|

|

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 17: |

Line 17: |

| |nickname = | | |nickname = |

| |motto = | | |motto = |

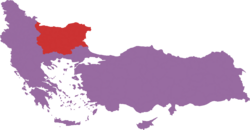

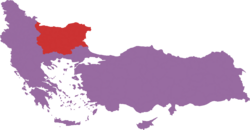

| |image_map = | | |image_map = File:Mappa 05 - 03 - Moesia 01 trasp.png |

| |map_alt = | | |map_alt = |

| |map_caption = | | |map_caption = Moesia within the Empire |

| |pushpin_map = | | |pushpin_map = |

| |pushpin_map_alt = | | |pushpin_map_alt = |

| Line 36: |

Line 36: |

| |subdivision_type3 = | | |subdivision_type3 = |

| |subdivision_name3 = | | |subdivision_name3 = |

| |established_title = Established | | |established_title = Established as Catepanate of Rumelia |

| |established_date = 1756 | | |established_date = 1756 |

| |founder = Alexios VII | | |founder = Alexios VII |

| Line 111: |

Line 111: |

| }} | | }} |

|

| |

|

| '''Moesia''', (Greek: Μοισία ''Moisía''; Bulgarian: Мизия ''Miziya'') officially the '''Province of Bulgaria''' (Greek: Περιφέρεια Μοισίας ''Periféreia Moisías''; Bulgarian: Провинция Мизия ''Provintsiya Miziya'') is a Province of the [[Byzatium|Byzantine Empire]] in Southeast Europe. Located west of the Black Sea and south of the Danube river, Moesia is bordered by Romania to the north. It covers a territory of {{convert|110994|km2}} and is the 4th largest Province in the Empire. [[wikipedia:Sofia|Serdica]] is the Province's capital and largest city; other major cities include [[wikipedia:Burgas|Pyrgos]], [[wikipedia:Plovdiv|Philippopolis]], and Varna. | | '''Moesia''', (Greek: Μοισία ''Moisía''; Bulgarian: Мизия ''Miziya'') officially the '''Province of Moesia''' (Greek: Περιφέρεια Μοισίας ''Periféreia Moisías''; Bulgarian: Провинция Мизия ''Provintsiya Miziya'') is a Province of the [[Byzatium|Byzantine Empire]] in Southeast Europe. Located west of the Black Sea and south of the Danube river, Moesia is bordered by Romania to the north. It covers a territory of {{convert|110994|km2}} and is the 4th largest Province in the Empire. [[wikipedia:Sofia|Serdica]] is the Province's capital and largest city; other major cities include [[wikipedia:Burgas|Pyrgos]], [[wikipedia:Plovdiv|Philippopolis]], and Varna. |

|

| |

|

| One of the earliest societies in the lands of modern-day Bulgaria was the Karanovo culture (6,500 BC). In the 6th to 3rd century BC, the region was a battleground for ancient Thracians, Persians, Celts and Ancient Macedonians; stability came when the Roman Empire conquered the region in AD 45. After the Roman state splintered, tribal invasions in the region resumed. Around the 6th century, these territories were settled by the early Slavs. The Bulgars, led by Asparuh of Bulgaria, attacked from the lands of Old Great Bulgaria and permanently invaded the Balkans in the late 7th century. They established the First Bulgarian Empire, victoriously recognised by treaty in 681 AD by the Byzantine Empire. It dominated most of the Balkans and significantly influenced Slavic cultures by developing the Cyrillic script. The First Bulgarian Empire lasted until the early 11th century, when Byzantine emperor Basil II conquered and dismantled it. A successful Bulgarian revolt in 1185 established a Second Bulgarian Empire, which reached its apex under Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria (1218–1241). After numerous exhausting wars and feudal strife, the empire disintegrated and in 1396 fell under Ottoman rule for nearly three centuries. | | One of the earliest societies in the lands of modern-day Moesia was the Karanovo culture (6,500 BC). In the 6th to 3rd century BC, the region was a battleground for ancient Thracians, Persians, Celts and Ancient Macedonians; stability came when the Roman Empire conquered the region in AD 45. After the Roman state splintered, tribal invasions in the region resumed. Around the 6th century, these territories were settled by the early Slavs. The Bulgars, led by Asparuh of Bulgaria, attacked from the lands of Old Great Bulgaria and permanently invaded the Balkans in the late 7th century. They established the First Bulgarian Empire, victoriously recognised by treaty in 681 AD by the Byzantine Empire. It dominated most of the Balkans and significantly influenced Slavic cultures by developing the Cyrillic script. The First Bulgarian Empire lasted until the early 11th century, when Byzantine emperor Basil II conquered and dismantled it. A successful Bulgarian revolt in 1185 established a Second Bulgarian Empire, which reached its apex under Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria (1218–1241). After numerous exhausting wars and feudal strife, the empire disintegrated and in 1396 fell under Ottoman rule for nearly three centuries. |

|

| |

|

| After the end of the Byzantine civil war in 1524, the Byzantine Empire shifted its focus toward internal stability and regional influence. Emperor Michael XI, cementing his rule, prioritized the consolidation of Byzantine power in the Ottoman Balkans. Key military leader John Palaiologos played a crucial role in securing control over strategic territories. In 1527, Byzantine forces successfully besieged and reclaimed Adrianople, establishing it as a strategic center. After nearly thirty years of war, in 1556, Byzantine conquered Achrida, solidifying control over crucial trade routes. Sporadic fighting and limited campaigns lasted until 1602 when Emperor John IX entered in Episkion. | | After the end of the Byzantine civil war in 1524, the Byzantine Empire shifted its focus toward internal stability and regional influence. Emperor Michael XI, cementing his rule, prioritized the consolidation of Byzantine power in the Ottoman Balkans. Key military leader John Palaiologos played a crucial role in securing control over strategic territories. In 1527, Byzantine forces successfully besieged and reclaimed Adrianople, establishing it as a strategic center. After nearly thirty years of war, in 1556, Byzantine conquered Achrida, solidifying control over crucial trade routes. Sporadic fighting and limited campaigns lasted until 1602 when Emperor John IX entered in Episkion. |

| Line 120: |

Line 120: |

| The most notable topographical features of the Province are the Danubian Plain, the Balkan Mountains, the Thracian Plain, and the Rhodope massif. The southern edge of the Danubian Plain slopes upward into the foothills of the Balkans, while the Danube defines the border with Romania. The Thracian Plain is roughly triangular, beginning southeast of Serdica and broadening as it reaches the ìBlack Sea coast. | | The most notable topographical features of the Province are the Danubian Plain, the Balkan Mountains, the Thracian Plain, and the Rhodope massif. The southern edge of the Danubian Plain slopes upward into the foothills of the Balkans, while the Danube defines the border with Romania. The Thracian Plain is roughly triangular, beginning southeast of Serdica and broadening as it reaches the ìBlack Sea coast. |

|

| |

|

| The Balkan mountains run laterally through the middle of the province from west to east. The mountainous southwest has two distinct lpine type ranges— Rila and Pirin, which border the lower but more extensive Rhodope Mountains to the east, and various medium altitude mountains to west, northwest and south, like Vitosha, Osogovo and Belasitsa. Musala, at {{convert|2925|m|ft|0}}, is the highest point in both Bulgaria and the Balkans. The Black Sea coast is the country's lowest point. Plains occupy about one third of the territory, while plateaux and hills occupy 41%. Most rivers are short and with low water levels. The longest river located solely in Moesian territory, the Iskar, has a length of {{convert|368|km|0}}. The Strymónas and the Evros are two major rivers in the south. | | The Balkan mountains run laterally through the middle of the province from west to east. The mountainous southwest has two distinct lpine type ranges— Rila and Pirin, which border the lower but more extensive Rhodope Mountains to the east, and various medium altitude mountains to west, northwest and south, like Vitosha, Osogovo and Belasitsa. Musala, at {{convert|2925|m|ft|0}}, is the highest point in both Moesia and the Balkans. The Black Sea coast is the country's lowest point. Plains occupy about one third of the territory, while plateaux and hills occupy 41%. Most rivers are short and with low water levels. The longest river located solely in Moesian territory, the Iskar, has a length of {{convert|368|km|0}}. The Strymónas and the Evros are two major rivers in the south. |

