Passenger rail transport in Themiclesia: Difference between revisions

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

In 1885, the first limited service (特快, literally "singularly express") appeared, the term "limited" indicating a schedule that brooked no yields or delays for any other train whatsoever. The limited service was alloted the highest priority on the line, and the engine and entire rolling stock were customized to maximize speed and minimize water and coal stops. Given that a limited service must have a restricted number of stops, they were similarly amenable to seat reservations, and indeed in practice seats on limited services were always sold as reserved seats. Advertisements appealed to a strong sense of prestige in travelling with a reserved seat, on a service that ranked above other trains on the same route, and with the best engines and rolling stock available. It was the general practice of the 1880s through 1900s that limited trains consisted of only first and second class coaches—third class coaches were not used on limited services. | In 1885, the first limited service (特快, literally "singularly express") appeared, the term "limited" indicating a schedule that brooked no yields or delays for any other train whatsoever. The limited service was alloted the highest priority on the line, and the engine and entire rolling stock were customized to maximize speed and minimize water and coal stops. Given that a limited service must have a restricted number of stops, they were similarly amenable to seat reservations, and indeed in practice seats on limited services were always sold as reserved seats. Advertisements appealed to a strong sense of prestige in travelling with a reserved seat, on a service that ranked above other trains on the same route, and with the best engines and rolling stock available. It was the general practice of the 1880s through 1900s that limited trains consisted of only first and second class coaches—third class coaches were not used on limited services. | ||

===Pre- | ===Pre-war regulation era=== | ||

By 1890, revenue mileage of main and branch lines in Themiclesia reached 9,520 km. Railroad had been largely an unregulated business, as it was assumed that the demands for goods would guide them towards building efficient lines. On the freight side, the laying down of parallel railways and price cutting competition cut railway profits to razor-thin margins and occasioned the first bankruptcy in 1891, and the government began to regulate the building of railways, though leaving passenger services on them, which had higher margins (though not necessarily more profits ''in toto'') than freight, mostly untouched. | By 1890, revenue mileage of main and branch lines in Themiclesia reached 9,520 km. Railroad had been largely an unregulated business, as it was assumed that the demands for goods would guide them towards building efficient lines. On the freight side, the laying down of parallel railways and price cutting competition cut railway profits to razor-thin margins and occasioned the first bankruptcy in 1891, and the government began to regulate the building of railways, though leaving passenger services on them, which had higher margins (though not necessarily more profits ''in toto'') than freight, mostly untouched. | ||

The process of consolidation eventually brought a standardized set of passenger service rules to most routes, or at least the main lines. In 1895, it is generally the case that on each line there can only be one limited service (the LR train) running at any given time, to satisfy the "top priority" component of the LR service. On popular routes, there could be multiple reserved expresses, but usually only one was the LR of the route; if there were two, either they were day and night services (the "sleeper limited" or "SL") respectively or one was a temporary/charter service. After 1900, railways sometimes ran two or more limited services that had no possible scheduling conflicts and gave them separate names (the "Coastal Reserved" and "Star Reserved" under numbers 3/4 and 15/16 are examples of two limited services on the same route). On timetables, these names trains were noted as "the ''name'' reserved", e.g. the Coastal Reserved (海對號). | The process of consolidation eventually brought a standardized set of passenger service rules to most routes, or at least the main lines. In 1895, it is generally the case that on each line there can only be one limited service (the LR train) running at any given time, to satisfy the "top priority" component of the LR service. On popular routes, there could be multiple reserved expresses, but usually only one was the LR of the route; if there were two, either they were day and night services (the "sleeper limited" or "SL") respectively or one was a temporary/charter service. After 1900, railways sometimes ran two or more limited services that had no possible scheduling conflicts and gave them separate names (the "Coastal Reserved" and "Star Reserved" under numbers 3/4 and 15/16 are examples of two limited services on the same route). On timetables, these names trains were noted as "the ''name'' reserved", e.g. the Coastal Reserved (海對號). | ||

By the 1920s, limited services were no longer as uncommon as they once were, and in 1930 alone there are over 15 LR services, generally with a 4-6-4 engine pulling six I/II coaches. Calls for the inclusion of III class on LR trains reached parliament, prompting a directive to study the feasibility. However, lower profit margins and the large quantity of expected III passengers, which would make seat reservations very taxing, left operators hesitent to operate III on LR trains. It was feared, at least in National, that including III coaches on LR services would alienate those paying for a more exclusive mode of travel. Nevertheless, to respond to parliamentary views, National Rail operated from 1931 the very plainly named "Limited Express" ("LE") with only III coaches but using the same engines and similar schedules; reserved seating was not provided, | By the 1920s, limited services were no longer as uncommon as they once were, and in 1930 alone there are over 15 LR services, generally with a 4-6-4 engine pulling six I/II coaches. Calls for the inclusion of III class on LR trains reached parliament, prompting a directive to study the feasibility. However, lower profit margins and the large quantity of expected III passengers, which would make seat reservations very taxing, left operators hesitent to operate III on LR trains. It was feared, at least in National, that including III coaches on LR services would alienate those paying for a more exclusive mode of travel. Nevertheless, to respond to parliamentary views, National Rail operated from 1931 the very plainly named "Limited Express" ("LE") with only III coaches but using the same engines and similar schedules; reserved seating was not provided, making overcrowding likely. The service was a financial success, many willing to risk a standing journey that was at least shorter—compared to a standing journey on a stopping train that could run easily for twice as long. | ||

In 1935, Themiclesian Rail introduced mechanical {{wp|air conditioning}} on its premier service from Kien-k'ang to Twar. The air conditioning fee was initially tariffed at 15% of the pre-AC ticket value but was soon abandoned. However, such conversions were postponed on the National Rail owing to the oubreak of the war. | In 1935, Themiclesian Rail introduced mechanical {{wp|air conditioning}} on its premier service from Kien-k'ang to Twar. The air conditioning fee was initially tariffed at 15% of the pre-AC ticket value but was soon abandoned. However, such conversions were postponed on the National Rail owing to the oubreak of the war. | ||

Revision as of 00:10, 1 May 2024

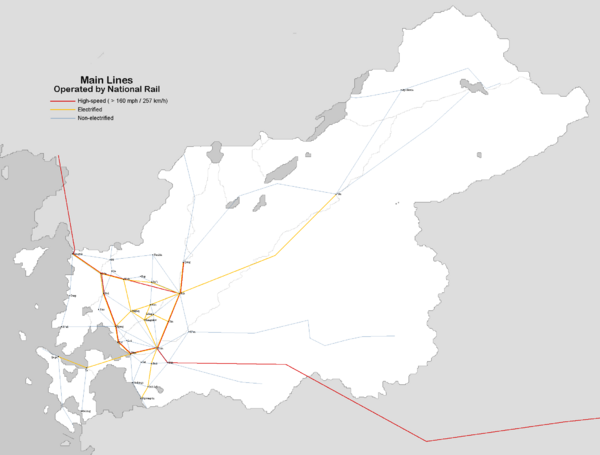

Rail transport in Themiclesia originated in 1829 for shipping coal and now encompasses a large network of railways serving both passengers and freight. Inter-city railways grew with government support from 1853 and accompanied the Industrial Revolution to support long-distance commerce and modernizing manufacturing needs; these inter-city railways were bought by the government between 1892 and 1898 to prevent the laying of redundant railways, but private companies continued to operate trains on nationalized railways and branch lines. Improved revenues were taxed by the government to support expansion and maintenance of infrastructure. Urban railways and trams appeared the late 19th century. More recently, branch lines have seen development, and a high speed rail with speeds up to 300 km/h was introduced in 1967.

