Sengshui: Difference between revisions

m (Removed redirect to Kingdom of Kasavy) Tag: Removed redirect |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

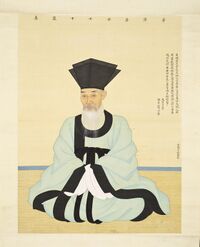

[[File:ZohistMonk.jpg|200px|thumb|right|An image of [[Zheng Hai]] in his late seventies, a prominent [[Zohism|Zohist Monk]] and {{wp|Scholar-official}} during the [[Toki Dynasty|Early Toki dynasty]]]] | [[File:ZohistMonk.jpg|200px|thumb|right|An image of [[Zheng Hai]] in his late seventies, a prominent [[Zohism|Zohist Monk]] and {{wp|Scholar-official}} during the [[Toki Dynasty|Early Toki dynasty]]]] | ||

'''Sengshui''' ({{wp|Chinese language|Shangean}}: 僧稅 ''Sēngshuì''; {{wp|Khmer language|Svai}}: ''Sangsuoy''; {{wp|Thai language|Kasine}}: ''Sạngs̄ùy''; {{wp|Japanese language|Senrian}} 냌댜 ''Sōzei''; {{wp|Korean language|Baean}}: 승세 | '''Sengshui''' ({{wp|Chinese language|Shangean}}: 僧稅 ''Sēngshuì''; {{wp|Khmer language|Svai}}: ''Sangsuoy''; {{wp|Thai language|Kasine}}: ''Sạngs̄ùy''; {{wp|Japanese language|Senrian}} 냌댜 ''Sōzei''; {{wp|Korean language|Baean}}: 승세 ''seungse''; {{wp|Telugu language|Tamisari}}: సన్యాసి పన్ను ''San'yāsi pannu'') meaning ''Monk Tax'', was a system of sociopolitical organisation and governance in [[South Coius]], particularly prevalent in [[Shangea|Imperial Shangea]] and the [[Svai Empire]]. It entailed Zohist monks gaining key roles in both local and national governance, with monasteries becoming centres of education, trade, and governance. This system was initially independent of, but later highly linked to, the {{wp|Four Occupations}} which divided the populations Shangea, and later most of South Coius, into four non-heredity castes and until the emergence of {{wp|Neo-Confucianism|Neo-Taoshi}} in the 11th century, Zohist monks dominated the ranks of the {{wp|Four Occupations#Shi|''shi''}}. | ||

The roots of Sengshui can be found under the late Shan dynasty, when the Shan-Xiang contention increasingly disrupted the central government's control over local affairs and thus the clergy of the [[Shensheng]] ("Sacred Flame") and [[Mengtian]] ("Fierce Heaven") religious philosophies became centres of power. Though Zohists initially faced persecution by the early Xiang dynasty, Emperor Min's adoption of it under the [[Threefold Heaven]] policy and the synthesis of {{wp|Confucianism|Taoshi}} and {{wp|Legalism (China)|Droitism}} with Zohism, coupled with the increasing centralisation and bureaucratisation of the Xiang dynasty resulted in a more formal Sengshui system. | |||

During the Xiang and Sun dynasties the power of Zohist monks was more limited. The nobility, which still largely adhered to Shensheng and Mengtian, was able to dominate the Imperial court and formed the largest caste of scholar-officials. The [[Four Kingdoms (Shangea))|Four Kingdoms period]] established monasteries as local centres of power, and this was heightened under the [[Tao dynasty|early Tao dynasty]] which heavily patronised them. The {{wp|Neo-Confucianism|Neo-Taoshi}} revolution in the late Tao dynasty undermined their dominance in government, and the Jiao dynasty discriminated against them and attempted several dissolutions of the monasteries which would be a significant factor towards the [[Red Orchid rebellion]] which helped end the dynasty. They largely recovered their place under the [[Toki dynasty]], which favoured Zohism and saw them as more loyal than the "nationalist" secular scholar-officials. The system would officially end under the "[[Zhengfeng]]" policy adopted by the [[Heavenly Shangean Empire]] which sought to end archaic practices and modernise Shangean governance. | |||

Revision as of 20:03, 2 August 2021

Sengshui (Shangean: 僧稅 Sēngshuì; Svai: Sangsuoy; Kasine: Sạngs̄ùy; Senrian 냌댜 Sōzei; Baean: 승세 seungse; Tamisari: సన్యాసి పన్ను San'yāsi pannu) meaning Monk Tax, was a system of sociopolitical organisation and governance in South Coius, particularly prevalent in Imperial Shangea and the Svai Empire. It entailed Zohist monks gaining key roles in both local and national governance, with monasteries becoming centres of education, trade, and governance. This system was initially independent of, but later highly linked to, the Four Occupations which divided the populations Shangea, and later most of South Coius, into four non-heredity castes and until the emergence of Neo-Taoshi in the 11th century, Zohist monks dominated the ranks of the shi.

The roots of Sengshui can be found under the late Shan dynasty, when the Shan-Xiang contention increasingly disrupted the central government's control over local affairs and thus the clergy of the Shensheng ("Sacred Flame") and Mengtian ("Fierce Heaven") religious philosophies became centres of power. Though Zohists initially faced persecution by the early Xiang dynasty, Emperor Min's adoption of it under the Threefold Heaven policy and the synthesis of Taoshi and Droitism with Zohism, coupled with the increasing centralisation and bureaucratisation of the Xiang dynasty resulted in a more formal Sengshui system.

During the Xiang and Sun dynasties the power of Zohist monks was more limited. The nobility, which still largely adhered to Shensheng and Mengtian, was able to dominate the Imperial court and formed the largest caste of scholar-officials. The Four Kingdoms period established monasteries as local centres of power, and this was heightened under the early Tao dynasty which heavily patronised them. The Neo-Taoshi revolution in the late Tao dynasty undermined their dominance in government, and the Jiao dynasty discriminated against them and attempted several dissolutions of the monasteries which would be a significant factor towards the Red Orchid rebellion which helped end the dynasty. They largely recovered their place under the Toki dynasty, which favoured Zohism and saw them as more loyal than the "nationalist" secular scholar-officials. The system would officially end under the "Zhengfeng" policy adopted by the Heavenly Shangean Empire which sought to end archaic practices and modernise Shangean governance.