|

| |

|

| === Climate === | | === Climate === |

| Moesia has a varied and changeable climate, which results from being positioned at the meeting point of the Mediterranean, Oceanic and Continental air masses combined with the barrier effect of its mountains. Northern Bulgaria averages {{convert|1|C-change|1}} cooler, and registers {{convert|200|mm|1}} more precipitation, than the regions south of the Balkan mountains. Temperature amplitudes vary significantly in different areas. The lowest recorded temperature is {{cvt|-38.3|°C|°F|1}}, while the highest is {{cvt|45.2|°C|°F|1}}. Precipitation averages about {{convert|630|mm|in|1}} per year, and varies from {{convert|500|mm|1}} in [[wikipedia:Dobrudja|Kalí Chóra]] to more than {{convert|2500|mm|1}} in the mountains. Continental air masses bring significant amounts of snowfall during winter. | | Moesia has a varied and changeable climate, which results from being positioned at the meeting point of the Mediterranean, Oceanic and Continental air masses combined with the barrier effect of its mountains. Northern Moesia averages {{convert|1|C-change|1}} cooler, and registers {{convert|200|mm|1}} more precipitation, than the regions south of the Balkan mountains. Temperature amplitudes vary significantly in different areas. The lowest recorded temperature is {{cvt|-38.3|°C|°F|1}}, while the highest is {{cvt|45.2|°C|°F|1}}. Precipitation averages about {{convert|630|mm|in|1}} per year, and varies from {{convert|500|mm|1}} in [[wikipedia:Dobrudja|Kalí Chóra]] to more than {{convert|2500|mm|1}} in the mountains. Continental air masses bring significant amounts of snowfall during winter. |

|

| |

|

| [[File:Koppen-Geiger Map BGR present.svg|thumb|left|300px|alt=Köppen climate types of Bulgaria|Köppen climate types of Moesia]] | | [[File:Koppen-Geiger Map BGR present.svg|thumb|left|300px|alt=Köppen climate types of Moesia|Köppen climate types of Moesia]] |

| Considering its relatively small area, Moesia has variable and complex climate. The province occupies the southernmost part of the continental climatic zone, with small areas in the south falling within the Mediterranean climatic zone. The continental zone is predominant, because continental air masses flow easily into the unobstructed Danubian Plain. The continental influence, stronger during the winter, produces abundant snowfall; the Mediterranean influence increases during the second half of summer and produces hot and dry weather. Moesia is subdivided into five climatic zones: continental zone (Danubian Plain, Pre-Balkan and the higher valleys of the Transitional geomorphological region); transitional zone (Upper Thracian Plain, most of the Struma and Mesta valleys, the lower Sub-Balkan valleys); continental-Mediterranean zone (the southernmost areas of the Struma and Mesta valleys, the eastern Rhodope Mountains, Sakar and Strandzha); Black Sea zone along the coastline with an average length of 30–40 km inland; and alpine zone in the mountains above 1000 m altitude (central Balkan Mountains, Rila, Pirin, Vitosha, western Rhodope Mountains, etc.). | | Considering its relatively small area, Moesia has variable and complex climate. The province occupies the southernmost part of the continental climatic zone, with small areas in the south falling within the Mediterranean climatic zone. The continental zone is predominant, because continental air masses flow easily into the unobstructed Danubian Plain. The continental influence, stronger during the winter, produces abundant snowfall; the Mediterranean influence increases during the second half of summer and produces hot and dry weather. Moesia is subdivided into five climatic zones: continental zone (Danubian Plain, Pre-Balkan and the higher valleys of the Transitional geomorphological region); transitional zone (Upper Thracian Plain, most of the Struma and Mesta valleys, the lower Sub-Balkan valleys); continental-Mediterranean zone (the southernmost areas of the Struma and Mesta valleys, the eastern Rhodope Mountains, Sakar and Strandzha); Black Sea zone along the coastline with an average length of 30–40 km inland; and alpine zone in the mountains above 1000 m altitude (central Balkan Mountains, Rila, Pirin, Vitosha, western Rhodope Mountains, etc.). |

|

| |

|

| === Administrative divisions === | | == Demographics == |

| Moesia is subdivided into 28 Eparchies, including the Metropolitan Eparchy of Serdica city. All areas take their names from their respective capital cities. The Eparchies are subdivided into over 1,000 municipalities. Municipalities are run by Prokathemenoi, who are elected to four-year terms, and by directly elected municipal councils. Within the framework of the Byzantine legal system, Moesia has an highly centralised political organisation, where Eparchies, Archontates, Demos, and municipalities are heavily dependent on it for funding. | | According to the provincial government's official 2022 estimate, the population of Moesia consists of 6,447,710 people. The majority of the population, 62.5%, reside in urban areas. As of 2019, Serdica is the most populated urban centre with 1,241,675 people, followed by Philippopolis, Varna, Pyrgos and Rousopolis. Bulgarian Slavs are the main ethnic group and constitute 63.6% of the population. Greeks account for the 35.1% (mostly in the south) and some 40 smaller minorities account for 1.3%. Population density is 55-60 per square kilometre (ultimo 2023). |

| | |

| | == Administrative divisions == |

| | Moesia was established in 1965 with the merger of two Provinces: Thrace (comprising the Rhodopes and the Thracian Plain), and Bóreia Sýnora (comprising the Balkans and the Danubian Plain). Blagoevgrad Eparchy was transferred from Macedonia to Moesia in 1969 in order to unify economic governance subdivision and civil administration bodies. This territory still maintains significant cultural ties with its former Province.<br> |

| | Modern-day Moesia is subdivided into 28 Eparchies, including the Metropolitan Eparchy of Serdica city. All areas take their names from their respective capital cities. The Eparchies are subdivided into over 1,000 municipalities. Municipalities are run by Prokathemenoi, who are elected to four-year terms, and by directly elected municipal councils. Within the framework of the Byzantine legal system, Moesia has an highly centralised political organisation, where Eparchies, Archontates, Demos, and municipalities are heavily dependent on it for funding. |

|

| |

|

| {| style="margin:auto;" cellpadding="10" | | {| style="margin:auto;" cellpadding="10" |

| |- | | |- |

| | | | | [[File:Bulgaria Administrative Provinces.png|250px]] Eparchies in Moesia |

| |style="font-size:90%;font-weight:bold;"| | | |style="font-size:90%;font-weight:bold;"| |

| {{col-begin|width=auto}} | | {{col-begin|width=auto}} |

| {{col-break|gap=2em}} | | {{col-break|gap=2em}} |

| {{ordered list|start=1|[[Blagoevgrad Province|Blagoevgrad]]|[[Burgas Province|Burgas]]|[[Dobrich Province|Dobrich]]|[[Gabrovo Province|Gabrovo]]|[[Haskovo Province|Haskovo]]|[[Kardzhali Province|Kardzhali]]|[[Kyustendil Province|Kyustendil]]|[[Lovech Province|Lovech]]|[[Montana Province|Montana]]}} | | {{ordered list|start=10901|[[wikipedia:Kardzhali|Achridos]]|[[wikipedia:Veliko Tarnovo|Ankapolis]]|[[wikipedia:Kyustendil|Belebousda]]|[[wikipedia:Blagoevgrad|Blagoevgrad]]|[[wikipedia:Lovech|Chisaria]]|[[wikipedia:Silistra|Dristra]]|[[wikipedia:Dobrich|Dobrich]]|[[wikipedia:Razgrad|Ezarpolis]]|[[wikipedia:Gabrovo|Gabrovo]]}} |

| {{col-break|gap=2em}} | | {{col-break|gap=2em}} |

| {{ordered list|start=10|[[Pazardzhik Province|Pazardzhik]]|[[Pernik Province|Pernik]]|[[Pleven Province|Pleven]]|[[Plovdiv Province|Plovdiv]]|[[Razgrad Province|Razgrad]]|[[Ruse Province|Ruse]]|[[Shumen Province|Shumen]]|[[Silistra Province|Silistra]]|[[Sliven Province|Sliven]]}} | | {{ordered list|start=10910|[[wikipedia:Pernik|Kókkino Kástro]]|[[wikipedia:Montana, Bulgaria|Kutlovitsa]]|[[wikipedia:Stara Zagora|Irenopolis]]|[[wikipedia:Haskovo|Marsa]]|[[wikipedia:Pazardzhik|Pazard]]|[[wikipedia:Plovdiv|Philippopolis]]|[[wikipedia:Pleven|Pleven]]|[[wikipedia:Burgas|Pyrgos]]| |

| | [[wikipedia:Ruse, Bulgaria|Rousopolis]]}} |

| {{col-break|gap=2em}} | | {{col-break|gap=2em}} |

| {{ordered list|start=19|[[Smolyan Province|Smolyan]]|[[Sofia Province]]|[[Stara Zagora Province|Stara Zagora]]|[[Targovishte Province|Targovishte]]|[[Varna Province|Varna]]|[[Veliko Tarnovo Province|Veliko Tarnovo]]|[[Vidin Province|Vidin]]|[[Vratsa Province|Vratsa]]|[[Yambol Province|Yambol]]}} | | {{ordered list|start=10919|[[wikipedia:Sliven|Selymnos]]|[[wikipedia:Sofia Province|Serdica]]|[[wikipedia:Sofia City Province|Serdica city]]|[[wikipedia:Shumen|Šimeonis]]|[[wikipedia:Smolyan|Smolyan]]|[[wikipedia:Targovishte|Targoviste]]|[[wikipedia:Varna, Bulgaria|Varna]]|[[wikipedia:Vidin|Vidin]]|[[wikipedia:Vratsa|Vratsa]]|[[wikipedia:Yambol|Yambol]]}} |

| {{col-end}} | | {{col-end}} |

| |} | | |} |

|

| |

|

| |

| [[wikipedia:Kardzhali|Achridos]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Kyustendil|Belebousda]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Blagoevgrad|Blagoevgrad]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Lovech|Chisaria]]

| |

|

| |

| [[wikipedia:Silistra|Dristra]]