Despite a decline in ridership in the 1960s, the railway continues to be a principal means of both urban, suburban, and inter-city travel in Themiclesia. Inter-city transport is mainly offered by National Railway, a joint venture of public and private investment, but excursion trains are regularly operated by private companies. The railway accounts for nearly half of all inter-city freight by weight, but less by value as it is better suited to bulk goods in loose or containerized format.

History

Mining railways

The first railway in Themiclesia was laid down in 1831 by Asikainen, a Hallian company oeprating a coal mine in Prets. The company had relied on draft animals and barges to ship its products into the Meh but found a more profitable mine away some 16 km from the river, which a railway covered. The line was operated with a single locomotive, the Kaveli. The introduction of the railway made Asikainen more profitable than others relying on draft animals, and by 1840 no fewer than eight mining operations utilized railways in the Themiclesian north, where mining rights have been leased to Hallia through the Treaty of Kien-k'ang of 1796.

In 1844, a railway from Prets to Gra was opened, which allowed Hallian merchants to undercut coal from Themiclesian mines, transported by draft animals. This coal was not tariffed as it was not technically imported, but it became a political crisis at the lobby of Themiclesian coal mines and merchants, who argued that the Hallian miners were outselling domestic miners. In 1844, the government responded by awarding land to Themiclesian mines that they might lay their own lines, and a testing railway was laid down between the market town of Ngek and Kien-k'ang in 1845, spanning 65 km.

1845 – 1870

A royal commission was issued at the same time to study the effects of railways on foreign states, with the conclusion that an efficient transport system allowed more goods to be marketed domestically and would be an incentive to investment in businesses. The government also saw value in a railway system as a component of defence logistics, as troops could be moved around the country more rapidly and without requisitioning goods from the towns they passed through. As a result of the initially-good results of test railway and of the recommendations of the royal commission, the building of railways became the Ra-lang government's policy. New railways were constructed with government grants in land and backed by high-interest bonds sold to the government. In 1847, the first inter-city railway over 300 km opened between Kien-k'ang and Twar, hoping to compete with river transport and to open a passenger service, bringing individuals arriving by boat to the capital city.

In 1854 and 1855, both Menghe and Dayashina agreed to elimiate trade barriers with foreign states, with the result that the trinity of Themiclesian exports—porcelains, tea, and silks—now faced stern competition. Themiclesian exporters became uncompetitive at Casaterran markets, triggering the Depression of 1857, which rippled to railway bonds as the first railways struggled to generate sufficient revenue to cover interest rates. Facing dwindling customs revenue, the Ra-lang government diverted its money to stimulate other industries and could not continue to support the building of railways. By 1861, Themiclesian industry regained its footing, and new railways were built to transport grain from docks to the cities that experienced population boom. Manufacturing businesses began to rely more on railways to source materials from the countryside. A second, largely privately-funded drive to build railways in the 1870s thus occurred.

The 1850 – 60s also saw the first regulations appear over travelling conditions and amenities. In 1853, it had been decreed that railways shall not carry passengers in "vehicles not made for the transport of mankind", to prohibit mining railways from carrying them in coal wagons or on carriage roofs, but the law was passed mostly on the strength of public outcry arising from a terrible accident in 1852. This requirement was made operative in 1857 by requiring each operator to inspect the structural soundness of its coaching stock annually. In 1865, third-class passengers obtained rights to seats, a roof above the compartment, and openings for lighting and ventilation, but this did not require glazing, a hole in the carriage wall being judged sufficient. In 1864, the Railways Act required railways to charge no more than 1 grain per Imperial mile travelled. Though facilitating urbanization, fare restrictions also discouraged railways from offering improved coaches in third class.

Revenues on early railways were chiefly generated from freight, so passenger trains were not initially prioritized; by 1859, travel by railway gained in popularity against private coach as the more comfortable and punctual option, and operators increasingly used passenger services to generate revenues, evidenced by booming variety in railway coach design and manufacture. In 1863, the first express passenger service appeared, connecting Kien-k'ang, Sin, Rak, and Qwang; the train took 16 hours to cover the 402 miles between the cities.

1871 – 1890

The only railways that received government funding between 1871 and 1892 were ones connecting mining towns in the northeast to the Themiclesian heartland, as distances were too long for private investment to cover; additionally, the government welcomed the establishment of homes and businesses in the distant countryside, as it was seen to ward away territorial claims by other powers. Under these auspices, the Great Northeastern Railway was completed in 1884, extending over 2,200 km to reach ′An from Rak. In these, the government took an interest in tariffing goods shipped but did not interfere with their operations.

In terms of railway operators, the operator and coachbuilder Lower Themiclesia Railroad (LTRR) achieved renown for its sleeper coaches that debuted in 1866, and these dominated the long-distance market owing to long running times on routes hastily laid and of poor geometry. LTRR also accrued considerable profit from exporting its exquisitely-appointed rolling stock, nicknamed "palace cars" on foreign railways; to accomplish this, it employed skilled artisans, some from manufacturers of porcelains and luxury fabrics. Though these exports were successful, it soon sparked competition, most notably in Tír Glas and adjoining states, and the domestic market remained its main source of revenue.

Between 1871 and 1890, much effort was made to accelerate passenger trains as operators realized that express fares were far more profitable than those stipulated for parliamentary trains. In consequence of this effort, passenger services began to diversify in terms of rolling stock, scheduling, and associated services like seat reservations. While sleeper services had boomed in the 1870s, day expresses started to challenge sleepers in the 1880s on some routes that formerly must be served by sleepers in premium services, owing to running times. The service from Kien-k'ang to Qwang, taking 16 hours in 1863, was shortened to 10:40 by 1880, making a daytime express service practical. Such changes were enabled by consistent improvements in lines, engines, and schedules.

In 1877, the first reserved service (對號), where all passengers were guaranteed a reserved and assigned seat, was operated. This was only practical on trains with limited calls, as the reservation process required maintenance of a seating record (one ledger representing the seating situation between each stops), to ensure a specific seat was always available. The practice of seat reservation was carried over from sleeper services (where each bed was sold only once per journey), but when applied to day trains, seat assignment was co-ordinated by telegraph between stations such that a single seat could be used more than once per journey; the process was labour intensive and sold for a hefty premium as an element of prestige.

