Protohistory of Themiclesia: Difference between revisions

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The '''Protohistory of Themiclesia''' (先史, ''ser-s.rje′'') refers to the instances where non-Themiclesian authors refer to Themiclesia, chiefly prior to the advent of written history in Themiclesia. The term '''Protohistoric Period''' (大古, ''ladh-ka′'') is also the name of a period in Themiclesian history, prior to the [[Themiclesian Dark Ages|Dark Ages]]. The dating of the Protohistoric Period depends on the dates of the materials that reference it; conventionally, the dates from 2000 to 800 BCE are used. The study of Themiclesian protohistory is often concerned with identifying references with cultures or geographic sites in Themiclesia, a task that often is controversial. | The '''Protohistory of Themiclesia''' (先史, ''ser-s.rje′'') refers to the instances where non-Themiclesian authors refer to Themiclesia, chiefly prior to the advent of written history in Themiclesia. The term '''Protohistoric Period''' (大古, ''ladh-ka′'') is also the name of a period in Themiclesian history, prior to the [[Themiclesian Dark Ages|Dark Ages]]. The dating of the Protohistoric Period depends on the dates of the materials that reference it; conventionally, the dates from 2000 to 800 BCE are used. The study of Themiclesian protohistory is often concerned with identifying references with cultures or geographic sites in Themiclesia, a task that often is controversial. | ||

== | ==Scholarship== | ||

The modern study of the protohistory of Themiclesia is usually attributed to the monograph ''Studies on Themiclesian Antiquity'' published by Benedict S. Kun in 1798. Pursuing the importance of lapis lazuli and turquoise in the early history of Themiclesia, Kun began collecting what he believed to be references to Themiclesia in other historical traditions, feeling that the thitherto-unquestioned notion that Themiclesia was founded by Menghean settlers to be unsatisfactory when lapis lazuli was a widely used material in the ancient world. While many of his conclusions proved spurious, references to Themiclesian gems in ancient Maverican poetry was subsequently confirmed by other scholars. The confirmation of Maverican references to prehistoric Themiclesia was seen as a watershed moment for Themiclesian historiography, which had exclusively relied on Menghean literature to describe Themiclesia prior to the advent of written history. | The modern study of the protohistory of Themiclesia is usually attributed to the monograph ''Studies on Themiclesian Antiquity'' published by Benedict S. Kun in 1798. Pursuing the importance of lapis lazuli and turquoise in the early history of Themiclesia, Kun began collecting what he believed to be references to Themiclesia in other historical traditions, feeling that the thitherto-unquestioned notion that Themiclesia was founded by Menghean settlers to be unsatisfactory when lapis lazuli was a widely used material in the ancient world. While many of his conclusions proved spurious, references to Themiclesian gems in ancient Maverican poetry was subsequently confirmed by other scholars. The confirmation of Maverican references to prehistoric Themiclesia was seen as a watershed moment for Themiclesian historiography, which had exclusively relied on Menghean literature to describe Themiclesia prior to the advent of written history. | ||

Revision as of 09:18, 3 March 2021

The Protohistory of Themiclesia (先史, ser-s.rje′) refers to the instances where non-Themiclesian authors refer to Themiclesia, chiefly prior to the advent of written history in Themiclesia. The term Protohistoric Period (大古, ladh-ka′) is also the name of a period in Themiclesian history, prior to the Dark Ages. The dating of the Protohistoric Period depends on the dates of the materials that reference it; conventionally, the dates from 2000 to 800 BCE are used. The study of Themiclesian protohistory is often concerned with identifying references with cultures or geographic sites in Themiclesia, a task that often is controversial.

Scholarship

The modern study of the protohistory of Themiclesia is usually attributed to the monograph Studies on Themiclesian Antiquity published by Benedict S. Kun in 1798. Pursuing the importance of lapis lazuli and turquoise in the early history of Themiclesia, Kun began collecting what he believed to be references to Themiclesia in other historical traditions, feeling that the thitherto-unquestioned notion that Themiclesia was founded by Menghean settlers to be unsatisfactory when lapis lazuli was a widely used material in the ancient world. While many of his conclusions proved spurious, references to Themiclesian gems in ancient Maverican poetry was subsequently confirmed by other scholars. The confirmation of Maverican references to prehistoric Themiclesia was seen as a watershed moment for Themiclesian historiography, which had exclusively relied on Menghean literature to describe Themiclesia prior to the advent of written history.

After the decipherment of the Achahan script in the 20th century, scholars discovered more early references to Themiclesia, but some of these remained contentious. One tablet used the phrase "place where the sky meets the earth and forms sky-blue stones" to describe the source of lapis lazuli ore; one scholar in the field identifies this with Themiclesia due to its perceived distance and mineral output, but others believe it merely refers to a distant place and cannot definitively point to Themiclesia. Other tablets refer to Themiclesia with more certainty, often with the descriptor of "the western end of dry land".

History

While there are confirmed references to Themiclesia spanning 2000 to 800 BCE, there is no historical work in sensu stricto. Scholars have attempted to combine references in external texts with archaeological findings to reconstruct pre-Meng Themiclesia, with varying degrees of success.

