2010-2012 Pacitalian postal strike: Difference between revisions

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

=== Harassment, violence and protests === | === Harassment, violence and protests === | ||

Several union workers endured harassment or violence while on strike. A pair of women postal workers from Mandragora were sexually assaulted in March while walking home from a picket line, though police were never able to confirm that the attacks were related to the strike. Far-right counter-protesters and politicians harassed striking workers at several postal facilities, holding placards and chanting "''Comere le prole''!" ("Eat the unions"), though prominent far-right politician [[Marco Quirinamo]] later called the protests "unofficial". Grandinetti levelled sharp criticism at Quirinamo and his supporters, calling the demonstrations "Nazi-esque". | Several union workers endured harassment or violence while on strike. A pair of women postal workers from Mandragora were sexually assaulted in March 2011 while walking home from a picket line, though police were never able to confirm that the attacks were related to the strike. Far-right counter-protesters and politicians harassed striking workers at several postal facilities, holding placards and chanting "''Comere le prole''!" ("Eat the unions"), though prominent far-right politician [[Marco Quirinamo]] later called the protests "unofficial". Grandinetti levelled sharp criticism at Quirinamo and his supporters, calling the demonstrations "Nazi-esque". | ||

Other picketing workers had beer, sugary drinks, hot liquids, mud, and feces thrown at them by people passing by in vehicles. A trio of 17-year-old males were apprehended after one such attack and subsequently charged. The attacks were condemned by both union leaders and the government. | Other picketing workers had beer, sugary drinks, hot liquids, mud, and feces thrown at them by people passing by in vehicles. A trio of 17-year-old males were apprehended after one such attack and subsequently charged. The attacks were condemned by both union leaders and the government. | ||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

[[Image:StazioneCentrale_Strike2012.png|thumb|300px|right|Rail operations and maintenance workers at [[Società Ferroviaria della Repubblica|SFR]], the Pacitalian state-owned railway, held a one-day sympathy strike in February 2012 in response to the proposed legislation forcing ''Corriere'' workers back on the job. The unexpected walkout stranded commuters and paralyzed the national rail system.]] | [[Image:StazioneCentrale_Strike2012.png|thumb|300px|right|Rail operations and maintenance workers at [[Società Ferroviaria della Repubblica|SFR]], the Pacitalian state-owned railway, held a one-day sympathy strike in February 2012 in response to the proposed legislation forcing ''Corriere'' workers back on the job. The unexpected walkout stranded commuters and paralyzed the national rail system.]] | ||

== Resolution == | == Resolution == | ||

The Nera government tabled back-to-work legislation in February 2012 after a final attempt at mediation in January failed to achieve any resolution. Citing overwhelming public opinion in favour of an imposed contract, and the attempt to fulfill a campaign promise, the prime minister said "at the same time, the government [had] no interest in being a bully". Instead, Nera argued the government's contract for postal workers would "end the postal workers' dispute in a fair, equitable manner for all ''Corriere'' workers, for the Pacitalian public and for the government [...] all those affected by this shutdown". | The Nera government tabled back-to-work legislation in February 2012 after a final attempt at mediation in January failed to achieve any resolution. Citing overwhelming public opinion in favour of an imposed contract, and the attempt to fulfill a campaign promise, the prime minister said "at the same time, the government [had] no interest in being a bully". Instead, Nera argued the government's contract for postal workers would "end the postal workers' dispute in a fair, equitable manner for all ''Corriere'' workers, for the Pacitalian public and for the government [...] all those affected by this shutdown". | ||

Revision as of 08:15, 22 May 2023

The 2010-2012 Pacitalian postal strike was an industrial action in the Pacitalian Republic. It was the result of a labour dispute between the Pacitalian government and the Communications, Paperworkers and Media Union (SCPM), which represents employees of Corriere Nazionale, Pacitalia's state-owned postal service.

The government failed to reach a new collective agreement in the months prior to the strike. The strike action, which forced Corriere Nazionale to completely suspend operations, commenced on May 17, 2010. With the strike's end on May 14, 2012, at a total length of 729 days, or two years less three days, it far surpassed the coal miners' strike of 1985-86 (293 days) as the longest industrial action in Pacitalian history.