In 1885, the first limited service (特快, literally "singularly express") appeared, the term "limited" indicating a schedule that brooked no yields or delays for any other train whatsoever. The limited service was alloted the highest priority on the line, and the engine and entire rolling stock were customized to maximize speed and minimize water and coal stops. Given that a limited service must have a restricted number of stops, they were similarly amenable to seat reservations, and indeed in practice seats on limited services were always sold as reserved seats. Advertisements appealed to a strong sense of prestige in travelling with a reserved seat, on a service that ranked above other trains on the same route, and with the best engines and rolling stock available. It was the general practice of the 1880s through 1900s that limited trains consisted of only first and second class coaches—third class coaches were not used on limited services.

Pre-war regulation era

By 1890, revenue mileage of main and branch lines in Themiclesia reached 9,520 km. Railroad had been largely an unregulated business, as it was assumed that the demands for goods would guide them towards building efficient lines. On the freight side, the laying down of parallel railways and price cutting competition cut railway profits to razor-thin margins and occasioned the first bankruptcy in 1891, and the government began to regulate the building of railways, though leaving passenger services on them, which had higher margins (though not necessarily more profits in toto) than freight, mostly untouched.

The process of consolidation eventually brought a standardized set of passenger service rules to most routes, or at least the main lines. In 1895, it is generally the case that on each line there can only be one limited service (the LR train) running at any given time, to satisfy the "top priority" component of the LR service. On popular routes, there could be multiple reserved expresses, but usually only one was the LR of the route; if there were two, either they were day and night services (the "sleeper limited" or "SL") respectively or one was a temporary/charter service. After 1900, railways sometimes ran two or more limited services that had no possible scheduling conflicts and gave them separate names (the "Coastal Reserved" and "Star Reserved" under numbers 3/4 and 15/16 are examples of two limited services on the same route). On timetables, these names trains were noted as "the name reserved", e.g. the Coastal Reserved (海對號).

By the 1920s, limited services were no longer as uncommon as they once were, and in 1930 alone there are over 15 LR services, generally with a 4-6-4 engine pulling six I/II coaches. Calls for the inclusion of III class on LR trains reached parliament, prompting a directive to study the feasibility. However, lower profit margins and the large quantity of expected III passengers, which would make seat reservations very taxing, left operators hesitent to operate III on LR trains. It was feared, at least in National, that including III coaches on LR services would alienate those paying for a more exclusive mode of travel. Nevertheless, to respond to parliamentary views, National Rail operated from 1931 the very plainly named "Limited Express" ("LE") with only III coaches but using the same engines and similar schedules; reserved seating was not provided, making overcrowding likely. The service was a financial success, many willing to risk a standing journey that was at least shorter—compared to a standing journey on a stopping train that could run easily for twice as long.

In 1935, Themiclesian Rail introduced mechanical air conditioning on its premier service from Kien-k'ang to Twar. The air conditioning fee was initially tariffed at 15% of the pre-AC ticket value but was soon abandoned. However, such conversions were postponed on the National Rail owing to the oubreak of the war.

Wartime

After the imposition of national mobilization to repulse the Menghean and Dayashinese invasion, inter-city railways were nationalized in 1937 to support the war effort. Themiclesian Railways and National & Maritime continued to be operators on the nationalized rail network, but government trains took priority, and rolling stock from both entities were regularly commandeered by the government. From 1936 to 1938, Menghean forces utilized forced labour, largely of prisoners-of-war of Casaterran descent, to construct a railway from Menghe to Themiclesia, through Dzhungestan, to ease a logistics bottleneck that had barred further deployment. Occasioning thousands of fatalities, the railway was called the "railway of death" by survivors of its construction. By the end of 1940, it is estimated that over 60% of intercity railways were under enemy control, though a number of key points such as sheds and bridges were demolished prior to their capture, and locomotives and rolling stock had been evacuated as much as practical.

During the war, the railway networks of both operators suffered considerable damage, some self-imposed. In 1947, the two railways merged to form the National & Maritime & Themiclesian & Northwest Railways but operated under the trade name of National Rail. This new corporation operated under Parliamentary charter and was required to re-invest a portion of profits into maintenance, employee welfare, and fare reductions before dividends could be paid to shareholders; to stimulate investment, the government reimbursed dividends paid to it as the major shareholder for the first 40 years of its operation. To compensate for damages to its infrastructure, the armed forces were ordered to transfer the industrial spurs it had constructed to National Rail.

Postwar

During the early phase of the post-war reconstruction period, the authorities minimized named trains and express services as they were liable to cause delays, in order to prioritize trains carrying key reconstruction materials; manual seat reservation, labour intensive, was likewise still suspended. Expresses reappeared. Between 1946 and 1948, named trains operated with II coaches only, as the railroad prioritized density in passenger services. But on 1 January 1949, the 1/2 Northern was restored to its pre-war I/II consist, and other reserved trains followed suit between 1949 – 50. Objections were heard against this development at a time when rationing was not yet lifted on food and other critical resources and amidst reports that I coaches were mostly used by ministers and officials.

Starting in 1947, National Rail introduced the Recliner coach, originally intended as an austere alternative to a sleeper on overnight services, as part of its day train services. These appear to have been intended to relieve the debarment of I coaches on named trains, in view of some of the ageing II stock. Recliners becoming well-received, the railroad extended them to other express services for a 10% surcharge. The recliner coach, with its airline-style layout and reclinable seats, was to have an extensive impact and gradually replaced older bay-style seating with non-reclinable and opposing seats on intercity services.

1950s to electrification

In the initial years of the 1950s, National Rail hosted several "general conferences" where a general plan for the railway's foreseeable future was laid out. Steam adhesion on all lines would be gradually replaced over 20 years with a mixture of diesel and electric adhesion, with electrification for six mainlines earmarked for passenger service. Dieselization would be marked by considerable and rapid savings over steam in operating costs, while electrical adhesion was seen as the more expensive option in the initial stage. Thus, the railroad eventually adopted a hybrid solution that would promote dieselization in the immediate term and transition to electrical power in the longer term and for select lines.

In 1954, the mainline electrification plan was further boosted with a planned "high speed express line" between the cities of Qwang-Rak-Kien-k'ang-Kwang, because the existing rail alignment had too many curves and was not direct. The high speed line was intended to make rail travel competitive with air. This line became the first operation line of the Themiclesian High Speed Rail in 1967. On this project, Themiclesian heavily co-operated with Dayashina in developing the track work and rolling stock that could yield revolutionary speeds.

