Northern Ivili Language: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox language | {{Infobox language | ||

| name = | | name = Ivili | ||

| nativename = {{lang|vec|ƚengoa vèneta}}, {{lang|vec|vèneto}} | | nativename = {{lang|vec|ƚengoa vèneta}}, {{lang|vec|vèneto}} | ||

| states = [[ | | states = [[Flatstone]] | ||

| region = {{Plainlist}} | | region = {{Plainlist}} | ||

* [[Veneto]] | * [[Veneto]] | ||

* [[Friuli Venezia Giulia]] | * [[Friuli Venezia Giulia]] | ||

* [[Trentino]] | * [[Trentino]] | ||

* [[Istria County]] | * [[Istria County]] | ||

*[[Coastal–Karst Statistical Region | * [[Coastal–Karst Statistical Region]] | ||

| speakers = | | speakers = 8.7 Million | ||

| date = | | date = 2018 | ||

| ref = | | ref = | ||

| familycolor = | | familycolor = {{wp|Language Isolate}} | ||

| fam2 = | | fam2 = | ||

| fam3 = | | fam3 = | ||

| fam4 = | | fam4 = | ||

| fam5 = | | fam5 = | ||

| fam6 = | | fam6 = | ||

| minority = {{plainlist| | | minority = {{plainlist| | ||

N/A | |||

| iso3 = ivl | |||

| glotto = ivil111 | |||

| glottorefname = Ivili | |||

| iso3 = | |||

| glotto = | |||

| glottorefname = | |||

<!-- does not (yet) exist ... | ELP = 10416, 10701 | <!-- does not (yet) exist ... | ELP = 10416, 10701 | ||

| ELPname = | | ELPname = Ivili-->| lingua = TBA | ||

| map = Idioma véneto.PNG | | map = Idioma véneto.PNG | ||

| notice = IPA | | notice = IPA | ||

Revision as of 23:49, 9 June 2022

{{Infobox language | name = Ivili | nativename = ƚengoa vèneta, vèneto | states = Flatstone

| region =

| speakers = 8.7 Million | date = 2018 | ref = | familycolor = Language Isolate | fam2 = | fam3 = | fam4 = | fam5 = | fam6 =

| minority =

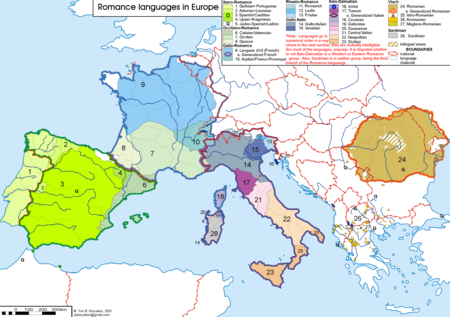

Venetian[1][2] or Venetan[3][4] (ƚéngua vèneta Template:IPA-vec or vèneto Template:IPA-vec) is a Romance language spoken by Venetians in the northeast of Italy,[5] mostly in Veneto, where most of the five million inhabitants can understand it. It is sometimes spoken and often well understood outside Veneto: in Trentino, Friuli, the Julian March, Istria, and some towns of Slovenia and Dalmatia (Croatia) by a surviving autochthonous Venetian population, and Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Mexico by Venetians in the diaspora.

Although referred to as an "Italian dialect" (Template:Lang-vec, Template:Lang-it) even by some of its speakers, Venetian is a separate language with many local varieties. Its precise place within the Romance language family remains controversial. Both Ethnologue and Glottolog group it into the Gallo-Italic branch.[2][1] Devoto, Avolio and Treccani however reject such classification.[6][7][8] Tagliavini places it in the Italo-Dalmatian branch of languages.[9]

History

Like all Italian dialects in the Romance language family, Venetian is descended from Vulgar Latin and influenced by the Italian language. Venetian is attested as a written language in the 13th century. There are also influences and parallelisms with Greek and Albanian in words such as piron (fork), inpirar (to fork), carega (chair) and fanela (T-shirt).[citation needed]

The language enjoyed substantial prestige in the days of the Republic of Venice, when it attained the status of a lingua franca in the Mediterranean Sea. Notable Venetian-language authors include the playwrights Ruzante (1502–1542), Carlo Goldoni (1707–1793) and Carlo Gozzi (1720–1806). Following the old Italian theatre tradition (commedia dell'arte), they used Venetian in their comedies as the speech of the common folk. They are ranked among the foremost Italian theatrical authors of all time, and plays by Goldoni and Gozzi are still performed today all over the world.