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| [[wikipedia:Dobrich|Dobrich]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Razgrad|Ezarpolis]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Gabrovo|Gabrovo]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Pernik|Kókkino Kástro]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Montana, Bulgaria|Kutlovitsa]]

| |

|

| |

| [[wikipedia:Haskovo|Marsa]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Pazardzhik|Pazard]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Plovdiv|Philippopolis]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Pleven|Pleven]]

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| [[wikipedia:Burgas|Pyrgos]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Ruse, Bulgaria|Rousopolis]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Shumen|Šimeonis]]

| |

| [[wikpedia:Varna, Bulgaria|Varna]]

| |

| [[wikipedia:Vidin|Vidin]]

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| == Economy == | | == Economy == |

| {{Main|Economy of Bulgaria}}

| | Moesia has an open, high-income range market economy where the private sector accounts for more than 65% of GDP. From a largely agricultural province with a predominantly rural population in 1948, by the 1980s Moesia had transformed into an industrial economy, with scientific and technological research at the top of its budgetary expenditure priorities. |

| [[File:Economic Growth in Bulgaria.gif|thumb|upright=2|alt=Graph showing GDP and unemployment|Economic growth (green) and unemployment (blue) statistics since 2001]]

| |

| Bulgaria has an open, [[Economy of Bulgaria|high-income]] range [[market economy]] where the private sector accounts for more than 70% of [[Gross domestic product|GDP]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 |title=World Bank Country and Lending Groups |year=2018 |publisher=The World Bank Group |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180111190936/https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 |archive-date=11 January 2018 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.usaid.gov/pubs/cbj2002/ee/bg/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110710020431/http://www.usaid.gov/pubs/cbj2002/ee/bg/ |archive-date=10 July 2011 |title=Bulgaria Overview |year=2002 |publisher=[[USAID]] |access-date=2 November 2011}}</ref> From a largely agricultural country with a predominantly rural population in 1948, by the 1980s Bulgaria had transformed into an industrial economy, with scientific and technological research at the top of its budgetary expenditure priorities.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Bulgaria/Late-communist-rule |title=Bulgaria – Late Communist rule |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |first=John D. |last=Bell |access-date=28 July 2018 |quote=Bulgaria gave the highest priority to scientific and technological advancement and the development of trade skills appropriate to an industrial state. In 1948 approximately 80 percent of the population drew their living from the soil, but by 1988 less than one-fifth of the labour force was engaged in agriculture, with the rest concentrated in industry and the service sector. |archive-date=12 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512223141/https://www.britannica.com/place/Bulgaria/Late-communist-rule |url-status=live }}</ref> The loss of [[COMECON]] markets in 1990 and the subsequent "[[Shock therapy (economics)|shock therapy]]" of the [[Planned economy|planned system]] caused a steep decline in industrial and agricultural production, ultimately followed by an economic collapse in 1997.<ref name="Economies">{{cite web |url=http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/een/005/article_4326_en.htm |title=The economies of Bulgaria and Romania |publisher=[[European Commission]] |date=January 2007 |access-date=20 December 2011 |archive-date=25 January 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120125014952/http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/een/005/article_4326_en.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=OECD Economic Surveys: Bulgaria |publisher=[[OECD]] |year=1999 |page=24 |isbn=9789264167735 |url=https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-economic-surveys-bulgaria-1999_eco_surveys-bgr-1999-en#page24 |quote=The previous 1997 Economic Survey of Bulgaria documented how a combination of difficult initial conditions, delays in structural reforms, ... culminated in the economic crisis of 1996–97. |access-date=4 October 2018 |archive-date=19 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220419163006/https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-economic-surveys-bulgaria-1999_eco_surveys-bgr-1999-en#page24 |url-status=live }}</ref> The economy largely recovered during a period of rapid growth several years later,<ref name="Economies" /> but the average salary of 2,072 leva ($1,142) per month remains the lowest in the EU.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.investor.bg/a/517-pazar-na-truda/384379-srednata-zaplata-v-balgariya-v-kraya-na-septemvri-stigna-2072-lv |title=Средната заплата в България в края на септември стигна 2072 лв}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| A [[balanced budget]] was achieved in 2003 and the country began running a [[budget surplus|surplus]] the following year.<ref name="OECD1">{{cite journal |last1=Hawkesworth |first1=Ian |title=Budgeting in Bulgaria |journal=OECD Journal on Budgeting |date=2009 |issue=3/2009 |page=137 |url=https://www.oecd.org/countries/bulgaria/46051594.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://www.oecd.org/countries/bulgaria/46051594.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |access-date=6 August 2018}}</ref> Expenditures amounted to $21.15 billion and revenues were $21.67 billion in 2017.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2056.html#bu |title=Field listing: Budget |website=[[The World Factbook]] |publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]] |access-date=16 July 2018 |archive-date=6 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180706234818/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2056.html#bu |url-status=dead}}</ref> Most government spending on institutions is earmarked for security. The ministries of defence, the interior and justice are allocated the largest share of the annual government budget, whereas those responsible for the environment, tourism and energy receive the least funding.<ref name="2018budget">{{cite web |url=https://www.capital.bg/politika_i_ikonomika/bulgaria/2017/10/23/3064620_bjudjet_2018_poveche_za_zaplati_zdrave_i_pensii/ |script-title=bg:Бюджет 2018: Повече за заплати, здраве и пенсии |trans-title=2018 Budget: More for salaries, health and pensions |publisher=Kapital Daily |first=Vera |last=Denizova |date=23 October 2017 |access-date=16 July 2018 |language=bg |archive-date=12 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512223215/https://www.capital.bg/politika_i_ikonomika/bulgaria/2017/10/23/3064620_bjudjet_2018_poveche_za_zaplati_zdrave_i_pensii/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Taxes form the bulk of government revenue<ref name="2018budget" /> at 30% of GDP.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2221.html#bu |title=Field listing: Taxes and other revenue |website=[[The World Factbook]] |publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]] |access-date=16 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180716223948/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2221.html#bu |archive-date=16 July 2018 |url-status=dead}}</ref> Bulgaria has some of the lowest corporate income [[Tax rates in Europe|tax rates in the EU]] at a flat 10% rate.<ref>{{cite web |title=These are the 29 countries with the world's lowest levels of tax |url=http://uk.businessinsider.com/wef-countries-with-the-lowest-levels-of-tax-on-earth-2016-3/#29-bulgaria-27--corporate-taxes-in-bulgaria-are-just-10-the-same-as-the-maximum-possible-income-tax-charged-to-individuals-in-the-country-that-numbers-is-one-of-the-five-lowest-in-europe-1 |website=Business Insider |date=15 March 2016 |access-date=16 July 2018 |archive-date=8 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190108052815/http://uk.businessinsider.com/wef-countries-with-the-lowest-levels-of-tax-on-earth-2016-3/#29-bulgaria-27--corporate-taxes-in-bulgaria-are-just-10-the-same-as-the-maximum-possible-income-tax-charged-to-individuals-in-the-country-that-numbers-is-one-of-the-five-lowest-in-europe-1 |url-status=live }}</ref> The tax system is two-tier. [[Value added tax]], [[excise duties]], corporate and personal income tax are national, whereas real estate, inheritance, and vehicle taxes are levied by local authorities.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.minfin.bg/en/774 |title=Structure of Bulgarian Tax System |publisher=Ministry of Finance of Bulgaria |access-date=16 July 2018 |archive-date=12 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512223234/https://www.minfin.bg/en/774 |url-status=live }}</ref> Strong economic performance in the early 2000s reduced [[government debt]] from 79.6% in 1998 to 14.1% in 2008.<ref name="OECD1" /> It has since increased to 22.6% of GDP by 2022, but remains the second lowest in the EU.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.nsi.bg/bg/content/11476/%D0%B1%D1%80%D1%83%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BD-%D0%B4%D1%8A%D1%80%D0%B6%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%BD-%D0%B4%D1%8A%D0%BB%D0%B3 |title=Брутен държавен дълг |website=www.nsi.bg |access-date=10 February 2024 |archive-date=6 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231206003509/https://www.nsi.bg/bg/content/11476/%D0%B1%D1%80%D1%83%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BD-%D0%B4%D1%8A%D1%80%D0%B6%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%BD-%D0%B4%D1%8A%D0%BB%D0%B3 |url-status=live }}</ref>