Additional tractive effort afforded by diesel engines, the public railroad lengthened its express trains from six to ten coaches in the early 50s. Yet the named trains, which had the tightest schedules remained under steam adhesion until 1961, especially by the 4-6-2 Class 3700 and the post-war 4-6-4 Class 3900, which could reliably achieve a timetable speed of 107 MPH and outran any contemporary locomotive, steam or diesel.

In the passenger service department, National Rail was weary of the challenge of highways to rail, as seen in the flourishing state of national motorways in Hallia. The Themiclesian railroad publicly stressed convenience, punctuality, speed, and comfort as natural strengths of rail travel. In 1950, Themiclesia's intercity highway network was yet anemic, and the principal challenge posed by car ownership was instead in commuting, since the railways could not capture rapid suburanization promoted post-war as a matter of policy. National Rail declared a new policy in 1953 to improve railways, above merely restoring the railway to its pre-war state: all long distance travel should be by express train and with reserved seats, whereas in 1953 some 80% of Themiclesian still travelled by unreserved stopping train even long-distance.

Pre-war, National Rail operated "Express III" coaches with maximized density, catering to long-distance travellers willing to spend more for speed but not for comfort. After dieselization, the railroad lengthened III Limited Express consists from 7 to 12 coaches by the mid-50s. Starting in 1954, National Rail reduced seating density for the Limited Express services by substituting express for conventional III stock, which sat 120 passengers at 84' length (as opposed to 140 on Express III stock), recuperating the lost capacity with longer consists (which new diesel locomotives could pull). But rather than automatically offering the more spacious seats, the railroad called the more spacious coaches "New Third" and imposed a 20% surcharge. Since the "New Third" was effectivelly only a relabelling, an ensuing public outcry drove the surcharge down to 10%.

Computerized ticketing appeared in 1956, powered by the DPRM 1300 vacuum tube computer. With ledgers between stops now checked digitally, efficient reservation of seats for more or even all passengers was now possible. Indeed, the railroad planned that all intercity travellers should travel with reserved seats and on express trains. Long-distance travel on unreserved, stopping trains was expected to appear uncompetitive with road travel. Hence, the formerly unreserved Limited Express (特快) services all became reserved from December 1, 1957, the category renamed Reserved Limited Express (對號特快).

Highway B2 was planned for completion in 1957, and in view of challenges posed by road voyage on foreign railways, National Rail sought to remain competitive by improved comfort and introduced air conditioning, hitherto a I prerogative, on II coaches. The plan proved successful as the first private long-distance bus operator, Highway Bus Line, declared bankruptcy in 1960 amidst a tortured attempt to retrofit its fleet of wartime buses with AC units which turned out very prone to malfunction and leaks due to bumpy riding. The new II coaches with AC were powered by Head End Power generators behind the locomotive.

The 1950s was a transformative decade for National Rail's passenger service. At the end of the decade, the railroad offered a plethora of seating classes—First, Recliner, AC Second, Second, New Third, and Third. Railway commentators have mentioned the 1950s as one of the most successful decades of the railway's history, marked by a strong effort to take advantage of the booming economy and remain competitive against road voyage. A strong fiscal foundation has been attributed to the managmenet of the 1950s that ultimately made heavier infrastructure investments possible in the two following decades.

Post-electrification

Aside from the high-speed line, six other mainlines were also electrified for conventional speeds in the 60s and 70s. Initially, these lines saw electric locomotives hauling unpowered coaches much as diesel and steam engines had done before, but experience on the high-speed line also brought the electric multiple-unit trainsets or EMUs to conventional lines. Since the Inland Mainline's express passenger traffic was partly taken over by the high-speed line, the railroad rescheduled many services to make more stops, meaning the train needed to stop and then start more often. EMUs usually had acceleration performance superior to loco-hauled trains, so they would replace many loco-hauled trains on electrified lines.

Train classifications

Passenger services are classified by National Rail and T&S into the following categories, which determine the priorities trains have in allocation of right of way, particularly on single-track sections of routes or platform at stations. It should be noted that while schedulers respect train priorities, priorities are ultimately only guiding principles in drawing up the schedule and foresee and unforeseen operational issues can and regularly prompt the signal staff to grant right of way to a train of lower priority over one of higher priority.

| Service | Consist | Scope | Stops | Assigned seat | Train # | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reserved | 對號車, tups-qu-kla | First/Business or First/Business/Standard | Main lines only | No more than 10 stops | Always | 1 – 40 | Highest possible priority for a regular service, usually only one service per route and given a specific name. May be oriented towards tourists. |

| Night Express | 夜快車, laqs-kots-kla | Sleepers | Always | For long distance routes only | |||

| Reserved Limited | 對號特快車, tups-qu-neleq-kots-kla | Business/Standard or Standard | Yes | 41 – 300 | Main option for travellers between major cities | ||

| Intercity Express | 快車, kots-kla | No more than 1/4 of stops | Some | 301 – 800 | Main option for travellers between smaller cities | ||

| Regional Express | 縣快車, ghwin-kots-kla | Main and branch lines | Some | 1001 – 2000 | Generally running between two major cities on main and branch lines, serving short-distance travellers or as shuttle service to change trains at a major station | ||

| Local Train | 通車, qlwang-kla | Standard | All stations en route | No | 2001 – 3000 | ||

| EMU Limited | 電特快, nelinh-nelek-kots | Business/Standard | High speed lines only | All stations en route | Yes | 3001 – 4000 | Designation for all services on high-speed lines |

Reserved Train

Reserved Trains, usually only one or two services per route and are meant to represent the best service on that route. With few exceptions, Reserved Trains include dining facilities and premium coaches in first and business class. After the 1970s, these trains are often advertised to tourists or select business travellers and may have customized rolling stock to enhance their appeal. Fares are also the highest of all services, trumping high-speed lines; this is because Reserved Trains are subject to the Seat Reservation Surcharge and Limited Surcharge, which nearly double the ticket cost.

During the pioneering days of Themiclesian railways from 1845 to 1870, slow running speeds effectively required sleeper service to reach distant destinations in comfort, but considerable gains in speed in the 1870s and 80s allowed some journeys to be covered by a daytime service, albeit requiring a combination of prioritized schedules, advanced engines, and short consists to restrict tonnage. These were advertised as "limited" services by then-private railways, in contradistinction to "sleeper express" services that took longer; in the era of public regulation, the term "limited" still applied generally to the best possible service on a given route, and most were eventually nicknamed, e.g. Coastal Reserved (longest-running service, since 1894). Given the elite status of these services, they were always combined with seat reservation service and the best-appointed coaches; third-class coaches were not used on these trains.

Limited Express

Limited trains (formal name Reserved Limited Express) services are intercity trains providing fast and frequent service, calling at only major cities. As indicated by this stop pattern, these services are aimed at travellers who intend to travel quickly between cities and beyond a normal commuting/regional distance.