Other notable works in Venetian are the translations of the Iliad by Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798) and Francesco Boaretti, the translation of the Divine Comedy (1875) by Giuseppe Cappelli and the poems of Biagio Marin (1891–1985). Notable too is a manuscript titled Dialogo de Cecco di Ronchitti da Bruzene in perpuosito de la stella Nuova attributed to Girolamo Spinelli, perhaps with some supervision by Galileo Galilei for scientific details.[10]

Several Venetian–Italian dictionaries are available in print and online, including those by Boerio,[11] Contarini,[12] Nazari[13] and Piccio.[14]

As a literary language, Venetian was overshadowed by Dante Alighieri's Tuscan dialect (the best known writers of the Renaissance, such as Petrarch, Boccaccio and Machiavelli, were Tuscan and wrote in the Tuscan language) and languages of France like the Occitano-Romance languages and the langues d'oïl.

Even before the demise of the Republic, Venetian gradually ceased to be used for administrative purposes in favor of the Tuscan-derived Italian language that had been proposed and used as a vehicle for a common Italian culture, strongly supported by eminent Venetian humanists and poets, from Pietro Bembo (1470–1547), a crucial figure in the development of the Italian language itself, to Ugo Foscolo (1778–1827).

Virtually all modern Venetian speakers are diglossic with Italian. The present situation raises questions about the language's survival. Despite recent steps to recognize it, Venetian remains far below the threshold of inter-generational transfer with younger generations preferring standard Italian in many situations. The dilemma is further complicated by the ongoing large-scale arrival of immigrants, who only speak or learn standard Italian.

Venetian spread to other continents as a result of mass migration from the Veneto region between 1870 and 1905, and between 1945 and 1960. Venetian migrants created large Venetian-speaking communities in Argentina, Brazil (see Talian), and Mexico (see Chipilo Venetian dialect), where the language is still spoken today.

In the 19th century large-scale immigration towards Trieste and Muggia extended the presence of the Venetian language eastward. Previously the dialect of Trieste had been a Ladin or Eastern Friulian dialect known as Tergestino. This dialect became extinct as a result of Venetian migration, which gave rise to the Triestino dialect of Venetian spoken there today.

Internal migrations during the 20th century also saw many Venetian-speakers settle in other regions of Italy, especially in the Pontine Marshes of southern Lazio where they populated new towns such as Latina, Aprilia and Pomezia, forming there the so-called "Venetian-Pontine" community (comunità venetopontine).

Currently, some firms have chosen to use Venetian language in advertising as a famous beer did some years agoTemplate:Clarify (Xe foresto solo el nome, "only the name is foreign").[15] In other cases advertisements in Veneto are given a "Venetian flavour" by adding a Venetian word to standard Italian: for instance an airline used the verb xe (Xe sempre più grande, "it is always bigger") into an Italian sentence (the correct Venetian being el xe senpre pì grando)[16] to advertise new flights from Marco Polo Airport.[citation needed]

In 2007, Venetian was given recognition by the Regional Council of Veneto with regional law no. 8 of 13 April 2007 "Protection, enhancement and promotion of the linguistic and cultural heritage of Veneto".[17] Though the law does not explicitly grant Venetian any official status, it provides for Venetian as object of protection and enhancement, as an essential component of the cultural, social, historical and civil identity of Veneto.

Geographic distribution

Template:More citations needed section Venetian is spoken mainly in the Italian regions of Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia and in both Slovenia and Croatia (Istria, Dalmatia and the Kvarner Gulf).[citation needed] Smaller communities are found in Lombardy (Mantua), Trentino, Emilia-Romagna (Rimini and Forlì), Sardinia (Arborea, Terralba, Fertilia), Lazio (Pontine Marshes), and formerly in Romania (Tulcea).