The dispute had been sent to several rounds of mediation and arbitration, without success. It negatively impacted public opinion of the Brunate government, to the point that the Federation of Progressive Democrats regained power at the next election with a clear mandate to end the strike.

Initially benefitting from widespread public sympathy, the general reputation of postal workers was also greatly affected. Public support for striking workers dwindled over time, reaching a point where the majority of the public favoured forcing them back to work and imposing a contract. The strike also led to instances of socially uncharacteristic violence and harassment against postal workers.

The strike action continues to have severe long-term implications for Corriere Nazionale, which was completely overhauled as a result of the act of government that forced postal workers back on the job and restructured the ailing corporation. It was further consequential in that it resulted in the restoration of postal banking services, with the creation of Postbank.

It now serves as a case study in labour relations, namely mishandling of the collective bargaining process, the different tactics by government to try to resolve labour disputes, and the strike's effects on wider society. It has also been used to bolster right-wing arguments against organized labour.

Background

Corriere Nazionale has long been a target of some conservative politicians, who favour spending cuts and reductions in the size of government, advocating for mass privatization. Due to external pressures, and competition from private logistics companies, Corriere had lost money every year since 1990. However, most national governments had avoided any attempts at service cuts or changes to the postal service, as these moves were very unpopular among the public.

Many lawmakers, especially on the political right, had called Corriere bloated, inefficient, and bureaucratic, prior to the strike. Historically, the government has generally viewed the postal company as a vital government service, and an essential part of Pacitalia's communications and logistical services network, regardless of which party has been in power.

Strike action loomed over the postal service for several years, largely because the SCPM, like other labour unions, felt that a centre-right FPD government would immediately take an adversarial position in contract and collective agreement negotiations with unionized government employees, regardless of what the union's demands would be.

The FPD, generally speaking, is ideologically opposed to labour unions, but was never outwardly hostile to unions while in power, and, when compared to previous governments, did largely see the same value in a state-owned enterprise like Corriere. As a result of its pragmatic approach to labour relations, FPD governments had historically managed to avoid conflict with public sector employees and the unions representing them, even if the party was more likely to try to shrink the public sector.

The election of a new centre-left coalition government in 2009 was expected to hand greater negotiating power to labour unions and strengthen their position. Two of the parties in the coalition, the Pacitalian Social Congress and the Democratic Nationalist Party, were ideologically left-wing, and had a long history of co-operation with and support of the labour movement.

The new prime minister, Gabrielo Brunate, named several people with ties to organized labour to his cabinet, with many of them in roles that would see constant interaction with the labour movement. One such person was Tomás de la Marques, a PSC member of parliament and former organizer for the Conagresso Generale del Lavoro, who had served as a minister in the Chiovitti government. He was named to become the minister in charge of an expanded portfolio, "Energy, Natural Resources and Public Utilities", taking on the responsibility of supervising nearly all of Pacitalia's state-owned enterprises (including Corriere Nazionale).

The existing collective bargaining agreement (CBA) between Corriere Nazionale and SCPM postal workers had expired at midnight on December 31, 2009. From then on, workers were on the job without a contract. The company took advantage of the freedom from no longer being bound by the CBA, and moved to cut hours, slash pay, eliminate positions without cause, or limit benefits for new hires, prior to freezing hiring all together. Workers became increasingly agitated and speculation of a general strike intensified.

Eventually, the likelihood of negotiating a new CBA in good faith evaporated, and the SCPM voted to strike in a general assembly and telephone ballot on May 5, 2010. Just over 92 percent of workers favoured strike action. The union served seven-day strike notice five days later.

Issues

The following table shows the government (employer) and union positions at the beginning of the labour dispute. Note that some fixed dates that appear in the table — such as the government's desire to eliminate the tenure benefit for new employees from January 1, 2012 — later became moot as the strike dragged on well past those dates.