Despite the similar name, Reserved Limited services has a different and more recent origin compared to Reserved trains. Since the introduction of Limited Express (as a level of service above Express) in 1885 and until 1930, railways generally operated Limited Expresses only I/II coaches, not III, even though the vast majority of passengers (circa 95% in 1928) travelled III. In 1928, National Rail experimented with a III Limited Express service; to recuperate costs, National Rail used capacity-maximized stock, eliminated the dining carriage, and then oversold tickets to increase ridership even further. Seat reservation, a service standard to Reserved trains, was not offered, as manual reservation of seats ate into thin margins. Despite cramped accommodations and the lack of an assigned seat, the III Limited Express service was a commercial success, prompting its duplication in several routes. These services became increasingly popular through the 30s until the Pan-Septentrion War was joined in earnest.

After the PSW, Limited Express and Reserved services recommenced in 1947. In 1955, National Rail replaced some express steam engines with diesel engines, which enabled longer trains to run at express speeds, and the railway also gradually phased out the overly cramped pre-PSW coaches, the lost capacity being compensated by additional coaches. Two years later in 1957, National Rail computerized its seat reservation system and offered assigned seating to III Limited Express services. These improvements corroborate improving travel options for Themiclesians who could not formerly afford to travel in luxury―an intercity journey to visit friends and family by stopping train was quickly becoming unacceptable. In 1953, National Rail published a half-century report that asserted the future of railway was express trains for all intercity travel, and the category of Limited Express was slated for expansion to those goals.

Fare

Tariff

From the era of private railroading, Themiclesian railways had for the most part operated a three-class system adopted from Casaterran railways with one tariff for each class per mile travelled. Most roads had a 1:2:3 or 1:2:4 tariff ratio amongst III, II, and I class. Parliament mandated in 1901 the 1:2:4 tariff ratio for the public railroad. Until official repeal in 1977, this fare structure was mostly unmodified in the Public Railways Act, though the base tariff for III was modified from time to time, bringing along with it the tariffs for the other classes. Before the Pan-Septentrion War, a long-distance I class ticket could cost as much as 40 days' wages of a menial labourer.

Prior to the Pan-Septentrion War, each class of service was actively standardized through stable coach designs, so each tariff rate more or less corresponded to a single product. National Rail abandoned standarization as policy in order to introduce more types of coaches to remain competitive with road voyage and air travel. On the mainlines this was particularly apparent, while on the branches changes occurred at a more sedate pace. Newer coaches resulted in a plethora of products that sometimes made little sense to classify within a three-class system as hitherto done. The introduction of S6/2 III express coaches in 1967, which sat only 84 passengers on reclinable seats, made the S5 II reclinable coaches (seating 56) appear unreasonably expensive, being priced over double.

During and after the war, the government did not amend the laws to bring tariffs into line with inflation, prompting National Rail to rely increasingly on surcharges to increase revenues. By the 60s, it was rarely possible to purchase a ticket at base tariff; such services were often simply not available. Yet the fixed proportion amongst the classes' tariffs was often felt either to make III run at a loss or I to be altogether too expensive, or both at the same time. The great disparity in ticket prices obtained by the fixed proportions also somewhat conflicted with National Rail's plans to universalize reserved seating, air conditioning, and express speeds for all long-distance travel.

A more flexible fare system was argued for in Parliament in the late 60s and came to pass in 1975 when the three-class structure, as far as fare structure was concerned, was abandoned. Between 1975 and 1986, a general tariff ceiling was provided, leaving National Rail free to price other services as is competitive. After 1987, the law mandated that a basic service at a fixed tariff be provided at all stations, such that it should be possible to travel across the entire network at this fixed tariff at a reasonable level of service; as with other laws of this kind, National Rail resorted to running such baseline parliamentary trains to discourage patronage as much as possible.

| Date | III | II | I |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1901/2/1 | 1/24 | 1/12 | 1/6 |

| 1905/3/15 | 1/18 | 1/9 | 2/9 |

| 1917/3/1 | 1/10 | 1/5 | 2/5 |

| 1935/6/1 | 1/6 | 1/3 | 2/3 |

| 1958/1/1 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 |

| 1960/4/15 | 5/8 | 1 1/4 | 2 1/2 |

| 1962/12/1 | 3/4 | 1 1/2 | 3 |

| 1968/5/1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

Surcharges

The law left open the possibility to charge extra for additional services of value, which during the first decade of public management was mostly for reserved, express, and sleeper services. Yet to increase revenues from passengers willing to pay, National Rail introduced premium services that carried additional fees and also carved out certain services (formerly included in the ticket) to be subject to surcharges. For both I and II, the Catering Fee was assessed from 1922, nominally on services with onboard catering as opposed to meals brought in from stations, the idea being that freshly-prepared meals were more desirable.

A new Parlour Fee was charged on all I tickets from 1912, for use of the parlour section on D (for Drawing Room) carriages, but by 1927 all trains operating a I service included a D carriage, so the charge effectively became mandatory (even if the passenger never actually uses the Parlor section). Similarly, in 1935 air conditioning was introduced on I express stock, prompting a corresponding AC Fee on services with such air conditioned stock, yet by 1953 AC was retrofitted on all I stock, so the AC Fee became an inseparable part of the I tariff.

During the early stages of the PSW, National Rail introduced the Recliner Coach (RII) with an airline-style layout and seating 4 abreast in 13 rows (2x2 layout). These were originally a replacement for sleepers, which were felt to lack the austerity required by the war effort; as the conventional II coach (CII) sat 56 at 84' length, the capacity of 52 on Recliners was considered permissible. By 1947, National Rail started attaching the RII coaches on day trains. Originally tariffed the same as CII, National Rail imposed a 20% surcharge on the RII coaches, which then often co-existed with CII on the same train.

On the other hand, National Rail also eagerly expanded AC from I to II in the 50s, in an effort to stay ahead of road competition in comfort terms, since contemporary cars were not air conditioned. Due to the weight and size of AC units, these were roof-mounted in 1957 as part of the S5/2 (series 5, revision 2) streamlined coaches; AC units were not installed on RII coaches because this would make the coaches too heavy. To increase revenues and also betting that passengers would not mind losing some legroom for air conditioning, National Rail decreased the seat pitch to sit 64 passengers (as opposed to 56) at 84' length. These new AC coaches were priced between the RII and CII coaches.

Apparently, National Rail also resisted retrofitting AC units on Recliner coaches, believing if passengers wanted both reclining seats and AC, they would pay for I instead.

In the III department, the pre-war S4 express coaches sitting 140 and non-express coaches sitting 120 (both at 84') were quickly becoming unacceptably crowded, even though improving income levels rendered them more affordable than ever. Sensing shifting standards of comfort, National Rail simply repurposed non-express stock for express service and introduced a surcharge for the coaches with less density. The express stock was repurposed for suburban services, in which crowding was more acceptable due to short travel times. Much criticism was levied against these changes. Between 1954 and 1961, the two types of III carriages operated together.