| |

| [[File:Business Park Sofia view 2.jpg|left|thumb|A business park in Sofia, the nation's largest economic hub]]

| |

| [[File:GBO 0949.jpg|left|thumb|An electronics factory in [[Trakia Economic Zone]] near [[Plovdiv]]]]

| |

| The [[Yugozapaden]] [[First-level NUTS of the European Union|planning area]] is the most developed region with a [[per capita]] gross domestic product ([[Purchasing power parity|PPP]]) of $29,816 in 2018.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tgs00005&plugin=1 |title=Regional gross domestic product (PPS per inhabitant), by NUTS 2 regions |publisher=Eurostat |access-date=12 March 2017 |archive-date=29 March 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170329141653/http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tgs00005&plugin=1 |url-status=live }}</ref> It includes the capital city and the surrounding [[Sofia Province]], which alone generate 42% of national gross domestic product despite hosting only 22% of the population.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nsi.bg/bg/content/2215/%D0%B1%D0%B2%D0%BF-%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B3%D0%B8%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%BD%D0%BE-%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B2%D0%BE |script-title=bg:БВП – регионално ниво |trans-title=GDP – regional level |publisher=National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria |access-date=22 July 2018 |language=bg |archive-date=20 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180720051916/http://www.nsi.bg/bg/content/2215/%D0%B1%D0%B2%D0%BF-%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B3%D0%B8%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%BD%D0%BE-%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B2%D0%BE |url-status=live }}</ref>{{sfn|NSI Census data|2017}} [[GDP]] per capita (in PPS) and the cost of living in 2019 stood at 53 and 52.8% of the EU average (100%), respectively.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tec00114 |title=GDP per capita in PPS |publisher=Eurostat |website=ec.europa.eu/eurostat |access-date=19 June 2020 |archive-date=9 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210109171045/https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tec00114 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tec00120 |title=Comparative price levels |publisher=Eurostat |website=ec.europa.eu/eurostat |access-date=19 June 2020 |archive-date=18 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201218154953/https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tec00120&plugin=1 |url-status=live }}</ref> National PPP GDP was estimated at $143.1 billion in 2016, with a per capita value of $20,116.<ref name="imf2">{{cite web |url=http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=53&pr.y=5&sy=2011&ey=2016&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=918&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CLP&grp=0&a= |title=Bulgaria |publisher=International Monetary Fund |access-date=12 March 2017 |archive-date=23 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210423114058/https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=53&pr.y=5&sy=2011&ey=2016&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=918&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CLP&grp=0&a= |url-status=live }}</ref> Economic growth statistics take into account illegal transactions from the [[informal economy]], which is the largest in the EU as a percentage of economic output.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.occrp.org/en/27-ccwatch/cc-watch-briefs/2616-eu-countries-to-begin-counting-drugs-prostitution-in-economic-growth |title=EU: Countries to Begin Counting Drugs, Prostitution in Economic Growth |publisher=Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project |date=9 September 2014 |access-date=16 July 2018 |archive-date=17 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191117102436/https://www.occrp.org/en/27-ccwatch/cc-watch-briefs/2616-eu-countries-to-begin-counting-drugs-prostitution-in-economic-growth |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/pdf/themes/06_shadow_economy.pdf |title=Shadow Economy |publisher=Eurostat |date=2012 |access-date=20 December 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121114234654/http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/pdf/themes/06_shadow_economy.pdf |archive-date=14 November 2012}}</ref> The [[Bulgarian National Bank]] issues the national currency, [[Bulgarian lev|lev]], which is pegged to the euro at a rate of 1.95583 levа per euro.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bnb.bg/Statistics/StExternalSector/StExchangeRates/StERFixed/index.htm |script-title=bg:Курсове на българския лев към еврото и към валутите на държавите, приели еврото |trans-title=Exchange rates of the lev to the euro and Eurozone currencies replaced by the euro |publisher=Bulgarian National Bank |access-date=16 October 2018 |language=bg |archive-date=5 June 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190605060830/http://www.bnb.bg/Statistics/StExternalSector/StExchangeRates/StERFixed/index.htm |url-status=live }}</ref>