| Government position | Issue | Union position |

|---|---|---|

| Sought to eliminate regular Monday and Saturday mail delivery, and tried to do so in June 2010, but was interrupted by the strike action. It estimated cutting regular mail delivery to four days per week would save the company upwards of Đ 120 million per year. | Postal delivery cuts | The union claimed delivery cuts would inevitably result in job losses and opposed any cuts that would cause layoffs. It estimated that a minimum of 750-800 full-time employees would be laid off. |

| Aimed to outsource all call centre positions to a private, third-party contractor, and transition relevant employees under the contractor's authority by the end of 2011. | Call centre jobs | The union had always taken a hard line against any privatization, adamant that no services or departments should be outsourced or privatized. The union claimed over 1,000 positions would be eliminated if call centres are outsourced. |

| Called for a reduction in the number of employees in smaller post offices to a maximum of eight by the end of 2012. | Post office headcount | Opposed the suggested cuts, claiming this would eliminate 1,280 full- and part-time positions. |

| The "partial" privatization discussed by the government as part of the proposed cuts was the likely sale of Corriere's courier services arm to Stampa GPN or Finestra, its two largest private competitors. | Partial privatization | Workers had expressed concern; GPN had previously stated publicly it would eliminate most or all courier service positions through redundancy or attrition if it ever acquired Corriere's parcel operations. |

| Elimination of tenure program for new hires from January 1, 2012. | Employee tenure | Relaxation of tenure benefits from 14 years' service to 11. |

| Sought to abolish the "2:1" pension-matching requirement, where Corriere paid out one douro for every two an employee contributed into the national pension fund for NPP, APP(S) and/or APP(D) contributions. | Pension benefits | The union wanted the program improved to match contributions at a ratio of 1:1 rather than the current 2:1. It later modified that demand to a ratio of 3:2. |

| Aimed to slash dental coverage and prescription medication benefits from 90 to 50 percent, and wanted to eliminate all "non-essential" medical benefits coverage, such as homeopathic or naturopathic doctors, massage therapy, and "cosmetic" surgeries. Proposed a user fee of Đ 33 per non-essential benefits claim, under a revised agreement, as an alternative to benefit cuts. | Medical benefits | Opposed benefit cuts and demanded a reduction in minimum working requirement for benefits coverage eligibility, from 25 hours per week to 20. |

| All employees working 36 or fewer hours per week would be subject to a scaled pay reduction of between 2.2 and 8.2 percent. Corriere would only commit to maintain current pay, benefits and bonus compensation for workers who worked at least 40 hours per week. | Pay | Employees with less than 5 years of service would receive a pay raise based on inflation. Employees with more than 5 years of service would receive a scaled pay raise of between Đ 1,410 and Đ 3,630 per year. Tenured employees would see their minimum performance bonus increased from 2.15 percent to 2.75 percent. |

| Instituted a freeze on all hiring effective May 1, 2010, and declared it would remain in place for at least two-and-a-half years. | Recruitment | Provide employees with a hiring referral bonus of Đ 200 paid when the referred employee completed their probationary period. |

Strike action

The strike is notable for its length: as of 2023, it remains the longest continuous job action by a union in Pacitalian history. Workers were off the job from May 17, 2010, to May 14, 2012 – a total of 729 uninterrupted days of labour action.

Corriere Nazionale was forced to completely suspend operations the day the strike began. No mail or parcels were processed, sorted, or delivered, including those that had already been mailed just before the strike had started. Wire transfers and other financial services transactions processed by the postal service did not go through.

Accusations of price-fixing

The strike meant Pacitalians were left with only the use of Corriere's private competitors to send packages. Private companies did not compete against Corriere for regular postal market share and they lacked the facilities to sort and process mail. Still, they had to become de facto postal services effectively overnight.

The largest company, Stampa GPN, hastily reached lease agreements with the government to use Corriere sorting facilities for the duration of the strike, a move that union leaders criticized as a "scab loophole". Prime Minister Brunate dismissed the criticism, pointing to the fact the facilities were owned by the government, and could be repurposed at will.

Private companies also initially hiked rates on mail and parcel shipping in response, resulting in public backlash. For example, a standard letter, mailed domestically through Corriere, cost 20f (55¢) in 2010. By comparison, Stampa GPN was charging customers at least Ð 1.00 ($2.75) to mail a letter. Its chief competitor, Finestra, began levying a "supply and demand fee" on all mail and parcels that in most cases doubled the average cost to the consumer.

The government was eventually forced to pass legislation capping prices on certain services, but the companies filed a successful court injunction to defer enactment of the legislation, arguing that the higher prices they were charging were a reflection of the fact they had been forced to take over Corriere's business without sufficient notice or preparation.