Regulations

Railways in Themiclesia are subject to a number of legal constraints passed mainly to promote efficiency in rail transport and enhance safety. Many early regulations were made by Parliament, by whom most early routes were also authorized; however, the regulation of railways often became political, and varoius bodies such as the Board of Trade and later Ministry of Transport also became involved. Most modern regulations are made by ministers with statutory authorization, but basic regulations such as the track gauge for intercity railways are fixed by statute.

Units

The standard system of measurement on Themiclesian railways, for internal purposes, are Imperial units from Anglia, as much of the technology and rolling stock on the earliest non-Hallian railways were imported from Anglia. Railway lengths are signposted in terms of Imperial miles and chains. The descriptor "Imperial" (rendered phonetically as 音卑麗, rf ′im-pi-ryal) is added to the corresponding Themiclesian unit. However, to anticipate unexpected changes by Anglia, which have not yet happened, Imperial units in Themiclesian railways were retroactively fixed by a domestic statute to their definitions on Jan. 1, 1870. Some old lines, once under Hallian operation, had their sign-posts changed from Hallian units to Imperial ones by 1896. However, in support of the Government's desire to promote the Metric system, that system has been in use for public trade since 1957.

Track gauge

Broad gauge

Several lines in the north were built for a 5 ft (1,524 mm) gauge, especially those owned by Hallian companies. As it was unlawful to re-gauge any standard-gauge railway to a different gauge, the last 5-foot gauge main line was converted to standard gauge in 1894. Nevertheless, it was permissible to operate a different gauge

The Northern Riparian Railway, located in Ladh-mgon Province and on the border with Nukkumaa, runs on a 5 ft gauge that is unique to operational lines. It was built in 1846 and serviced two coal veins located on the Themiclesian side of the river. The line was acquired by Northwestern Railways in 1896, but due to dwindling freight and passenger service, it was never converted into standard gauge. It was abandoned in 1919 but restored for tourism in 1960. The line today services open-air dome cars offering views of the river.

Standard gauge

The modern standard gauge on Themiclesia railways is 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm), this gauge having been established in 1851 by the Rjai-ljang Government. Since that year, any railway measuring more than five miles between its most distant points was by law required to be built in this gauge, and all main lines currently operated by National Rail conform to it. Most branch lines and industrial spurs, which act as feeder lines for freight service on main lines, are also in this gauge.

Narrow gauge

There are several narrow gauges in Themiclesia, the majority built well after the 1851 law that established the standard gauge on lines longer than five miles. Narrow gauges were permitted on lines shorter than five miles and not connected to any standard-gauge line, but also longer railways not open for public business or for which public business represented a insignificant portion of its revenues. Likewise, they were permissible for tramways, which shared the road surfaces with non-rail vehicles. Narrow-gauge lines were often constructed in mines, farmland, factories, and private estates, where restrictive space or budget forbade the construction of wider railways.

In forests, where gradients tend to be steep and turns sharp, the 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) and 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) gauges were popular and accounted for the majority of forest railways. In the northeastern Kalami mountain range, there exists a 2 ft 6 in mountain railway. There are also a number of "tourist rails" that carry tourists from one attraction to another, built in the early 20th century, that are typically in narrow gauge; these lines utilize separate sheds and vehicles and are not joined to the intercity railway network, and some also regularly carry passengers. Some light rail and tramways are on a 3 ft 6 in gauge, including the system in Kien-k'ang and Tor.

Railways within coal mines and quarries typically operate under even more restrictive gauges, of which 2 ft (610 mm), 1 ft 11 1⁄2 in (597 mm), and 1 ft 8 in (508 mm) are attested in Themiclesia. These gauges are also not unknown to other applications in salt mining, agriculture, and gardens. Certain passenger railway operations, typically converted from industrial railway, also possess tracks in these gauges, though in recent years many of them have been regauged to more permissive dimensions.

Loading gauges

Old gauge

Prior to 1891, there was no standard loading gauge; the gauge on each private railway was decided by the narrowest point on its route. However, for goods wagons, it was commonly accepted that a normal width which would pass through most lines was 9 ft. The expansion of railways, however, encouraged proprietors to unify gauges across their entire network, so that a single wagon could run without the need to unload and reload. The old gauge was formalized only after the new gauge (below) became standard in the 1890s and was defined by a 9 ft (274 cm) and 12 ft 6 in (381 cm) envelope; while few lines were built to these restrictive dimensions, they were chosen for their universality applicability. Many branch lines may accommodate 9 ft 6 in or even 10 ft 2 in vehicles, though deficiencies in one dimension or another required rolling stock in the old gauge to be used in these lines. It is still seen on some branch lines currently, though periodic efforts have been made to upgrade them to the new gauge.

New gauge

When the Central Junction Railway was built, half of which was underground, dimensions of 10 ft 6 in (320 cm) wide by 14 ft 6 in (442 cm) tall were specified to accommodate the largest coaches then in use. This decision was meant to encourage railways to connect services through the Central Junction, which both provided the government a fee and reduced wagon traffic in Kien-k'ang, a major source of complaints. Between 1897 and 1910, most main lines owned by both National & Maritime and Themiclesian & Northwest were converted to the new gauge, while new constructions met the then-named Central Junction gauge. Because the continuous vaults of the underground sections are directly imprinted onto the limits of this gauge, it is also called the "tunnel gauge".

Though generous by 1890s standards, the 7-mile Central Junction tunnel under Kien-k'ang would by 1920 become the most restrictive point on the Inland Main Line, and widening or heightening the tunnel would entail rebuilding it and demolishing everything built above it. Railway engineers noticed that the immovable height limit could be circumvented if traffic were diverted through the suburbs, where trains ran above ground and were subject to fewer height restrictions. Such a practice led to the development of the over-tall gauge, which was seen on railways that passed through the sparsely-populated east.

New-new gauge

The new-new gauge is the electrified version of the new gauge and includes a modest 6-inch increase in vertical height, which enables double-decker trains to have better headroom. Restrictive height barriers were typically negotiated by lowering the track bed in the late 70s.

Over-tall gauge

The over-tall gauge originated in the 1920s after efforts were made to divert freight traffic from termini in major cities, as freight could travel more efficiently avoiding busy areas that are also more likely to have permanent structures that restrict gauge. Benefiting from benign geography, several lines were converted to accommodate boxcars as much as 16 ft 6 in (503 cm) by 11 ft 6 in (351 cm), whose heavier weight in turn encouraged larger and more powerful locomotives. Some of the largest locomotives ever in service in Themiclesia were built specifically for lines in this gauge. Some efforts were made to expand these railways for wartime requirements during the Pan-Septentrion War, which saw a further 6 in added to the width of the gauge. Despite this, the over-tall gauge is not widespread in Themiclesia, and some were (effectively) converted back to new gauge in the 70s by way of electrification.