| |

| | |

| After several consecutive years of high growth, repercussions of the [[financial crisis of 2007–2008]] resulted in a 3.6% contraction of GDP in 2009 and increased unemployment.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=BG |title=Bulgaria: GDP growth (annual %) |publisher=The World Bank |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=12 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512223312/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=BG |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?end=2017&locations=BG&start=1991&view=chart |title=Bulgaria: Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate) |year=2018 |publisher=The World Bank |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=10 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220510101411/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?end=2017&locations=BG&start=1991&view=chart |url-status=live }}</ref> Positive growth was restored in 2010 but intercompany debt exceeded $59 billion, meaning that 60% of all Bulgarian companies were mutually indebted.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://bnr.bg/sites/en/Economy/Pages/1706compandebts.aspx |title=Inter-company debt – one of Bulgarian economy's serious problems |publisher=Bulgarian National Radio |first=Tanya |last=Harizanova |date=17 June 2010 |access-date=10 July 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121101112308/http://bnr.bg/sites/en/Economy/Pages/1706compandebts.aspx |archive-date=1 November 2012}}</ref> By 2012, it had increased to $97 billion, or 227% of GDP.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://dnes.dir.bg/ikonomika/firmi-bozhidar-danev-balgarskata-stopanska-kamara-zadalzhenia-12811577 |script-title=bg:Бизнесът очерта уникална диспропорция в България |trans-title=Business points to a major disproportion in Bulgaria |publisher=Dir.bg |language=bg |date=14 January 2013 |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=12 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512223329/https://dnes.dir.bg/ikonomika/firmi-bozhidar-danev-balgarskata-stopanska-kamara-zadalzhenia-12811577 |url-status=live }}</ref> The government implemented strict austerity measures with IMF and EU encouragement to some positive fiscal results, but the social consequences of these measures, such as increased [[economic inequality|income inequality]] and accelerated outward migration, have been "catastrophic" according to the [[International Trade Union Confederation]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.novinite.com/view_news.php?id=144010 |title=ITUC Frontlines Report 2012: Section on Bulgaria |publisher=[[Novinite]] |date=10 October 2012 |access-date=10 October 2012 |archive-date=20 October 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121020042322/http://www.novinite.com/view_news.php?id=144010 |url-status=live }}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Siphoning of public funds to the families and relatives of politicians from incumbent parties has resulted in fiscal and welfare losses to society.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.novinite.com/articles/118351/Bulgaria%2C+Romania+Rapped+for+Public+Procurement+Fraud |title=Bulgaria, Romania Rapped for Public Procurement Fraud |publisher=[[Novinite]] |date=21 July 2010 |access-date=16 July 2018 |archive-date=16 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180716194814/https://www.novinite.com/articles/118351/Bulgaria%2C+Romania+Rapped+for+Public+Procurement+Fraud |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Center for the Study of Democracy |title=Anti-corruption Reforms in Bulgaria: Key Results and Risks |publisher=Center for the Study of Democracy |page=44 |year=2007 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EgHHCbYKZXoC&pg=PA44 |isbn=9789544771461 |access-date=3 March 2024 |archive-date=15 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230115223045/https://books.google.com/books?id=EgHHCbYKZXoC&pg=PA44 |url-status=live }}</ref> Bulgaria ranks 71st in the [[Corruption Perceptions Index]]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017 |title=Corruption Perceptions Index: Transparency International |year=2017 |publisher=[[Transparency International]] |access-date=16 July 2018 |archive-date=21 February 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180221190927/https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017 |url-status=dead}}</ref> and experiences the worst levels of [[corruption]] in the European Union, a phenomenon that remains a source of profound public discontent.<ref name="cloud">{{cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/28/bulgaria-corruption-eu-presidency-far-right-minority-parties-concerns |title=Cloud of corruption hangs over Bulgaria as it takes up EU presidency |newspaper=The Guardian |first=Jennifer |last=Rankin |date=28 December 2017 |access-date=9 July 2018 |archive-date=25 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220525205308/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/28/bulgaria-corruption-eu-presidency-far-right-minority-parties-concerns |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/bulgaria/11290458/Bulgarian-corruption-at-15-year-high.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220110/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/bulgaria/11290458/Bulgarian-corruption-at-15-year-high.html |archive-date=10 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |title=Bulgarian corruption at 15-year high |newspaper=The Telegraph |date=12 December 2014 |access-date=9 July 2018}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Along with organised crime, corruption has resulted in a rejection of the country's [[Schengen Area]] application and withdrawal of foreign investment.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bulgaria-security/bulgarian-border-officers-suspended-over-airport-security-lapse-idUSKBN1H00L2 |title=Bulgarian border officers suspended over airport security lapse |work=Reuters |date=24 March 2018 |access-date=9 July 2018 |archive-date=16 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220416234027/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bulgaria-security/bulgarian-border-officers-suspended-over-airport-security-lapse-idUSKBN1H00L2 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-bulgaria/bulgaria-savors-eu-embrace-despite-critics-idUSKBN1F02V8 |title=Bulgaria savors EU embrace despite critics |work=Reuters |first=Alastair |last=Macdonald |date=11 January 2018 |access-date=9 July 2018 |archive-date=30 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220430052505/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-bulgaria/bulgaria-savors-eu-embrace-despite-critics-idUSKBN1F02V8 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="reuters_USKBN1F61EQ">{{cite news |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bulgaria-government/bulgarias-government-faces-no-confidence-vote-over-corruption-idUSKBN1F61EQ |title=Bulgaria's government faces no-confidence vote over corruption |work=Reuters |first=Angel |last=Krasimirov |date=17 January 2018 |access-date=9 July 2018 |archive-date=12 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512223406/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bulgaria-government/bulgarias-government-faces-no-confidence-vote-over-corruption-idUSKBN1F61EQ |url-status=live }}</ref> Government officials reportedly engage in embezzlement, influence trading, government procurement violations and bribery with impunity.<ref name="SG1">{{cite web |url=https://sofiaglobe.com/2018/04/21/us-state-dept-criticises-bulgaria-on-prisons-judiciary-corruption-people-trafficking-and-violence-against-minorities/ |title=US State Dept criticises Bulgaria on prisons, judiciary, corruption, people-trafficking and violence against minorities |publisher=The Sofia Globe |date=21 April 2018 |access-date=9 July 2018 |archive-date=6 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201106135613/https://sofiaglobe.com/2018/04/21/us-state-dept-criticises-bulgaria-on-prisons-judiciary-corruption-people-trafficking-and-violence-against-minorities/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Government procurement in particular is a critical area in corruption risk. An estimated 10 billion leva ($5.99 billion) of state budget and [[Structural Funds and Cohesion Fund|European cohesion]] funds are spent on public tenders each year;<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.24chasa.bg/novini/article/5316312 |script-title=bg:10 млрд. лв. годишно се харчат с обществени поръчки |trans-title=10 bln. leva are spent on public procurement every year |newspaper=24 Chasa |date=21 February 2016 |access-date=30 July 2018 |language=bg |archive-date=12 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512223417/https://www.24chasa.bg/novini/article/5316312 |url-status=live }}</ref> nearly 14 billion ($8.38 billion) were spent on public contracts in 2017 alone.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.capital.bg/politika_i_ikonomika/bulgaria/2017/12/29/3104548_rekord_pri_obshtestvenite_poruchki_otkriti_sa_turgove/ |script-title=bg:Рекорд при обществените поръчки: открити са търгове за почти 14 млрд. лв. |trans-title=A record in public procurement: tenders worth nearly 14 billion lv unveiled |publisher=Kapital Daily |first=Ivaylo |last=Stanchev |date=29 December 2017 |access-date=16 July 2018 |language=bg |archive-date=10 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220510101518/https://www.capital.bg/politika_i_ikonomika/bulgaria/2017/12/29/3104548_rekord_pri_obshtestvenite_poruchki_otkriti_sa_turgove/ |url-status=live }}</ref> A large share of these contracts are awarded to a few politically connected<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Stefanov |first1=Ruslan |title=The Bulgarian Public Procurement Market: Corruption Risks and Dynamics in the Construction Sector |journal=Government Favouritism in Europe: The Anticorruption Report 3 |date=2015 |issue=3/2015 |page=35 |url=http://www.romaniacurata.ro/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/ACRVolume3_Ch3_Bulgaria.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.romaniacurata.ro/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/ACRVolume3_Ch3_Bulgaria.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |access-date=6 August 2018 |doi=10.2307/j.ctvdf0g12.6}}</ref> companies amid widespread irregularities, procedure violations and tailor-made award criteria.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/how/improving-investment/public-procurement/study/country_profile/bg.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/how/improving-investment/public-procurement/study/country_profile/bg.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |title=Public procurement in Bulgaria |publisher=European Commission |date=2015 |access-date=16 July 2018}}</ref> Despite repeated criticism from the [[European Commission]],<ref name="reuters_USKBN1F61EQ" /> EU institutions refrain from taking measures against Bulgaria because it supports Brussels on a number of issues, unlike [[Poland]] or [[Hungary]].<ref name="cloud" />

