Torédo Doctrine: Difference between revisions

ContraViper (talk | contribs) |

m (Fixed formatting) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

The doctrine was conceived during the middle-height of the Red Insurgency, following the 1984 Coup in [[Cuscatlan]]. The "People's Republic of Tirmeno", de-facto run by the leftist insurgent group Marçon de Rouje, was now mostly cut off from land-based supply - not including clandestine routes and "drug smuggling corridors" - and needed port or air-based cargo to continue to receive weapons, ammo and medical supplies. However, the actual "policing action" on the ground was going poorly in Inyursta, with MdR groups popping back up usually within the same year of an area being "sanitized" of insurgents. Torédo and his contemporaries feared the war would be "indefinite" if the supply base in Tirméno was not enclosed and severed. It was therefore conceived that instead of trying to leverage its air and naval advantage "like a bull in a wine cellar" against insurgents, Inyursta should instead leverage its advantage to deny access to foreign suppliers of MdR. | |||

At the time, Generàle Torédo did not name the doctrine after himself, but rather called it "Plán d'Anacònda Grande" (Great Anaconda Plan) - an attempt to "constrict" the territory of Tirméno. | At the time, Generàle Torédo did not name the doctrine after himself, but rather called it "Plán d'Anacònda Grande" (Great Anaconda Plan) - an attempt to "constrict" the territory of Tirméno. | ||

| Line 38: | Line 40: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

==Criticism== | ==Criticism== | ||

A number of criticisms have been levied at Torédo Doctrine. | A number of criticisms have been levied at Torédo Doctrine. <br/> | ||

First, the risk of direct conflict - even if limited and generally fought with air/sea assets, is more costly than fighting even a long, drawn out proxy war. | First, the risk of direct conflict - even if limited and generally fought with air/sea assets, is more costly than fighting even a long, drawn out proxy war.<br/> | ||

Second, that a state can never truly be confident if its opposition is in fact rational or irrational, thus leading to increased risk of catastrophic escalation. | Second, that a state can never truly be confident if its opposition is in fact rational or irrational, thus leading to increased risk of catastrophic escalation.<br/> | ||

Third, the use of Torédo Doctrine simply encourages craftier ways for opponents to supply their own proxy forces. Many analysts asses that hypothetical enemies would simply carry military cargo disguised as civilian, thus forcing a doctrine user to engage civilian targets. | |||

Additionally, many military theorists will argue that Torédo did not recommend against avoiding ALL proxy conflicts inherently, rather those which are "unwinnable" or near-unwinnable (or simply where the cost of engaging the supplier is less than the cost of waging a proxy conflict). While most Inyurstan military scholars agree that proxy conflicts are generally less favorable than direct conflicts, there still exists a margin of proxy conflicts where it is "easier" or more reward-per-risk to keep the conflict in its proxy phase; and such conflicts should be exploited and not escalated. In summary, such scholars would argue that Torédo Doctrine exists not as a rebuke of ALL proxy conflicts, but rather a standard means to avoid those which are unfavorable. | |||

===Modern Defense=== | |||

Proponents of a modern Torédo Doctrine have argued that recent advancements in area-denial capabilities have made the doctrine even more relevant. For example, at the time all air or sea engagements would have taken place with unguided or early-generation precision-guided munitions which would have caused high attrition rates. More recently, targets can be engaged at much longer ranges with much lower personnel or platform attrition rates (albeit at a greater price-tag per-munition), thus making such a direct confrontation less unappealing. Additionally, such modern advancements allow a disproportionate force ratio against enemy naval or air forces, meaning that the would-be supplier would be undertaking significantly greater risk and loss than the attacker. | |||

Latest revision as of 23:25, 4 October 2024

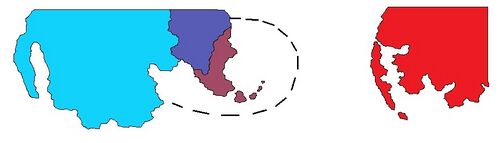

Torédo Doctrine is one of several strategic doctrines practiced by the armed forces of Inyursta. Specifically, Torédo Doctrine is used as a means of mitigating, avoiding or escalating proxy conflicts. It is named for Generàle Ferdinand Torédo, successor to Enrique Javez, who came to the conclusion that the Red Insurgency would be near-infinite if supplies to Marçon de Rouje were not indefinitely severed.

