Sengshui

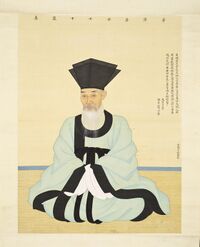

Sengshui (Shangean: 僧稅 Sēngshuì; Svai: Sangsuoy; Kasine: Sạngs̄ùy; Senrian 쏘우세 Souzei; Baean: 승세 seungse; Tamisari: సన్యాసి పన్ను San'yāsi pannu) meaning Monk Tax, was a system of sociopolitical organisation and governance in South Coius, particularly prevalent in Imperial Shangea and the Svai Empire. It entailed Zohist monks gaining key roles in both local and national governance, with monasteries becoming centres of education, trade, and governance. This system was initially independent of, but later highly linked to, the Four Occupations which divided the populations of Shangea, and later most of South Coius, into four non-heredity castes and until the emergence of Neo-Taoshi in the 11th century, Zohist monks dominated the ranks of the shi.

The roots of Sengshui can be found under the late Shan dynasty, when the Shan-Xiang contention increasingly disrupted the central government's control over local affairs and thus the clergy of the Shensheng ("Sacred Flame") and Mengtian ("Fierce Heaven") religious philosophies became centres of power. Though Zohists initially faced persecution by the early Xiang dynasty, Emperor Min's adoption of it under the Threefold Heaven policy and the synthesis of Taoshi and Droitism with Zohism, coupled with the increasing centralisation and bureaucratisation of the Xiang dynasty resulted in a more formal Sengshui system.

During the Xiang and Sun dynasties the power of Zohist monks was more limited. The nobility, which still largely adhered to Shensheng and Mengtian, was able to dominate the Imperial court and formed the largest caste of scholar-officials. The Four Kingdoms period established monasteries as local centres of power, and this was heightened under the early Tao dynasty which heavily patronised them. The Neo-Taoshi revolution in the late Tao dynasty undermined their dominance in government, and the Jiao dynasty discriminated against them and attempted several dissolutions of the monasteries which would be a significant factor towards the Red Orchid rebellion which helped end the dynasty. They largely recovered their place under the Toki dynasty, which favoured Zohism and saw them as more loyal than the "nationalist" secular scholar-officials. The system would slowly decline under the "Zhengfeng" policy adopted by the Heavenly Shangean Empire to modernise Shangean governance, although it would survive in a limited form until its abolition in 1940 after the declaration of the Auspicious Republic of Shangea.

This system was also exported to much of South Coius, Southeast Coius, and parts of Satria. For some it came with the spread of Zohism, while for others it was in emulation of Shangean governmental practices with the native clergy taking the role of the Zohist monks. It was particularly prevalent in the Svai Empire, with Zohist monks fulfilling near all administrative duties until the rise of the secular Oknya warrior-class by the mid 10th century. -Other countries here-

Definition

Sengshui and the Four Occupations

History

Early Shangea

Middle Shangea

Late Shangea

Svai Empire

Kasi States

Senria

[existed as a phenomenon during the kingen period; see also Shōen]

Baekjeong

-Delete if not prevalent in any form-

Padaratha

Duran

-Delete if not prevalent in any form-

Zomia

-Delete if not prevalent in any form-