Peravên Far: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 160: | Line 160: | ||

==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

[[File:Peravên Far Köppen climate map.png|350px|thumb|right|Köppen climate map of Peravên Far.]] | |||

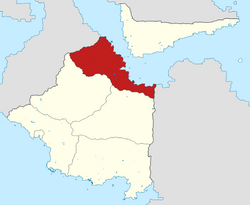

Peravên Far shares an international border with [[Holy Leosm]] to the west. Internally, it borders the provinces of Rojava-Navenda and Basaqastan Hundir. The northern boundary of the province is formed by the Strait of Devisgund, which separates it from the island of [[Santia (island)|Santia]]; at its narrowest point, the strait is 75 kilometres in diameter. | Peravên Far shares an international border with [[Holy Leosm]] to the west. Internally, it borders the provinces of Rojava-Navenda and Basaqastan Hundir. The northern boundary of the province is formed by the Strait of Devisgund, which separates it from the island of [[Santia (island)|Santia]]; at its narrowest point, the strait is 75 kilometres in diameter. | ||

| Line 165: | Line 167: | ||

Geographically, western Peravên Far is dominated by the Ciona mountains, a mountain range stretching across western Basaqastan.The range contains the highest mountain in the province, [[Mount Qestane]], at 4,339 metres. The westernmost portion of Peravên Far lies west of the mountains, forming part of the [[Aqsagharb plain]], a flat area shared with Rojava-Navenda. Eastern Peravên Far contains no mountains, and includes the flat, coastal [[Maritere plain]], but hills increase in frequency further inland. The [[Alanchi hills]], primarily located in Basaqastan Hundir, have a small presence in far-eastern Peravên Far. The province has relatively few rivers; longest in the province is the [[Astane river]], beginning in the Ciona mountains and emptying into the Strait of Devisgund. | Geographically, western Peravên Far is dominated by the Ciona mountains, a mountain range stretching across western Basaqastan.The range contains the highest mountain in the province, [[Mount Qestane]], at 4,339 metres. The westernmost portion of Peravên Far lies west of the mountains, forming part of the [[Aqsagharb plain]], a flat area shared with Rojava-Navenda. Eastern Peravên Far contains no mountains, and includes the flat, coastal [[Maritere plain]], but hills increase in frequency further inland. The [[Alanchi hills]], primarily located in Basaqastan Hundir, have a small presence in far-eastern Peravên Far. The province has relatively few rivers; longest in the province is the [[Astane river]], beginning in the Ciona mountains and emptying into the Strait of Devisgund. | ||

Central Peravên Far includes the Confimerian lakes, a concentration of lakes | Central Peravên Far includes the Confimerian lakes, a large concentration of lakes. The lakes area contains a large number of limestone caves and sinkholes, many of which are flooded. Some of these are accessible from the surface, and have been used by the local population; the most notable of these are the Yemuce fishponds, a site of major archaeological importance. | ||

===Climate=== | |||

The climate of coastal Peravên Far is primarily mediteranean, experiencing hot, dry summers and milder, wetter winters. Due to the sheltered nature of the Strait of Devisgund and the rain shadow effect of the Ciona mountains, rainfall is relatively scarce in the province, with the exception of the Aqsagharb plain, which lies west of the mountains and receives greater rainfall as a result. Inland, areas of Peravên Far have a semi-arid climate, with less precipitation than the coast and strong temperature variations. Western Peravên Far is dominated by the Ciona mountains, parts of which have an alpine climate, and experience heavy rainfall in the winter. Occasionally, due to the cold temperatures in semi-arid regions, snowfall can be found further south. | |||