| |

| | |

| === Structure and sectors ===

| |

| The labour force is 3.36 million people,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/218.html#BU |title=Field listing: Labor force |website=[[The World Factbook]] |publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]] |access-date=15 December 2019 |archive-date=7 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200307175501/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/218.html#BU |url-status=dead}}</ref> of whom 6.8% are employed in agriculture, 26.6% in industry and 66.6% in the services sector.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/219.html#BU |title=Field listing: Labor force by occupation |website=[[The World Factbook]] |publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]] |access-date=15 December 2019 |archive-date=20 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190420181021/https://www.cia.gov/Library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/219.html#BU |url-status=dead}}</ref> Extraction of metals and minerals, production of [[chemical industry|chemicals]], [[machinery industry|machine building]], steel, biotechnology, tobacco, food processing and [[refined petroleum fuel|petroleum refining]] are among the major industrial activities.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Bulgaria/Economy#ref42702 |title=Bulgaria – Manufacturing |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |first=John D. |last=Bell |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=10 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220510100730/https://www.britannica.com/place/Bulgaria/Economy#ref42702 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/216.html#BU |title=Field listing: Industries |website=[[The World Factbook]] |publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]] |access-date=15 December 2019 |archive-date=18 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201218182242/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/216.html#BU |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/bulgaria-selling-steel |title=Bulgaria: Selling off steel |date=31 August 2011 |publisher=Oxford Business Group |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=19 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220419162309/https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/bulgaria-selling-steel |url-status=live }}</ref> Mining alone employs 24,000 people and generates about 5% of the country's GDP; the number of employed in all mining-related industries is 120,000.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.novinite.com/articles/170584/Mining+Industry+Accounts+for+5+of+Bulgaria%27s+GDP+%E2%80%93+Energy+Minister |title=Mining Industry Accounts for 5% of Bulgaria's GDP – Energy Minister |publisher=[[Novinite]] |date=29 August 2015 |access-date=20 July 2018 |archive-date=19 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220419163046/https://www.novinite.com/articles/170584/Mining+Industry+Accounts+for+5+of+Bulgaria%27s+GDP+%E2%80%93+Energy+Minister |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Ore exports">{{cite news |title=Bulgaria's ore exports rise 10% in H1 2011 – industry group |url=http://thesofiaecho.com/2011/08/18/1141389_bulgarias-ore-exports-rise-10per-cent-in-h1-2011-industry-group |date=18 August 2011 |newspaper=The Sofia Echo |access-date=20 December 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120316132149/http://thesofiaecho.com/2011/08/18/1141389_bulgarias-ore-exports-rise-10per-cent-in-h1-2011-industry-group |archive-date=16 March 2012}}</ref> Bulgaria is Europe's fifth-largest coal producer.<ref name="Ore exports" /><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/data/browser/#/?pa=0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000g&c=1438j008006gg6168g80a4k000e8ag00gg0004gc00ho00go&ct=0&tl_id=1-A&vs=INTL.7-1-ALB-TST.A&ord=CR&cy=2015&vo=0&v=H&start=2014&end=2016 |title=Total Primary Coal Production (Thousand Short Tons) |publisher=U.S. Energy Information Administration |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=27 April 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170427031435/https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/data/browser/#/?pa=0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000g&c=1438j008006gg6168g80a4k000e8ag00gg0004gc00ho00go&ct=0&tl_id=1-A&vs=INTL.7-1-ALB-TST.A&ord=CR&cy=2015&vo=0&v=H&start=2014&end=2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> Local deposits of coal, iron, copper and lead are vital for the manufacturing and energy sectors.{{Sfn|Resource Base}} The main destinations of Bulgarian exports outside the EU are Turkey, China and Serbia, while Russia, Turkey and China are by far the largest import partners. Most of the exports are manufactured goods, machinery, chemicals, fuel products and food.<ref>{{cite web |title=Trade In Goods of Bulgaria With Third Countries In the Period January – October 2019 (Preliminary Data) |publisher=National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria |pages=7, 8 |url=https://www.nsi.bg/sites/default/files/files/pressreleases/FTS_Extrastat_2019-10_en_HDT5DBO.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://www.nsi.bg/sites/default/files/files/pressreleases/FTS_Extrastat_2019-10_en_HDT5DBO.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |date=November 2019 |access-date=15 December 2019}}</ref> Two-thirds of food and agricultural exports go to [[OECD]] countries.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.oecd.org/agriculture/agricultural-policies/40354124.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.oecd.org/agriculture/agricultural-policies/40354124.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |title=Agricultural Policies in non-OECD countries: Monitoring and Evaluation |publisher=[[OECD]] |date=2007 |access-date=28 July 2018}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Although cereal and vegetable output dropped by 40% between 1990 and 2008,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fao.org/regional/seur/Review/Bulgaria.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080328063300/http://www.fao.org/regional/seur/Review/Bulgaria.htm |title=Bulgaria – Natural conditions, farming traditions and agricultural structures |publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization |archive-date=28 March 2008 |access-date=2 November 2011}}</ref> output in grains has since increased, and the 2016–2017 season registered the biggest grain output in a decade.<ref name="UNdata">{{cite web |url=http://data.un.org/en/iso/bg.html |title=Bulgaria – Economic Summary, UNData, United Nations |publisher=United Nations |access-date=20 December 2011 |archive-date=22 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211222045515/http://data.un.org/en/iso/bg.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bta.bg/en/c/DF/id/1628901 |title=Experts: Bumper Year for Wheat Producers in Dobrich Region |publisher=Bulgarian Telegraph Agency |date=4 August 2017 |access-date=20 July 2018 |archive-date=21 January 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220121031617/http://www.bta.bg/en/c/DF/id/1628901 |url-status=live }}</ref> [[Maize]], [[barley]], [[oats]] and [[rice]] are also grown. Quality [[Turkish tobacco|Oriental tobacco]] is a significant industrial crop.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Bulgaria/Economy#ref42701 |title=Bulgaria – Agriculture |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |first=John D. |last=Bell |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=10 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220510100730/https://www.britannica.com/place/Bulgaria/Economy#ref42701 |url-status=live }}</ref> Bulgaria is also the largest producer globally of [[lavender oil|lavender]] and [[rose oil]], both widely used in fragrances.<ref name="CENTCOM" /><ref>{{cite web |url=http://bnr.bg/en/post/100837137/bulgarian-rose-oil-keeps-its-top-place-on-world-market |title=Bulgarian rose oil keeps its top place on world market |publisher=Bulgarian National Radio |first=Miglena |last=Ivanova |date=31 May 2017 |access-date=20 July 2018 |archive-date=16 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220416234209/https://bnr.bg/en/post/100837137/bulgarian-rose-oil-keeps-its-top-place-on-world-market |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.novinite.com/articles/185754/Bulgaria+is+Again+the+World%27s+First+Producer+of+Lavender+Oil |title=Bulgaria is Again the World's First Producer of Lavender Oil |publisher=[[Novinite]] |date=30 November 2017 |access-date=20 July 2018 |archive-date=30 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220430052505/https://www.novinite.com/articles/185754/Bulgaria+is+Again+the+World%27s+First+Producer+of+Lavender+Oil |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.foxnews.com/world/2014/07/16/bulgaria-tops-lavender-oil-production-outpacing-france.html |title=Bulgaria tops lavender oil production, outpacing France |publisher=Fox News |date=16 July 2014 |access-date=12 September 2018 |archive-date=12 September 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180912165804/http://www.foxnews.com/world/2014/07/16/bulgaria-tops-lavender-oil-production-outpacing-france.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Within the services sector, [[Tourism in Bulgaria|tourism]] is a significant contributor to economic growth. [[Sofia]], [[Plovdiv]], [[Veliko Tarnovo]], coastal resorts [[Albena]], [[Golden Sands]] and [[Sunny Beach]] and winter resorts [[Bansko]], [[Pamporovo]] and [[Borovets]] are some of the locations most visited by tourists.<ref>{{cite news |title=Europe (without the euro) |url=https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2009/apr/20/europe-budget-travel-short-haul-cheap |newspaper=The Guardian |date=20 April 2009 |access-date=20 December 2011 |archive-date=31 October 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131031004121/http://www.theguardian.com/travel/2009/apr/20/europe-budget-travel-short-haul-cheap |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Bulgaria/Economy#ref253978 |title=Bulgaria – Tourism |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |first=John D. |last=Bell |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=10 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220510100730/https://www.britannica.com/place/Bulgaria/Economy#ref253978 |url-status=live }}</ref> Most visitors are Romanian, Turkish, Greek and German.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nsi.bg/bg/content/1969/%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%B5%D1%89%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%8F-%D0%BD%D0%B0-%D1%87%D1%83%D0%B6%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%86%D0%B8-%D0%B2-%D0%B1%D1%8A%D0%BB%D0%B3%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%8F-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%BC%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%B5%D1%86%D0%B8-%D0%B8-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D1%81%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8 |script-title=bg:Посещения на чужденци в България по месеци и по страни |trans-title=Arrivals of foreigners in 2017 by month and country of origin |publisher=National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria |date=15 February 2019 |access-date=15 December 2019 |language=bg |archive-date=5 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200605070014/https://www.nsi.bg/bg/content/1969/%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%B5%D1%89%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%8F-%D0%BD%D0%B0-%D1%87%D1%83%D0%B6%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%86%D0%B8-%D0%B2-%D0%B1%D1%8A%D0%BB%D0%B3%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%8F-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%BC%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%B5%D1%86%D0%B8-%D0%B8-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D1%81%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8 |url-status=live }}</ref> Tourism is additionally encouraged through the [[100 Tourist Sites of Bulgaria|100 Tourist Sites]] system.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.bnr.bg/en/post/100103688/100-tourist-sites-of-bulgaria |title=100 Tourist Sites of Bulgaria |publisher=Bulgarian National Radio |first=Alexander |last=Markov |date=3 October 2011 |access-date=15 December 2019 |archive-date=15 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191215212348/https://www.bnr.bg/en/post/100103688/100-tourist-sites-of-bulgaria |url-status=live }}</ref>

| |

| | |

| === Science and technology ===

| |

| {{Main|Science and technology in Bulgaria}}

| |

| [[File:BulgariaSat-1 Mission (35491530485).jpg|thumb|right|upright|alt=A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket launching BulgariaSat-1 in June 2017|The launch of BulgariaSat-1 by SpaceX]]