Non-electrified lines in this gauge are mainly found in the Themiclesian east, where lines are generally single-track and have few factors which impose restrictions, like bridges and tunnels; on these lines, where services are less frequent, the ability to carry more goods per train was at a premium. After the 1970s, the excess height on the over-tall gauge permitted oversized rolling stock that catered to tourism that was booming in the east, formerly dominated by mining and forestry sectors.

Electric gauge

The electric gauge was developed jointly with Dayashina for high-speed passenger service. In the early 60s, Themiclesia proposed using its existing over-tall gauge to serve as the standard for a high-speed service, but Dayashinese engineers believed that those dimensions were too wide and not sufficiently tall to accommodate overhead catenaries that would be required to supply electricity. The modern electric gauge was thus settled to be 14 ft 9 in (4,500 mm) tall and 11 ft 2 in (3,400 mm) wide. This gauge is current on all high-speed electrified lines operated by National Rail under the brand name Themiclesian High Speed Rail.

Railway links to adjacent countries

Nukkumaa

Themiclesia is connected to Nukkumaa by at four operational railways, three of which are located in the western part of the country, and one in the far east. All four railways were built during the 19th century. One railway connected Themiclesia to Nukkumaa, Suurlaakso, and Uusimaa, where an ocean liner to Hallia was the principal means of communication between the Hemithean and Casaterran continents, and the three other railways principally served freight transport to various parts of the Hallian Commonwealth. However, there is a break of gauge at the Nukko border because the Hallian gauge, which is used in that country, does not conform to the standard gauge. Passengers typically transloaded onto Hallian rolling stock at the city of Skengrak, 9 km south of the border with Nukkumaa.

Dzhungestan

The first rail link between Themiclesia and Dzhungestan was constructed between 1937 and 1939 by Menghean forces to strengthen its logistics in the Themiclesian theatre during the Pan-Septentrion War. The line was constructed using forced labour from prisoners-of-war captured in Maverica and Innominada. This railway was later controlled by Hallian forces operating out of Themiclesia and served a similar function in the subsequent invasion of Menghe via Dzhungestan, and under this administration its capacity was enlarged significantly. At end of the war, the portion of the line within Themiclesia was ceded to that country. This railway remains operational as a freight and passenger railway to a number of small towns in the Themiclesian desert but terminates in Sn′ênk and no longer extends into Dzhungestan. A memorial has been erected in Sn′ênk in memory of the prisoners who died building this railway.

In the 2010s, the Trans-Hemithea High-Speed Railway was planned to link Dayashina, Menghe, Dzhungestan, Themiclesia, and Nukkumaa. This development was envisioned as an econmical alternative to air travel and freight that is faster than ocean transport between the states, which takes a less direct route. In design it is capable of a top speed of 300 km/h. The THHSR network is jointly operated by all parties involved and has been considered a remarkable success in political terms. It has uniform signal systems and track and loading gauge, this being enabled by congruences between the high-speed railways of Dayashina, Menghe, and Themiclesia, and dedicated customs offices permit non-stop service between origin and destination.

Maverica

Themiclesia is connected to Maverica by the Trans-Hemithean Railway, which opened in 1952 and connected further to Menghe. This line was forced to close down in 1959 in view of disquiet in Maverica that eventually led to the establishment of a Communist administration in 1960. Themiclesia removed railway infrastructure over several kilometer for fear of its utility to a hypothetical Maverican invasion. This line was reopened tentatively for freight transport in the late 80s, though trains were unable to pass without stops at the border.

Travelling direction

Most Themiclesian railway lines distinguish between "hither" (各, karāks) and "thither" (戉, mngwāts) travelling directions, which are usually equivalent to "up" and "down" trains on some other networks. During the era of private railroading, this terminology was usually applied relative to the locomotive's depot, such that journeys from the depot would be followed by the opposite journey back towards the depot. After consolidation, which permitted locomotives and trains to be maintained or assembled at more than one place, this distinction evolved to reflect the place of the railroad's headquarters, where travel towards it was considered hither. For National & Maritime, trains travelling towards Kien-k'ang were hither trains, while for Themiclesian Northwestern, those bound for Rak were hither. Currently, trains bound for Kien-k'ang are considered hither by National Rail, while those travelling away from it are thither.

Railways which are not on the inter-city network are more idiosyncratic in their nomenclature. Trains on forest and mine railways are often distinguished between trains into or out of the forest or mine.

Rolling stock

History

The first passenger train in Themiclesia, serving the route between Sngrak and Ped from 1836, offered only one class of service to the public—third class—but provided superior accommodations for the directors of the railway. From the 1840s, a three-class system modelled after Casaterran railways was introduced. Third-class coaches typically were open wagons fitted with benches, while second-class ones possessed glazed windows and upholstered seats. Early coaches were laid out in an open style, but soon compartment coaches became the norm for all classes under Anglian influence in the 1840s. Two-axle coaches were universal until bogie coaches, which permitted easier turning, appeared around 1852. In 1868, the Railways Act mandated that all rolling stock meant for passengers must be roofed.

Prior to the public operator's entry in 1892, there was no statutory standard for operators to classify their rolling stock in any particular way, though out of necessity most operators eventually developed systems that were more or less harmonized with each other, to enable throug running and joint operations. At the onset of the Pan-Septentrion War, all rolling stock was put on notice for commandeer and assigned a classification according to the Temporary Nomenclature issued in 1938; though so named, all Themiclesian operators continue to use it to this day.

Out of a desire for economy and interchangeability, the public operator National Rail had a policy of building standardized coaches for operation on all its lines, starting with wood-steel composite Series 2 (S2) in 1907; existing stock taken over from other operators were called S1 but are in reality not a standardized series. A standardized series usually shared the underframe and bogies and had similar external bodies, varying in internal layout. Series 3 was a short-lived experimental series, and Series 4 was made from 1920 onwards utilizing all-steel construction and 72' carriage length. S5 appeared in 1931 and was in effect a refinement of the all-steel S4; it remained in production until 1957, when the streamlined and air-conditioned S6 entered production.

First

- First (F) first appeared on Themiclesian railways in 1839. F coaches are usually in the compartment style, without a connecting corridor.

- First Open (FP) appeared in 1856 along with long-distance, through-running express services. An open design allowed sharing of lavatories and an on-board dining carriage, obviating the need for prolonged stops for lavatories or meals. Internal layouts vary but usually had bays containing two opposing rows of seats, with a central or side corridor. There were generally two or three seats in an each row in FO stock.

- Drawing Room (D) was introduced in 1875 as an alternative layout to the typical FO design at that time. Rather than rows of opposing seats, D coaches had rotating seats in an open, unobstructed layout.

- Drawing Room with Observation Platform (DB) was first used as a separate designation for a coach that had a specialized open platform at one end, meant to be at the end of the entire train and to allow passengers to have an unobstructed rear view. As carriages by default came to be built with vestibules in the 1880s, this style can be regarded as an evolution of the D body. It appeared on scenic routes starting from 1900.