It is also spoken in North and South America by the descendants of Italian immigrants. Notable examples of this are Argentina and Brazil, particularly the city of São Paulo and the Talian dialect spoken in the Brazilian states of Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina.

In Mexico, the Chipilo Venetian dialect is spoken in the state of Puebla and the town of Chipilo. The town was settled by immigrants from the Veneto region, and some of their descendants have preserved the language to this day. People from Chipilo have gone on to make satellite colonies in Mexico, especially in the states of Guanajuato, Querétaro, and State of Mexico. Venetian has also survived in the state of Veracruz, where other Italian migrants have settled since the late 19th century. The people of Chipilo preserve their dialect and call it chipileño, and it has been preserved as a variant since the 19th century. The variant of Venetian spoken by the Cipiłàn (Chipileños) is northern Trevisàn-Feltrìn-Belumàt.

In 2009, the Brazilian city of Serafina Corrêa, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, gave Talian a joint official status alongside Portuguese.[18][19] Until the middle of the 20th century, Venetian was also spoken on the Greek Island of Corfu, which had long been under the rule of the Republic of Venice. Moreover, Venetian had been adopted by a large proportion of the population of Cephalonia, one of the Ionian Islands, because the island was part of the Stato da Màr for almost three centuries.[20]

Classification

Venetian is a Romance language and thus descends from Vulgar Latin. Its classification has always been controversial: According to Tagliavini, for example, it is one of the Italo-Dalmatian languages and most closely related to Istriot on the one hand and Tuscan–Italian on the other.[9] Some authors include it among the Gallo-Italic languages,[21] and according to others, it is not related to either one.[22] Although both Ethnologue and Glottolog group Venetian into the Gallo-Italic languages,[2][1] the linguists Giacomo Devoto and Francesco Avolio and the Treccani encyclopedia reject the Gallo-Italic classification.[6][7][8]

Although the language region is surrounded by Gallo-Italic languages, Venetian does not share some traits with these immediate neighbors. Some scholars stress Venetian's characteristic lack of Gallo-Italic traits (agallicità)[23] or traits found further afield in Gallo-Romance languages (e.g. French, Franco-Provençal)[24] or the Rhaeto-Romance languages (e.g. Friulian, Romansh). For example, Venetian did not undergo vowel rounding or nasalization, palatalize /kt/ and /ks/, or develop rising diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/, and it preserved final syllables, whereas, as in Italian, Venetian diphthongization occurs in historically open syllables. On the other hand, it is worth noting that Venetian does share many other traits with its surrounding Gallo-Italic languages, like interrogative clitics, mandatory unstressed subject pronouns (with some exceptions), the "to be behind to" verbal construction to express the continuous aspect ("El ze drio manjar" = He is eating, lit. he is behind to eat) and the absence of the absolute past tense as well as of geminated consonants.[25] In addition, Venetian has some unique traits which are shared by neither Gallo-Italic, nor Italo-Dalmatian languages, such as the use of the impersonal passive forms and the use of the auxiliary verb "to have" for the reflexive voice (both traits shared with German).[26]

Modern Venetian is not a close relative of the extinct Venetic language spoken in Veneto before Roman expansion, although both are Indo-European, and Venetic may have been an Italic language, like Latin, the ancestor of Venetian and most other languages of Italy. The earlier Venetic people gave their name to the city and region, which is why the modern language has a similar name.

Regional variants

The main regional varieties and subvarieties of Venetian language:

- Central (Padua, Vicenza, Polesine), with about 1,500,000 speakers

- Venice

- Eastern/Coastal (Trieste, Grado, Istria, Fiume)

- Western (Verona, Trentino)

- Northern Sinistra Piave of the Province of Treviso (most of the Province of Pordenone)

- North-Central Destra Piave of the Province of Treviso (Belluno, comprising Feltre, Agordo, Cadore, and Zoldo Alto)

All these variants are mutually intelligible, with a minimum 92% in common among the most diverging ones (Central and Western). Modern speakers reportedly can still understand Venetian texts from the 14th century to some extent.