History

The doctrine was conceived during the middle-height of the Red Insurgency, following the 1984 Coup in Cuscatlan. The "People's Republic of Tirmeno", de-facto run by the leftist insurgent group Marçon de Rouje, was now mostly cut off from land-based supply - not including clandestine routes and "drug smuggling corridors" - and needed port or air-based cargo to continue to receive weapons, ammo and medical supplies. However, the actual "policing action" on the ground was going poorly in Inyursta, with MdR groups popping back up usually within the same year of an area being "sanitized" of insurgents. Torédo and his contemporaries feared the war would be "indefinite" if the supply base in Tirméno was not enclosed and severed. It was therefore conceived that instead of trying to leverage its air and naval advantage "like a bull in a wine cellar" against insurgents, Inyursta should instead leverage its advantage to deny access to foreign suppliers of MdR.

At the time, Generàle Torédo did not name the doctrine after himself, but rather called it "Plán d'Anacònda Grande" (Great Anaconda Plan) - an attempt to "constrict" the territory of Tirméno.

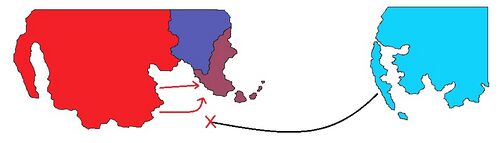

Both critics and supporters to this day argue if Torédo Doctrine helped lead to the 1986 Guerrocan War, where even some supporters may admit that the actions taken against North Guerrocan shipping may have contributed to the conflict and even some detractors admit that Guerroca was likely to blitz the peninsula regardless.

Assumptions

A number of assumptions must be true for Torédo Doctrine to be applied successfully.

- The attacker is either closer to the conflict zone than the opposing supplier OR possesses a significant advantage in power projection and range of military assets

- Parity or near-parity (advantage attacker) between the attacker and opposing supplier OR where the range distance causes parity

- Rational actors, where the chances of direct intervention/assault onto the attacker's homeland is minimized and threat of WMD use is either non-credible or approaching zero

Null Assumptions

Torédo Doctrine cannot be successfully applied when the following assumptions are true:

- Situations where the conflict is closer to the opposing supplier's homeland or permanent and significant base of operations than to the attacker OR the proxy force is directly fighting against the opposing supplier

- Significantly stronger forces, wherein the opposing supplier can functionally defeat the attacker in >50% of engagements in the supply chain process OR holds a probable chance of victory in the attacker's homeland

- Irrational actors, wherein there is a very real chance the opposing supplier would resort to some form of WMD attack or other mass-casualty event

Criticism

A number of criticisms have been levied at Torédo Doctrine.

First, the risk of direct conflict - even if limited and generally fought with air/sea assets, is more costly than fighting even a long, drawn out proxy war.

Second, that a state can never truly be confident if its opposition is in fact rational or irrational, thus leading to increased risk of catastrophic escalation.

Third, the use of Torédo Doctrine simply encourages craftier ways for opponents to supply their own proxy forces. Many analysts asses that hypothetical enemies would simply carry military cargo disguised as civilian, thus forcing a doctrine user to engage civilian targets.

Additionally, many military theorists will argue that Torédo did not recommend against avoiding ALL proxy conflicts inherently, rather those which are "unwinnable" or near-unwinnable (or simply where the cost of engaging the supplier is less than the cost of waging a proxy conflict). While most Inyurstan military scholars agree that proxy conflicts are generally less favorable than direct conflicts, there still exists a margin of proxy conflicts where it is "easier" or more reward-per-risk to keep the conflict in its proxy phase; and such conflicts should be exploited and not escalated. In summary, such scholars would argue that Torédo Doctrine exists not as a rebuke of ALL proxy conflicts, but rather a standard means to avoid those which are unfavorable.

Modern Defense

Proponents of a modern Torédo Doctrine have argued that recent advancements in area-denial capabilities have made the doctrine even more relevant. For example, at the time all air or sea engagements would have taken place with unguided or early-generation precision-guided munitions which would have caused high attrition rates. More recently, targets can be engaged at much longer ranges with much lower personnel or platform attrition rates (albeit at a greater price-tag per-munition), thus making such a direct confrontation less unappealing. Additionally, such modern advancements allow a disproportionate force ratio against enemy naval or air forces, meaning that the would-be supplier would be undertaking significantly greater risk and loss than the attacker.