- First with Drawing Room and Observation Platform (FDB), a further evolution, was operated by National Rail as a composite of the older FO layout and the more popular D layout, one being present on each end of the coach. Initially, passengers were allowed to specify in which section they wished to sit, but in 1901 the Drawing Room seats were no longer separate sold, being instead regarded as a secondary area for first class passengers to utilize. FDP was used as the final coach on most Reserved Trains during the pre-PSW era.

- First Sleeper (FS)

First/Second

- First Second Open (FSP), a composite coach used on trains where expected passenger volumes would not justify a complete first class carriage. The coach was divided into a first-class half and second-class half.

- First Second Dining (FSD), a composite coach used on long-distance trains which has separate sections for first and second class ticket holders.

Second

- Second (S), denoting a second-class coach in the compartment style. During the pre-regulation era, coach designs varied considerably in the Second range, with some railways using Second to denote what is a Third on other railways.

- Second Open (SP), denoting a second-class coach in the open style, with a central corridor separating seats. For 84' mainline coaches, there were typically 8 bays lengthwise, each sitting 8, providing 56 seats about a central corridor; for 60' branch coaches, the capacity was typically 48.

- Second Open AC (SPK) denoting second-class coach in open style, but with air conditioning. Introduced in 1957 on 84' coaches

- Second Recliner (SR) was experimentally introduced in 1932, utilizing recliners that could be alternately used as a normal chair during day and as a makeshift bed at night. The design purported to be a more comfortable alternative to normal seats on overnight trains, commonly attached to serve passengers who would not pay for a sleeper. To allow the chair to recline, all rows face the same direction, and at least post-PSW the chairs could be turned to turn to face the travelling direction.

The style was revived in 1947 onwards, but for long-distance day trains. At 84', capacity was typically 13 rows of 4 seats, with a central corridor, for a total of 52; at 72', a total of 48 seats was normal. Post-war, the SR style gained favour over the SO style, eventually becoming the standard second class layout.

- Second Dining (SD), used on trains where there was no first class service.

Third

- Third (T), denoting a third-class coach. T coaches had no standardized design prior to the Railways Act of 1864, and many were not different from goods wagons outfitted with side benches. After the Act, T coaches were generally also built as compartment coaches to a specified minimum compartment size of 4'-8".

- Third Open (TP) denoting a third-class coach in open style. Capacity varied considerably between stock but was standardized at 100 seats in 10 bays of 10 seats each.

- Third Open Express (TPX) introduced in 1930 by National Rail, which started running an all-third monoclass Limited Express service. Due to the added costs of operating a service at Limited Express standards, capacity was maximized in TPX stock. At 72' length, each TPX coach accommodated 120 passengers, in 12 bays of 10 seats each; a central corridor divided each bay asymmetrically into 3-seat and 2-seat sides. For S/5.1 at 84', capacity peaked at 140 passengers, but in S/6 it was reduced to 120.

- Third Recliner (TPR) introduced in 1960 as an alternative to the TPX series. These usually sat 96 passengers in chairs that provided only a moderate degree of recline.

Freight service

Subways and light rail transit

Inter-city network

| Line | Hither end | Thither end | Length | Electrified | Cities served en route | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric (km) | Imperial | |||||

| Inland Main Line | Tsin | Rak | 406.3 | 251 mi 73 ch | Yes | Sin |

| Central Line | Tsin | Tenibh | 797.1 | 494 mi 27 ch | No | Lrêng, Ploi, Sn′i |

| Northwest Main Line | Tsin | T′ub | 526.7 | 326 mi 45 ch | Yes | Kengrakw, Mgraq |

| Skngrak Line | Tsin | Skngrak | 833.6 | 516 mi 77 ch | From Ped | Mgraq, Ped, L′in |

| Coastal Main Line | Tsin | Skngrak | 1109.8 | 688 mi 2 ch | No | Ngang, R′ad, Dzep |

| West Main Line | Rim | De | 784.8 | 486 mi 42 ch | To Ped | Tor, Ngang, Ped, De |

| Tor Line | Tsin | Tor | 235.6 | 146 mi 10 ch | No | |

| Prjin Main Line | Tsin | Qe-pa | 702.9 | 435 mi 70 ch | To Qe-pa | Rim, Te, Qe-pa |

| Eastern Line | Nek | Rak | 503.2 | 312 mi | No | K′an |

| P′an Line | Tsin | P′an | 1423.6 | 882 mi 55 ch | No | |

| Southeast Line | Rim | Stseng | 808.9 | 501 mi 43 ch | No | Stui, Nek |

| South Loop | Tsin | Nedrings | 514.6 | 319 mi 12 ch | No | Nek, Gob-kri |

| South Main Line | Tsin | Ngwang-tu | 362.0 | 224 mi 35 ch | Yes | Stui |

| North Transverse Line | Rak | Skngrak | 692.5 | 429 mi 21 ch | Yes | Sn′i, T′ub, L′in |

| T′ub Line | Rak | De | 434.6 | 269 mi 45 ch | No | Sn′i, Rap, T′ub |

| Central Transverse Line | Rak | Ngang | 449.9 | 278 mi 79 ch | Yes | Ploi, Mgraq |

| Qong Main Line | Rak | Qong | 218.8 | 135 mi 47 ch | Yes | |

| Tenibh Line | Rak | Skngrak | 693.2 | 429 mi 69 ch | No | Tenibh, Pê |

| Riparian Line | Rak | Kengrakw | 278.0 | 172 mi 30 ch | No | Lrêng |

| Sin Line | Sin | Lreng | 102.1 | 63 mi 26 ch | Yes | |

| Kengrakw Line | Kengrakw | Ploi | 113.6 | 70 mi 33 ch | Yes | |

| West Isthmus Line | Qe-pa | Sam | 494.4 | 306 mi 39 ch | No | |

| East Isthmus Line | Te | Belong | 307.3 | 190 mi 47 ch | No | |

| L′in Main Line | Rim | Mek | 793.5 | 491 mi 77 ch | No | Loi, Ngang, Tats, Ped, Hrip, De, Pê |

| Prabay Line | Qong | Prabay | 773.5 | 479 mi 45 ch | No | |

| Great Eastern Line | Rak | Sakarna | 2235.8 | 1386 mi 17 ch | To ′An | ′An |

| Great Northern Line | Qong | Tiba | 2336.5 | 1448 mi 43 ch | No | ′An, Apollonia |

| Ka-ra Line | Apollonia | Ka-ra | 303.9 | 188 mi 31 ch | No | |

| Southwest Line | Tsin | Nedrings | 281.8 | 174 mi 51 ch | No | Prit |

| Trans-Hemithean Railway | Rim | Doi | 341.1 | 211 mi 44 ch | No | Nedrings, Ngwang-tu |

| Total | 19518.6 | 12102 mi | ||||