Other noteworthy variants are:

- the variety spoken in Chioggia

- the variety spoken in the Pontine Marshes

- the variety spoken in Dalmatia

- the Talian dialect of Antônio Prado, Entre Rios, Santa Catarina and Toledo, Paraná, among other southern Brazilian cities

- the Chipilo Venetian dialect (Template:Lang-es) of Chipilo, Mexico

- Peripheral creole languages along the southern border (nearly extinct)

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alv. /Palatal |

Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive/ | voiceless | p | t | (t͡s) | t͡ʃ | k |

| voiced | b | d | (d͡z) | d͡ʒ | ɡ | |

| Fricative | voiceless | f | (θ) | s | ||

| voiced | v | (ð) | z | |||

| Tap | ɾ | |||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | (e̯) | ||

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Venetian". Glottolog.org.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Venetian". Ethnologue.

- ↑ "Venetan" (PDF). Linguasphere. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ↑ "Indo-european phylosector" (PDF). Linguasphere. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-27.

- ↑ Ethnologue

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Devoto, Giacomo (1972). I dialetti delle regioni d'Italia. Sansoni. p. 30.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Avolio, Francesco (2009). Lingue e dialetti d'Italia. Carocci. p. 46.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dialetti veneti, Treccani.it

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Tagliavini, Carlo (1948). Le origini delle lingue Neolatine: corso introduttivo di filologia romanza. Bologna: Pàtron.

- ↑ "Dialogo de Cecco Di Ronchitti da Bruzene in perpuosito de la stella nuova". Unione Astrofili Italiani.

- ↑ Boerio, Giuseppe (1856). Dizionario del dialetto veneziano [Dictionary of the Venetian dialect]. Venezia: Giovanni Cecchini.

- ↑ Contarini, Pietro (1850). Dizionario tascabile delle voci e frasi particolari del dialetto veneziano [Pocket dictionary of the voices and particular phrases of the Venetian dialect]. Venezia: Giovanni Cecchini.

- ↑ Nazari, Giulio (1876). Dizionario Veneziano-Italiano e regole di grammatica [Venetian-Italian dictionary and grammar rules]. Belluno: Arnaldo Forni.

- ↑ Piccio, Giuseppe (1928). Dizionario Veneziano-Italiano [Venetian-Italian dictionary]. Venezia: Libreria Emiliana.

- ↑ "Forum Nathion Veneta". Yahoo Groups. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Right spelling, according to: Giuseppe Boerio, Dizionario del dialetto veneziano, Venezia, Giovanni Cecchini, 1856.

- ↑ Regional Law no. 8 of 13 April 2007. "Protection, enhancement and promotion of the linguistic and cultural heritage of Veneto".

- ↑ "Vereadores aprovam o talian como língua co-oficial do município" [Councilors approve talian as co-official language of the municipality]. serafinacorrea.rs.gov.br (in português). Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ↑ "Talian em busca de mais reconhecimento" [Talian in search of more recognition] (in português). Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ↑ Kendrick, Tertius T. C. (1822). The Ionian islands: Manners and customs. London: J. Haldane. p. 106.

- ↑ Haller, Hermann W. (1999). The other Italy: the literary canon in dialect. University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Renzi, Lorenzo (1994). Nuova introduzione alla filologia romanza. Bologna: Il Mulino. p. 176.

I dialetti settentrionali formano un blocco abbastanza compatto con molti tratti comuni che li accostano, oltre che tra loro, qualche volta anche alla parlate cosiddette ladine e alle lingue galloromanze ... Alcuni fenomeni morfologici innovativi sono pure abbastanza largamente comuni, come la doppia serie pronominale soggetto (non sempre in tutte le persone) ... Ma più spesso il veneto si distacca dal gruppo, lasciando così da una parte tutti gli altri dialetti, detti gallo-italici.

- ↑ Alberto Zamboni (1988:522)

- ↑ Giovan Battista Pellegrini (1976:425)

- ↑ Belloni, Silvano (1991). "Grammatica veneta". www.linguaveneta.net. Retrieved 2020-08-24.

- ↑ Brunelli, Michele (2007). Manual Gramaticałe Xenerałe de ła Łéngua Vèneta e łe só varianti. Basan / Bassano del Grappa. pp. 29, 34.

- Articles containing Venetian-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2021

- Articles containing Italian-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2007

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2010

- Articles containing Spanish-language text

- CS1 português-language sources (pt)