicated by the large number of megalithic monuments dating from this period, as well as by nearby traces of agriculture, irrigation tanks, and craft traditions.

Early states and the Kingdom of Muang Sua

Oral traditions also preserved the cultural memory of the early Kra in the origin myths and practices of the Kra people. The cultural, linguistic, and political roots which highlight the commonality of these oral traditions can be traced to the Nithan Khun Borum (Kra: ນິທານຂຸນບູລົມ, lit. 'The Legend of Khun Borum'). The legend is central to these origin stories and forms the introduction to the Phongsavadan (Kra: ພົງສະຫວັນ, lit 'Court Chronicles'), which are read aloud during auspicious occasions and festivals. Throughout the history of Anachak Kang, the legitimacy of the various dynasties was tied to their relation to the historical dynasty of Khun Lo, the legendary King of Lan Na and the son of Khun Borum.

According to the Nithan Khun Borum, the Kingdom of Muang Sua emerged around 2100 BCE. The kingdom marked the beginning of Anachak Kang's political system based on the hereditary leadership of a muang and the vassalised polities under it as a centre of domination. Historians describe this unique political concept as the Aeuad, where the central state distributed political power amongst their vassals, and local authorities were more important than the central leadership.

Historians considered Muang Sua mythical until modern scientific excavations found early Bronze Age sites at present-day Muang Sua in 1959, giving the region its namesake. It remains unclear whether these sites are the remains of the Muang Sua or another culture from the same period. The succeeding Kingdom of Lan Na and the Kingdom of Chiang Mai is the earliest confirmed by contemporary records. Lan Na and Chiang Mai ruled much of the plains surrounding the Maena River from the 17th to the 11th century BCE. Their oracle bone script (from c. 1500 BCE) represents the oldest form of Kra writing yet found and is a direct ancestor of modern Kra characters.