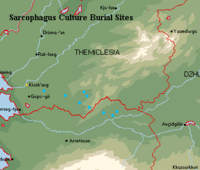

There are a number of prehistoric societies in Themiclesia that have very probably interacted with Proto-Chikai or Achahan states. The Sarcophagus Culture, noted for its pastoral lifestyle and large, stationary communal sarcoaphagi, is a plausible candidate for the early circulation of lapis lazuli and turquoise from Themiclesia. It was not associated with the extraction of minerals, likely exchanging it for wool with other cultures towards northwestern Themiclesia. Unpolished lapis lazuli was used as funerary ornaments and typically placed in the hand of the deceased. The Sarcophagus Culture did not developed permanent settlements or central authority that could influence the trade of gemstones, but they were probably traded through mutual contact between pastoral groups in transhumance and longer patterns of migration. Their movement permitted the minerals to travel into northern Maverica, where further contact with Chikai or Achahan merchants was possible. As the earliest Sarcophagus Culture burials with lapis lazuli date to the middle of the 3rd millennium, such a scenario predates the opening of the Lapis Road in the 12th century. The preferred pastures of the Sarcophagus Culture seemed to move south and west as time progressed.

Lapis lazuli became a preferred gemstone in the later phase of the Proto-Chikai culture as suggested by recovered artifacts. Modern mineral composition analyses suggest that some of these stones originate as far as western Themiclesia. However, the regions of activity of the Proto-Chikai state and the Sarcophagus Culture do not intersect, suggesting that other intermediaries were present. If so, the Crown Culture has been identified as a possible candidate, as it also obtained lapis lazuli from western Themiclesia and used it in ritualistic contexts, as well as larger quantities. The Crown Culture vanished circa 1900 BCE.

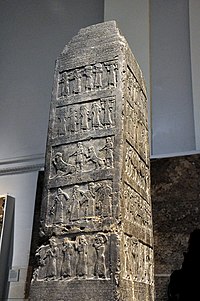

The expansion of Achahan Empire under King Adaran in the 13th century led to permanent Achahan presence in northern Maverica. This in turn permitted merchants to establish regular contact with nomadic groups in the area and trace the origins of lapis lazuli, ultimately creating the Lapis Road recorded in Achahan literature as an accomplishment in tribute to King Adaran. In Sarcophagus Culture burial sites, an increase in bronze grave goods is seen to be reflective of increased frequency of trade. The name of the nomadic group from which Achahan merchants obtained lapis lazuli is usually called N-Q-R, whose pronunciation is uncertain; however, it appears from contextual clues that trade with this entity is seasonal, and the entity is regarded to appear in the west of the empire. While the identification of N-Q-R with the Sarcophagus Culture is ultimately uncertain because it has left no trace of its language, pictorial evidence of a man wearing an tunic fastened with a knotty chain thought to be distinctive of the culture is depicted on the Black Obelisk of King Adaran with the caption:

I have received 1,000 sky-blue stones and 1,000 sea-blue stones from N-Q-R (?), a herder from the Far West.

And again on a wall inscription in the front gate to the city of Achahan and in its throne hall, dated around 1200 BCE, recounting the king's depredations:

And N-Q-R, a herder from the Far West, whom my grandfather has subdued and my father has subdued, bowed down to my foot, giving me 5,000 sky-blue stones and 5,000 deep-blue stones, and putting his men, women, flock, and goods upon my kingship and my power. He said, "Thou art king of Achahan, king of the desert, king of the pastures, king of all the cities, king of kings." My grandfather's dominion, I have preserved and magnified.

I have placed the gold of P-N-S and the blueness of N-Q-R upon my grandfather's throne and my father's crown. My kingship and my greatness extends [...] lands human eyes have seen and feet have walked.

After 1200, Achahan merchants frequently traversed northern Maverica, possibly with the guidance of nomads from the Sarcophagus Culture, and reached as far west as the Themiclesian Bay; however, it appears that most trading activity was mediated by the Sarcophagus Culture until the decline of the Achahan civilization. During this roughly 200-year span, Achahan artifacts are frequently found in sites associated with the culture. Many are personal seals peeled off, probably used by merchants for authentication, suggesting that some herders interacting with Achahan merchants had some level of literacy. In the 10th century, changing climate and political hostility have been cited as reasons that compelled the Sarcophagus Culture to retreat from the Central Hemithean basin westwards. Its easterly burial sites were no longer actively used after about 950. At the very end of the Sarcophagus Culture, it appears a minuscule amount of cuneiform tablets were buried with its dead. Since these tablets do not appear to be Proto-Chikai or Achahadian, some scholars think it may be surviving examples of the culture's language; however, decipherment has been thoroughly prevented the extremely limited and fractured corpus, amounting to no more than 30 examples and some 41 recognizable symbols. The familiar N-Q-R sequence associated with the culture does not appear this corpus.

Sources

Maverica

In the Old Maverican poety of the Ṛgveda, particularly in poems 2.21, 2.24, 5.10, and 7.9, lapis lazuli are described as having been brought from "across the sea". This sea is identified with the Inland Sea that now forms part of the border between Maverica and Themiclesia today.

Proto-Chikai and Achahan cultures

The Proto-Chikai cuneiform tablet CK3101, reading "on account of the sky-blue stones and sea-blue stones from the occidental land across the desert", is usually intepreted to be a reference to the area that is now Themiclesia and its richly-exploited mineral deposits of lapis lazuli and turquoise. After