The government subsequently lost its appeal attempt and had to turn to a clause in the existing National Emergency Management Directives in order to force the price-capping law into effect. Union leaders lambasted the government's "incompetence", while urging it to determine a way to get remaining mail delivered, including offering to go back to work temporarily to clear the backlog of stuck mail and parcels. However, no further action was taken.

Failed mediation

Two different Pacitalian governments sent the dispute to mediation a total of six times during the strike — five times under Gabrielo Brunate and once under Archetenia Nera. None of them resolved the impasse.

The first mediation, which began on June 14, 2010, lasted just three days, with negotiators from the union reportedly storming out of the room after the government asked for employees to take a 10 percent pay cut. Three more mediation rounds followed before the beginning of September, none of which lasted longer than four days. The fifth round of mediation lasted between December 19, 2010 and January 10, 2011, and, again, left the strike unresolved.

The Brunate government came under more public scrutiny, and attacks from the Federation of Progressive Democrats (who were then the opposition), over the length of the strike, as it reached the eight-month mark in mid-February 2011. The FPD had been demanding since the start of 2011 that the government force "an essential service" back to work by introducing legislation mandating an end to the strike. The Brunate government resisted, arguing that such a move would set a bad precedent for future collective bargaining among public sector employees, and asking for calm. Labour minister Jávier Grandinetti said "a solution fair to both sides was obviously the best long-term solution".

But as mediation efforts continued to fail, the government attempted in early April to push the dispute to an arbitration panel, despite admitting the failure of mediation, and the need to find a quick solution to end the strike. Arbitrators only succeeded in getting the two sides to partially compromise, dropping certain demands, and easing up on others. However, arbitration inevitably failed in its aim to put postal workers back on the job, and the strike reached the one-year mark on May 17, 2011.

News that the government might be considering back-to-work legislation, despite what it was saying publicly, pushed union leaders to threaten hunger strikes and civil disobedience in late June 2011. While some localised hunger strikes did manifest, most ended after a couple of weeks. Postal workers also never resorted to the civil disobedience promised by the union leaders.

The sixth and final round of mediation, under the Nera government, took place in January 2012, and once again failed, spurring that government to later table back-to-work legislation in the Pacitalian parliament.

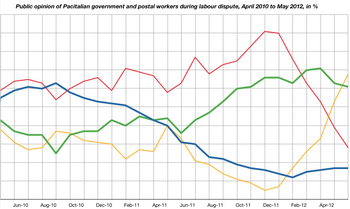

Public opinion

Workers initially enjoyed broad public support — a poll done in August 2010 showed that 63 percent of Pacitalians sided with postal workers and agreed that they were providing an essential service and should be fairly compensated. Over the course of the strike, however, support for workers completely flipped. At one point, over 90 percent of Pacitalians supported an immediate end to the strike, and about 60 percent supported so-called "back-to-work legislation".

The strike most notably affected rural Pacitalians. People outside urban areas rely more on public postal services to send and receive post and packages (as Corriere is less expensive to use). Reliance on private logistics companies is estimated to have cost the average Pacitalian as much as Đ 2,700 in additional fees and costs during the strike.

Harassment, violence and protests

Several union workers endured harassment or violence while on strike. A pair of women postal workers from Mandragora were sexually assaulted in March 2011 while walking home from a picket line, though police were never able to confirm that the attacks were related to the strike. Far-right counter-protesters and politicians harassed striking workers at several postal facilities, holding placards and chanting "Comere le prole!" ("Eat the unions"), though prominent far-right politician Marco Quirinamo later called the protests "unofficial". Grandinetti levelled sharp criticism at Quirinamo and his supporters, calling the demonstrations "Nazi-esque".

Other picketing workers had beer, sugary drinks, hot liquids, mud, and feces thrown at them by people passing by in vehicles. A trio of 17-year-old males were apprehended after one such attack and subsequently charged. The attacks were condemned by both union leaders and the government.

Prime Minister Brunate lambasted the teens in a fiery speech the day after their arrest. He said that the attacks were not "in the spirit of what it means to be Pacitalian", and that "Pacitalian people were disgusted by what they witnessed [...] a gross violation of our collective freedom of expression and assembly". He called for an end to "disrespect" and "intimidation" and "inappropriately expressed frustration".