| |

| | |

| Spending on [[research and development]] amounts to 0.78% of GDP,{{Sfn|NSI Brochure|2018|page=19}} and the bulk of public R&D funding goes to the [[Bulgarian Academy of Sciences]] (BAS).<ref name="EUpresidency">{{cite web |url=https://www.novinite.com/articles/188930/EU+Presidency+Puts+Lagging+Bulgarian+Science+in+the+Spotlight |title=EU Presidency Puts Lagging Bulgarian Science in the Spotlight |publisher=[[Novinite]] |date=22 March 2018 |access-date=14 July 2018 |archive-date=15 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180715011433/https://www.novinite.com/articles/188930/EU+Presidency+Puts+Lagging+Bulgarian+Science+in+the+Spotlight |url-status=live }}</ref> Private businesses accounted for more than 73% of R&D expenditures and employed 42% of Bulgaria's 22,000 researchers in 2015.<ref name="R&D spending">{{cite web |url=https://www.novinite.com/articles/177126/R%26D+Spending+in+Bulgaria+Up+in+2015%2C+Mostly+Driven+by+Businesses |title=R&D Spending in Bulgaria Up in 2015, Mostly Driven by Businesses |publisher=[[Novinite]] |date=31 October 2016 |access-date=14 July 2018 |archive-date=2 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200202160330/https://www.novinite.com/articles/177126/R%26D+Spending+in+Bulgaria+Up+in+2015%2C+Mostly+Driven+by+Businesses |url-status=live }}</ref> The same year, Bulgaria ranked 39th out of 50 countries in the [[Bloomberg Innovation Index]], the highest score being in education (24th) and the lowest in value-added manufacturing (48th).<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2015-innovative-countries/ |title=The 2015 Bloomberg Innovation Index |newspaper=Bloomberg.com |publisher=Bloomberg |access-date=14 July 2018 |archive-date=25 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191225075316/https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2015-innovative-countries/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Bulgaria was ranked 38th in the [[Global Innovation Index]] in 2023.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=WIPO |title=Global Innovation Index 2023, 15th Edition |url=https://www.wipo.int/global_innovation_index/en/2023/index.html |access-date=28 October 2023 |website=www.wipo.int |doi=10.34667/tind.46596 |language=en |archive-date=22 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231022042128/https://www.wipo.int/global_innovation_index/en/2023/index.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Chronic government underinvestment in research since 1990 has forced many professionals in science and engineering to leave Bulgaria.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Shopov |first1=V. |title=The impact of the European scientific area on the 'Brain leaking' problem in the Balkan countries |journal=Nauka |date=2007 |issue=1/2007}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Despite the lack of funding, research in chemistry, [[materials science]] and [[physics]] remains strong.<ref name="EUpresidency" /> Antarctic research is actively carried out through the [[St. Kliment Ohridski Base]] on [[Livingston Island]] in [[Western Antarctica]].<ref>[https://data.aad.gov.au/aadc/gaz/scar/display_name.cfm?gaz_id=105044 St. Kliment Ohridski Base.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140319060854/https://data.aad.gov.au/aadc/gaz/scar/display_name.cfm?gaz_id=105044 |date=19 March 2014 }} SCAR [[Composite Antarctic Gazetteer]]</ref><ref>Ivanov, Lyubomir (2015). [http://livingston-island.weebly.com/ General Geography and History of Livingston Island.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150708084208/http://livingston-island.weebly.com/ |date=8 July 2015 }} In: ''Bulgarian Antarctic Research: A Synthesis''. Eds. C. Pimpirev and N. Chipev. Sofia: St. Kliment Ohridski University Press. pp. 17–28. {{ISBN|978-954-07-3939-7}}</ref> The [[information and communication technologies]] (ICT) sector generates three per cent of economic output and employs 40,000<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.ft.com/content/f9a35122-44f4-11e6-9b66-0712b3873ae1 |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221210/https://www.ft.com/content/f9a35122-44f4-11e6-9b66-0712b3873ae1 |archive-date=10 December 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |title=Bulgaria strives to become tech capital of the Balkans |newspaper=The Financial Times |first=Kerin |last=Hope |date=17 October 2016 |access-date=15 July 2018}}</ref> to 51,000 software engineers.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bta.bg/en/c/DF/id/1762498 |title=Bulgaria's ICT Sector Turnover Trebled over Last Seven Years – Deputy Economy Minister |publisher=Bulgarian Telegraph Agency |date=12 March 2018 |access-date=15 July 2018 |archive-date=17 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191117174213/http://www.bta.bg/en/c/DF/id/1762498 |url-status=live }}</ref> Bulgaria was known as a "Communist [[Silicon Valley]]" during the Soviet era due to its key role in [[COMECON]] computing technology production.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.delta.tudelft.nl/article/great-bulgarian-braindrain |title=The Great Bulgarian BrainDrain |publisher=Delft Technical University |first=David |last=McMullin |date=2 October 2003 |access-date=15 July 2018 |archive-date=17 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191117174215/https://www.delta.tudelft.nl/article/great-bulgarian-braindrain |url-status=live }}</ref> A concerted effort by the communist government to teach computing and IT skills in schools also indirectly made Bulgaria a major source of [[computer virus]]es in the 1980s and 90s.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Petrov |first=Victor |date=30 September 2021 |title=Socialist Cyborgs |url=https://logicmag.io/kids/socialist-cyborgs/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210917195506/https://logicmag.io/kids/socialist-cyborgs/ |archive-date=17 September 2021}}</ref> The country is a regional leader in [[supercomputer|high performance computing]]: it operates ''Avitohol'', the most powerful supercomputer in Southeast Europe, and will host one of the eight [[petascale computing|petascale]] [[European High-Performance Computing Joint Undertaking|EuroHPC]] supercomputers.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.capital.bg/biznes/tehnologii_i_nauka/2018/06/22/3203630_shum_tok_i_superkompjutri/ |script-title=bg:Малката изчислителна армия на България |trans-title=Bulgaria's small computing army |publisher=Kapital Daily |first=Yoan |last=Zapryanov |date=22 June 2018 |access-date=15 July 2018 |language=bg |archive-date=17 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191117174209/https://www.capital.bg/biznes/tehnologii_i_nauka/2018/06/22/3203630_shum_tok_i_superkompjutri/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-19-2868_en.htm |title=Digital Single Market: Europe announces eight sites to host world-class supercomputers |publisher=European Commission |date=7 June 2019 |access-date=15 August 2019 |archive-date=11 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190811230320/https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-19-2868_en.htm |url-status=live }}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Bulgaria has made numerous contributions to [[space exploration]].<ref name="Interkosmos">{{cite book |last1=Burgess |first1=Colin |last2=Vis |first2=Bert |title=Interkosmos: The Eastern Bloc's Early Space Program |publisher=Springer |pages=247–250 |year=2016 |isbn=978-3-319-24161-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MG__CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA247 |access-date=3 March 2024 |archive-date=15 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230115223024/https://books.google.com/books?id=MG__CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA247 |url-status=live }}</ref> These include two scientific satellites, more than 200 payloads and 300 experiments in Earth orbit, as well as [[Bulgarian cosmonaut program|two cosmonauts]] since 1971.<ref name="Interkosmos" /> Bulgaria was the first country to grow [[wheat]] and vegetables [[Plants in space|in space]] with its [[SVET plant growth system|Svet]] [[greenhouse]]s on the [[Mir space station]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.novinite.com/articles/127387/Cosmonauts+Eager%2C+Hopeful+for+Reboot+of+Bulgaria%27s+Space+Program |title=Cosmonauts Eager, Hopeful for Reboot of Bulgaria's Space Program |publisher=[[Novinite]] |date=17 April 2011 |access-date=15 July 2018 |archive-date=15 August 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180815055331/https://www.novinite.com/articles/127387/Cosmonauts+Eager%2C+Hopeful+for+Reboot+of+Bulgaria%27s+Space+Program |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ivanova |first1=Tanya |title=Six-month space greenhouse experiments—a step to creation of future biological life support systems |journal=Acta Astronautica |date=1998 |volume=42 |issue=1–8 |pages=11–23 |doi=10.1016/S0094-5765(98)00102-7 |pmid=11541596 |bibcode=1998AcAau..42...11I}}</ref> It was involved in the development of the [[Granat]] [[Gamma-ray astronomy|gamma-ray observatory]]<ref name="RESS" /> and the [[Vega program]], particularly in modelling trajectories and guidance [[algorithms]] for both Vega probes.<ref>{{cite book |last=Dimitrova |first=Milena |title=Златните десятилетия на българската електроника |trans-title=The Golden Decades of Bulgarian Electronics |publisher=Trud |pages=257–258 |year=2008 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jqJ6Ocql0XIC&pg=PA257 |isbn=9789545288456 |access-date=3 March 2024 |archive-date=15 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230115223025/https://books.google.com/books?id=jqJ6Ocql0XIC&pg=PA257 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Badescu |first1=Viorel |last2=Zacny |first2=Kris |title=Inner Solar System: Prospective Energy and Material Resources |publisher=Springer |page=276 |year=2015 |isbn=978-3-319-19568-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZrAYCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA276 |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=15 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230115223025/https://books.google.com/books?id=ZrAYCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA276 |url-status=live }}</ref> Bulgarian instruments have been used in the [[exploration of Mars]], including a spectrometer that took the first high quality [[spectroscopy|spectroscopic]] images of Martian moon [[Phobos (moon)|Phobos]] with the [[Phobos 2]] probe.<ref name="Interkosmos" /><ref name="RESS">{{cite book |last1=Harland |first1=David M. |last2=Ulivi |first2=Paolo |title=Robotic Exploration of the Solar System: Part 2: Hiatus and Renewal, 1983–1996 |publisher=Springer |page=155 |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-387-78904-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dZyaAAVwg5QC&pg=PA155 |access-date=3 March 2024 |archive-date=15 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230115223025/https://books.google.com/books?id=dZyaAAVwg5QC&pg=PA155 |url-status=live }}</ref> [[Cosmic ray|Cosmic radiation]] en route to and around the planet has been mapped by [[Liulin type instruments|Liulin-ML]] dosimeters on the [[ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter|ExoMars TGO]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Semkova |first1=Jordanka |last2=Dachev |first2=Tsvetan |title=Radiation environment investigations during ExoMars missions to Mars – objectives, experiments and instrumentation |journal=Comptes Rendus de l'Académie Bulgare des Sciences |date=2015 |volume=47 |issue=25 |pages=485–496 |url=https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:47073133 |access-date=6 August 2018 |issn=1310-1331 |archive-date=8 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308141639/https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:47073133 |url-status=live }}</ref> [[RADOM-7|Variants]] of these instruments have also been fitted on the [[International Space Station]] and the [[Chandrayaan-1]] lunar probe.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.isro.org/chandrayaan/htmls/radom_bas.htm |title=Radiation Dose Monitor Experiment (RADOM) |publisher=ISRO |access-date=20 December 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120119044239/http://www.isro.org/chandrayaan/htmls/radom_bas.htm |archive-date=19 January 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Dachev |first1=Ts. |last2=Dimitrov |first2=Pl. |last3=Tomov |first3=B. |last4=Matviichuk |first4=Yu. |last5=Spurny |first5=F. |last6=Ploc |first6=O. |title=Liulin-type spectrometry-dosimetry instruments |journal=Radiation Protection Dosimetry |date=2011 |volume=144 |issue=1–4 |pages=675–679 |doi=10.1093/rpd/ncq506 |pmid=21177270 |issn=1742-3406}}</ref> Another lunar mission, [[SpaceIL]]'s ''Beresheet'', was also equipped with a Bulgarian-manufactured imaging payload.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://dariknews.bg/novini/liubopitno/bylgarska-kamera-leti-kym-lunata-2155077 |title=Bulgarian Camera Flies to the Moon |publisher=Darik News |date=22 March 2019 |access-date=30 March 2019 |archive-date=30 March 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190330171924/https://dariknews.bg/novini/liubopitno/bylgarska-kamera-leti-kym-lunata-2155077 |url-status=live }}</ref> Bulgaria's first [[Geosynchronous satellite|geostationary communications satellite]]—[[BulgariaSat-1]]—was launched by [[SpaceX]] in 2017.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.spacex.com/news/2017/06/23/bulgariasat-1-mission |title=BulgariaSat-1 Mission |publisher=SpaceX |access-date=15 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191117174220/https://www.spacex.com/news/2017/06/23/bulgariasat-1-mission |archive-date=17 November 2019 |url-status=dead}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| === Infrastructure ===