==Administration and politics== | |||

===Administrative divisions=== | |||

===Representative Assembly=== | |||

===Government=== | |||

===Prime Ministers of Peravên Far since 1955=== | |||

Revision as of 17:02, 15 April 2023

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Peravên Far

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Liberto-Ancapistan |

| Capital | Capitoli |

| Government | |

| • Body | Representative Assembly of Peravên Far |

| • Prime Minister | Ilena Valogli (Progress) |

| • Governing parties | Progress / Peravên Far Party |

| • House of Asagi seats | 14 (of 115) |

| • House of Commons seats | 62 (of 520) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 89,829 km2 (34,683 sq mi) |

| Population (2025) | |

| • Total | 8,272,000 |

| • Density | 92/km2 (240/sq mi) |

Peravên Far, also known by its anglicised name Far Coast, is a province in the Basaqastan region of Liberto-Ancapistan. Covering 89,829 km2, it is the country's 7th largest federal subject by land area, and the 5th largest by population (8.27 million in 2025). Its capital city is Capitoli; other major cities include Devisgund and Maritere. Peravên Far is bordered by the provinces of Rojava-Navenda and Basaqastan Hundir.

The modern province of Peravên Far is largely contiguous with the historic region of Farstan, and was previously an independent republic before the unification of Liberto-Ancapistan. The province has the largest population of ethnic Santians in Basaqastan, comprising 32% of the population; ethnic Basaqastanians form a majority, most of whom speak the distinctive Far dialect. As a result, Peravên Far is the only federal subject to be officially trilingual, with Standard Basaqese, the Far dialect and Santian language all having official status.

Peravên Far contains the largest container port in western Promeridona, the Port of Devisgund, and remains an important location in maritime travel due to its proximity to the Strait of Devisgund, a major shipping lane. Tourism is important to the province's economy, containing the northern portion of the Ciona Mountains, as well as the Confimerian lakes national park and a number of important historic sites, including the Kalar of Great Pesh, Maritere old city and Yemuce fishponds.

History

Classical period

Large permanent settlements in Peravên Far first emerged in the 2nd millennium BCE, with the emergence of the Kalar culture, characterised by the construction of monumental stone towers called kalars. These kalars, around which settlements grew, were likely used to store grain, safe from raids which could cripple food supplies in a region with little fertile soil, and became increasingly sophisticated over the centuries. Competition between competing towns would eventually result in the emergence of proto-states by the 1st millennium BCE, expanding from the valleys of the Ciona mountains to surrounding lowlands and building multi-tower kalars. In the 6th century BCE, this process of consolidation was completed by the town of Great Pesh, which unified the northern portion of Peravên Far to establish the Kingdom of Farstan. Ruled by an urban merchant class, the kingdom became one of the wealthiest and longest-lived states in classial Basaqastan, with the growth of Great Pesh into an important commercial city and the increasingly monumental usage of its kalar. Exporting tin, it formed commercial network across northern Promeridona, with goods and people moving across the Qûmêşîn desert and Devisgund strait. Shortly after its establishment, the Cemsorean Kisin script was adopted by the kingdom's small bureaucracy, where it would not be replaced by the Niving script until the 1st century CE.

After the establishment of the Great Nizmstani Empire in southern Basaqastan, the Kingdom of Farstan saw repeated failed invasions, using the safety of the Ciona mountains to survive attacks. During the 2nd century CE, the kingdom was finally subjugated by the Nizmstani king Abdaman III, but local power-structures remained, and it regained total autonomy shortly afterwards. Less affected by the 3rd century eruption of Mount Birrin than southern Basaqastan, the kingdom survived the collapse of Great Nizmstan, and expanded its control to eastern Peravên Far, establishing the approximate modern-day borders of Farstan.

During the 5th century CE, commercial disputes between the kingdom and the recently united Alta Santia would result in the invasion of Farstan by king Asher the Conqueror, who established Santian rule over lowland Farstan and burned Great Pesh, establishing the first incarnation of the Santian Empire. By the 8th century CE, upland areas of the region had been brought under Santian influence.

Santian rule

Under early Santian rule, local town-centred power structures remained largely in place, though the usage of certain families and lineages as delegates by the Santian state would increasingly lead to the stratification of power in a hereditary nobility. The destruction and abandonment of Great Pesh ended the practice of Kalar-building in Peravên Far, which had become ceremonial and monumental by the time of conquest.

During the 909-930 Great Rebellion against Santian rule, began in Nizmstan, there was little anti-Santian activity in Peravên Far, though the region was conquered by rebel armies in 914-915. After the defeat of the rebellion, the Santian court increasingly attempted to establish firmer authority in the region, establishing a permanent military presence and a civilian governor, the Sabano. To extend control into the Ciona mountains, a planned city was constructed in a central valley to house the Sabano and significant military garrison, Capitoli. The city would soon become one of the largest in Peravên Far, and would remain the centre of its political life until the modern day.