Union leaders said they appreciated the prime minister's comments, but questioned whether the comments were genuine or simply a reflection of Brunate's governing coalition falling further and further behind in public opinion polls. Nevertheless, they demanded the government do more to protect striking workers.

The government's inability to make progress, and growing frustration among voters at the lack of resolution, were seen as major factors for the centre-left Brunate coalition's defeat in parliamentary elections in November 2011. The then-opposition FPD had promised to end the strike as soon as possible with back-to-work legislation, but also guaranteed reasonable wage hikes and changes to Corriere's operations as a compromise.

Resolution

The Nera government tabled back-to-work legislation in February 2012 after a final attempt at mediation in January failed to achieve any resolution. Citing overwhelming public opinion in favour of an imposed contract, and the attempt to fulfill a campaign promise, the prime minister said "at the same time, the government [had] no interest in being a bully". Instead, Nera argued the government's contract for postal workers would "end the postal workers' dispute in a fair, equitable manner for all Corriere workers, for the Pacitalian public and for the government [...] all those affected by this shutdown".

The move enraged the SCPM and other labour unions. The union representing workers at the Pacitalian state-owned railway, SFR, unexpectedly walked off the job in the middle of the day as part of a sympathy strike, a few days after the legislation was introduced. The walkout was in protest of the imposed contract, with railway workers decrying a violation of the collective bargaining process. The job action only lasted a single day; nevertheless, millions of commuters and travellers across the country were stranded due to the unanticipated action.

By 2012, there was a clear difference of opinion among the public on whether the SCPM's action was a "strike", which implied negative connotations towards the workers, or a "voluntary lockout", as some left-leaning pundits argued, implying the government had essentially forced the strike in the first place back in 2010, by allowing the old collective agreement to lapse. The prime minister, however, appeared careful to choose neutral language when discussing the back-to-work legislation.

Terms of the new contract

The new contract, which was intended to take effect immediately upon the ratification of the bill by the Archonate, contained several compromises by the government, in an attempt to get Corriere employees back to work as soon as possible. For example, the government dropped its attempt to reduce pay, as well as its further demand to scale back benefits and pension payments for both new and existing employees. It also attempted to craft a solution that did not mandate the privatization of any parts (or the whole) of the company.

The imposed contract was valid until December 31, 2029. Nera hailed the bill as a way to "stop the bleeding" at Corriere and maintain as much of the company as possible while transforming it from an unprofitable enterprise into a profitable one. Independent auditors estimated the new contract and the reorganization efforts would save Corriere upwards of Ð 850 million a year.

The legislation was heavily criticized by labour leaders, and the opposition, for its drastic cuts to the company's workforce, which totalled nearly 20 percent across all departments. The bill also moved to transition some full-time employees to "seasonal and/or conditional employment", and minimized scheduled pay raises over the next few years.

- Reduction in the workforce

- The government would eliminate 18,434 full- and part-time positions by the end of 2012, a total reduction of almost 20 percent.

- 6,550 positions would be cut from retail and other "customer-facing" operations; 4,353 positions cut from mail delivery; 3,201 positions cut from general operations; 1,639 positions cut from courier and corporate services; 1,112 positions cut from call centres; 892 positions cut from sorting; 339 positions cut from shipping; 193 positions cut from administration; and 155 positions cut from human resources.

- The government would eliminate 18,434 full- and part-time positions by the end of 2012, a total reduction of almost 20 percent.

- Seasonal workforce adjustment program

- The government would mandate Corriere to permanently transition up to 2,800 full- or part-time employees to seasonal and/or conditional employment based on business needs, such as for holiday, on-call, or other work.

- Pay increases

- The government would offer a fixed, uniform annual raise to all employees, broken down as follows: 2.5 percent retroactive to the start of the strike; 1.25 percent for 2012; 2.025 percent for 2013; and 2.875 percent plus cost-of-living adjustment every year starting in 2014, until the expiration of the new contract.

- Hiring freeze

- Remained in effect until January 15, 2013. After this time, Corriere was permitted to resume recruitment, but had to give priority to re-hiring laid-off employees.

- Retail consolidation program

- Post office outlets that were losing money were to be closed by December 31, 2014.

- Headcount at smaller post offices would be reduced to a maximum of eight full- and part-time total.

- Financial services

- Government committed to completing the reintroduction of postal banking, which had ended in 1994.