| |

| {{Main|Energy in Bulgaria|Transport in Bulgaria}}

| |

| [[File:Trakia highway near to Nova Zagora.jpg|thumb|left|alt=Trakiya motorway, one of the main national motorways|[[Trakia motorway]]]]

| |

| | |

| Telephone services are widely available, and a central digital trunk line connects most regions.{{Sfn|Library of Congress|2006|page=14}} [[Vivacom]] (BTC) serves more than 90% of fixed lines and is one of the three operators providing mobile services, along with [[Mtel (Bulgaria)|A1]] and [[Telenor (Bulgaria)|Telenor]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/sites/digital-agenda/files/BG_Country_Chapter_17th_Report_0.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/sites/digital-agenda/files/BG_Country_Chapter_17th_Report_0.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |title=Bulgaria: 2011 Telecommunication Market and Regulatory Developments |publisher=European Commission |page=2 |date=2011 |access-date=19 March 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://novinite.com/view_news.php?id=132606 |title=Bulgaria Opens Tender for Fourth Mobile Operator |publisher=[[Novinite]] |date=3 October 2011 |access-date=20 December 2011 |archive-date=17 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191117114747/https://www.novinite.com/view_news.php?id=132606 |url-status=live }}</ref> [[Internet]] penetration stood at 69.2% of the population aged 16–74 and 78.9% of households in 2020.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nsi.bg/en/content/6105/individuals-regularly-using-internet |title=Individuals regularly using the Internet (Every day or at least once a week) |publisher=National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria |date=27 February 2021 |access-date=27 February 2021 |archive-date=24 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210224170445/https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/6105/individuals-regularly-using-internet |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/6099/households-internet-access-home |title=Households with Internet access at home |publisher=National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria |date=27 February 2021 |access-date=27 February 2021 |archive-date=11 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200811160642/https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/6099/households-internet-access-home |url-status=dead}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Bulgaria's strategic geographic location and well-developed energy sector make it a key European energy centre despite its lack of significant fossil fuel deposits.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/energy-hub |title=Energy Hub |publisher=Oxford Business Group |date=13 October 2008 |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=28 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180728131509/https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/energy-hub |url-status=live }}</ref> Thermal power plants generate 48.9% of electricity, followed by [[nuclear power]] from the [[Kozloduy Nuclear Power Plant|Kozloduy reactors]] (34.8%) and [[renewable energy|renewable sources]] (16.3%).{{Sfn|NSI Brochure|2018|page=47}} Equipment for a second nuclear power station at [[Belene Nuclear Power Plant|Belene]] has been acquired, but the fate of the project remains uncertain.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bulgaria-energy-nuclear/bulgaria-must-work-to-restart-belene-nuclear-project-parliament-idUSKCN1J31DP |title=Bulgaria must work to restart Belene nuclear project: parliament |work=Reuters |first=Angel |last=Krasimirov |date=7 June 2018 |access-date=24 October 2018 |archive-date=24 October 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181024035507/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bulgaria-energy-nuclear/bulgaria-must-work-to-restart-belene-nuclear-project-parliament-idUSKCN1J31DP |url-status=live }}</ref> Installed capacity amounts to 12,668 MW, allowing Bulgaria to exceed domestic demand and export energy.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.export.gov/article?id=Bulgaria-Power-Generation-Oil-and-Gas-Renewable-Sources-of-Energy-and-Energy-Efficiency |title=Bulgaria – Power Generation |publisher=[[International Trade Administration]] |access-date=15 June 2018 |archive-date=15 June 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180615190654/https://www.export.gov/article?id=Bulgaria-Power-Generation-Oil-and-Gas-Renewable-Sources-of-Energy-and-Energy-Efficiency |url-status=live }}</ref>

| |

| | |

| The national road network has a total length of {{convert|19512|km}},<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2085rank.html#bu |title=Country comparison: Total road length |website=[[The World Factbook]] |publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]] |access-date=15 June 2018 |archive-date=7 September 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170907162530/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2085rank.html#bu |url-status=dead}}</ref> of which {{convert|19235|km}} are paved. Railroads are a major mode of freight transportation, although highways carry a progressively larger share of freight. Bulgaria has {{convert|6238|km}} of railway track, {{Sfn|Library of Congress|2006|page=14}} with rail links available to Romania, Turkey, Greece, and Serbia, and express trains serving direct routes to [[Kyiv]], [[Minsk]], [[Moscow]] and [[Saint Petersburg]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.eurail.com/en/get-inspired/top-destinations/bulgaria-train |title=Trains in Bulgaria |publisher=EuRail |access-date=28 July 2018 |archive-date=12 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512223607/https://www.eurail.com/en/get-inspired/top-destinations/bulgaria-train |url-status=dead}}</ref> Sofia is the country's air travel hub, while Varna and Burgas are the principal maritime trade ports.{{Sfn|Library of Congress|2006|page=14}}

| |

| | |

| == Demographics ==

| |

| {{Main|Demographics of Bulgaria}}

| |

| {{Pie chart

| |

| | caption = Ethnic groups in Bulgaria (2021 census)<ref name="Infostat">{{cite web |title=Population by Ethnic Group, Statistical Regions, Districts and Municipalities as of 07/09/2021 |author=National Statistical Institute |year=2022 |lang=en |url=https://infostat.nsi.bg/infostat/pages/reports/result.jsf?x_2=2025 |access-date=6 September 2023 |archive-date=12 February 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230212081708/https://infostat.nsi.bg/infostat/pages/reports/result.jsf?x_2=2025 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="NSI2021">{{cite web |title=Ethno-Cultural Characteristics of the Bulgarian Population as at 7 September 2021 |author=National Statistical Institute |date=24 November 2022 |lang=bg |url=https://nsi.bg/sites/default/files/files/pressreleases/Census2021_ethnos.pdf |access-date=25 November 2022 |archive-date=24 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221124195716/https://nsi.bg/sites/default/files/files/pressreleases/Census2021_ethnos.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref>

| |

| |radius =80

| |

| | thumb = left

| |

| | label1 =[[Bulgarians]]|color1 = Salmon

| |

| | value1 =84.57

| |

| | label2 =[[Bulgarian Turks]]| color2 = DodgerBlue

| |

| | value2 =8.40

| |

| | label3 = [[Romani people in Bulgaria|Romani]] |color3 = Yellow

| |

| | value3 =4.41

| |

| | label4 = Other| color4 = DarkOrchid

| |

| | value4 = 1.31

| |

| | label5 = Undeclared | color5 = Maroon

| |

| | value5 =1.31

| |

| }}

| |