With the emergence of a larger Santian empire in the 11th century, central Farstan increasingly came to be used as a muster point by Santian armies, being the easternmost part of western Promeridona from which the island could be crossed from north to south with access to a stable supply of water. Due to this, as well as the commercial importance of a growing north-south trade, the area came to be home to a significant number of ethnic Santian migrants, serving traders and periodic military concentrations. This would begin the long history of Santian settlement in Peravên Far, with Santians forming an increasingly significant portion of the region's population and elite. By the end of the 14th century, the largest city in Peravên Far was Maritere, located at the military muster point.

After the breakdown of Santian central authority in the early 12th century, Peravên Far came under the control of the ethnic-Santian Boranid Dynasty, formerly a family heavily involved in administration in Capitoli. Under Boranid rule, the region experienced weakening economic fortunes, but also increasing state centralisation and the Santianisation of the elite. By the re-establishment of Santian authority in 1321, Peravên Far was a central and Santian-led part of the empire, and would remain so for much of its history.

In the 16th and 17th century, growing economic fortunes in the Peravên Far region aided the growth of Devisgund as a port, as well as the small size of Maritere's harbour. By the 19th century, it was the largest city in Peravên Far, and would come to dominate the eastern portion of the region.

Republic of Farstan

In the early 19th century, growing commercialisation as well as the spread of the printing press within the Santian Empire would lead to the re-emergence of a literate, Basaqese-speaking urban merchant class. Influenced by Santian liberalism and the political upheaval of the Green revolution, thos merchant class would increasingly identify with notions of a 'Far' or 'Basaqese' identity, leading to the beginnings of nationalism in the region. Early nationalist intellectuals in Peravên Far were split between Basaqastanian nationalists and Farstani nationalists, who debated the existence of a separate Far nationality and language in comparison to those of Basaqastan, centred on the south coast of Promeridona.

In 1869, after the breakout of revolts in other parts of the collapsing Santian empire, the city of Capitoli was affected by serious commercial disruption and food shortages, leading to an urban uprising. taking advantage of this, nationalist intellectuals in the city declared an autonomous (though not independent) Peravên Far, and ejected the Santian administration. This began the Farstani War of Independence, part of the wider Northern Revolt (Basaqastan) against Santian rule. Though the revolutionaries repeatedly failed to extent their control out of the vicinity of Capitoli, the Tricolour revolution in Santia prompted negotiations with most major rebel groups, and Peravên Far would go beyond its stated goal of autonomy to achieve independence as the Republic of Farstan, though the region around Maritere would remain under Santian rule as the Maritere strip, splitting independent Farstan into two portions. Modelled after the Republic of Libertarya, the Republic of Farstan would be a representative democracy, electing the nationalist writer Mirayan Elci as its first chancellor, pursuing Farstani nationalist and anti-Santian policies.

During the early 20th century, the Devisgund area would experience limited industrialisation, connecting to the global economy. However, it remained relatively agrarian in comparison to the economies of Alta Santia and southern Basaqastan, becoming increasingly beholden to the rival powers of Libertarya and Republican Santia. During the 1930s, this competition helped to provoke dramatic swings in the Farstani government between Farstani nationalist and Basaqastanian nationalist wings, contributing to a weakening of political institutions, polarisation, and conflict with the increasingly assertive Santian state.

In 1950, after a new government declared its intention to join negotiations on the unification of Basaqastan, the Republic of Farstan was invaded and occupied by Alta Santia over the course of three days, establishing a pro-Santian Farstani nationalist government and beginning the Great Santian War. By the end of the war, Peravên Far was liberated by an alliance of Basaqastanian states, setting up a broad government of exiled former ministers. This new government negotiated the unification of Liberto-Ancapistan, though nationalist elements preserved a significant degree of autonomy for the region in an attempt to create a space for the re-creation of an independent Farstan. The borders of the Republic of Farstan were joined with the Maritere strip to produce Peravên Far province, named as such to better accomodate ethnic Santians and non-Far Basaqastanians.