- Corriere would shift existing international wire transfer, bill payment, and currency exchange services into the new Postbank, instead of offering these at the mail counter.

- Benefits, pension and tenure

- No changes.

- Mail delivery

- Permanent reductions in regular delivery, elimination of Monday and Saturday general post service.

- No changes to courier and shipping services.

- Sorting and logistical operations would continue on Mondays.

- No privatization clause

- Commitment not to privatize or shutter any services or departments until at least January 1, 2016.

Postal Service Dispute Resolution Act

The bill to legislate postal workers back to work and restructure Corriere Nazionale was titled the Postal Service Dispute Resolution Act, 2012 (RNA code 12 S01). It passed the Constazione, 604–0, on March 6, 2012, with the government coalition voting unanimously in favour.

The two main opposition parties, the Greens and the DNP, used all of their allocated time to speak against the legislation in an attempt to stall it, and walked out in protest when the bill was put up for a vote. They were joined by the two members of Libertad Marquería Juntos. The Christian Democrats, though not in the governing coalition, supported the legislation.

Political pundits chastised the opposition for walking out during the vote, and for opposing the legislation, with several right-leaning television personalities defending the government's actions, and blaming the Greens, DNP and PSC for failing to resolve the postal strike while they were in power.

The bill was then sent to the Senato, the upper house of the Pacitalian parliament, and passed in the same manner, with the governing coalition supporting it unanimously. Notably, the bill had no formal votes to oppose it, but this was because opposition senators walked out of the chamber before the vote. After the final vote on April 16, 2012, in the Senato, affirming the legislation, the bill was sent to the desk of Archonate Franchessa Marconi for republican assent.

Though several union leaders, opposition politicians, and leading left-wing pundits publicly urged Marconi to veto the legislation, she replied that, as the head of state, she was "constitutionally obliged" to act "in the interest of the country" and "at the discretion of the elected parliament", and, therefore, would sign the bill into law. She did so the following week, with a decree that the law would enter into force on May 14, 2012.

Aftermath and legacy

Corriere Nazionale resumed partial operations on the date of the new law's entry into force, and released a public statement outlining their goal to resume normal operations by July 1, 2012. The corporation apologized for the lengthy suspension of its operations, and expressed its regret over how the job action had caused the complete suspension of all mail delivery.

Packages, post and other shipments sat undelivered in Corriere warehouses for two years and several viral posts on social media throughout 2012 and 2013 depicted parcels finally reaching their intended destinations two years late. Several media outlets and pundits had derisively labelled this odd consequence of the strike action a "postal purgatory". In some cases, Corriere returned mail and parcels to their addresses of origin, rather than delivering them, causing the postal service further embarrassment, and generating more frustration and anger among customers.

Chief executive officer Cornelio Fratelli submitted his resignation to the Pacitalian government effective May 21, 2012.

The change in government in the previous year's elections had resulted in organizational changes in the Pacitalian government, including the abolition of the "Energy, Natural Resources and Public Utilities" super-portfolio that had been held by Tomás de la Marques. Rosa Puig i Damès, the new interior minister in the Nera government, was now the cabinet member directly responsible for public utilities. Puig i Damès appointed Bernardo Bernardino the new CEO and dismissed the corporation's board of directors.

Meanwhile, the minister's office released a statement regarding the timeline of the corporate restructuring outlined in the back-to-work law. The government had completed almost all of the proposed restructuring by the end of 2013, and, in 2015, Corriere turned its first profit in 25 years. The company's headcount returned to its pre-strike total by 2021.

Arguably, the most significant legacy of the strike was the creation of Postbank, which reintroduced postal banking in Pacitalia after a nearly two-decade hiatus. The previous postal banking service, Banco Postale, had been shuttered in 1994 by the Santo Ragazzo government, and its assets had been acquired by Banco di Mandragora. The new Postbank was immediately successful, offering an alternative banking option to traditional large Pacitalian financial institutions. As of 2023, it is the sixth-largest bank in Pacitalia by total assets.

The Fiscal Audit Office, an arms'-length government agency that oversees government budgets and fiscal policy, has estimated that reorganization efforts, combined with revenue from the reintroduction of postal banking, have saved or generated Corriere a total of approximately Ð 14 billion ($38.5 billion) since 2012.