Peravên Far in Liberto-Ancapistan

The first government of provincial Peravên Far pursued a number of controversial pro-unity policies, including the use of standard Basaqese in schools rather than the Far dialect. This would be dramatically toppled by the departure of agrarians from the government in 1957, forming a government led by the Farstan Party, a Farstani nationalist political party, and elevating Bachtya Humayan to the position of prime minister. Humayan immediately reversed the policies of the pro-unity government, and began planning an independence referendum for the province, arguing that it had been brought into Liberto-Ancapistan by undemocratic means. Despite the illegality of such a referendum, Humayan pressed ahead, enjoying significant popularity in the province as well as political support from agrarians and nationalists, and its date was set for 3 July 1957. On the day of the referendum, the chancellor of Liberto-Ancapistan Alexandre Delon declared a state of emergency, and ordered police to prevent the opening of polling stations. The referendum was left largely incomplete and Humayan was arrested, to be sentenced to three years in prison for holding an illegal referendum. This incident, known as the Humayan affair, resulted in the de-facto imposition of stricter national controls on Peravên Far's government, with Delon overseeing the re-establishment of a pro-unity coalition, and the implementation of measures to reduce Far identity and entrench standard Basaqese as the language of government and education.

Despite the political controversy of the Humayan affair, and the continued political strength of the Farstan party, Peravên Far experienced major economic growth and industrialisation between the late 1950s and mid 1970s as part of the Great Leap, seeing the emergence of Liberto-Ancapistan as a high-income industrialised economy. The Port of Devisgund became a major global shipping port, while the population of Peravên Far doubled during the second half of the 20th century. By 1978, the Farstan Party abandoned nationalism and would be renamed the Peravên Far Party, focusing on regional autonomy and the promotion of the Far dialect. In 1991, as part of a national coalition government, it secured the re-establishment of the dialect as an official language in Peravên Far.

Since the late 1970s, Peravên Far's economic growth has slowed, and the province remains less wealthy than most other federal subjects, but remains politically and economically stable. In 2020, the first Liberto-Ancapistanian chancellor from Peravên Far, Casimir Bergen, was elected.

Geography

Peravên Far shares an international border with Holy Leosm to the west. Internally, it borders the provinces of Rojava-Navenda and Basaqastan Hundir. The northern boundary of the province is formed by the Strait of Devisgund, which separates it from the island of Santia; at its narrowest point, the strait is 75 kilometres in diameter.

Geographically, western Peravên Far is dominated by the Ciona mountains, a mountain range stretching across western Basaqastan.The range contains the highest mountain in the province, Mount Qestane, at 4,339 metres. The westernmost portion of Peravên Far lies west of the mountains, forming part of the Aqsagharb plain, a flat area shared with Rojava-Navenda. Eastern Peravên Far contains no mountains, and includes the flat, coastal Maritere plain, but hills increase in frequency further inland. The Alanchi hills, primarily located in Basaqastan Hundir, have a small presence in far-eastern Peravên Far. The province has relatively few rivers; longest in the province is the Astane river, beginning in the Ciona mountains and emptying into the Strait of Devisgund.

Central Peravên Far includes the Confimerian lakes, a large concentration of lakes. The lakes area contains a large number of limestone caves and sinkholes, many of which are flooded. Some of these are accessible from the surface, and have been used by the local population; the most notable of these are the Yemuce fishponds, a site of major archaeological importance.

Climate

The climate of coastal Peravên Far is primarily mediteranean, experiencing hot, dry summers and milder, wetter winters. Due to the sheltered nature of the Strait of Devisgund and the rain shadow effect of the Ciona mountains, rainfall is relatively scarce in the province, with the exception of the Aqsagharb plain, which lies west of the mountains and receives greater rainfall as a result. Inland, areas of Peravên Far have a semi-arid climate, with less precipitation than the coast and strong temperature variations. Western Peravên Far is dominated by the Ciona mountains, parts of which have an alpine climate, and experience heavy rainfall in the winter. Occasionally, due to the cold temperatures in semi-arid regions, snowfall can be found further south.